ANOHNI addresses a world at war with itself in her Wallpaper* guest editor interview

Musician and artist ANOHNI, guest editor of October 2023 Wallpaper*, seeks new strategies in the face of troubled global realities, centring the powers of feeling, intuition, femininity and motherhood

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Born in Chichester, in the UK, musician and visual artist ANOHNI relocated with her family to Amsterdam for a year when she was seven, and later moved to California when she was ten. On moving to New York to study experimental theatre at NYU, she became involved in the city’s performance scene, starting her career as founder of a nightclub collective called Blacklips Performance Cult. In 1995, ANOHNI began staging trans-surrealist theatre as The Johnsons. In 1998, she assembled a group of musicians and performed her first concert as ‘Antony and the Johnsons’ at The Kitchen in NYC. After touring the world, her second album, I Am a Bird Now, released in 2005, was both a commercial and critical success, earning ANOHNI that year’s Mercury Music Prize. Earlier in 2023, ANOHNI announced the launch of her fifth album under the name ANOHNI and the Johnsons, and she was also invited to be associate artist at the Holland Festival. Her lyrical programme included an orchestral performance of William Basinski’s contemplative masterpiece The Disintegration Loops, as well as the exhibition ‘She Who Saw Beautiful Things’, honouring ANOHNI’s former collaborator Julia Yasuda, and offering what she describes as ‘a vision of enlightened femininity and luxuriant androgyny persevering in memory despite existential threat’.

