Antony Gormley interview: ‘We’re at more than a tipping point. We’re in a moment of utter crisis’

We visit the London studio of British sculptor Antony Gormley ahead of his major new show ‘Body Field’ at Xavier Hufkens Brussels

‘Are you from Wallpaper*?‘ cries a voice in motion, originating from a helmeted, high-vis-clad cyclist hurling down an industrial street in Islington on an early October morning. The voice belongs to a very lively Antony Gormley, one of the most recognisable, accoladed artists of a century.

Gormley leads me, and the bicycle, through the studio gate, best described as a barricade, into the expansive forecourt of his purpose-built creation palace, designed by David Chipperfield in 2003. It’s formed of seven white pitched roofs, hugged on each side by galvanised steel staircases. It’s the sort of industrial-scale studio that caters for stratospheric-level thoughts, of which Gormley has many.

Installation view of Antony Gormley: ‘Body Field’ at Xavier Hufkens Brussels

Inside the double-height space are Gormley’s bodies, standing upright and protruding horizontally from walls, ghostly, fractured suggestions of figures, in lines, pixels, and knots and a sea of maquettes, including one for Alert, a recent (and somewhat divisive) sculpture for Imperial College London.

I’m interviewing Gormley ahead of his show ‘Body Field’ at Xavier Hufkens’ new St-Georges space in Brussels. The gallery, a modernist monolith designed by Robbrecht & Daem architects, opened earlier this year. Gormley is impressed: ‘To see the equivalent of the Met Breuer suddenly inserted into this comfortable but quite self-satisfied range of 19th-century row-house designs is just so exciting.’

Fall IV, 2022, by Antony Gormley

Gormley has been collaborating with Hufkens for 35 years and ‘Body Field’ marks his ninth show with the gallery. ‘I think we’re friends united in a common wish for art to be a present but lasting force in changing the world,’ he says of his gallerist.

‘Body Field’, spanning four floors of the gallery, is organised into three zones: the mapping of urban context, the mapping of the interior network of bodily emotion, and the fusion of self and other. And there’s a lot to digest.

The show places humanity in a ‘grid’ of rapid urbanisation, the equally as gridlike world of cyber communication, our ‘dangerous’ separation from the elemental, our ‘collective condition of narcissistic self-observation’, and poses a key question: ‘What is a human being now?’

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

‘We’ve never had tools of self-knowing at our disposal so immediately before, or tools of self-destruction so easily available. And we’re at more than a tipping point. We’re in a moment of utter crisis.’

Installation view of Antony Gormley: ‘Body Field’ at Xavier Hufkens Brussels

The show begins with Run III, a sculpture Gormley describes as an ‘attempt at making a 3D drawing that describes the architecture that’s already there’. It comprises a 153m-long steel tube that ebbs and flows to depict the domestic heights of chairs, tables and windowsills, emphasising the infrastructure that would ordinarily live on the periphery of muscle memory. This is not simply sculptural, Gormley notes, but performative. ‘There is a sense that it’s articulating your movements through space. The body of the viewer is forced into a kind of choreography.’

Corner offers a change in tempo, and is the first of two concrete works that bookend the show. This ‘bunker for one’ features a gaping orifice leading to a void that would accommodate a body. Is this a womb or tomb? Or perhaps it’s a meditation on a bound body with a free mind, or even a reflection on an urbanised world rich in manmade infrastructure yet devoid of humanity. As expected, the answer is more loaded. ‘Vernadsky’s promise of the noosphere has been materialised in the world wide web,’ he says. ‘Our ability to know about things that we will never physically experience has never been equalled and is now universal. The zone of that freedom is all internal… all we need to do is close our eyes and we are in a space with no dimensions, that has no objects, and is totally extensive.’

Corner, 2022, by Antony Gormley

When thinking about Antony Gormley’s best-known works – The Angel of the North, Event Horizon or Another Place – the overbearing sentiment is that of bodily solitude in environmental expanses. In a curious departure, ‘Body Field’ debuts Gormley’s Double Blockworks, the artist’s ‘repeated investigation into the relationship between mitosis and sexual congress or the confusion of the two’.

