The Anni Albers retrospective at Tate Modern anticipates 100 years of Bauhaus

‘Where do the creative spheres of the technician and the artist meet?’ asked Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius in 1926. For artist, teacher and textile pioneer Anni Albers, the meeting point was a weaving loom – a humble tool that she would transform into a vehicle of innovation.

Anticipating 100 years since the founding of the Bauhaus, Tate Modern is hosting Albers’ first major UK retrospective, following an extensive exhibition at the K20 museum in Düsseldorf. Tracing a production line of 350 studies, wall hangings, jewellery and prints, and reinforced by Albers’ seminal books, On Designing and On Weaving, the exhibition provides a rounded chronology of the methodology and research of perhaps the most influential textile designer of the 20th century.

The Bauhaus was a manifesto made flesh, a creative powerhouse disbanded by Nazis before it could reach full force. For Hitler, it was the Jewish threat incarnate; for those who attended, it promised a new, liberal mode of education. Having joined in 1922, Albers soon became intrinsic to the rationalist, functionalist Bauhaus, and the Bauhaus in turn became a work of living art.

Shortly after arriving as a student on the Weimar campus, Anni Fleischmann (as she was then known), married her teacher, Josef Albers, drawn by their mutual devotion to abstraction. The young couple relocated to the Dessau campus in 1926; Josef began his post as junior master and Anni began giving warmth to the often sterile architecture of modernism.

Anni Albers in her weaving studio at Black Mountain College, 1937

Although gender policy at the Bauhaus was supposedly egalitarian, women were still spurned from certain disciplines; Albers sacrificed painting (her first love) and fell into weaving by default. ‘The rule was, women were weavers,’ explains Torsten Blume, research associate at the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation. ‘Women were seen as soft and too weak for serious thinking. The strange thing is, weaving was the most intellectually challenging workshop at the Bauhaus.’

Albers reveled in the flexibility, complexity and unforgiving rigidity of the loom, refining her distinctive ‘pictorial weaves’ in the workshop she first described as ‘rather sissy’ but would come to lead. ‘Circumstances held me to threads and they won me over,’ she wrote, decades later.

In 1933, the Albers fled Germany to America, travelling to Mexico, Cuba, Chile and Peru. Anni became enthralled with ancient South American weaving techniques, tying historical ‘craft’ weaving with the vocabulary of modern art, then spinning both into architecture.