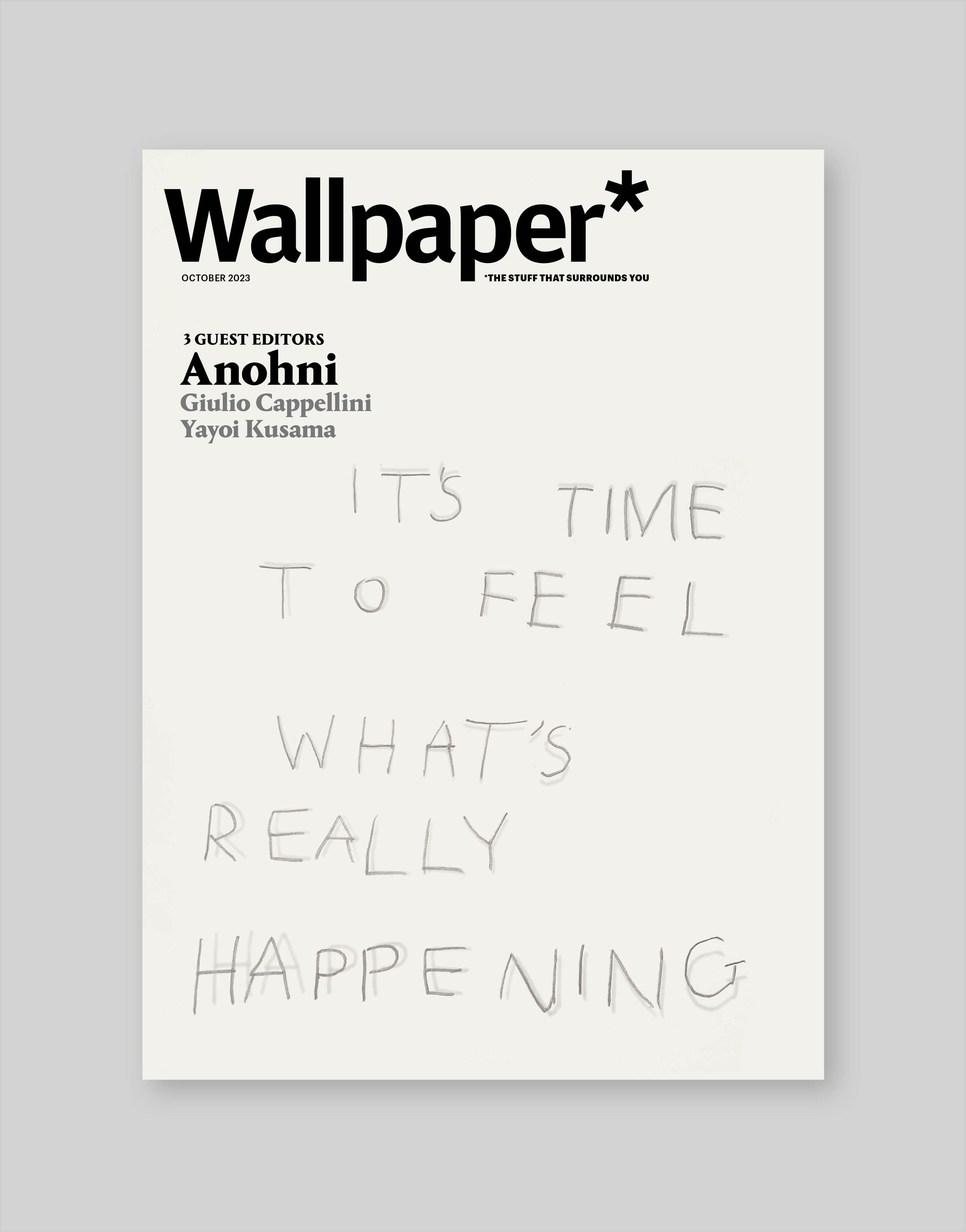

ANOHNI’s guest editor cover for Wallpaper* October 2023 features It’s Time To Feel What’s Really Happening, pencil on paper, (excerpt from My Back Was a Bridge for You to Cross album artwork, 2023)

Here, as guest editor of Wallpaper* October 2023, ANOHNI presents works from that exhibition, held at Huis Willet-Holthuysen in Amsterdam, alongside a photo series, including works by herself and others, set in decaying structures in rural Ireland.

ANOHNI on a new strategy for the troubles of our times

A universe. A body of work for us. What role does an artist have in a world at war with itself? What hope can framed photographs, sculptural works on cloth, museum shows, pencil drawings, the spoken word, ethereal song and beauty provide at a time of grave environmental, political and social unease? ‘I don’t think society is capable of assigning jobs to artists anymore, now that we’re very confused about what creativity might be for,’ says the British-born, America-based musician and visual artist ANOHNI. The job she has assigned to herself: ‘To be useful.’

Untitled (Tryptich featuring Julia Yasuda and Mako Midori), photos by Erika Yasuda, No Date (1979-1984); Dead Ghost, hand-painted silk, 2023

With her solicitous, spectral animism, ANOHNI hopes to determine a new strategy, an emerging ‘metabolisation’ for the troubles of our times. After performing at a TED conference in 2011, a scientist told her that, although her songs were nice, 50 per cent of the world’s species would be extinct by the end of the century, and really, there was ‘no use in crying over spilt milk’. ‘I told him that my role as an artist is to hold space for the emotional, spiritual and psychic ramifications of what he’d just said. There are all these modalities of feeling and receiving beyond the patriarchal method. They really cut off two of our three legs when they allocated all reasonable decisions to rationalists. They cut off intuition. Feeling. Without those, you can do anything you want, no matter the consequences.’

In 2023, ANOHNI was the associate artist at the 76th edition of the Holland Festival, which took place at various locations across Amsterdam in June. The curators asked her to respond to Huis Willet-Holthuysen, a 17th-century canalside residence in the centre of the city, home to Abraham Willet and his wife Louisa Holthuysen at the end of the 19th century. Throughout their life, and for a long time after their death, the duo were framed as ‘deviant’: Holthuysen was supposedly intersex, and Willet a dandy who liked dressing up. For ANOHNI, the house was a kind of ground zero. ‘At first, I didn’t want to do it – the house holds 100 years of homophobia and transphobia, the residents are anonymous, no one really knows anything about them. Whenever you do work like this, you almost have to perform a spell for the space, you try to find a new way of seeing it afresh and free the materiality of the space from some of these atrophied, calcified and broken ideas.’

