Anthea Hamilton is a force to be reckoned with at Thomas Dane Gallery

The Turner Prize nominee transforms the London gallery with soft sculptures, tiled furniture and immersive wall treatments in her incisive exhibition ‘The Prude’

The dancing badger is nowhere to be seen. Missing too is the gold and white bird with the tie-dye socks. The install at Mayfair’s Thomas Dane Gallery is well under the way. I tip-toe through wet paint and plastic sheeting. We speak over the metallic blast of drills. Maybe the animals of ‘The Squash’ will join us for the opening party.

Anthea Hamilton is embarking on her first high-profile solo exhibition in a commercial London gallery. A native south Londoner who graduated from the Royal College of Art, Hamilton spent much of her twenties and thirties working independently and below the radar before a series of strong and provocative shows culminated in her being shortlisted for the 2016 Turner Prize.

While Hamilton did not win the Turner Prize, her show proved to be the most popular of the shortlisted works. Her huge sculpture of a pair of hands digging into a pair buttocks, the parted legs acting as a doorway, became the selfie shot of the summer – an example of a piece of contemporary art reaching far out beyond the contemporary art scene.

A year later, in 2017, Hamilton, who is 41, became the first black woman to be awarded a commission to create a work for Tate Britain's Duveen Galleries – a 100-yard neo-classical sculpture court. Alex Farquharson, Tate Britain’s director, said at the time: ‘Anthea Hamilton has made a unique contribution to British and international art with her visually playful and thoughtful works.’

Playful is the word. Hamilton used mime artists while exhibiting at the Frieze art fair in New York in 2016. At the British Art Show in the same year, she installed a live ant farm in which cut-out photographic portraits were provocatively stationed.

But the Duveen Galleries is a different stage entirely. It’s a big space, and a make or break commission, spoken of as a bellwether for the ascent or plight of the artists chosen to use it as a canvas. It’s fair to say Hamilton’s use of The Duveen was a success. For an exhibition titled ‘The Squash’, she referenced the early 20th-century French writer and dramatist Antonin Artaud and his call for the ‘physical knowledge of images’, employing performers to act out dramas in relation to sculptures she installed within the Duveen. The badger and the gold-white bird were there, alongside many other characters.

Now, at Thomas Dane Gallery, Hamilton is being pulled into the warm embrace of the high-end and very monied London art world. This is an artist who has often existed at the fringes of the industry, and once said to Frieze: ‘I’m not sure I believe the possession of works of art is necessary.’ The London gallery has only come calling fairly recently. Her response to their attention is fascinating.

The first thing one sees when entering the exhibition, on specially-made walls, is a huge drawing of a smiling black woman as she walks into what appears to be a meshed prison-like structure. The etching would, if it appeared on the street outside, almost certainly be decried as being racist before being wiped clean. Here, it is titled The Prude.

Amid the gallery, in which we too are encased, are soft sculptures of the insects, moths and butterflies that Hamilton originally showed at the Vienna Secession. These are juxtaposed with pieces of ‘furniture’ – sculptures made from geometric tile constructions similar to those from the Tate Duveen installation.

Hamilton, to be blunt, wouldn’t be the first artist to turn insects into accessories (look at Damien Hirst). Or, for that matter, take what could be an architectural detail of a swimming pool and place it in a gallery (look at Marcel Duchamp). But the presence of The Prude seems to transform the dialogue of the entire exhibition.

Although Hamilton wasn’t available for interview when I toured the exhibition, I asked her to explain the presence of the etching to me. The image, she tells me over email, is from 2000 – a cover produced by the veteran American cartoonist Robert Crumb for Fate magazine. It was then used as the lead image for Crumb’s exhibition ‘De l’Underground à la Genèse’ at Musée d'Art Moderne in Paris.

The character, I’m told, was originally called Sasquatch Lady; Sasquatch being another term for Bigfoot, the almost mythical hair-covered, primate-like creature that walked like a human being and was said to be a between 6 and 15 feet. ‘I was living in Paris at the time of that show and Crumb’s drawing was postered all over the Metro public transport,’ Hamilton says. ‘Her confident look kept catching my eye.’ The presence of Crumb’s work is further complicated by the artist’s own on-the-record prejudice towards women and African-Americans.

In a 2010 essay exploring blackness in the American psyche through the comics of Winsor McCay and Crumb, the academic Edward Shannon notes a direct quote from the latter regarding his insecurity towards women: ‘I have these hostilities toward women. I admit it – it’s out there in the open, it’s very strong. It ruthlessly forces itself out of me onto the paper. I hope that somehow revealing that truth about myself is helpful... but I have to do it.’

