Shining light: Alfredo Jaar brings politics and human rights to the table

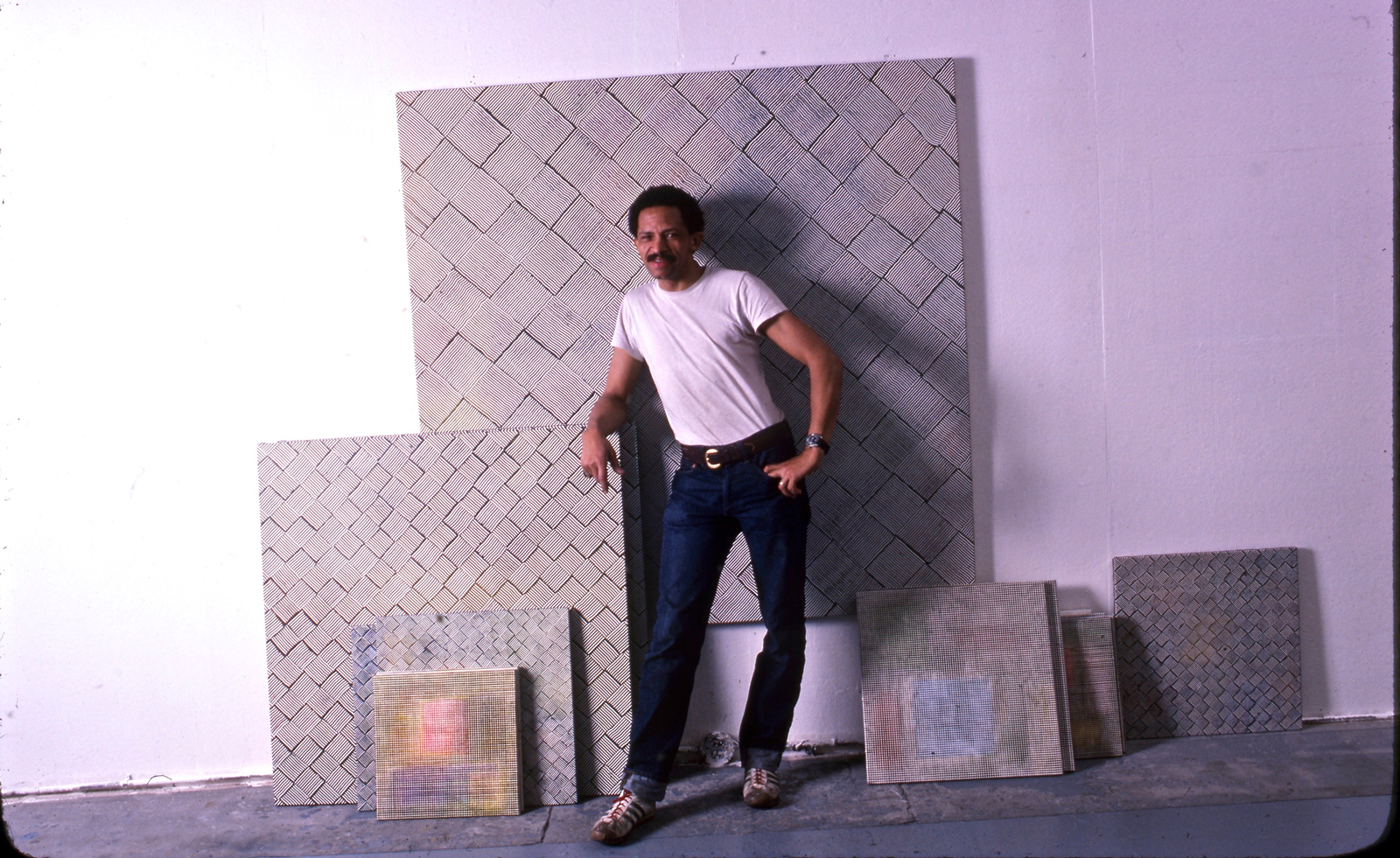

Alfredo Jaar does not describe himself as an artist, nor as a sculptor or filmmaker. Nonetheless, the Chilean has produced artworks, installations, films and photographs that focus on politics and human rights for over three decades. ‘I am an architect who makes art,’ he explains. ‘I studied architecture; I never received formal training in art. I need to understand before acting, which is how architects work. Context is everything.’