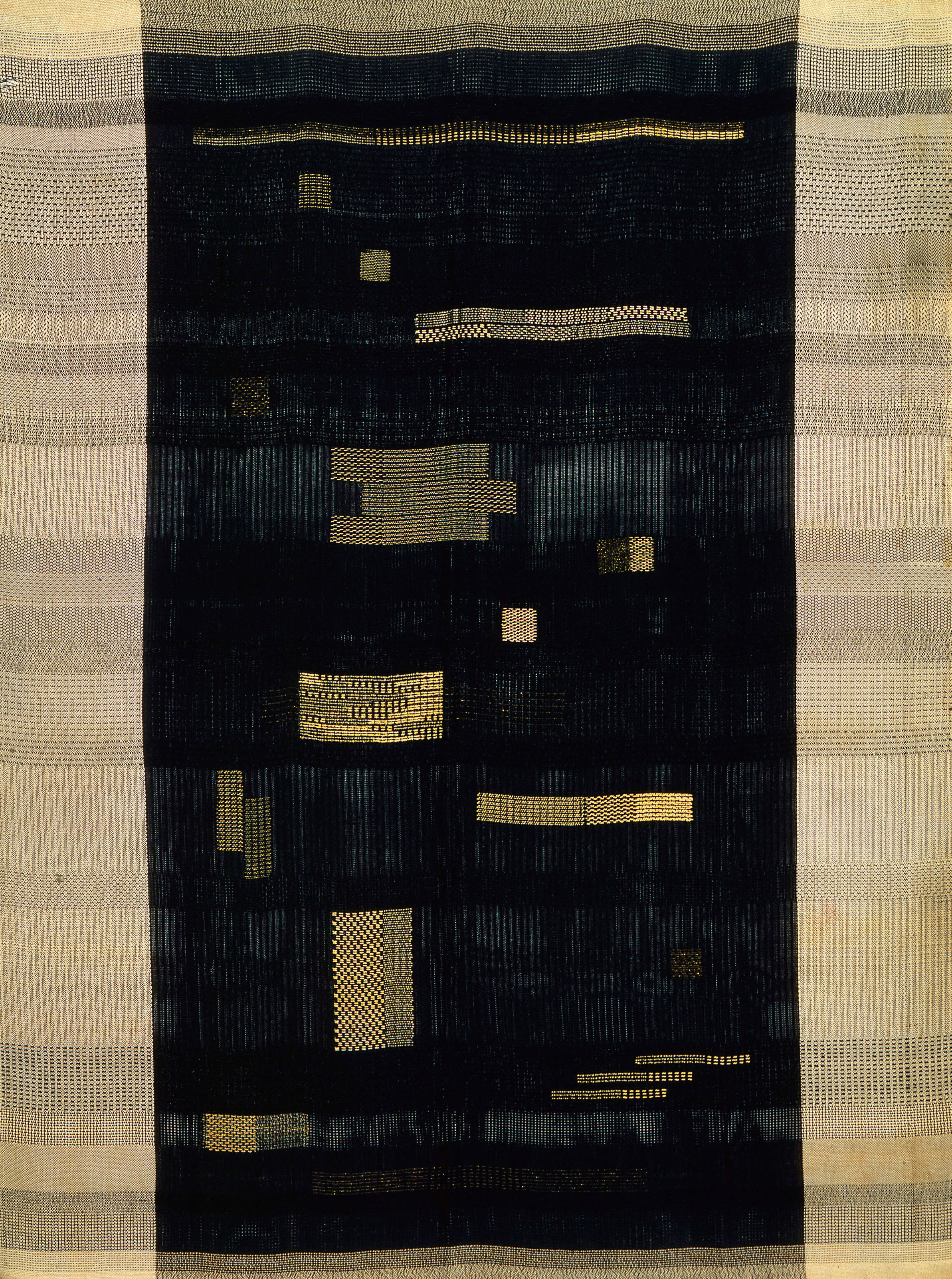

In her own words, Albers’ textiles ‘find a form for themselves... not to be walked on, only to be looked at.’ But her work did find function, as free-hanging room dividers and acoustic implements. Six Prayers, a meditative six-panel Holocaust memorial woven in cotton linen, raffia and stiff metal yarn, was an especially powerful example of an art form she revolutionised.