Hair of a 16 year old trans kid in an abandoned fireplace, 2023

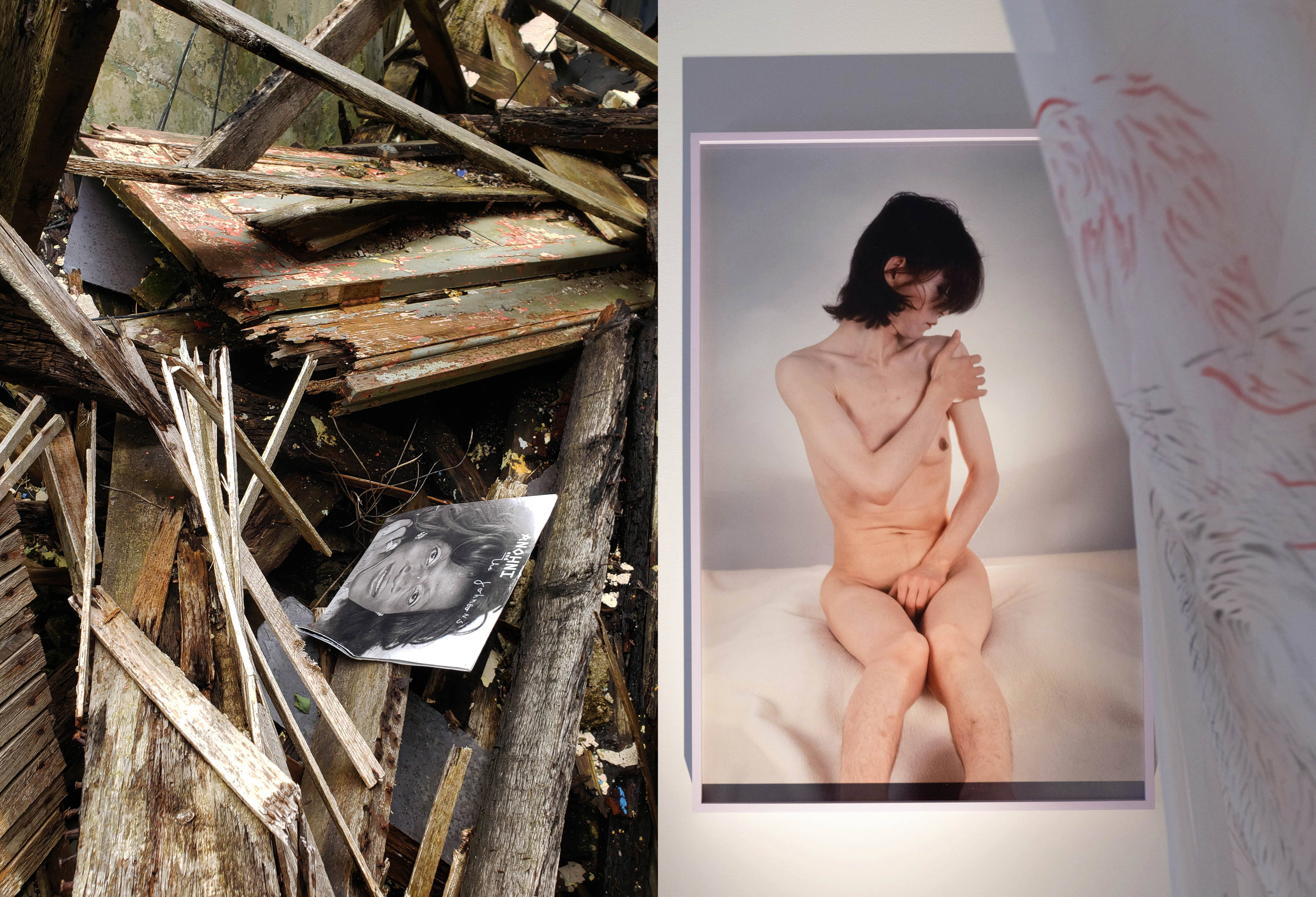

Inside, ANOHNI layered photographs, fabrics, sculpture, video, sound and paintings of her own, which are documented here alongside new interventions within derelict and abandoned rural spaces. Most striking are the 12 full-colour pictures by Erika Yasuda that ANOHNI installed on the top two floors of the house. Yasuda’s wife Julia was one of the founding members of the performance collective The Johnsons, together with ANOHNI and Johanna Constantine, which was formed in New York in 1995. She was a mathematician specialising in set theory, a model, and a pioneering intersex activist.

Throughout the 1970s, Erika often took photographs of Julia and their mutual friend Mako Midori, as well as portraits of their two cats. When she died suddenly in her thirties in 1987, Julia released a limited-edition catalogue of the work, before eventually relocating to New York from Japan. The original prints are lost, so ANOHNI worked with what was left behind when Julia died in 2018 and set about resurfacing the grain of each image scanned from her copy of the original book. Today, the pictures represent a very self-contained, self-perpetuating world of spectral feminine love. In crisp, full colour, they reveal a different realm from the black and white prints in the original book, what ANOHNI calls ‘a more intimate, less obfuscating view into Erika and Julia’s romantic, utopian expression of a world beyond patriarchal influence or binary gender restrictions. A world in which masculinity was a ball of yarn with which the couple sometimes toyed within an essentially feminine universe’.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Polar Exodus, wall mural excerpt, 2022

ANOHNI is deeply penetrating in both her work and her speech. Since arriving in New York in 1990 to study experimental theatre, she has been focused on the emotional, psychological and spiritual ramifications of our proximity to ecological catastrophe. The work shown here presents a world aware of its own fragility yet also wise to its radiant, magical, life-affirming spirit. ‘It echoes the essence of Nature herself – the feminine as an archetype. We’re finally coming to understand the vulnerabilities of the feminine paradigm. Julia and Erika are an iteration of this. I started thinking about cycles of genocide, especially on feminine or gender variant bodies, a rolling tectonic cycle of genocide against a too-vivid expression of feminine power.’ Many of the women in ANOHNI’s circle, from the music duo CocoRosie to artist Kembra Pfahler, share something with the couple: ‘They are punk women that viscerally embody the struggle of female outsiders in crisis responses to patriarchy that is sometimes too visceral to be included within conversations about feminism that occur in academia.’

Installation in Huis Willet-Holthuysen dining room: God’s Vagina, pencil on paper, 2016; Amanda Lepore, Limelight, 1996, photo by ANOHNI

In parallel to the work installed at Huis Willet-Holthuysen, ANOHNI also organised a performance of the sonic artist William Basinski’s The Disintegration Loops, the original completion of which coincided with 9/11. The restaging became a reckoning with a space that ANOHNI mistakenly thought she knew.

For one year in the late 1970s, ANOHNI’s family moved into a building that had once stood opposite the Nazi headquarters of the SS’s intelligence agency and was the main centre for the deportation of Dutch Jews during the Second World War. ‘Unbeknownst to me, my neighbourhood had been used during the war as a processing station from which the Nazis and their Dutch allies sent 70,000 Jews and other “undesirables” to their deaths. To me as a kid, the neighbourhood had seemed paradisical. I have a memory of this as a place of great peace and creative possibility and gentleness. Only in the last few years have I come to understand this deeper context of this space where I grew up.’

Left, Ghost/Moon/rotting wall, 2023; pencil and ink on paper, 2019. Right, White Clown in Downstairs Bedroom, 2023: ANOHNI in The Johnsons’ Miracle Now, 1996, photo by Johanna Constantine

The Disintegration Loops (for Euterpestraat) invited several female ‘elders’ to talk about their experiences as residents of the neighbourhood during the war and, in two instances, as detainees in the buildings. Euterpestraat went through an immediate process of renewal when the war ended in 1945, renamed by the city as Gerritvan der Veenstraat, in honour of individuals within the Dutch resistance, and underrepresenting the harder reality that some of those sent to the dreaded Euterpestaat had been turned over by their Dutch neighbours. ‘I have come to realise that an aura of what might seem like ‘peace’ sometimes lingers in the wake of genocide — in America, in Australia, in Holland. Something more monocultural has been instated in the wake of the eradication of other people and the theft of their wealth. I noticed a kind of emptiness that could have been classified as a kind of sickening “peace” in the aftermath of the worst part of AIDS in New York. In the silence following calamity, capitalism rushes to rebuild and erase from memory the radical thought and diversity that has been vastly diminished.’

