Allen Jones on pop sculpture, Kate Moss and almost becoming an American

Allen Jones, now 79, is possibly the most the controversial artist in the UK. He's certainly the most enduringly and consistently controversial. Jones has been divisive for 45 years, ever since he unveiled his notorious Hatstand, Table and Chair series of fantasy submissive ladies-as-furniture sculptures in 1970. And that is going some.

His detractors insist that his art objectifies women, his defenders that his art is about the objectification of women (amongst many other things). Few of either party would deny that he is amongst the most significant of British pop artists; and like his peers, an oddly conservative sort of radical, determined on keeping figurative art relevant after the onslaught of abstract expressionism and the rise of minimalism and conceptual art.

Jones, for all the notoriety of his art, is famously mild-mannered and more than pleasant company. Wallpaper* spoke to him at his studio on London’s Charterhouse Square, surrounded by his scantily clad and perfectly formed mannequins – one of whom is wearing a cabinet and is actually a functioning fridge – and maquettes of his large steel sculptures. (The studio and Jones’ apartment, where he lives with is wife Deirdre Morrow, is in a former hat factory he bought along with Howard Hodgkin, Richard Wentworth and John Hoyland in the early 70s. He also has a studio in Oxfordshire, designed by the architect Piers Gough, splitting his time between the two.)

Jones has just delivered the works for a new show, 'Colour Matters', at London’s Marlborough Fine Art gallery. The show includes wavy Perspex columns which contain actual items of clothing – high heels, bikinis and the like – and are topped with odd, abstracted acrylic heads as well as curving timber totems painted in high-gloss paint and the closest Jones get to actual abstraction.

He also returns to Kate Moss, one of the few subjects to actually sit for Jones and the subject of his already iconic 2013 photograph Body Armour. The portrait has Moss encased in a dazzling gold flake body cast – made by Jones for an unrealised film project in 1978.

Last year’s retrospective at the Royal Academy has spurred a late-career burst of activity and Jones shows no signs of slowing down.

Wallpaper*: Do you do different things in the two studios, think differently?

Allen Jones: Well, I like to say that I think in town. I’m trying to think whether I have actually conceived any works in Oxfordshire but I can’t. Essentially, I have the city around me here. I feel more comfortable in the city. But in some ways I don’t think about it that much. Sometimes if I have been working all day in the studio down there I walk out of the door and I’m amazed that there are fields.

Has your fundamental ambition remained the same over the years? And how much have you been affected by what has gone on?

I am totally influenced by the contemporary argument in a way. I like seeing work that is stylistically on the other side of the planet to me because then I can enjoy looking at it and feed off it.

I thought I would become an American in the mid-60s and I had a green card and all that. And now I look back at that period and realise that all the artists that I had a dialogue were non-figurative – people like Dan Flavin and Ad Reinhardt, who was a real mentor to me. It helps to be a visitor, to say 'can I come and see you?'. And the artists on the West Coast, they were so involved in process, that was really exciting. But I think the thing that changes is not what you do but how you do it. I’m locked into the figure.

You don’t have people to come and sit for you?

No, the last person to do that was Kate Moss. I very rarely do commissions. It’s not what interests me. I’m not interested in recording someone's likeness really. We go to Sadler’s Wells quite a lot. I have a good visual memory and I look at at the way someone is standing.

But Kate Moss has been a continuing subject?

Yes, but I think that it has come to an end now. The way that I work is that you have a formal idea and you play with it until you run out of steam. I drew her and it produced a couple of ideas for paintings and a sculpture. And of course I took her photograph. Strangely, the photograph was the last thing I did.

And that has become an iconic image now.

Yes. Well suddenly I realised that I had this sculpture that I had done for a film that never got made in the 1970s. It was made as a prop but never exhibited.

You wrote the film?

Yes. It was about a girl who wanted to be a model and needed a portfolio and the perils of trying to get that done. Unfortunately, she changes into a man, which is a terrible disadvantage. So her boyfriend makes this body sculpture for her.

