Andreas Angelidakis blends antiquity, digital culture and urban modernity at Paris’ Espace Niemeyer

We speak to Greek artist Andreas Angelidakis as he unveils Center for the Critical Appreciation of Antiquity, a fantastical installation staged inside an Oscar Niemeyer-designed auditorium, commissioned by Audemars Piguet Contemporary

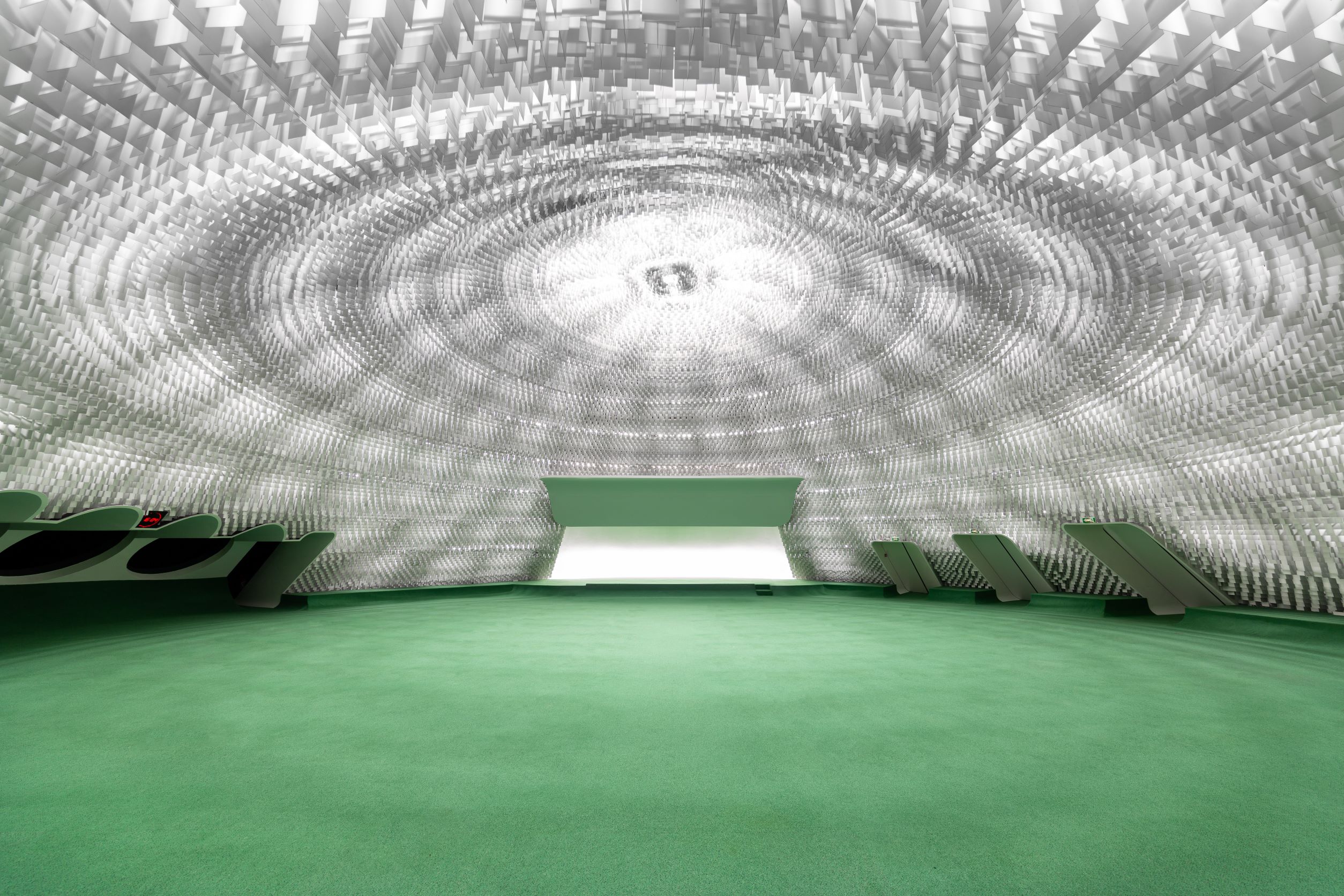

In 2003, Athenian artist Andreas Angelidakis found himself in Paris with Olivier Zahm, founder of Purple magazine. On Zahm’s suggestion, he visited the French Communist Party HQ building, designed by Brazilian modernist Oscar Niemeyer as a gift to the party. A trained architect himself, Angelidakis found it nothing less than ‘sensational and transcendent’. So this year when Denis Pernet, curator of the itinerant art programme Audemars Piguet Contemporary, invited him to create an installation in its auditorium, Angelidakis seized the opportunity. He decided to expand his series Soft Ruins, the modular exhibition furniture he conceived in the same year he’d first seen the building, to form ‘a disco monastery worksite’. An exemplar of how the Brazilians worked organic forms into modernism, the auditorium roof protrudes up through the premises’ front lawn as a dome inspired by a pregnant woman’s belly. Inside is a womb of grass-green carpet and diffused white light that will house the artist’s multimedia fantasy titled Center for the Critical Appreciation of Antiquity.

Studio Andreas Angelidakis.

Conversationally, Angelidakis is patient and precise. ‘This exhibition has a mystical geek vibe,’ he says when we meet in Athens in August, wearing leopard-print shorts and sitting on a sofa block digitally printed with an antique photo of a Greek column. His top-floor apartment beside the National Archaeological Museum is an Aladdin’s cave of tests. Over a 30-year career, Angelidakis has taken part in numerous biennials, panels with Hans Ulrich Obrist, booths at Art Basel, lectures at Columbia, and published a book titled Internet Suburbia. He’s been an architect, teacher, and curator. ‘I don’t see exhibitions as a display but an active ingredient to be played with.’ He remembers that in 2017, when he showed Soft Ruins at Documenta 14, security guards called him because visitors were moving pieces of the installation around: ‘I said, “Perfect!”’

In today’s version, his soft collapsed columns are accompanied by daybeds printed with archaeological pamphlets, scattered around a scaffold column rising through shadows of smoke and lights. On the auditorium screen, an infinity tunnel video extends the space like a portal. A metal container – resembling those used in shipping, building sites, and refugee camps – houses a ‘gift shop’ of Greek figurines and touristic objets.

Studio Andreas Angelidakis.

He calls this conglomerate ‘a system for a soft stylite home’, explaining that a stylite was a monk who sat in prayer atop a pillar (stylos) to be closer to god. He recounts how on top of the Temple of Olympian Zeus – the largest temple in ancient Athens – there used to be a hut, housing a stylite. It was removed in 1870, when the barely half-century-old modern Greek government pursued an archaeological policy that sought to eradicate almost 2,000 years of historical adaptations in a bid to produce an idealised Grecian aesthetic that would support a unified national identity in the aftermath of Ottoman rule.

Along with other elements of the temple’s social ecosystem (including coffee huts, trading, and diverse ceremonial practices) the hut was erased, not only from physical existence, but also from documentation. Nineteenth-century photographs of the ruin were tampered with as part of this national branding exercise that sought to portray Greece as a blanched monocultural fantasy, embodying the classical architectural ideals adored by the West.

Studio Andreas Angelidakis.

In the centre of Niemeyer’s auditorium, Angelidakis’ stylite pillar takes the form of a scaffold tower with his signature digital print of an Ionian column draped on one side, and a construction chute hung down the other. Athenian buildings have recently undergone much repurposing, to which the chute refers. Atop the pillar sits a metal container hut in signal yellow to match the chute.

And what of the monk who would be in the hut? ‘It could be any of us, doing our YouTube meditations on the sofa’ says the artist. Angelidakis enlists clubby elements, pointing out that people have gravitated towards both ancient temples and modern nightclubs in search of ritual highs. ‘You can be up on a column or on medical cannabis or anti-depressants, social media, coffee, wine – there are different ways of escaping reality.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Studio Andreas Angelidakis.

The artist remembers when the Temple of Olympian Zeus was cruising territory, and the installation’s video evokes classic gay club aesthetics that combine the idealised male forms of Grecian statues with the escapist positivity of disco. Angelidakis ordered 3D printed figurines online, with Ionian column-tops (‘the gayer column, based on a flower, with swirls’) positioned like hats, collars, skirts or pedestals on their white plastic bodies. ‘Ken the stylite,’ he jokes about these kitsch miniatures, which he filmed spinning on tiny podiums before layering them into the club portal video that beams out countertenor Klaus Nomi’s bittersweet cover of Donna Summer’s I Feel Love – as emblematic to club culture as columns are to architecture. ‘Nomi released that track when he was dying of Aids.’

Angelidakis’ archive diving is executed with intellectual expertise, but his motivations for pursuing it are more personal. ‘I’m also excavating myself. I’m always investigating why I’m so preoccupied with antiquity with my psychoanalyst.’ His father, a buildings engineer, used to make him visit archaeological sites when they hosted guests in Crete. He’s not immune to Greece’s pervasive nostalgia, nor to the queer community’s melancholic mythologies, both of which bandage wounds.

Curator Denis Pernet with Andreas Angelidakis.

By retrieving the stylite from history’s off-cuts pile and blending it with other suppressed cultural elements, Angelidakis brings aspects of the urban environment out of the shadows to be reintegrated – while you enjoy yourself! Lie on columns! Recall club highs! Espace Niemeyer is often referred to as retro-futuristic, an early-space-age vision of today. Angelidakis’ style is also retro-futuristic in its own way, quoting from the little utopias that 1970s and 80s clubs provided, including their historicist impulses. Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) is an ongoing reference, as is Superstudio. ‘I like mixing science fiction with antiquity.’

One of the booklets in the container ‘gift shop’ is titled Future Memory Club. He’s overlaid pages from antique archaeology pamphlets with his own fragmentary musings, featuring current keywords like Ukraine, monkeypox and micro-dosing. ‘I asked the Archaeological Society if I could re-print the original pages but they said no.’ Perhaps they were nervous about his approach. ‘People idolise ancient Greece as the birthplace of democracy but you had to be a wealthy male over 35 to be an Athenian citizen and vote.’

Angelidakis is interesting for many reasons – his progressive processing of Athenian conditions, his apartment’s funky bricolage furniture, the ‘queer brutalist’ island house he’s just built for himself, the intense relationship he shares with his fierce Pomeranian, Lupo. He was studying architecture at Columbia when it first abolished the use of hand tools, and asked students to design only on computers. ‘I was lucky to be part of that. The beginning of virtuality.’ Texture mapping, rendering, and video compositing produce his style, and he’s been ‘into digital archeology’ for 20 years’.

Studio Andreas Angelidakis.

It was 1965 when the PCF (Parti Communiste Français) commissioned Niemeyer to envision an inspiring headquarters from which to lead the leftist future they thought they’d see. A member of its Brazilian counterpart, the architect had just left Rio de Janeiro for Paris in self-imposed exile from his homeland’s right-wing government. Located on Place du Colonel Fabien, named after a French communist Second World War resistance hero, the headquarters opened in 1981, one of seven buildings in France by the architect, the last of which opened only this year at Château La Coste in Aix-en-Provence. Espace Niemeyer combines the formal clarity and lean lines of the broader modernist vision with free-form curves and expressive flourishes, resulting in a building of both restrained modesty and charismatic flair.

The Espace Niemeyer foundation was set up after the building was classified as a historical monument in 2007 to ensure its maintenance, raising funds by renting out its exquisitely designed environments. Arts organisations, media companies, and luxury brands have staged productions here, including Netflix and Prada. Curator Pernet’s interest is both aesthetic and philanthropic: paying to exhibit there contributes to its preservation and opens it to the public. ‘I wanted to bring Angelidakis’ Athenian perspective on cities and culture to a Paris audience,’ says Pernet. ‘The way he uses urbanism and digitality to comment on society means you don’t have to be an art world insider to understand his work.’ Angelidakis’ preoccupations with utopian fantasies and architectural ruins fit neatly with how we’ve come to look back on the visions of midcentury architects, including Niemeyer, and the dilapidated condition many of their buildings are in today.

Espace Niemeyer

That Audemars Piguet, the last-standing family-owned Swiss watch brand, has invited a deconstructivist Athenian contemporary artist to exhibit in Paris’ communist party HQ, designed by Niemeyer under protest exile, while contemporary European governments lean in increasingly right-wing directions, perfectly reflects the collapse of meaning in which culture is immersed now. This irreverent mashing together creates a sublimely entertaining presentation of decadence, performing Angelidakis’ theme of ruination and reflecting a post-ideological condition. ‘Crisis has been one of my subjects,’ says the artist. ‘Postmodernism was the beginning of our current notion of crisis as something recurring that’s part of our civilisation. In constant crisis, what’s wrong and right? You may as well go all the way and make a niche temple featuring a stylite monk in the Niemeyer dome.’