ANOHNI’s intervention examined the pheromone of both cultural and physical erasure. Through her work, ANOHNI picks at the disparity between what’s really happening and what we tell ourselves is happening. ‘If we were awake to our feelings, and sensitive to the historical and essential realities embedded in the material world around us, we might be compelled to account collectively in new ways,’ she says.

Left, Julia with Rose, photo by Erika Yasuda, No Date (1979-1984); Martu (Fox), hand-painted silk, 2023

When she released her fifth studio album My Back Was a Bridge for You to Cross in summer 2023, ANOHNI hoped that the work would ‘model my attempts to move with more dignity and resilience through these conversations’. She suggests that we believe we don’t have enough context, and we don’t know how to move through the world with real emotion. We don’t know what real relationships are and almost anything we touch or engage with has become too abstract. If we had to reimagine our whole experience of living – with care, with attention, without data-driven rationalism – everything would slow to a halt. Like babies growing up, we would learn how to see again – smelling, touching, observing, weighing and vetting all things with new meaning. And no longer infantilised by societally sponsored denial, we might be able to reckon with the ethical weight and consequences of our consumption; the truth about our footprints on the planet would finally become less abstract, something to finally reckon with, in an adult way. ‘Most people I know have already resigned themselves to a kind of apocalyptic climax,’ she says. ‘I’m just confounded by the challenge that we’re facing. I’m horrified and shaken and humbled. I’m mortified and ashamed and so dearly wishing that we could forge a different way forward.’

Left, Bridge amid Collapsing Wood: Untitled (Marsha P Johnson), photo by Alvin Baltrop, No Date (1975-1986). Right, Julia, naked, photo by Erika Yasuda, No Date (1975-1986); Martu (Red lines), hand-painted silk, 2023

