Peripatetic Georgian artist Andro Wekua on work, war and wandering

Robbie Lawrence - Photography

Andro Wekua’s Berlin studio is located on a curve of the River Spree near the Tiergarten park. This used to be quite a backwater, but escalating property prices and proximity to the river have turned it into prime real estate turf. The studio is in the remains of an old red brick building, a surviving wing of a larger industrial complex, surrounded by seven construction sites with billboards for future co-working spaces and relocation invitations. As he shows me up to his second-floor atelier above a small printing works (and opposite the studio of British artist Angela Bulloch), Wekua explains he doesn’t expect to be here much longer – ‘the owner is here almost every day with potential buyers’ – but he doesn’t seem unduly concerned.

Wekua is aged just 40, but has been well known in the art world since his twenties. MoMA and the Saatchi Gallery own several of his pieces, he has a solo show currently running in Moscow, and two coming up in Berlin and Zurich. He may not be fully blue chip quite yet, but he’s not far off.

Other big-name artists in Berlin, such as Tomás Saraceno, Ai Weiwei and Olafur Eliasson, have factory-like studios with dozens of staff, but Wekua’s main atelier is almost empty, save for a number of modestly sized paintings in progress propped against the walls and a couple of tables covered in half-squeezed tubes of oil paint. The air is thick with the comforting aroma of turpentine. There are two chairs, which look like they came out of a skip, and a crate of bottled water. But no assistants scurrying around, no sign of hectic preparation for the shows – just the artist on his own.

Wekua explains, almost apologetically, that this isn’t his only studio, just the one he paints in at the moment, and that he has sent his two assistants home for the day. His sculptural works are all made at the Kunstbetrieb workshops in Basel and his films in another specialist studio in Zurich. He seems to be constantly on the move, dividing his time between these cities and, more recently, his country of birth, Georgia. ‘So far, I have had no problem living in different places,’ he says, ‘but I am starting to realise it would be good to decide so I am not scattered all over the world the whole time.’

Two recently completed works (left wall) hang in the studio alongside works in progress (facing) and a mode of an exhibition space (right).

Perhaps this state of permanent transit is why the studio space feels rather impersonal. The coloured oily tracks his fingers have smeared on the walls around each unfinished artwork are pretty much the only evidence he’s at work here. Yet the dozen or so paintings (portraits mostly) on display seem deeply personal, bursting with vibrant yellows, reds, pinks and blues.

‘I collect personal photos or ask friends for them – this is of someone I knew; this is me when I was young – but it doesn’t matter who they are, they may as well be strangers.’ Wekua then creates collages using the photos along with coloured paper, cut and torn. ‘An aspect of collage that I find fascinating,’ he says, ‘is that time is not necessarily linear. The various elements stem from different times and different places, but one can still depict them in an integrated way.’ When he is happy with the result, he sends the images off to a screen printer who scales them up and prints them on canvas or, in the case of the pictures here, sheet aluminium. The artist then works over the prints in oils, adding and subtracting and painting over until he is content. Wekua again emphasises his distance from the subjects, however intimate the paintings appear: ‘These are not portraits, they are figures,’ he explains. ‘There is a hardness about them, but it also interests me that there is a deeper narrative quality, too.’

Wekua’s powerful sculptures often feature life-like and life-sized androgynous adolescent figures. One piece for his Moscow show is of a teenage-looking figure with a huge black wolf nudging at her shoulder. Another, for Berlin, is of a figure standing in a pool, with water coming out of her various body parts like a fountain. His best known film, Never Sleep with a Strawberry in Your Mouth (2010), features yet more uncanny, android-like figures, this time played by humans, in a magical-realist domestic setting. Then there are the architectural models constructed partly from memory, of buildings from his former home town. What appears to connect them all is a strong sense of personal storytelling.

I ask him about the girl and the wolf, a theme that repeats itself in his sculptures. For many it is a motif dripping with narrative significance: Little Red Riding Hood, Studio Ghibli’s Princess Mononoke or one of the Stark children from Game of Thrones. The figure is both innocent and warrior-like. But Wekua is adamant that storytelling is not his intent: ‘They stand for something, but not someone. It is a sense of universal condition that moves me, that I express in one form or another. But that is not a story. If viewers want to see stories in my work, that is of course fine, but it would be great if they could grasp that condition as well.’ He does not go on to elucidate what that condition might be.

Works in progress, which began life as collages.

Tellingly perhaps, Wekua’s own backstory is always brought up in interpretations of his work. It is as if his refusal to admit to a narrative drives others to force one on him. He was born in 1977 in Sukhumi, a war-torn region of Georgia which is now known as the disputed territory of Abkhazia. In 1989, his father, a political activist, was killed by Abkhaz nationalists during the Sukhumi riots. His family fled the city and, aged 17, he was sent on exchange to an anthroposophic school in Basel. ‘The 1990s were bad times in Georgia. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, there was huge chaos. If there was a chance to get out and go somewhere else, it had to be taken. Nevertheless, it was still a good time for me, I had a lot of fun and was outside a lot. I did not want to leave.’ Switzerland was a culture shock: ‘It was depressing at the beginning and I was really alone.’