It very nearly got made. We got into casting and I have a letter from Raquel Welch very nicely saying that her career was going in a different direction and didn’t want the part.

Anyway, I had this prop. And I had a shot a girl in it before so I knew it looked good. And the thing was that Kate was visiting my world, I wasn’t visiting hers. So that was the rationale. And it produced a good image. And the power of Kate in combination with a metal flake body meant that it got all the attention.

There will be a steel Kate in the new show with a bust cast clear resin cast, which is hard to do. And a wooden Kate.

And do you try and work with the baggage of Kate – her Kateness – or do you just do your own thing?

Well, I see those very much as a special assignment, as a side project. The other person I painted recently was Darcey Bussell. It’s great to look at a body again and have an excuse to really look closely at a body.

And so you bounced between sculpture, paintings and the figures?

Yes, I have a show coming up in February, another show of paintings, and again to do with an image that I created for a film in the 1970s. This was a cult film called Maîtresse that has Gérard Depardieu in it. [Directed by the late Barbet Schroeder, the film sees a young Depardieu playing a thief who burgles the home of a professional dominatrix.]

I was asked by the American distributors to do a poster. So I’d had the painting in the cabinet for years. It was an illustration, my construct of a maîtresse and she has knocked over the letters that form the title. It was like a comfort blanket in a way and it was like the other ways one’s work could have gone and become very illustrative. She is on a stage and I was wondering what would it be like if I was standing behind the curtains looking at the same scene. So I did a picture of that, and then what happens if she bends down to pick up the letters. I did a suite of four silk screens. I work with the same thing, I suppose, but if you change the medium, it forces your pictorial invention.

At the moment I’m rather interested in getting off the canvas. I can see some possibilities with the acrylic sheeting and the business of using a three-dimensional surface that contains its own lighting. If you have a yellow surface and you light it with a blue light it is going to change the yellow – that’s the departure point. My problem is where the figure comes in. I’m trying to bend these colour phenomena to my usage

Once you'd tried sculpture, what made you move back to painting? What were the possibilities in painting that weren’t there in sculpture?

Well, I suppose I thought in the 60s one was trying to learn a new pictoral language for the figure and using commercial sources. And they became more volumetric. So the idea came to me that they might be redundant and you should just make sculptures. But once I had made the sculptures, I realised the things that you can do with paint, which you can’t do with sculpture. So I like to think that it in a way, they kind of organically flip flop back.

And the sculptures are more than the figure stepping out of the painting? There’s more to it than that?

The sculptors that I have really thought about in the 20th century are Calder and Miró. And in both of those artists you see colour liberated from the traditional static surface. It is the civilising effect of having those formal considerations which keeps the demonic, illustrative side in check.

You could have established a real factory system, churning out series of figures or paintings. You were never tempted to do that?

I never worked out how I could have someone help me paint. I do the same amount of paintings now that I did 40 years ago. And they are a real labour, paintings, but I like to just buy in the talent when I need it. I don’t like the idea of having to keep working to keep a factory busy.

John Hoyland, my buddy downstairs, used to really turn it out. But he had a very different idea; that time and life will edit the work, the market will edit. I just think its temperamentally what you like to do. Bridget Riley was the first person I knew who had assistants. But I never really understood how you could have an idea and have five or six people working for on it for you.

Are you being asked to do more things now?

Well, I’m being asked to do more shows, I guess because of the RA show. My wife said, 'if only this had happened 20 years ago.'

Pictured left: Allen Jones. Right: Green Shoes, 2015

Jones’ new work still focuses on the female form, but is arguably less abrasive than the earlier, controversial ’women-as-furniture’ series from the 1960s. Pictured: ’Colour Matters’ (installation shot)

Considered by some to be a pioneering feminist, and by others to objectify women through his sculptures. Either way, Jones is one of Britain’s most feted and successful pop artists. Pictured left: Let’s Dance, 2014–15. Right: Red Shoes, 2015

Kate Moss has been a frequent muse and subject for Jones throughout his career – although he says the Moss-phase is now over for good. Pictured: A Model Model (detail), 2014–15

’Colour Matters’ includes both hyper-real imitations of the female figure and abstract forms that merely hint towards an idea of womanhood. Pictured left: A Model Model, 2014–15. Right: Black Shoes, 2015

Jones’ paintings and sculptures are held in major modern art museums globally, as well as commanding sky-high prices at auction. Pictured left: Cover Story, 2015. Right: Blue Queen, 2015

Preferring to work in ’pop’ materials, like plastic, Perspex and spray paint, Jones’ new pieces remain linked to and inspired by the static mannequins of his earlier work. Pictured: Black Shoes (detail), 2015

Despite this, sexually charged fibreglass women are not the focus of the new exhibition: figurative, indefinite models of the female face are well represented. Pictured: Red Head, 2015