Jaar likes to say that his process is 99 per cent research and one per cent art, the majority of which takes place in his recently renovated studio in New York’s Chelsea. ‘This place is about understanding and researching. We don’t actually produce anything here,’ he explains. The space is simple – desks and artworks neatly aligned – and wrapped in white walls that ‘eliminate all the unnecessary clutter’ so that Jaar and his team can get to what he calls ‘the essence of things’.

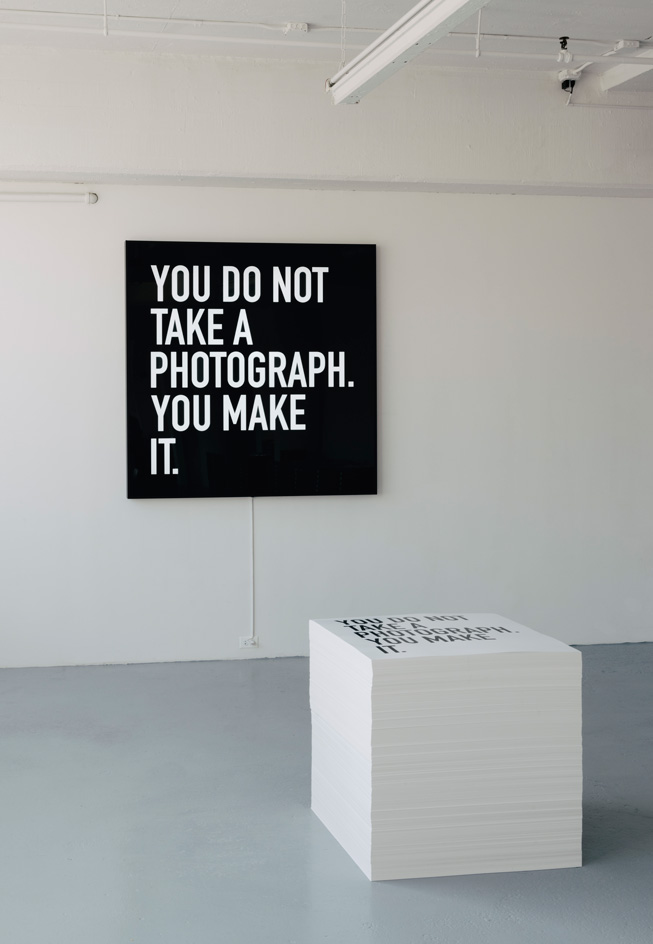

At the far end of the office, next to a window with a clear view of the Zaha Hadid-designed 520 West 28th apartments, a light box hanging on the wall reads, ‘You do not take a photograph. You make it.’ On the floor, a nearly identical image is reproduced on a stack of poster paper, which Jaar distributes freely. In an adjacent alcove, his Lament of the Images (2002) whirs gently as one light-box table is periodically raised and lowered above the other, casting geometric shadows.