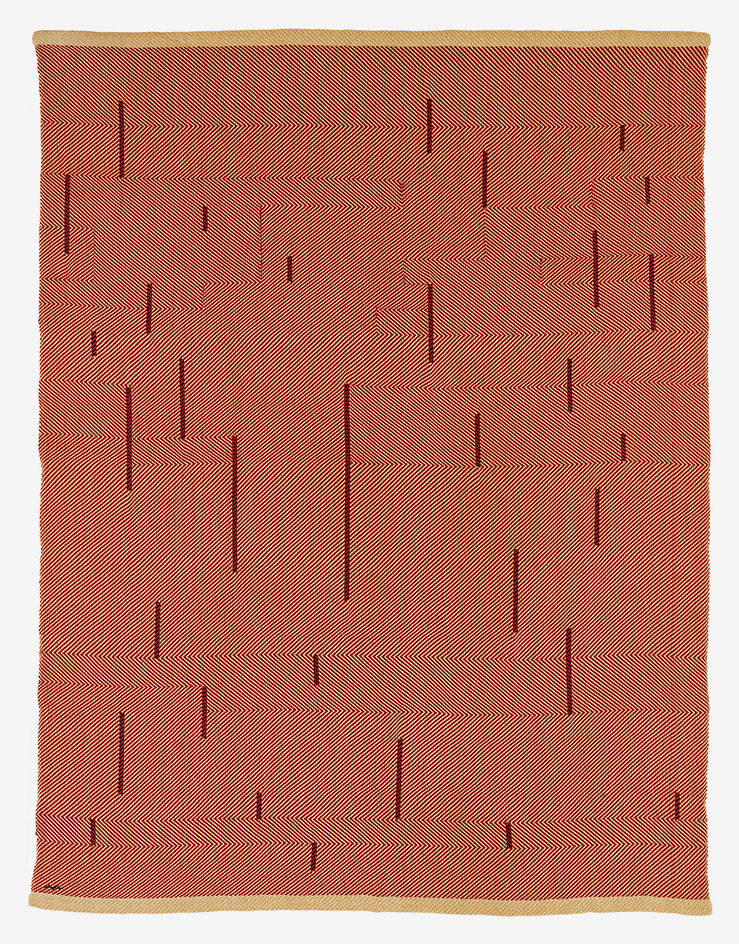

With Verticals, 1946, by Anni Albers, red cotton and linen. The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany CT. © 2018 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London. Photography: Tim Nighswander/Imaging4Art

Albers relentlessly toyed with materials including horsehair, silk, chenille, cotton, jute and even cellophane, which lent iridescence to her work. ‘She articulates the way handweaving can become a laboratory,’ says art historian Briony Fer, who curated the exhibition at Tate.

The artist’s looms are presented here as an extension of her body and weaving as a discipline demanding rhythm, foresight and sensitivity to material. ‘Being creative is not so much the desire to do something as the listening to that, which wants to be done: the dictation of the materials,’ Albers said.

Albers continues to influence a thread of contemporary creatives including fibre artist, Sheila Hicks – who studied under both Anni and Josef – and fashion designer Paul Smith, who is currently crafting a limited-edition line of Albers-infused knitwear.

The exhibition is not only a merited celebration of the artist’s work, but also an argument against the spurious division between art and craft. ‘Galleries and museums didn’t show textiles, that was always considered craft and not art. When it’s on paper it’s art,’ Albers remarked in 1984. Fatefully, it was only thanks to prints produced in her latter years that the artist ultimately gained the recognition her weaves were so long denied.