One could offer infinite interpretations for these intriguing duets: division of the self (the casts were based on scans of Gormley’s body clasping an existing singular blockwork); the increasingly polarised self, or extreme notions of ‘self’ and ‘other’ in global identity politics. Or maybe it’s more obvious and even less tangible: a story of love. ‘The idea of two bodies that are in a way unique, but similar, have a balanced relationship with each other, are proximate and therefore sharing the same air,’ says Gormley, who developed the idea during Covid-19 isolation. ‘The most successful work is where two bodies have found a way of occupying space together where you can’t quite tell which block belongs to which.’

Nest, 2021, by Antony Gormley

Importantly, for these works, Gormley drew on Michelangelo’s ultimate unfinished masterpiece – the Rondanini Pietà (1552-64), which depicts the Virgin Mary cradling the flaccid body of the dead Christ. For Gormley, it is also a ‘picture of the artist in relation to the work’, of a living artist breathing life into inanimate material; striving, in an obsessive process of revision, perhaps in vain, to give thought and feeling to raw material. ‘I just find it unbelievably inspiring and powerful,’ says Gormley. ‘Why do [we] continually try to use our energy to transform the residue of geological time into something that approximates or pictures life? Well, we do it because we know we’re going to die.’

Gormley has been known to experiment beyond the bounds of physical matter. In a 2017 project with Acute Art and astrophysicist Priya Natarajan, titled Lunatick, he turned the human body into an intergalactic spaceship, through VR. Although he describes the experiment as fun, he concluded that ‘virtual reality is better dealing with space than it is dealing with objects’.

Installation view of Antony Gormley: ‘Body Field’ at Xavier Hufkens Brussels

‘Sculpture becomes so important in a time where we are asked to leave our bodies behind, either through screens, VR headsets or the Metaverse,’ he says. ‘While the virtual gives us extraordinary godlike powers, to fly to the moon, the necessary correlative balancing of that is art in all its forms of first-hand experience: seeing paint on canvas or a lump of displaced material that then you’re invited to reconsider because it’s found a new situation in the world. What sculpture offers is the reinforcing of the palpable [and the] experience of touchable, feelable things in a space that you share, something that you can walk through, walk around and be with in time.’

In ‘Body Field’, an entire floor is dedicated to nine of Gormley’s Knotwork sculptures, which use interweaving linear formations that cluster to emphasise areas of compression, emotion or pain. As Gormley describes, they are ‘an attempt to articulate the pathology of a body. Not in terms of the mechanics, but in terms of its emotional zone of tension and fluidity.’