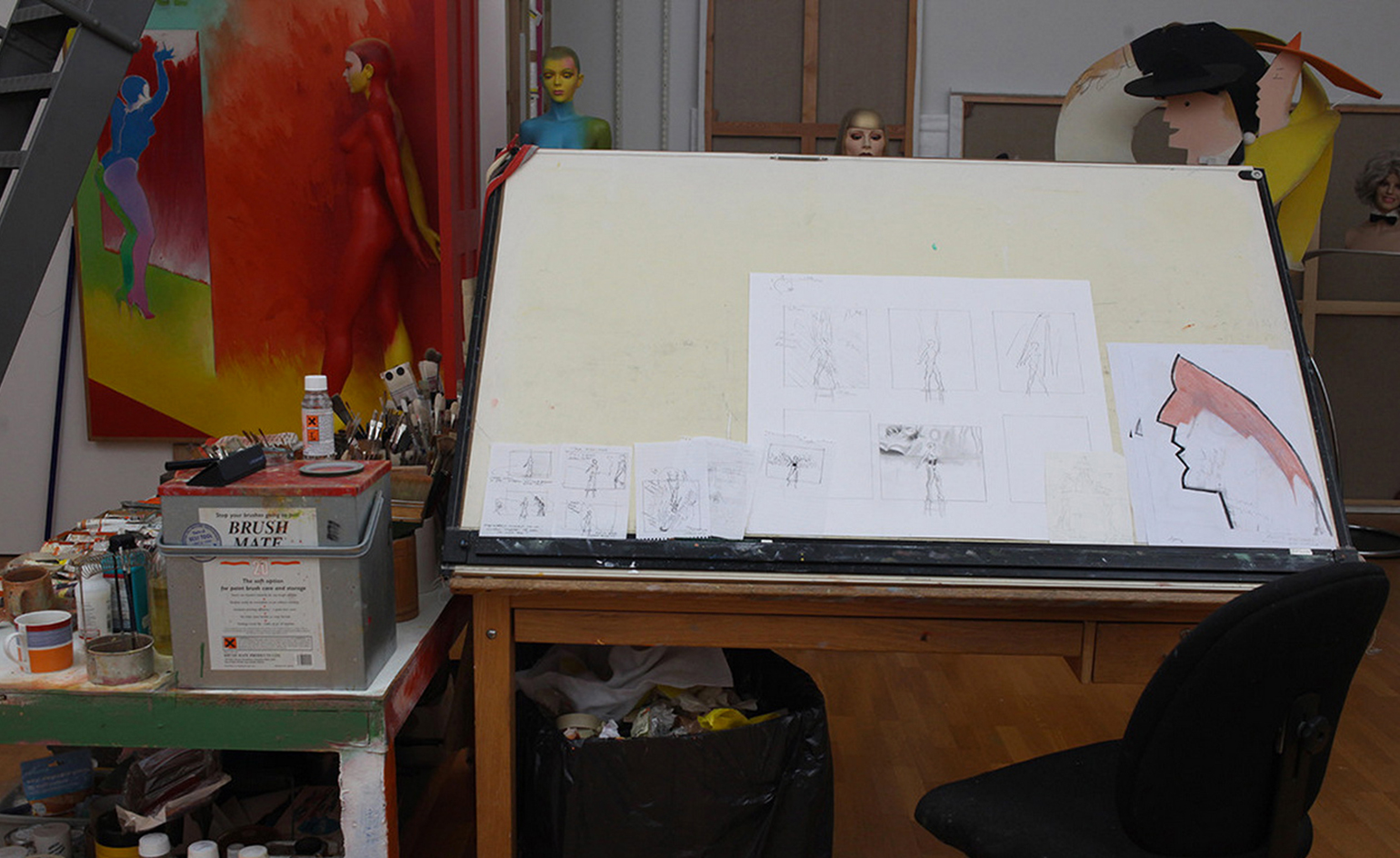

Jones admits he feels more at home in the city, but splits his time between his London studio (pictured) and his Oxfordshire retreat.

Located in the heart of London, Jones’ Clerkenwell studio (pictured) is filled with ideas, sketches and mannequins that double up as storage units.

Jones’ London studio

Although Jones is 79, there seems to be no indication of his retiring – or even slowing down – any time soon.

INFORMATION

’Allen Jones: Colour Matters’ is on view at Marlborough Fine Art, London, until 23 January 2016. For more information, visit Marlborough London’s website

Photography courtesy the artist and Marlborough Fine Art, London

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressing

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressingPart of our monthly Uprising series, Wallpaper* meets Benjamin Barron and Bror August Vestbø of All-In, the LVMH Prize-nominated label which bases its collections on a riotous cast of characters – real and imagined

By Orla Brennan

-

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationship

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationshipAnnouncing their marriage during Milan Design Week, the brands unveiled a collection, a car and a long term commitment

By Hugo Macdonald

-

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craft

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craftThe heritage furniture manufacturer is training a new generation of leather artisans

By Cristina Kiran Piotti

-

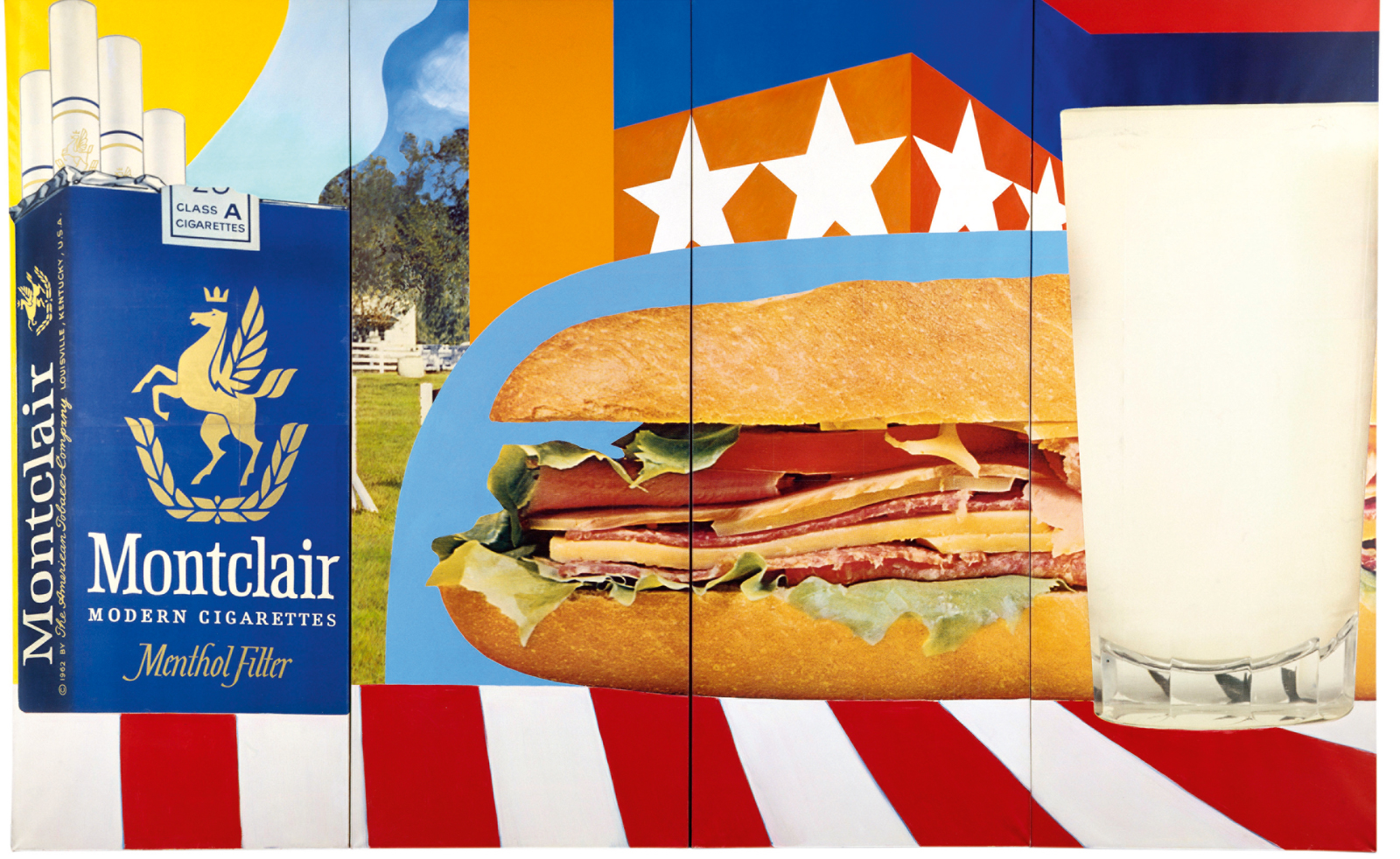

Tom Wesselmann’s enduring influence on pop art goes under the spotlight in Paris

Tom Wesselmann’s enduring influence on pop art goes under the spotlight in Paris‘Pop Forever, Tom Wesselmann &...’ is on view at Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris until 24 February 2025

By Ann Binlot

-

The dynamic duet of Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen

The dynamic duet of Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van BruggenRemembering Claes Oldenburg, who died aged 93 on 18 July 2022, we revisit our 2021 article celebrating his partnership with Coosje van Bruggen, as the duo’s final work together, Dropped Bouquet, was realised and exhibited at Pace New York’s ‘Claes & Coosje: A Duet’