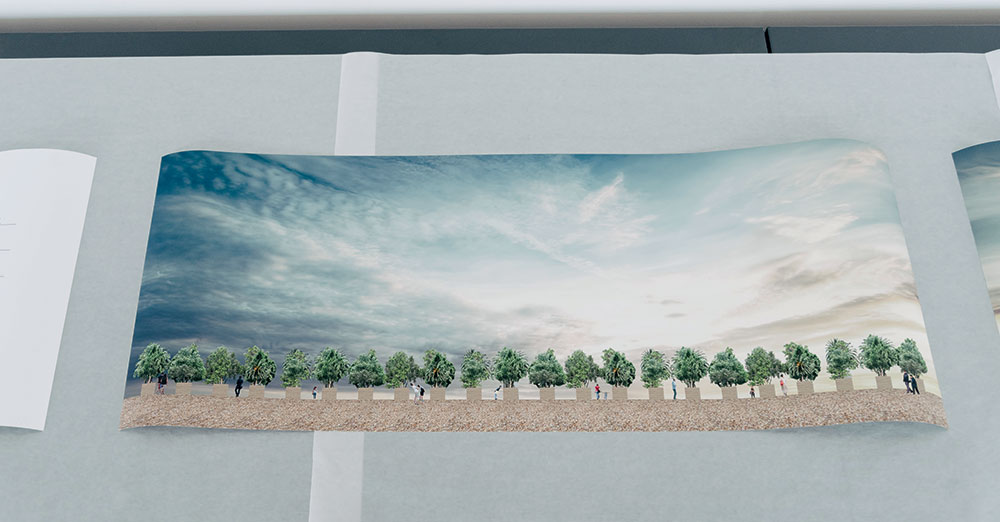

Work in progress for Jaar's latest piece, The Garden of Good and Evil, 2017, which will be on show at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, UK, from 14 October.

But if the architect-artist’s modus operandi — ‘I will not act in the world before understanding the world’ – ensures he spends ample time searching out and verifying facts in his studio, it also forces him out there, to bear witness. Jaar has travelled all over the world to see and record the worst crimes against humanity: genocide, wars, coups, torture. Then, he focuses on impressing the emotional gravity of these acts on a broad audience, one that has become increasingly desensitised to such horrors.

Jaar grew up around – or trying and failing to avoid – political tension and unrest. His family moved from Chile to Martinique when he was five. After a decade, they returned to Chile, just one year before the country’s infamous military coup that installed the brutal regime of General Augusto Pinochet in 1973. Jaar remained in Chile until 1982, when he moved to New York. Unsurprisingly, Jaar doesn’t identify strongly with any particular city or country. ‘I am not nationalistic,’ he says. ‘But this has made me more open to the world and has also influenced what I do as an artist. Nothing I make is the product of my imagination, I respond to real-life events.’

His first years in the United States led him to create one of his most famous works, This is Not America. Upon arriving stateside, Jaar was shocked to hear people say ‘God Bless America’ (meaning the United States) while referring to the rest of the continent as ‘South America’ and ‘Central America’. ‘I thought we were being erased from the map. For me, I am an American. Soy americano.

The Argentines, the Brazilians, somos todos americanos. Then you come here and find out that there was this idea of the “other Americas”. That’s bullshit.’ When he made the billboard animation in 1987, he intended to spark a semiotic dialogue around what America meant as a word. But, as happens with many of his works, the conversations surrounding This is Not America have moved far beyond Jaar’s initial intentions. In June 2016, it was shown in London’s Piccadilly Circus, and described as anti-Trump by The Guardian, an interpretation Jaar found amusing. ‘I never thought it would be anti-Trump,’ he laughs. ‘It is so fascinating how, as an artist, you lose control.’

A sense of control, and a perhaps begrudging acceptance of a lack thereof, factors heavily into Jaar’s work. ‘It’s hard, but at the same time it’s marvelous because [the work] gains in meaning, it becomes richer and more complex,’ he muses. Still, all of his art carefully choreographs how the piece is viewed.

It comprises a grove of 101 trees, arranged in a grid 50m long and 10m wide, in which are hidden nine cells that refer to the CIA’s secret interrogation prisons, or black sites.

This spatial consideration, a product of Jaar’s architectural training, can also perhaps be credited to his childhood fascination with magic, which he studied throughout his teenage years. ‘If you look at my works, they have a certain element of magic – the suspense, the lighting, the mise en scène, the construction of an environment that invites you to go somewhere that you don’t expect.’ This is especially evident in the trilogy of photography installations and a new piece that he is presenting at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, the open-air gallery on the 18th-century Bretton Hall estate in West Yorkshire, this autumn.