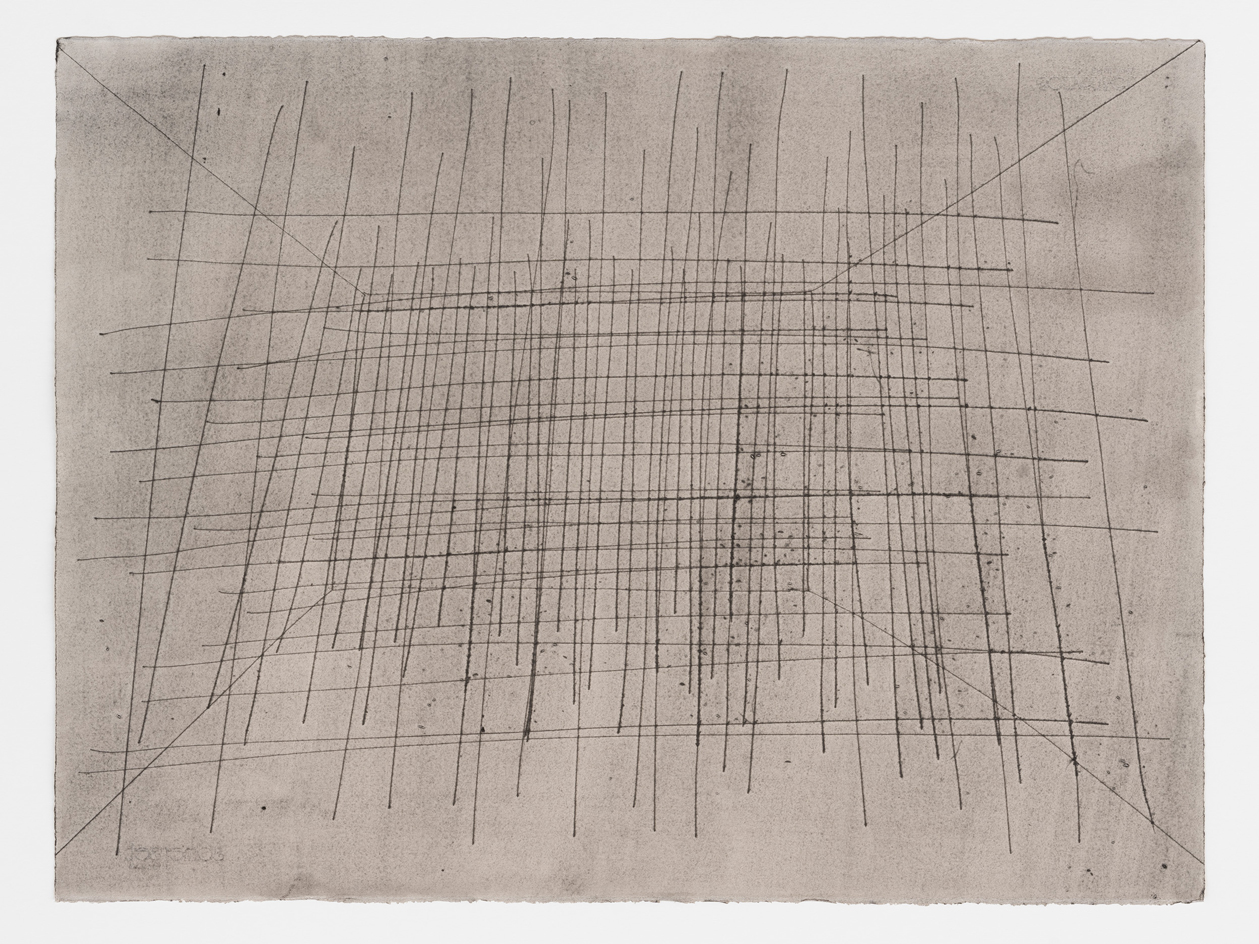

Hatch I, by Antony Gormley

On the top floor are four cosmic drawings. ‘I realised that the drawings were utterly essential to the way that I work. They’re a kind of seedbed of everything. I draw every day. I realised that I hadn’t acknowledged their importance adequately. They act as a catalyst for people to be constantly aware of the bigger picture, the truth of an expanding universe… all the determinants that we take for granted are not there by chance; [that] the air we breathe [and] the atmosphere we depend on is the result of the activity, bacteria or archaea that started 3.7 billion years ago.’

‘You might say, “What the fuck has this got to do with a sculpture exhibition?” Well, I think it has a lot. If sculpture is about trying to make sense of the material phenomena that surround us, [then] these immersions or connectivities are really important,’ he says. ‘All the works in the show are diagnostic instruments through which we can perhaps begin to understand our own condition.’

Retreat (Frame), 2021, by Antony Gormley

If, as Gormley claims, the body is a place as opposed to an object, then his work is perhaps well placed to house it all: the burden of occupying a human body, and the freedom of the conscious mind, our strained, unsustainable dependence on the earth’s resources, and our delusions about liberated individualism.

I leave Gormley’s studio with a mind blown and a brain in knots. He is an artist of microscopic analyses and maximalist aspirations. His verbal justifications, like his work, are not just conceived, but immaculately sculpted before being let out into the world. A package of sculptural prowess, conceptual ingenuity and hyper-contextualisation is what sets Gormley apart; in which making is afforded equal importance as giving voice to what’s made.