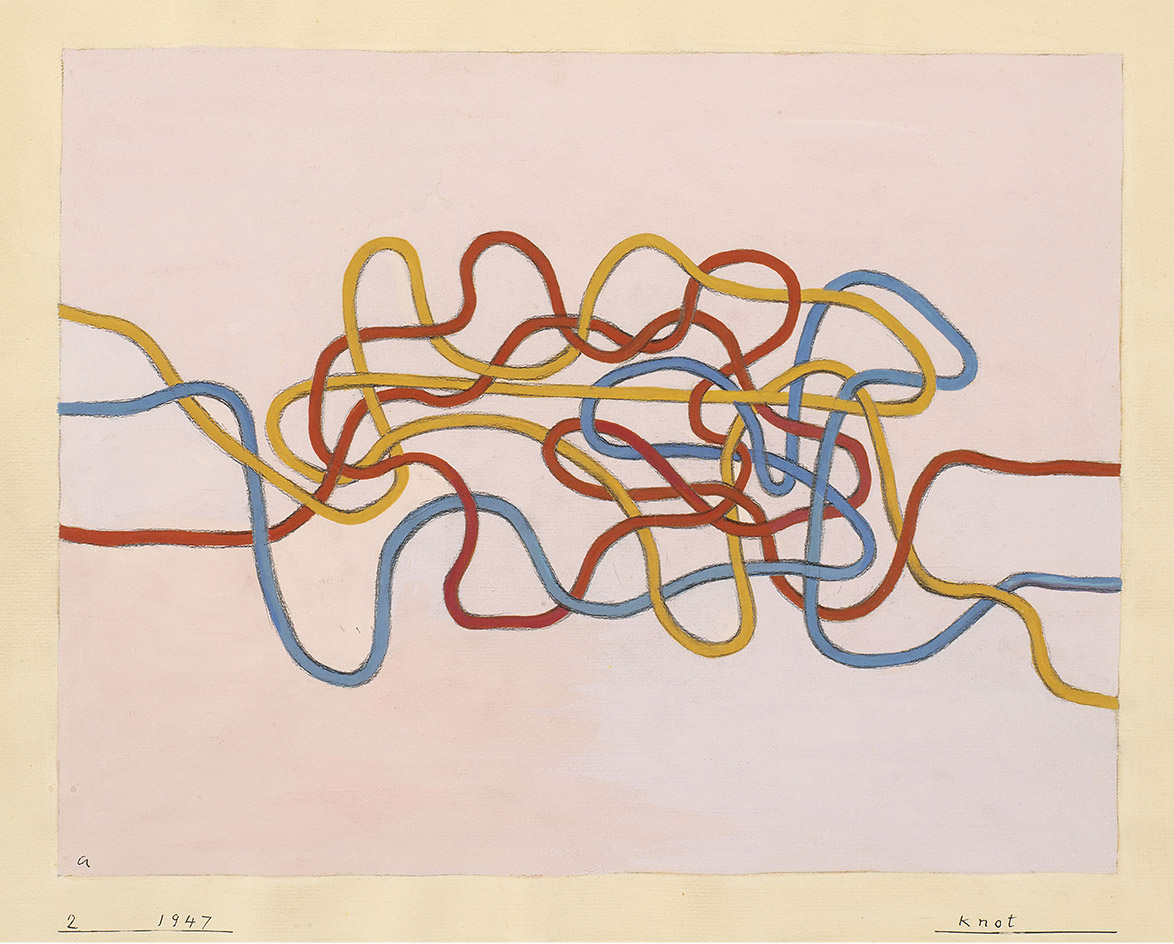

Knot, 1947, by Anni Albers, gouache on paper. The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany CT. © 2018 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London.