Wekua says he did not actively choose art as a profession: ‘I never knew what I wanted to be. But I drew a great deal as a child, so my father took me to a painter friend of his in Georgia who had a great studio, just like you imagine an old-fashioned atelier to be. I ended up going there twice a week. When he painted, I painted as well. It all sort of just came together.’

We talk about in-between spaces, like the location of his Berlin studio, that have allowed the creative scene to grow and evolve. They offer freedom to invent, to create something new. ‘It is the spaces in between that are important, but I can make my space anywhere because I carry everything I need with me.’ But what of the non-physical gaps? The spaces where emotions and memories and dreams exist? ‘Where I grew up in Georgia is very different now,’ he answers. ‘War, civil war and occupation have changed it massively, and much of what I knew in my childhood is not there anymore. Also, you imagine things differently to what they were, filling in the gaps with your imagination. My work is about closing these gaps.’

When he is working, the names for Wekua’s pieces come last of all. At the time of writing, two weeks before the first of his three shows, most of the new works are still nameless. By naming them he will be ascribing potential for meaning, which he seems reluctant to do: ‘Then there is no going back,’ he says. ‘Names are important, but then again some of my works don’t have a name even when they are done, even though I have tried to give them one.’

Wekua’s smeared fingermarks on the studio walls surround a work in progress.

His work tackles, if obliquely, family loss, war, displacement, culture shock and loneliness. His professed disinterest in his protagonists, his dismissal of the autobiographical, and his ultimate detachment from his creations may be self-protective, but it seems more likely that he does not want his work defined by his own circumstances.

Once his works are completed, Wekua says he detaches himself from them completely. ‘As soon as my work is exhibited somewhere, that is where the relationship stops,’ he explains. ‘The work is not an ambassador for my ideas, it becomes autonomous. When I see my work in an exhibition, I am just as much an observer as you are. If the work is not able to take on a life of its own, then it doesn’t leave the studio.’

As originally featured in the May 2018 issue of Wallpaper* (W*230)

INFORMATION

‘Dolphin in the Fountain’ is on view until 21 May at Moscow’s Garage Museum of Contemporary Art website. Further solo shows, both titled ‘Andro Wekua’, will be at Berlin’s Sprüth Magers, 27 April – 1 September, and at Kunsthalle Zürich, 9 June – 5 August

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationship

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationshipAnnouncing their marriage during Milan Design Week, the brands unveiled a collection, a car and a long term commitment

By Hugo Macdonald

-

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craft

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craftThe heritage furniture manufacturer is training a new generation of leather artisans

By Cristina Kiran Piotti

-

Wallpaper* checks in at The Eve Hotel Sydney: a lush urban escape

Wallpaper* checks in at The Eve Hotel Sydney: a lush urban escapeA new Sydney hotel makes a bold and biophilic addition to a buzzing neighbourhood that’s on the up

By Kee Foong

-

‘Humour is foundational’: artist Ella Kruglyanskaya on painting as a ‘highly questionable’ pursuit

‘Humour is foundational’: artist Ella Kruglyanskaya on painting as a ‘highly questionable’ pursuitElla Kruglyanskaya’s exhibition, ‘Shadows’ at Thomas Dane Gallery, is the first in a series of three this year, with openings in Basel and New York to follow

By Hannah Silver

-

Tasneem Sarkez's heady mix of kitsch, Arabic and Americana hits London

Tasneem Sarkez's heady mix of kitsch, Arabic and Americana hits LondonArtist Tasneem Sarkez draws on an eclectic range of references for her debut solo show, 'White-Knuckle' at Rose Easton

By Zoe Whitfield

-

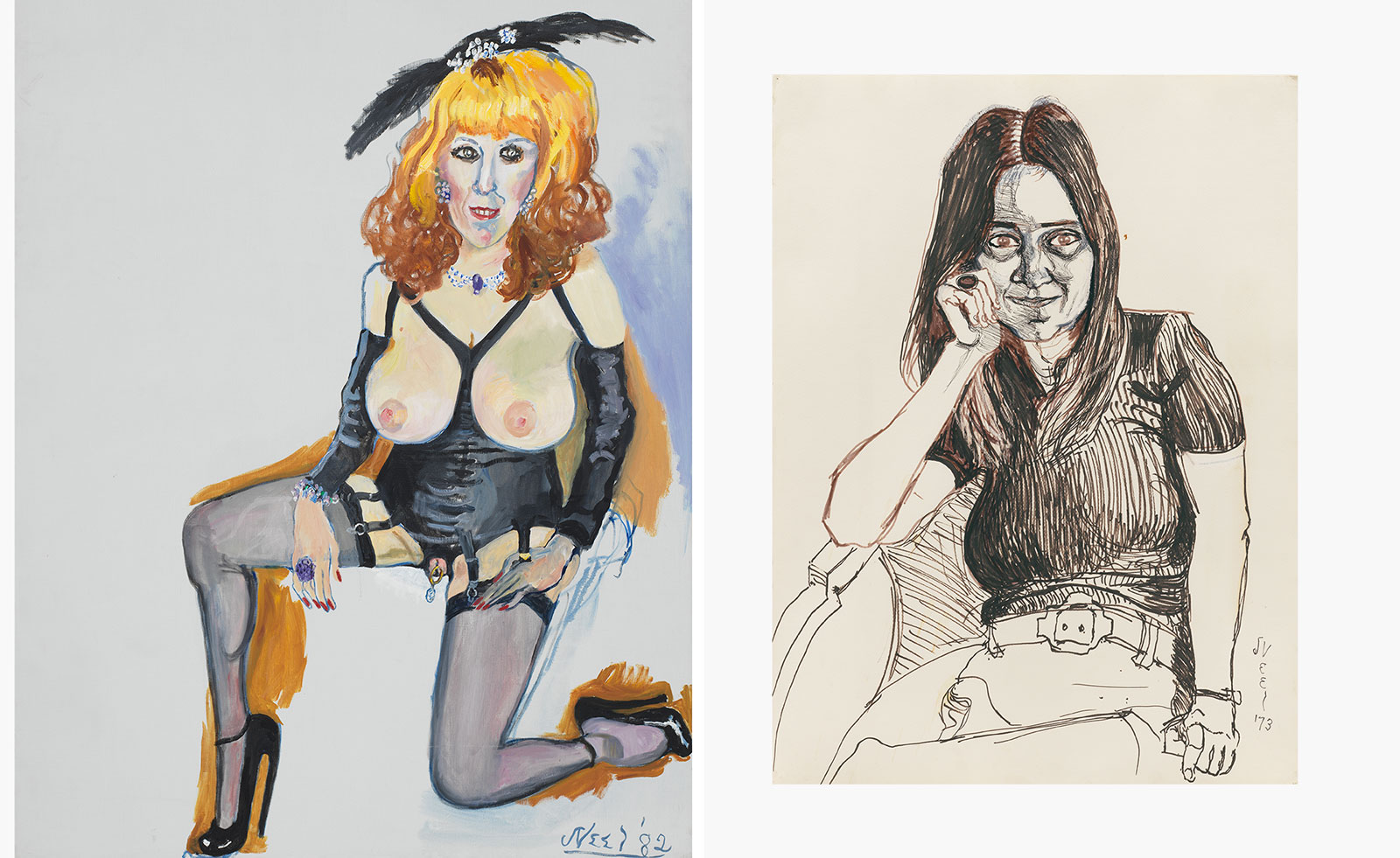

Alice Neel’s portraits celebrating the queer world are exhibited in London

Alice Neel’s portraits celebrating the queer world are exhibited in London‘At Home: Alice Neel in the Queer World’, curated by Hilton Als, opens at Victoria Miro, London

By Hannah Silver

-

‘You have to face death to feel alive’: Dark fairytales come to life in London exhibition

‘You have to face death to feel alive’: Dark fairytales come to life in London exhibitionDaniel Malarkey, the curator of ‘Last Night I Dreamt of Manderley’ at London’s Alison Jacques gallery, celebrates the fantastical

By Phin Jennings

-

Switzerland’s best art exhibitions to see in 2025

Switzerland’s best art exhibitions to see in 2025Art fans, here’s your bucket list of the standout exhibitions to see in Switzerland in 2025, exploring compelling themes and diverse media

By Simon Mills

-

Inside the distorted world of artist George Rouy

Inside the distorted world of artist George RouyFrequently drawing comparisons with Francis Bacon, painter George Rouy is gaining peer points for his use of classic techniques to distort the human form

By Hannah Silver

-

Love, melancholy and domesticity: Anna Calleja is a painter to watch

Love, melancholy and domesticity: Anna Calleja is a painter to watchAnna Calleja explores everyday themes in her exhibition, ‘One Fine Day in the Middle of the Night’, at Sim Smith, London

By Emily Steer

-

Out of office: what the Wallpaper* editors have been doing this week

Out of office: what the Wallpaper* editors have been doing this weekA snowy Swiss Alpine sleepover, a design book fest in Milan, and a night with Steve Coogan in London – our editors' out-of-hours adventures this week

By Bill Prince