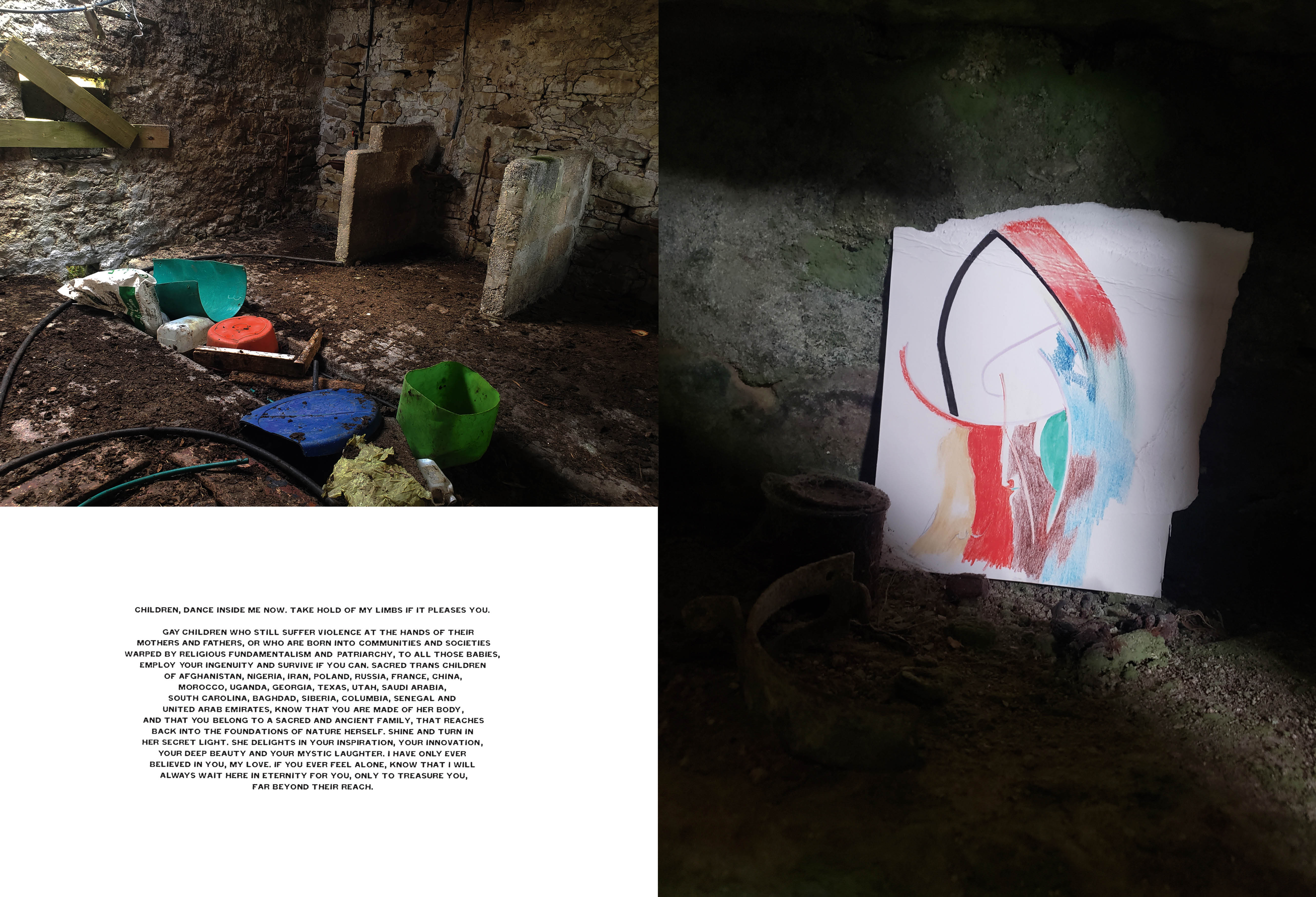

The work presented here is titled It’s Time To Feel What’s Really Happening – but perhaps, we’ve forgotten how to feel. ANOHNI remembers being a nine-year-old growing up in Chichester, West Sussex, staring at the seats in her parents’ car, wondering about the essence of the plastic material stretched over them, and whether in some sense it might be feeling something in its own way. ‘I was raised to believe that only humans had souls, that only humans had spiritual value. That sort of foundational lie about creation is so disruptive and disorienting. It’s confounding. It contradicts the evidence of our senses, yet we eat so many of these falsehoods.’

She looks to the anti-globalist teachings of Vandana Shiva, the ecofeminist and philosopher who stresses that the knowledge held by ‘indigenous people, women and peasants’ is key if we are to find a way through environmental and humanitarian ruin. ‘I listen to Vandana and I realise that what she’s talking about is common sense,’ says ANOHNI. ‘I keep circling this aspect of femaleness in all my work. In my imagination, the enslavement of farm animals preceded the plunder of female creative agency, the defilement of femininity, and the determination that femaleness was a lower caste of humanity. When we were researching for Future Feminism, Kembra described a book she had read that said the male archetype feared drowning in menstrual blood. That rang true to me. Why else would maleness and male religions be so desperate to escape the confines of a voluptuously feminine universe, a primordial oasis bursting with stars, flashes of fire and volatility, and in which men are entirely comprised of and pour from women’s bodies? It’s an infantile impulse to escape the kaleidoscope of an endless female totality. Patriarchal authorities seem to have suggested two solutions. Either a retreat into a monocultural heaven in which nothing occurs, a stasis of whiteness, a retreat into some kingdom of heaven, that sounds almost like a paralysis in whiteness. Their other strategy has been to abscond with traditionally female agency using technological innovation to posture through attempting to rewrite the narrative, recasting every womb as an enslaved channel through which male genius pours, and which one day they hope to be entirely rid of. The sight of the richest men on Earth sending up pathetic little space dildos in the hope of growing lettuce on a dead planet like Mars seems to epitomise this tragic folly. As an infant, he pounded on his mother’s breast. Now grown, he seeks to cut his mother’s throat, imagining that somehow he can live without her, without water, without air, without life, without diversity, without comfort. He hates femaleness. He compensates for this by seeking to destroy her creations.’