The Sound of Silence, his best known of these works (it has been shown 28 times since it was created in 2006), is typically installed as a mini-theatre devoted to an eight-minute film focused on one photograph. To avoid the frustrating predicament of having people walking in and out at the ‘wrong time’, Jaar devised a light system for the front of the theatre: a vertical green light indicates the film hasn’t started and one may enter, a horizontal red light means the film has started and one cannot go in. All of this is meticulously constructed to tell the story of the 1993 photo by South African photojournalist Kevin Carter that shows a tiny, emaciated girl in the Sudan crouching on the ground, a vulture behind her, watching predatorily. The scene is haunting, but in today’s relentless barrage of such images, Jaar doubles down on its impact. The video flashes between the photograph and text that describes the subsequent backlash Carter received after he won a Pulitzer Prize in 1994, which contributed to his suicide the same year. ‘An image is an incredibly complex construction. This piece was an attempt to say images are not so simple, things happen, this is how you create an image and this is what can happen,’ Jaar says.

Similarly, one must enter a room to view Shadows, usually walking down a long dark hallway where a small light-box displays three images by photographer Koen Wessing, detailing the execution of a farmer in front of his family during the 1978 Nicaraguan Civil War. Down another dark hallway, the viewer confronts a photo of the man’s daughters reacting to the execution. ‘It is the most extraordinary image of human suffering,’ says Jaar. ‘It’s like a dance of death, you can feel the pain in their movement.’ After two minutes, the background fades to black and slowly the women fade to white, a shade so bright that it lingers in your vision for ten to 15 minutes after.

Also shown is A Hundred Times Nguyen (1994), a photo installation from Jaar’s trip in 1991 to a Hong Kong detention centre housing refugees from the Vietnam War. A little girl, Nguyen Thi Thuy, became attached to Jaar during his visit and he photographed her several times at five-second intervals. When he looked at a sequence of four images later, he was captivated by how her expression changed slightly in each one. He labelled the images A, B, C and D, and then proceeded to reorder them in all of their 24 possible permutations. He then repeated the original A, B, C, D to create 100 total images. The repetition circumvents our natural inclination to view a photo for several seconds, maybe a minute, and then move on. Instead, we are forced to encounter the images time and again, fully absorbing Nguyen’s expression and getting to know her on some level.

I Can't Go On, I'll Go On, 2016, based on a quote by Samuel Beckett, on display in Jaar’s studio.

Jaar’s newest work, commissioned by Yorkshire Sculpture Park, eschews images and photographs entirely. The Garden of Good and Evil addresses the existence of ‘black sites’, secret interrogation prisons run by the CIA. Jaar had been toying with the idea of what cells would look like in these sites for some time, but struggled with how he would present the information. He began with recreating his version of the cells. ‘It was too direct. It was like a technical demonstration of something that exists, but I was still looking for the poetry,’ says Jaar. ‘The most interesting art walks this fine line between information and poetry.’ But, while he was touring the sculpture park in advance of the exhibition and admiring the sculptures and landscape, inspiration struck. Taking advantage of the park’s 500-acre space, he will hide nine different permutations of the cells within a grove of 101 trees. The cells are invisible from the outside, so viewers have to go among the trees to discover them. Initially, the trees in The Garden of Good and Evil will be in planters so the work can be installed near Jaar’s other three pieces in the Underground Gallery, but ultimately, the trees and cells will be installed on site permanently.

In a cultural and social climate increasingly obsessed with images and the politics behind them, Jaar’s work is timely, if not prescient. ‘The world has become incredibly complex. There are so many things happening – how can we possibly care about all these things at the same time? There are problems in our countries, problems in our cities, personal issues and family issues, but for me there are still very important issues of humans rights.’ And yes, the atrocities available with a swipe on our smartphones could quickly expend our emotional capacities. But perhaps the only thing more damaging than looking at them more closely is looking the other way.