INFORMATION

The ‘Center for the Critical Appreciation of Antiquity,’ commissioned by Audemars Piguet Contemporary, runs from 11-30 October 2022, Espace Niemeyer. espace-niemeyer.fr; audemarspiguet.com

ADDRESS

2 Pl. du Colonel Fabien,

75019 Paris

Kasia Maciejowska is a writer and editor covering arts and culture. Her first book The House of Beauty and Culture (ICA, 2016) was about a radical London crafts collective, and she’s currently working on a monograph about Moroccan-French photographer Leila Alaoui (Skira, 2026). Consultancy clients include museums, galleries, design studios, and futures agencies. She also runs a creative career mentoring network for young refugee women

-

Year in Review: we’re always after innovations that interest us – here are ten of 2025’s best

Year in Review: we’re always after innovations that interest us – here are ten of 2025’s bestWe present ten pieces of tech that broke the mould in some way, from fresh takes on guitar design, new uses for old equipment and the world’s most retro smartwatch

-

Art and culture editor Hannah Silver's top ten interviews of 2025

Art and culture editor Hannah Silver's top ten interviews of 2025Glitching, coding and painting: 2025 has been a bumper year for art and culture. Here, Art and culture editor Hannah Silver selects her favourite moments

-

In Norway, remoteness becomes the new luxury

In Norway, remoteness becomes the new luxuryAcross islands and fjords, a new wave of design-led hideaways is elevating remoteness into a refined, elemental form of luxury

-

Edinburgh Art Festival 2023: from bog dancing to binge drinking

Edinburgh Art Festival 2023: from bog dancing to binge drinkingWhat to see at Edinburgh Art Festival 2023, championing women and queer artists, whether exploring Scottish bogland on film or casting hedonism in ceramic

-

Last chance to see: Devon Turnbull’s ‘HiFi Listening Room Dream No. 1’ at Lisson Gallery, London

Last chance to see: Devon Turnbull’s ‘HiFi Listening Room Dream No. 1’ at Lisson Gallery, LondonDevon Turnbull/OJAS’ handmade sound system matches minimalist aesthetics with a profound audiophonic experience – he tells us more

-

Hospital Rooms and Hauser & Wirth unite for a sensorial London exhibition and auction

Hospital Rooms and Hauser & Wirth unite for a sensorial London exhibition and auctionHospital Rooms and Hauser & Wirth are working together to raise money for arts and mental health charities

-

‘These Americans’: Will Vogt documents the USA’s rich at play

‘These Americans’: Will Vogt documents the USA’s rich at playWill Vogt’s photo book ‘These Americans’ is a deep dive into a world of privilege and excess, spanning 1969 to 1996

-

Brian Eno extends his ambient realms with these environment-altering sculptures

Brian Eno extends his ambient realms with these environment-altering sculpturesBrian Eno exhibits his new light box sculptures in London, alongside a unique speaker and iconic works by the late American light artist Dan Flavin

-

![The Bagri Foundation Commission: Asim Waqif, वेणु [Venu], 2023. Courtesy of the artist. Photo © Jo Underhill. exterior](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/QgFpUHisSVxoTW6BbkC6nS.jpg) Asim Waqif creates dense bamboo display at the Hayward in London

Asim Waqif creates dense bamboo display at the Hayward in LondonThe Bagri Foundation Commission, Asim Waqif’s वेणु [Venu], opens at the Hayward Gallery in London

-

Forrest Myers is off the wall at Catskill Art Space this summer

Forrest Myers is off the wall at Catskill Art Space this summerForrest ‘Frosty’ Myers makes his mark at Catskill Art Space, NY, celebrating 50 years of his monumental Manhattan installation, The Wall

-

Jim McDowell, aka ‘the Black Potter’, on the fire behind his face jugs

Jim McDowell, aka ‘the Black Potter’, on the fire behind his face jugsA former coal miner, Jim McDowell defied the odds to set up his workshop and keep a historic form of American pottery alive