Installation view of Antony Gormley: ‘Body Field’ at Xavier Hufkens Brussels

Antony Gormley: ‘Body Field’, until 17 December 2022 at Xavier Hufkens, St-Georges, Brussels. antonygormley.com; xavierhufkens.com

Harriet Lloyd-Smith was the Arts Editor of Wallpaper*, responsible for the art pages across digital and print, including profiles, exhibition reviews, and contemporary art collaborations. She started at Wallpaper* in 2017 and has written for leading contemporary art publications, auction houses and arts charities, and lectured on review writing and art journalism. When she’s not writing about art, she’s making her own.

-

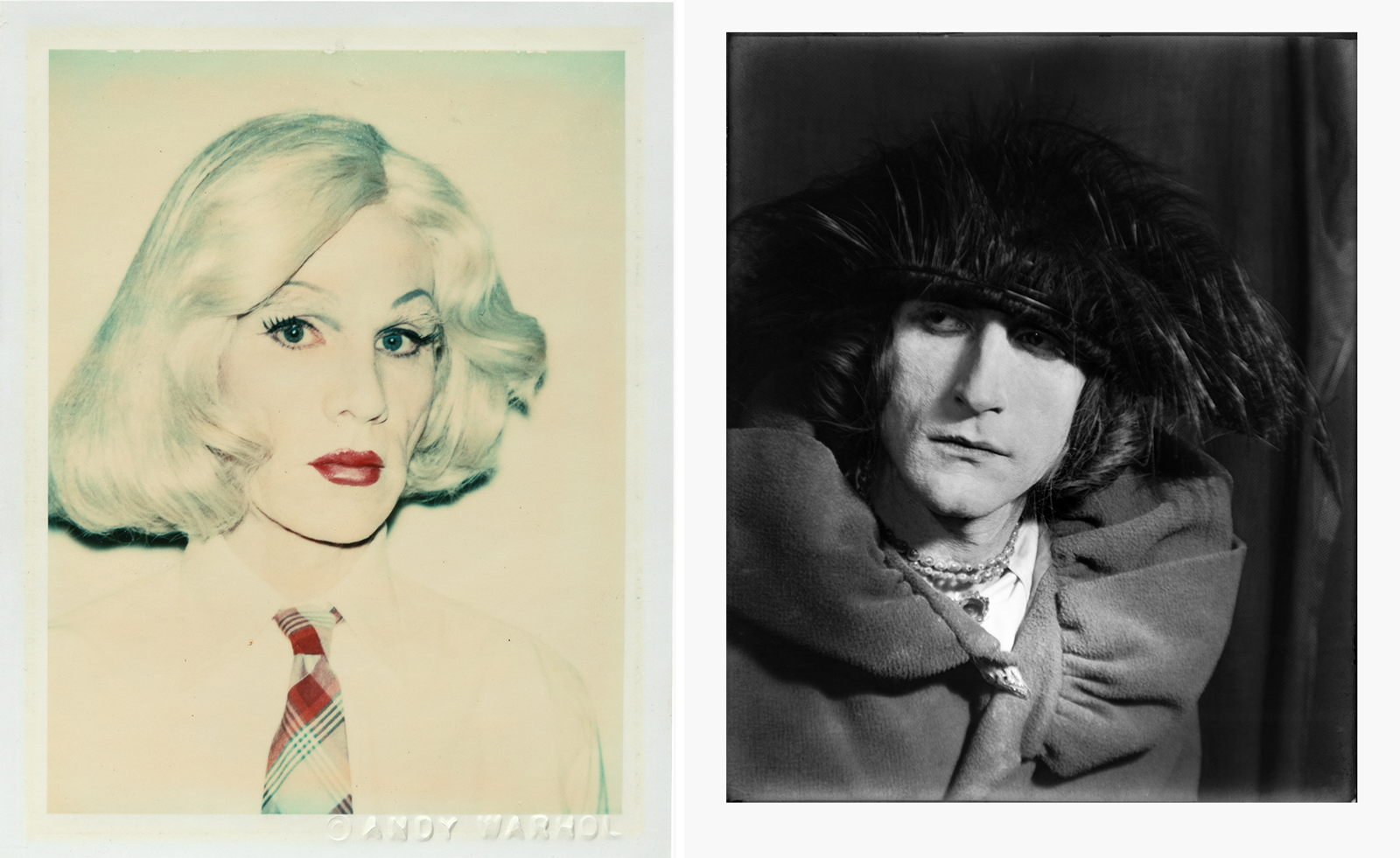

From Rembrandt to Warhol, a Paris exhibition asks: what do artists wear?