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

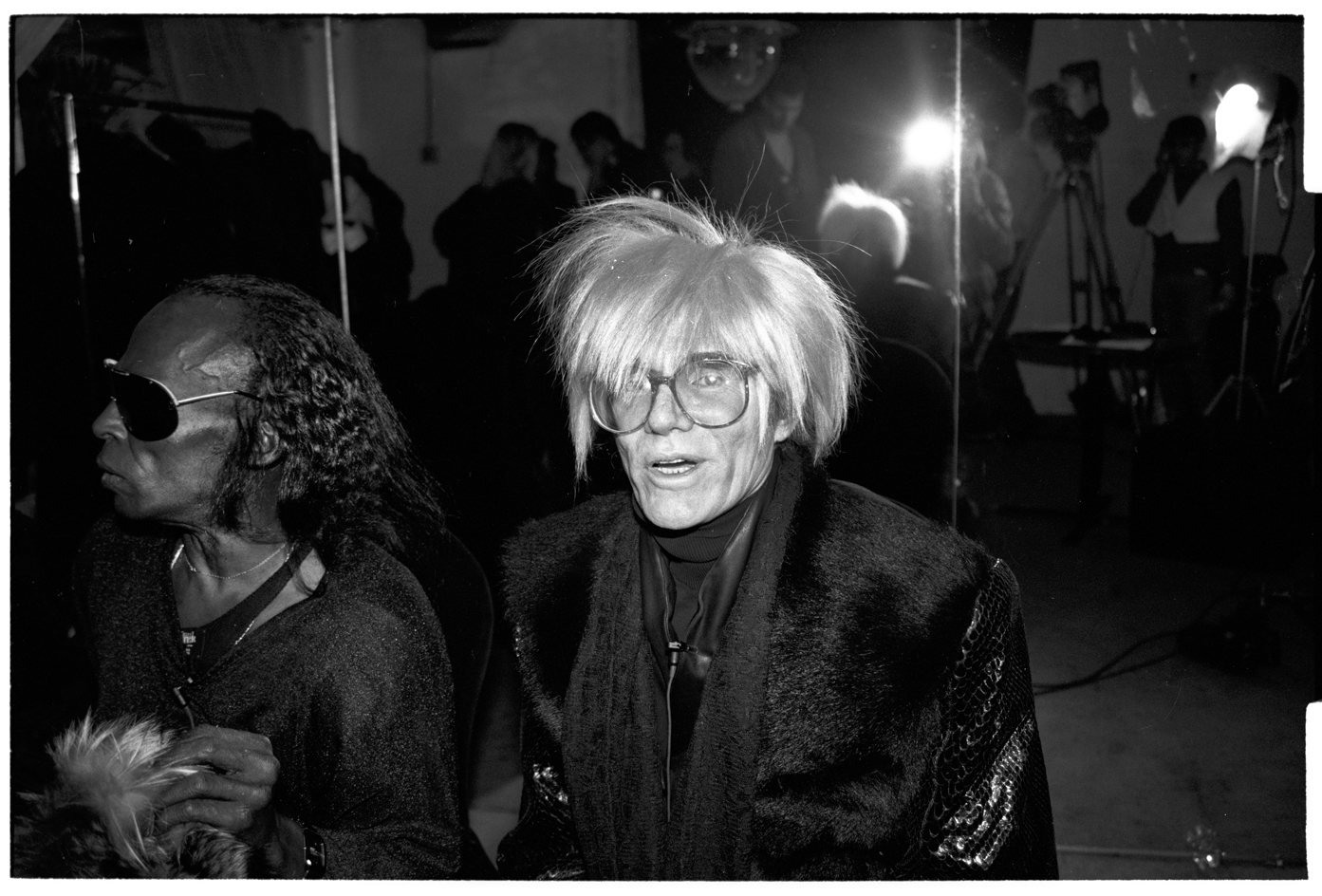

The Andy Warhol Diaries on Netflix reveals his enduring impact on contemporary art

The Andy Warhol Diaries on Netflix reveals his enduring impact on contemporary artWe review the new documentary, and showcase Warhol’s impact on modern culture through three artists: Deborah Kass, Jeff Koons and Glenn Ligon

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Inside pop art star Peter Blake's studio of curiosities

Inside pop art star Peter Blake's studio of curiositiesA new monograph and exhibition explore the fantastical life, work and studio of British pop art’s ‘godfather’ Peter Blake

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

James Rosenquist’s ‘fragments of reality’ ring alarm bells at Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac

James Rosenquist’s ‘fragments of reality’ ring alarm bells at Galerie Thaddaeus RopacBy Rooksana Hossenally