Shannon also notes how Crumb’s work is filled with derogatory images of African-Americans. The artist portrays black women in particular as essentially indigenous and tribal. Shannon refers to the creation of a Crumb character called Angelfood McSpade, who made her comics debut in the second issue of Zap Comix in 1968. She is depicted as a large, bare-breasted tribeswoman, dressed in a skirt made out of palm tree leaves, drawn with large lips and golden rings around her neck and in her ears. Her name references angel food cake and the racial slur ‘spade’.

So why has Hamilton used such a key moment of visibility to reference, draw attention to, and, in some ways, repurpose Crumb’s work in such a monumental way? ‘My relationship to Robert Crumb’s representations of the female is complex – it couldn’t be any other way,’ Hamilton tells me. ‘This image has the highly economic capacity to do so many different things – personally, historically, culturally, and on and on – yet all the time her smile doesn’t waver. Formally, in The Prude, her dynamic pose, her as a figure in motion, animates the static walls, pulls them into action, carrying the complexity of the image as a cultural object around the space with it, creating a space for the reading of the building, a gallery, and the three-dimensional works on show.’

Hamilton has had a long association with Crumb’s work. ‘I had previously used this Robert Crumb image for a wallpaper and across the 12m high façade of La Sucrière building for the 13th Lyon Biennale in 2015,’ she says. ‘I wondered how the image might function some four years later. How much have the viewing conditions – and by that I mean a wider conversation of culture, politics, nostalgia and how we look back to earlier periods – changed the way this image functions.’

It’s a hard, knotty and fascinating question, displayed with a confidence, wit and vim that is nothing short of audacious; the signature, maybe, of one of the most discursive – and important – contemporary artists working in Britain today.

INFORMATION

‘The Prude’ is on view from 8 March – 18 May. For more information, visit the Thomas Dane Gallery website

ADDRESS

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Thomas Dane Gallery

3 and 11 Duke Street St James’s

London SW1Y 6BN

Tom Seymour is an award-winning journalist, lecturer, strategist and curator. Before pursuing his freelance career, he was Senior Editor for CHANEL Arts & Culture. He has also worked at The Art Newspaper, University of the Arts London and the British Journal of Photography and i-D. He has published in print for The Guardian, The Observer, The New York Times, The Financial Times and Telegraph among others. He won Writer of the Year in 2020 and Specialist Writer of the Year in 2019 and 2021 at the PPA Awards for his work with The Royal Photographic Society. In 2017, Tom worked with Sian Davey to co-create Together, an amalgam of photography and writing which exhibited at London’s National Portrait Gallery.

-

Klára Hosnedlová transforms the Hamburger Bahnhof museum in Berlin into a bizarre and sublime new world

Klára Hosnedlová transforms the Hamburger Bahnhof museum in Berlin into a bizarre and sublime new worldThe artist's installation, 'embrace', is the first Chanel commission at Hamburger Bahnhof

-

We test the all-new Asus Zenbook A14, a laptop shaped around new materials

We test the all-new Asus Zenbook A14, a laptop shaped around new materialsAsus hopes its Ceraluminium-based Zenbook laptops will bring brightness and lightness to your daily portable computing needs

-

Paris art exhibitions to see in May

Paris art exhibitions to see in MayRead our pick of the best Paris art exhibitions to see in May, from rock 'n' roll photography by Dennis Morris at MEP to David Hockney at Fondation Louis Vuitton

-

The UK AIDS Memorial Quilt will be shown at Tate Modern

The UK AIDS Memorial Quilt will be shown at Tate ModernThe 42-panel quilt, which commemorates those affected by HIV and AIDS, will be displayed in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in June 2025

-

Meet the Turner Prize 2025 shortlisted artists

Meet the Turner Prize 2025 shortlisted artistsNnena Kalu, Rene Matić, Mohammed Sami and Zadie Xa are in the running for the Turner Prize 2025 – here they are with their work

-

‘Humour is foundational’: artist Ella Kruglyanskaya on painting as a ‘highly questionable’ pursuit

‘Humour is foundational’: artist Ella Kruglyanskaya on painting as a ‘highly questionable’ pursuitElla Kruglyanskaya’s exhibition, ‘Shadows’ at Thomas Dane Gallery, is the first in a series of three this year, with openings in Basel and New York to follow