From Rembrandt to Warhol, a Paris exhibition asks: what do artists wear?‘The Art of Dressing – Dressing like an Artist’ at Musée du Louvre-Lens inspects the sartorial choices of artists

By Upasana Das

-

Meet Lisbeth Sachs, the lesser known Swiss modernist architect

Meet Lisbeth Sachs, the lesser known Swiss modernist architectPioneering Lisbeth Sachs is the Swiss architect behind the inspiration for creative collective Annexe’s reimagining of the Swiss pavilion for the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025

By Adam Štěch

-

A stripped-back elegance defines these timeless watch designs

A stripped-back elegance defines these timeless watch designsWatches from Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels, Rolex and more speak to universal design codes

By Hannah Silver

-

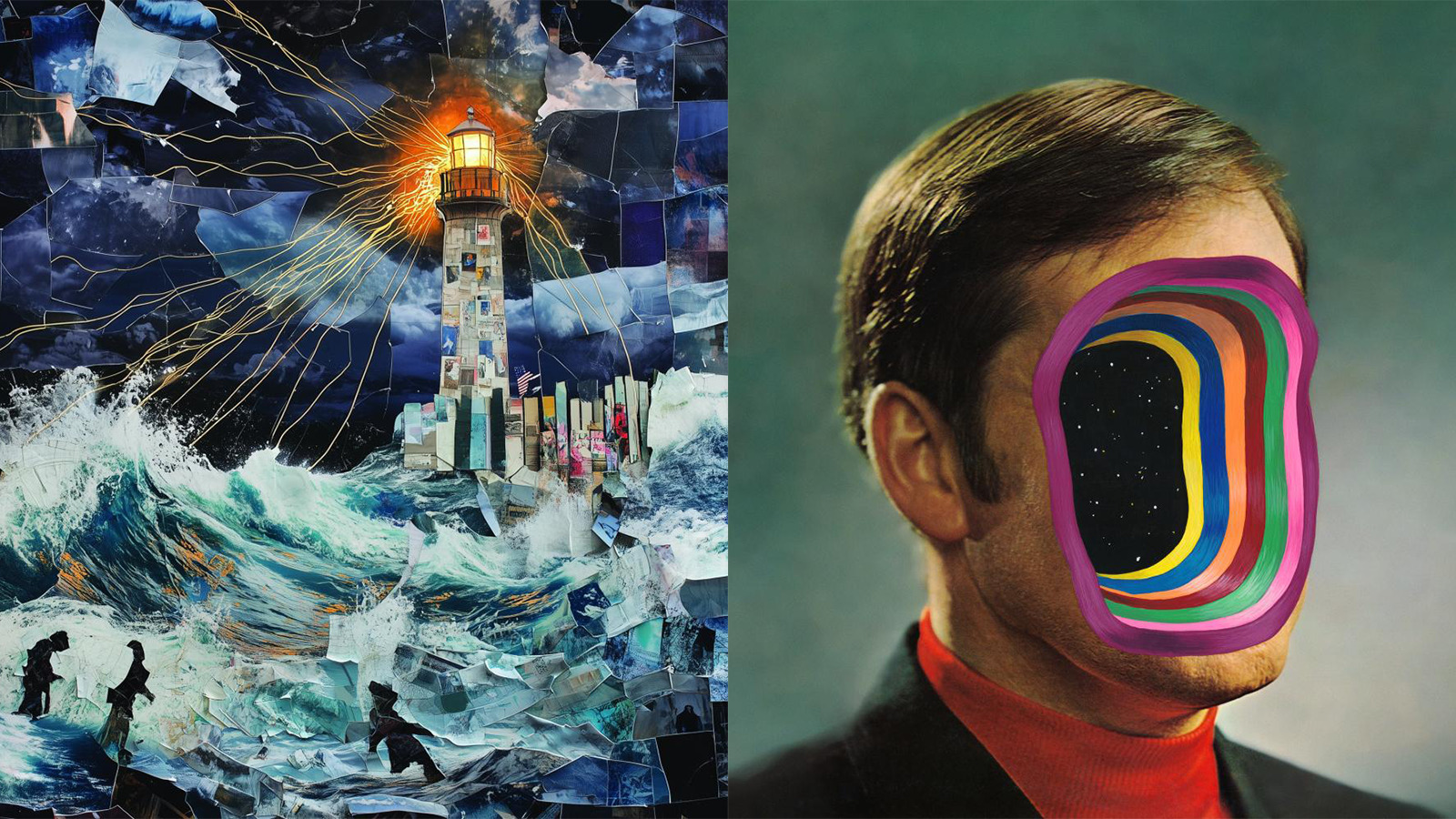

The charity record sale with a difference, Secret 7”, is back

The charity record sale with a difference, Secret 7”, is backThe initiative sees 700 vinyls in one-of-a-kind record sleeves designed by world-class artists exhibited and auctioned to raise money for charity

By Anna Solomon

-

Year in review: top 10 art and culture interviews of 2024, as selected by Wallpaper’s Hannah Silver

Year in review: top 10 art and culture interviews of 2024, as selected by Wallpaper’s Hannah SilverFrom Antony Gormley to St. Vincent and Mickalene Thomas – art & culture editor Hannah Silver looks back on the creatives we've most enjoyed catching up with during 2024

By Hannah Silver

-

Artist Emmanuelle Castellan’s textural takeover in Brussels

Artist Emmanuelle Castellan’s textural takeover in BrusselsLa Verrière gallery in Brussels and Fondation d’entreprise Hermès present ‘Spektrum’, infused with colour and texture by the works of Emmanuelle Castellan

By Hannah Silver

-

The ageing female body and the cult of youth: Joan Semmel in Belgium

The ageing female body and the cult of youth: Joan Semmel in BelgiumJoan Semmel’s ‘An Other View’ is currently on show at Xavier Hufkens, Belgium, reimagining the female nude

By Hannah Silver

-

‘I don't know what art is, but we have to make these things to understand ourselves’: Antony Gormley in New York

‘I don't know what art is, but we have to make these things to understand ourselves’: Antony Gormley in New YorkWallpaper* meets Antony Gormley as his new exhibition, ‘Aerial’ opens at White Cube New York