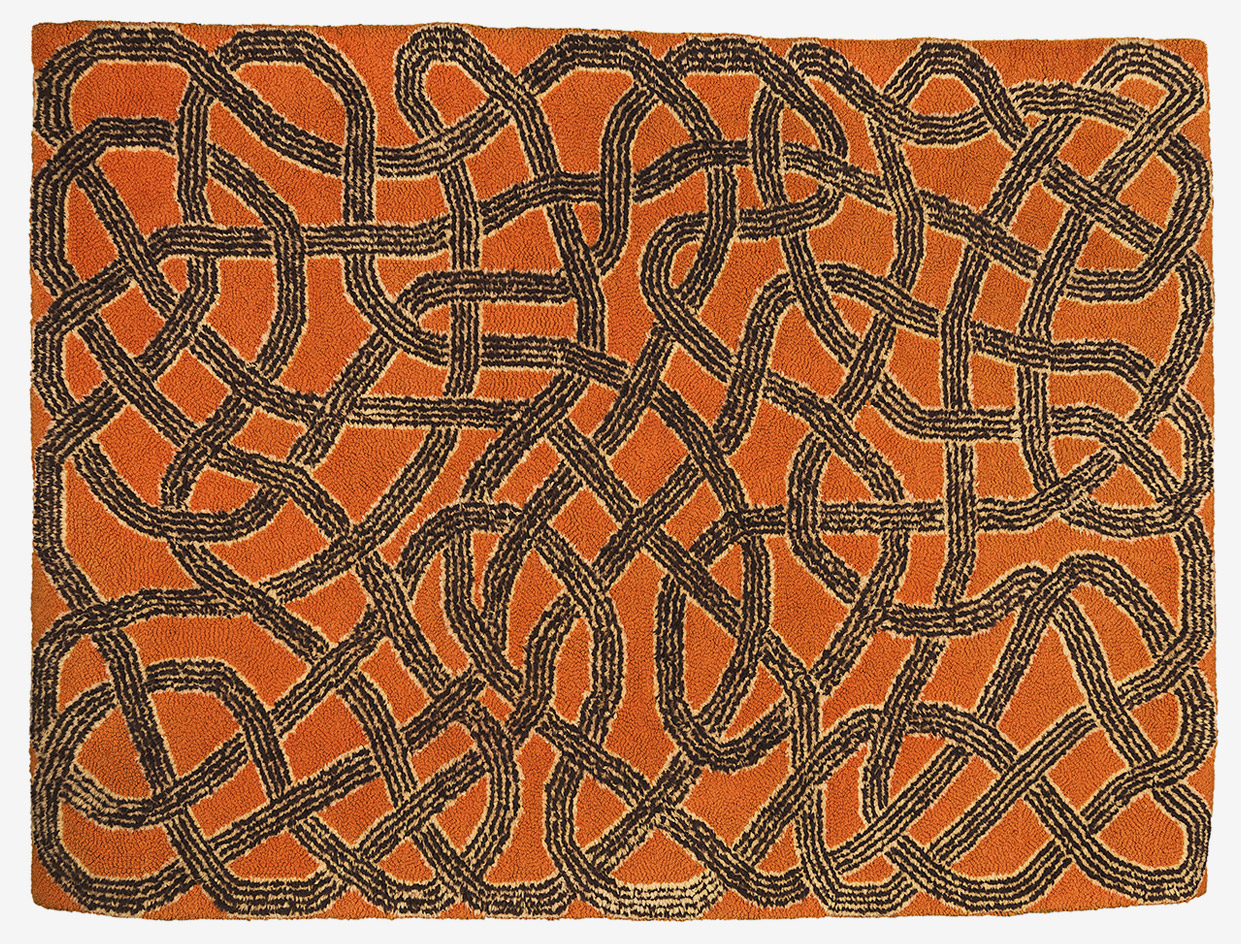

Ancient Writing, 1936, by Anni Albers, cotton and rayon. Courtesy of Smithsonian American Art Museum. Gift of John Young © 2018 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London

Six Prayers, 1966-67, by Anni Albers, cotton, linen, bast, silver, Lurex. Courtesy of The Jewish Museum, New York, Gift of the Albert A List Family, JM

Wall Hanging, 1926, by Anni Albers, mercerised cotton, silk. Courtesy of Museum of Modern Art, New York, gift of the designer. © 2018 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London

TR II, 1970 , by Anni Albers , lithograph . The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation, Bethany CT . © 2018 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London

Necklace, by Anni Albers, eye hooks and pearl beads on thread. Reconstruction of the original by Mary Emma Harris The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London

INFORMATION

‘Anni Albers’ is on view at Tate Modern from 11 October 2018 – 27 January 2019. Organised by Tate Modern and Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf. For more information, visit the Tate website

ADDRESS

Tate Modern

Bankside

London SE1 9TG

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Harriet Lloyd-Smith was the Arts Editor of Wallpaper*, responsible for the art pages across digital and print, including profiles, exhibition reviews, and contemporary art collaborations. She started at Wallpaper* in 2017 and has written for leading contemporary art publications, auction houses and arts charities, and lectured on review writing and art journalism. When she’s not writing about art, she’s making her own.

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss

-

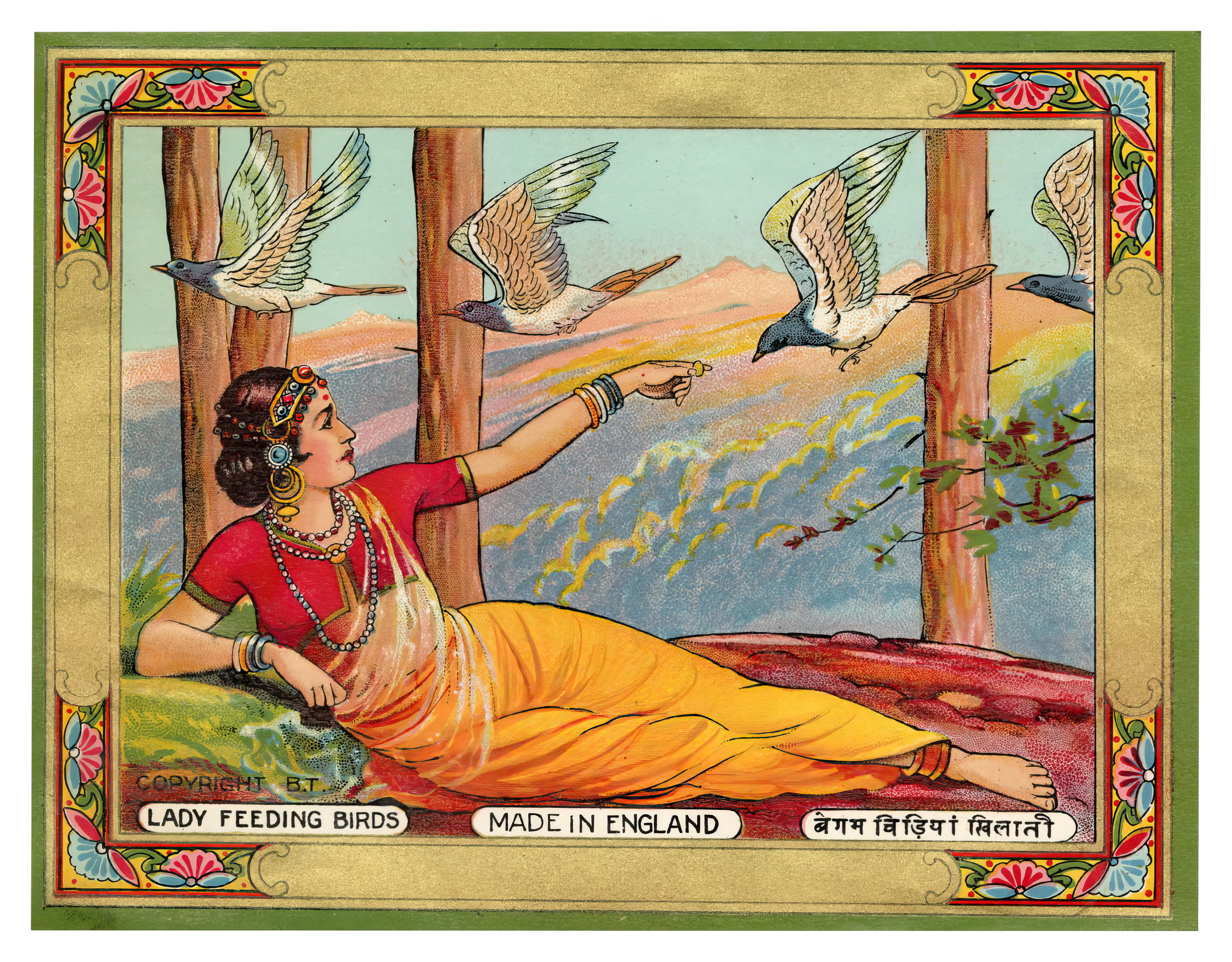

The art of the textile label: how British mill-made cloth sold itself to Indian buyers

The art of the textile label: how British mill-made cloth sold itself to Indian buyersAn exhibition of Indo-British textile labels at the Museum of Art & Photography (MAP) in Bengaluru is a journey through colonial desire and the design of mass persuasion

By Aastha D

-

Artist Qualeasha Wood explores the digital glitch to weave stories of the Black female experience

Artist Qualeasha Wood explores the digital glitch to weave stories of the Black female experienceIn ‘Malware’, her new London exhibition at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, the American artist’s tapestries, tuftings and videos delve into the world of internet malfunction

By Hannah Silver

-

Ed Atkins confronts death at Tate Britain

Ed Atkins confronts death at Tate BritainIn his new London exhibition, the artist prods at the limits of existence through digital and physical works, including a film starring Toby Jones

By Emily Steer

-

Tom Wesselmann’s 'Up Close' and the anatomy of desire

Tom Wesselmann’s 'Up Close' and the anatomy of desireIn a new exhibition currently on show at Almine Rech in London, Tom Wesselmann challenges the limits of figurative painting

By Sam Moore

-

A major Frida Kahlo exhibition is coming to the Tate Modern next year

A major Frida Kahlo exhibition is coming to the Tate Modern next yearTate’s 2026 programme includes 'Frida: The Making of an Icon', which will trace the professional and personal life of countercultural figurehead Frida Kahlo

By Anna Solomon

-

A portrait of the artist: Sotheby’s puts Grayson Perry in the spotlight

A portrait of the artist: Sotheby’s puts Grayson Perry in the spotlightFor more than a decade, photographer Richard Ansett has made Grayson Perry his muse. Now Sotheby’s is staging a selling exhibition of their work

By Hannah Silver

-

From counter-culture to Northern Soul, these photos chart an intimate history of working-class Britain

From counter-culture to Northern Soul, these photos chart an intimate history of working-class Britain‘After the End of History: British Working Class Photography 1989 – 2024’ is at Edinburgh gallery Stills

By Tianna Williams

-

Celia Paul's colony of ghostly apparitions haunts Victoria Miro

Celia Paul's colony of ghostly apparitions haunts Victoria MiroEerie and elegiac new London exhibition ‘Celia Paul: Colony of Ghosts’ is on show at Victoria Miro until 17 April

By Hannah Hutchings-Georgiou