-

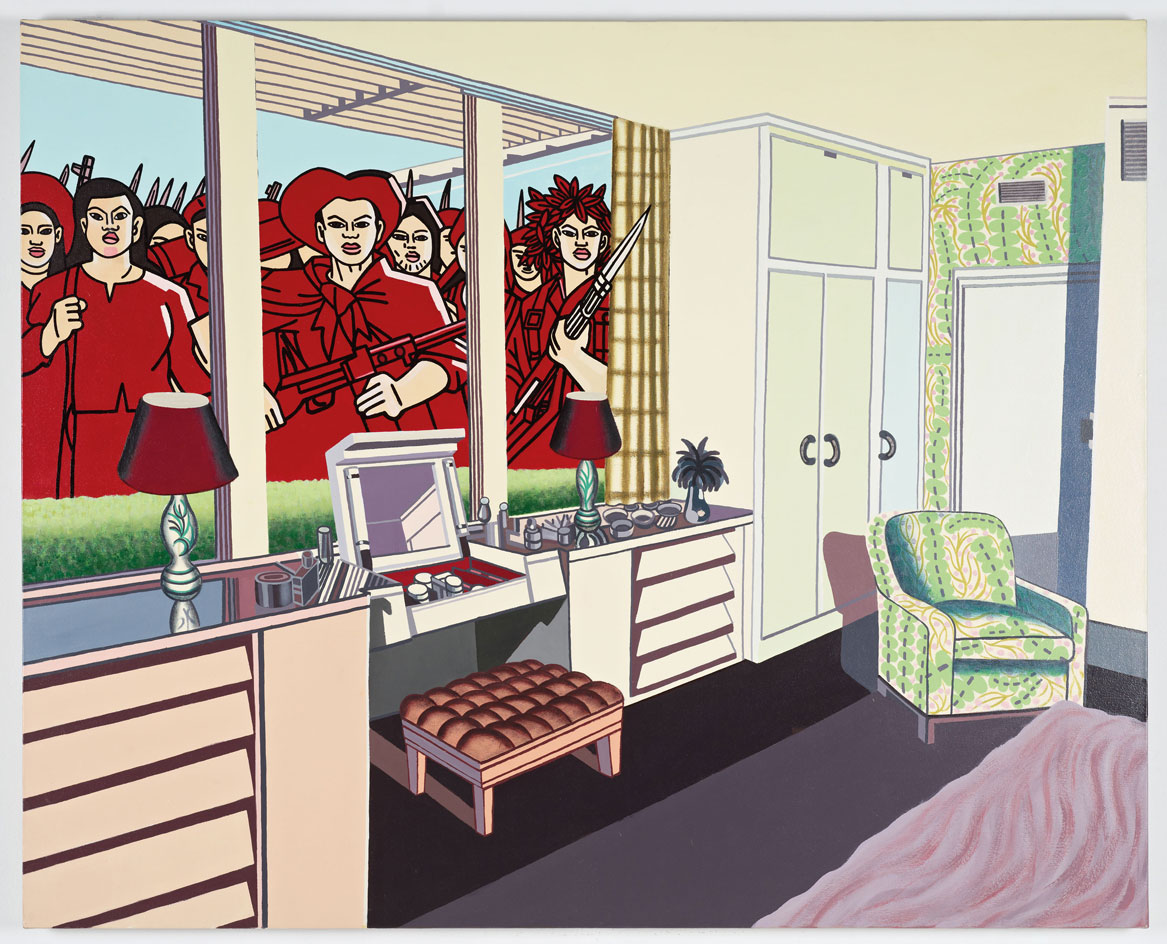

Pop as protest: Claudio Tozzi at Cecilia Brunson Projects, Bermondsey

Pop as protest: Claudio Tozzi at Cecilia Brunson Projects, BermondseyBy Florence Waters

-

Pop will eat itself: Tate Modern misses a trick with new global pop retrospective

Pop will eat itself: Tate Modern misses a trick with new global pop retrospectiveBy Ossian Ward

-

Post Pop: Saatchi Gallery’s latest show reflects on what happened after Warhol

Post Pop: Saatchi Gallery’s latest show reflects on what happened after WarholBy Ellen Himelfarb