-

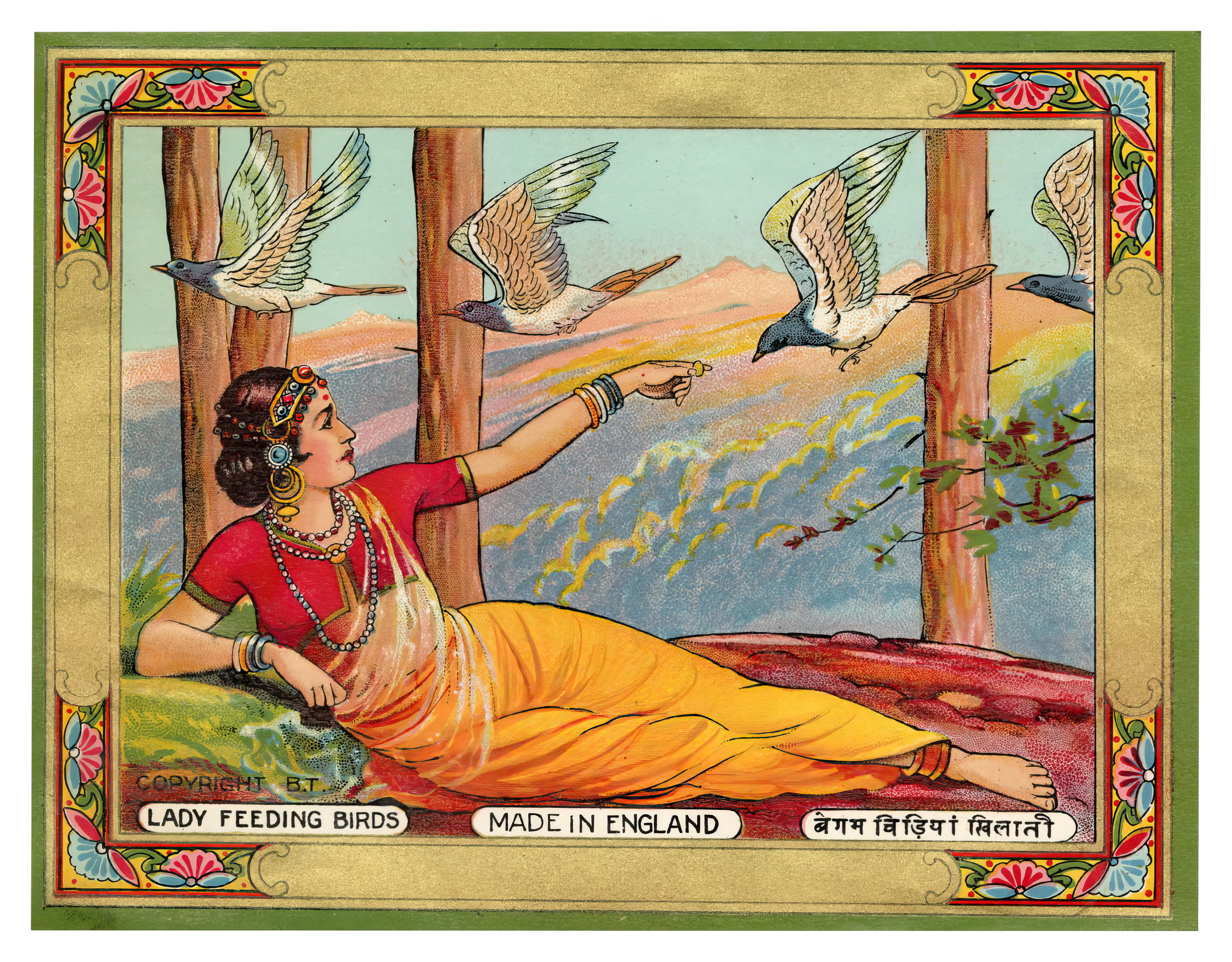

The art of the textile label: how British mill-made cloth sold itself to Indian buyers

The art of the textile label: how British mill-made cloth sold itself to Indian buyersAn exhibition of Indo-British textile labels at the Museum of Art & Photography (MAP) in Bengaluru is a journey through colonial desire and the design of mass persuasion

-

Artist Qualeasha Wood explores the digital glitch to weave stories of the Black female experience

Artist Qualeasha Wood explores the digital glitch to weave stories of the Black female experienceIn ‘Malware’, her new London exhibition at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, the American artist’s tapestries, tuftings and videos delve into the world of internet malfunction

-

Ed Atkins confronts death at Tate Britain

Ed Atkins confronts death at Tate BritainIn his new London exhibition, the artist prods at the limits of existence through digital and physical works, including a film starring Toby Jones

-

Tom Wesselmann’s 'Up Close' and the anatomy of desire

Tom Wesselmann’s 'Up Close' and the anatomy of desireIn a new exhibition currently on show at Almine Rech in London, Tom Wesselmann challenges the limits of figurative painting

-

A major Frida Kahlo exhibition is coming to the Tate Modern next year

A major Frida Kahlo exhibition is coming to the Tate Modern next yearTate’s 2026 programme includes 'Frida: The Making of an Icon', which will trace the professional and personal life of countercultural figurehead Frida Kahlo