As originally featured in the November 2017 issue of Wallpaper* (W*224)

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Work in progress for Jaar’s latest piece, The Garden of Good and Evil, 2017

You Do Not Take a Photograph. You Make It, 2013, a work based on a quote by Ansel Adams, on display in Jaar’s studio

INFORMATION

‘Alfredo Jaar: The Garden of Good and Evil’ runs from 14 October – 8 April at Yorkshire Sculpture Park. For more information, visit the Yorkshire Sculpture Park website

ADDRESS

Yorkshire Sculpture Park

West Bretton

Wakefield WF4 4JX

-

The White House faced the wrecking ball. Are these federal buildings next?

The White House faced the wrecking ball. Are these federal buildings next?Architects and preservationists weigh in on five buildings to watch in 2026, from brutalist icons to the 'Sistine Chapel' of New Deal art

-

Georgia Kemball's jewellery has Dover Street Market's stamp of approval: discover it here

Georgia Kemball's jewellery has Dover Street Market's stamp of approval: discover it hereSelf-taught jeweller Georgia Kemball is inspired by fairytales for her whimsical jewellery

-

The best way to see Mount Fuji? Book a stay here

The best way to see Mount Fuji? Book a stay hereAt the western foothills of Mount Fuji, Gora Kadan’s second property translates imperial heritage into a deeply immersive, design-led retreat

-

Rolf Sachs’ largest exhibition to date, ‘Be-rühren’, is a playful study of touch

Rolf Sachs’ largest exhibition to date, ‘Be-rühren’, is a playful study of touchA collection of over 150 of Rolf Sachs’ works speaks to his preoccupation with transforming everyday objects to create art that is sensory – both emotionally and physically

-

Architect Erin Besler is reframing the American tradition of barn raising

Architect Erin Besler is reframing the American tradition of barn raisingAt Art Omi sculpture and architecture park, NY, Besler turns barn raising into an inclusive project that challenges conventional notions of architecture

-

What is recycling good for, asks Mika Rottenberg at Hauser & Wirth Menorca

What is recycling good for, asks Mika Rottenberg at Hauser & Wirth MenorcaUS-based artist Mika Rottenberg rethinks the possibilities of rubbish in a colourful exhibition, spanning films, drawings and eerily anthropomorphic lamps

-

San Francisco’s controversial monument, the Vaillancourt Fountain, could be facing demolition

San Francisco’s controversial monument, the Vaillancourt Fountain, could be facing demolitionThe brutalist fountain is conspicuously absent from renders showing a redeveloped Embarcadero Plaza and people are unhappy about it, including the structure’s 95-year-old designer

-

See the fruits of Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely's creative and romantic union at Hauser & Wirth Somerset

See the fruits of Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely's creative and romantic union at Hauser & Wirth SomersetAn intimate exhibition at Hauser & Wirth Somerset explores three decades of a creative partnership

-

Technology, art and sculptures of fog: LUMA Arles kicks off the 2025/26 season

Technology, art and sculptures of fog: LUMA Arles kicks off the 2025/26 seasonThree different exhibitions at LUMA Arles, in France, delve into history in a celebration of all mediums; Amy Serafin went to explore

-

Inside Yinka Shonibare's first major show in Africa

Inside Yinka Shonibare's first major show in AfricaBritish-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare is showing 15 years of work, from quilts to sculptures, at Fondation H in Madagascar

-

Inside Jack Whitten’s contribution to American contemporary art

Inside Jack Whitten’s contribution to American contemporary artAs Jack Whitten exhibition ‘Speedchaser’ opens at Hauser & Wirth, London, and before a major retrospective at MoMA opens next year, we explore the American artist's impact