Left, Installation in Huis Willet-Holthuysen reception room: Julia’s hands, photo by Don Felix Cervantes with ANOHNI, 2008. Right, Kazuo Ohno in Desolate Fireplace, 2023: SYNCHRONICITY postcard and portrait by Naoya Ikegami, 2014

ANOHNI’s plea is that we embrace the discomfort. We should ask those who have a more symbiotic relationship with the natural world for guidance. ‘People can more easily visualise the collapse of the entire biosphere in the next 50 years than a shift towards more archetypally feminine paradigms. Most people still think that it is a laughable conceit to think that women, who have been oppressed for more than 2,000 years, might collectively have unique access to different strategies for species reorganisation and survival. Even the guys inventing AI are saying that they are scared of this technology, they are stating it point blank, but because they are expressing emotion, their fear is irrelevant,’ she says. ‘In patriarchy, any emotion is grounds for exclusion from conversations of reason. It’s time to feel what’s really happening. Some gender theorists would like to convince us that all modern gender means the eradication of the gender binary. In my view, the one untapped natural resource, our final secret weapon, the sleeper cell of knowledge within our species, that may yet save us, is motherhood. The most radical thing we could do now is to raise up feminine paradigms, centre the values and knowledge of motherhood, and trust our mothers to lead us forward. It will require a revolution of humility, a great surrendering. Then we start to do what our grandmothers collectively decree. What have we got to lose?’ @anohni

This article appears in the October 2023 issue of Wallpaper*, available in print, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today

Left, Triangle, photo by Erika Yasuda, No Date (1979-1984). Right, Julia Gazing into the Mirror, photo by Erika Yasuda, No Date (1979-1984); ANOHNI, 14, hand-painted silk, 2023

Left Julia with Rose, Plastic, Soil, Filth, 2023, photos by Erika Yasuda, No Date (1979-1984). Right, Divine on a Bed of Rotting Hay, 2023; Divine, by Peter Hujar, gelatin silver print, 1975

Left, Installation in Huis Willet-Holthuysen boardroom: Euterpestraat street sign, 1945; Untitled, ink and newsprint collage, 2012. Right, James Purdy, Anne Frank, Billie Holiday, Debris, 2023

Photos by Erika Yasuda, No Date (1979-1984); hand-painted silks, 2023

Left, ANOHNI within Johanna Constantine’s Face, self-portrait by ANOHNI with Nomi Ruiz; 2 Moons, line drawing collage, 2017. Right, Julia with American Flag, video still, Johnsons shoot, Williamsburg 1996, Camera by Eva Love; Girl, 7, hand-painted silk, 2023

Left, Installation in Huis Willet-Holthuysen bedroom: Green Light, Nowhere, 2023: Untitled pencil and collage, 2018. Right, Locked Green Bedroom, 2023; Polar Exodus, wall mural excerpt, 2022

Left, Colored Plastic in Animal Stall, 2023; Children Dance Inside Me Now (excerpt from My Back Was a Bridge for You to Cross album artwork), 2023. Right, Secret Colour, 2023: Untitled, pencil on paper, 2022

Left, Installation in Huis Willet- Holthuysen bedroom: Skull, Sleeping, 2023: Untitled, ink and paper collage, 2016. Right, Installation in Huis Willet-Holthuysen bedroom: Blue Light, Please Help Us, 2023: Numerous drawings, pencil, ink, paint, paper, 2020; Untitled, newsprint collage, 2012; Louisa Holthuysen’s hairbrush and nightclothes

Photography at Huis Willet-Holthuysen: Sophie Gladstone and ANOHNI

Photography in Ireland: ANOHNI

Drawings, sculptures, installations and design: ANOHNI

Production: Benedikt Terwiel

London based writer Dal Chodha is editor-in-chief of Archivist Addendum — a publishing project that explores the gap between fashion editorial and academe. He writes for various international titles and journals on fashion, art and culture and is a contributing editor at Wallpaper*. Chodha has been working in academic institutions for more than a decade and is Stage 1 Leader of the BA Fashion Communication and Promotion course at Central Saint Martins. In 2020 he published his first book SHOW NOTES, an original hybrid of journalism, poetry and provocation.