By Hannah Silver

-

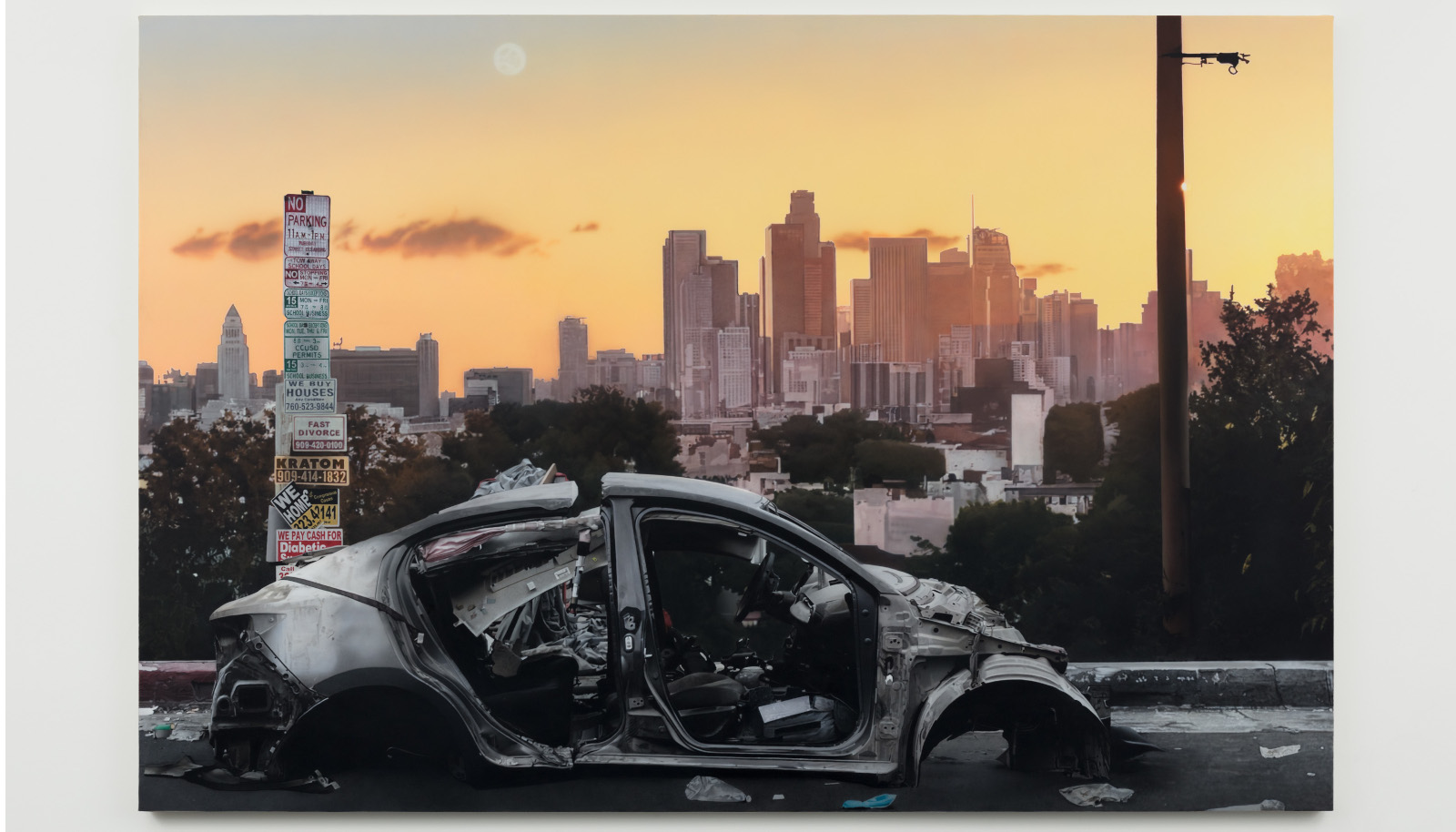

‘Heaven ’N’ Earth’: Sayre Gomez blurs the reality and illusion of Los Angeles

‘Heaven ’N’ Earth’: Sayre Gomez blurs the reality and illusion of Los AngelesSayre Gomez’s ‘Heaven ‘N‘ Earth’ at Xavier Hufkens in Brussels explores the contrasts between wealth and poverty, reality and illusion in Los Angeles

By Finn Blythe

-

Cyprien Gaillard on chaos, reorder and excavating a Paris in flux

Cyprien Gaillard on chaos, reorder and excavating a Paris in fluxWe interviewed French artist Cyprien Gaillard ahead of his major two-part show, ‘Humpty \ Dumpty’ at Palais de Tokyo and Lafayette Anticipations (until 8 January 2023). Through abandoned clocks, love locks and asbestos, he dissects the human obsession with structural restoration

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Year in review: top 10 art interviews of 2022, chosen by Wallpaper* arts editor Harriet Lloyd-Smith

Year in review: top 10 art interviews of 2022, chosen by Wallpaper* arts editor Harriet Lloyd-SmithTop 10 art interviews of 2022, as selected by Wallpaper* arts editor Harriet Lloyd-Smith, summing up another dramatic year in the art world

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith