Antwaun Sargent's ‘Social Works’ presents a vision of a more inclusive art world

Critic and curator Antwaun Sargent’s first show for Gagosian is a multifaceted exploration of Black social practice, as featured in Wallpaper’s August 2021 issue

For centuries, Black Americans have built, maintained and improved coping strategies to overcome countless barriers to their safety and success. Drawing creative inspiration from oral traditions, spiritual practices and learned experience, they have sought and converted spaces to occupy and define.

This multigenerational feat has long been the expertise of the New York-based critic and curator Antwaun Sargent. For his first show as a director at Gagosian, Sargent has gathered a range of artists at different stages of their career, working in different media, but who all have the same goal: creating and dissecting space for the betterment of themselves and their communities.

‘Social Works’, which opened on 24 June at Gagosian’s West 24th Street gallery, showcases site-specific works by David Adjaye, Theaster Gates, Linda Goode Bryant, Rick Lowe, Titus Kaphar and many others. The show (and Sargent’s role at Gagosian) builds on over ten years of conversations with Black American artists. In this time he has started fires and put them out, curated shows and authored books, written diatribes and offered anecdotes. Every project Sargent takes on is broached with searing criticality, a staunchly realistic interpretation of what is and what can be, all presented with an unapologetic undertone of self-advancement. With, of course, the caveat that his own advancement swings a pendulum that hits many other notes on its way.

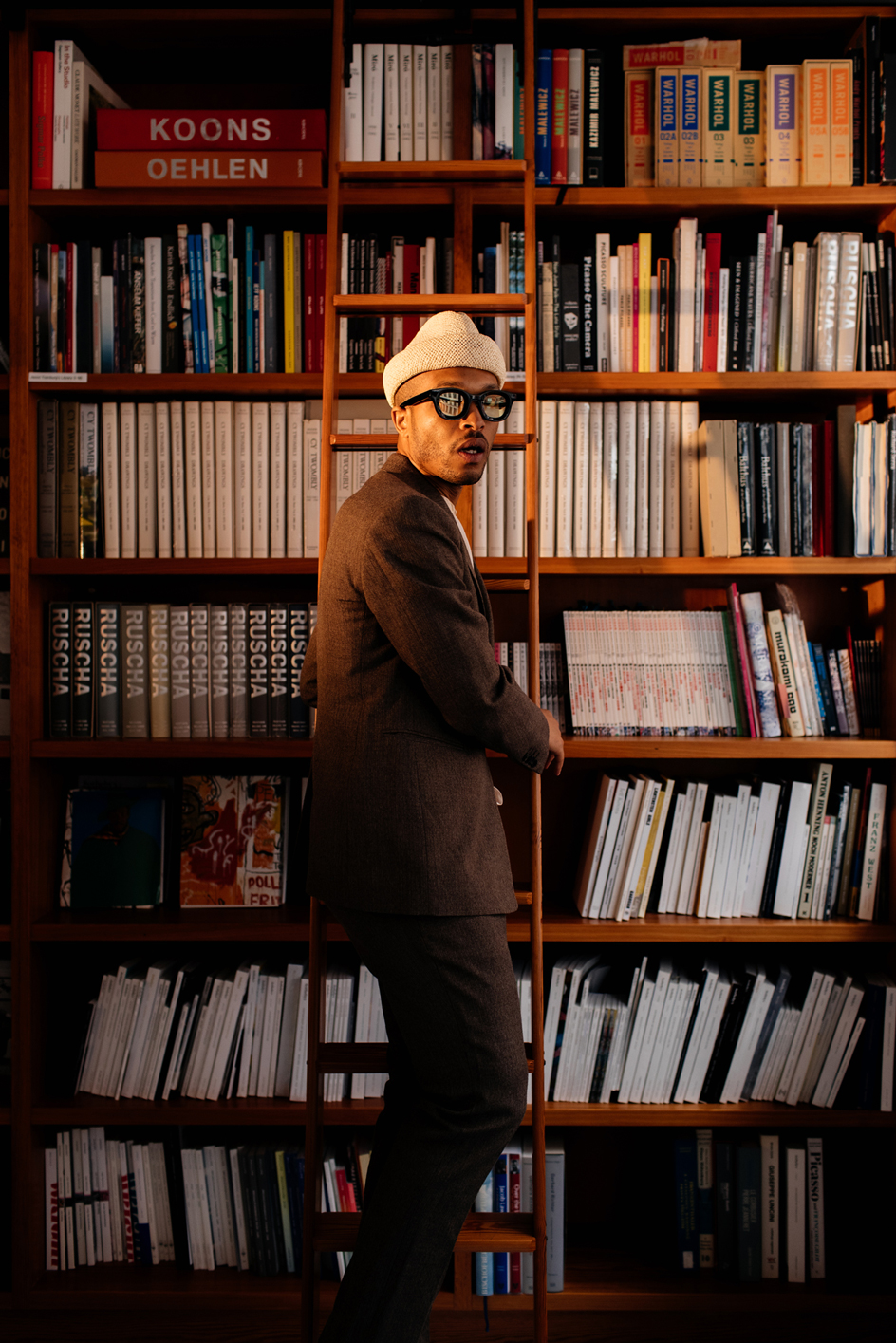

Curator Antwaun Sargent at Gagosian’s 555 West 24th Street location in New York.

Outside of his published writing – pieces for The New York Times, The New Yorker, and Interview, to name a few, plus two books, The New Black Vanguard (accompanied by an exhibition at the Aperture Foundation) and Young, Gifted and Black: A New Generation of Artists – Sargent has also helped shape the art world in subtler ways. He is known for engaging in conversations over messages and group chats with artists and curators, friends and foes alike, and in Facebook battles, where he rarely has the first word but often the last. In these channels, he has tackled Black agency, moral responsibility within representation and presentation, and the eternal question of formal artistic merit.

Sargent is forthright, unafraid of failure, and constantly assessing and reassessing his practice and point of view. This pattern of self-regulation and self-education influences the products of his labour in many ways. In the case of his Gagosian show, his work ethic and perspective are evident in a curatorial prompt that is both ephemeral and solid.

‘Social Works’ balances its star-studded roster with emerging and mid-career talents. Among them are members of NXTHVN, the arts incubator founded by Titus Kaphar, Jason Price and Jonathan Brand, whose works reflect varied practices, backgrounds and concerns: Allana Clarke is currently working through the NXTHVN fellowship, while Alexandria Smith, Zalika Azim, Kenturah Davis and Christie Neptune are all 2019 studio alumni. Bridging the gap between the NXTHVN cohort and household names such as Theaster Gates or Carrie Mae Weems, are artists including Lauren Halsey, a trained architect whose family has resided in South Central Los Angeles for generations. She mines personal memories and local history, reshuffling realities to imagine possible futures. Site-specific sculptures play a central role in her practice: sometimes monochromatic, sometimes bursting with colour, they harness found, reworked or finely fabricated materials, consuming the viewer’s every sense. On social media, she names her vision #FUBUarchitecture, after FUBU (For Us, by Us), a Black streetwear brand that shot to fame in the 1990s.

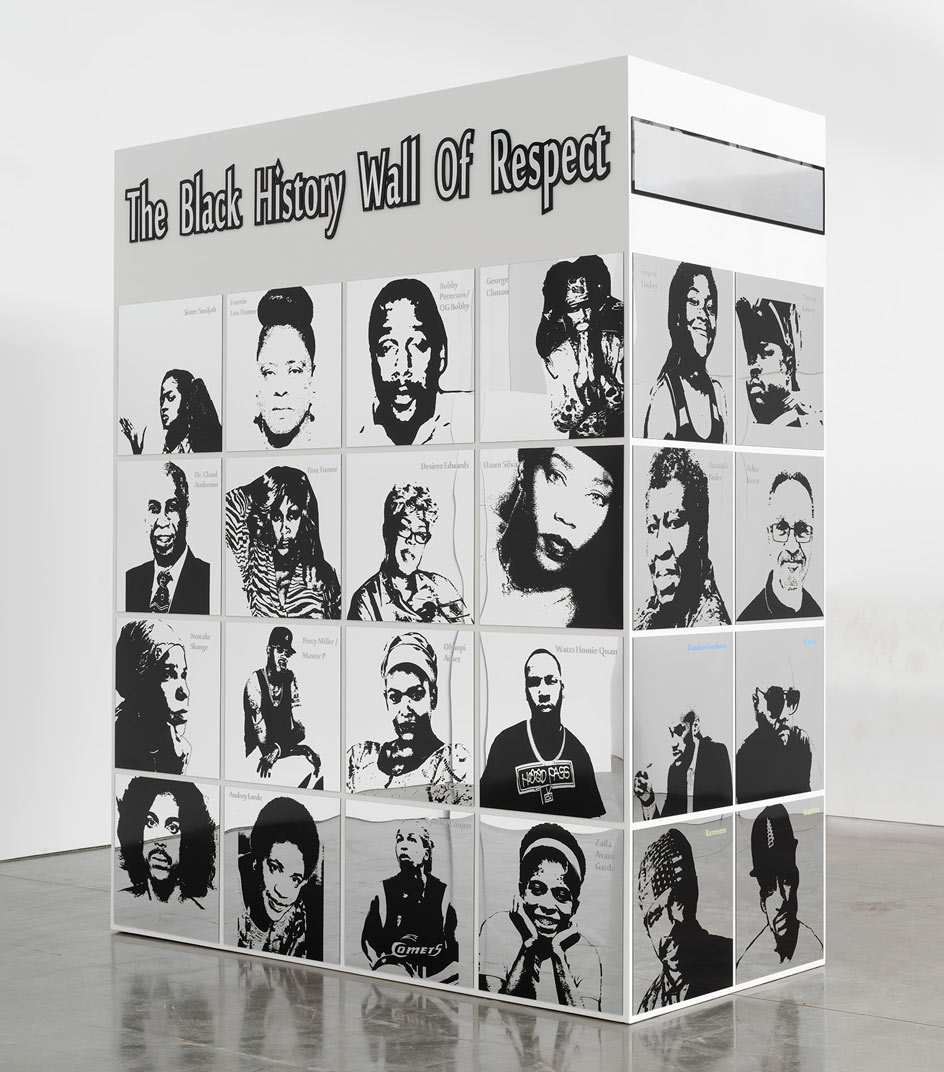

Lauren Halsey, black history wall of respect (II), 2021, Vinyl, acrylic, and mirror on wood. © Lauren Halsey. Courtesy of the artist, David Kordansky Gallery, and Gagosian

In her ‘box’ sculptures, Halsey assembles brightly-hued acrylic cuboids on top of each other, embellishing them with grafitti-like messaging, and elements from discarded and nostalgic signage – honouring the streets of her storied neighbourhood, as well as the life force held within it. In other works, she uses synthetic hair, gypsum, wood (which she carves by hand), foam, carpet and cement to create Afrofuturist potentialities that zing with the urgency of a Black woman who knows that civic change is the only option.

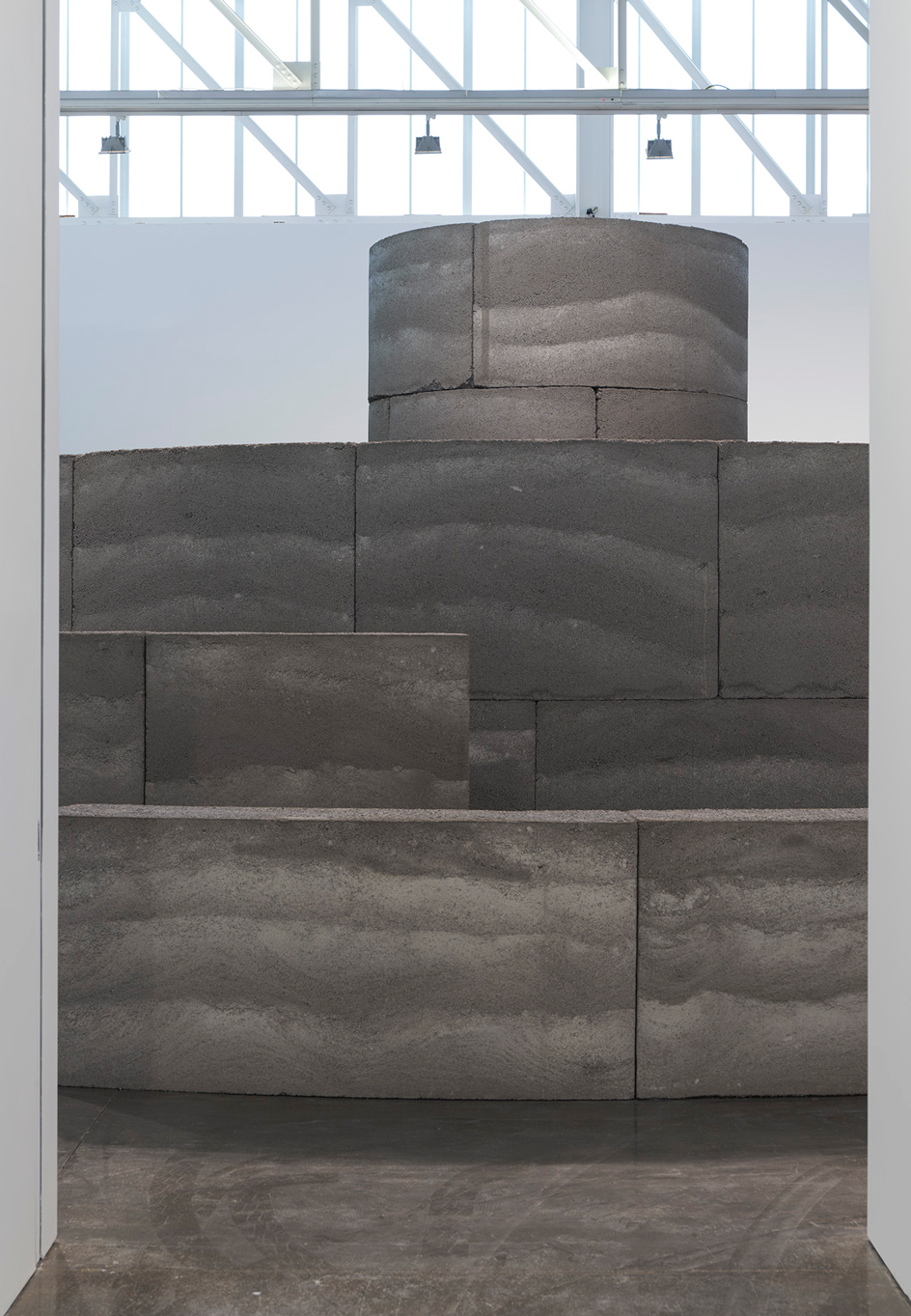

Another highlight of the exhibition is a contribution from David Adjaye, an architect with deep ties to the art world. Best known in the US for his National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington DC, he also designed Lorna Simpson’s Brooklyn studio (see W*228) and the 2012 exhibition ‘Richard Avedon: Murals & Portraits’ at Gagosian New York. Varied though his practice is, rarely does Adjaye embark on entirely non-functional projects. ‘I interviewed David for Interview magazine in 2015, focusing on architecture,’ recalls Sargent. ‘For “Social Works”, Adjaye has created his first piece of large-scale sculpture, which will also be the first piece of fine art that he’s shown in the States.’ The monumental work is made from compacted earth, which Sargent sees as ‘a call to reconsider the value of certain materials’. It dovetails materially with the architect’s plans for the Edo Museum of West African Art, in Benin City, Nigeria, home to one of the oldest kingdoms in the world. Intended to house the Benin Bronzes upon their return to Africa, the museum project also entails an excavation of its site to uncover ancient architectural remnants.

Carrie Mae Weems, The British Museum, 2006–Digital c-print. Edition of 5 + 2 AP. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York and Gagosian

Another seasoned artist, Carrie Mae Weems, is represented by photographs from her ongoing series Roaming and Museums (which began in 2006), in which she stands in, or in front of, museums, well-known streets and ‘architectural wonders’, directly confronting the inclusivity (or lack thereof) of these supposedly public spaces. She wears an elegant but nondescript black dress, highlighting her regal form, planting her within each image like a Greek caryatid, immovable and required for the support and continuance of a structure.

Linda Goode Bryant, who is creating an interactive work for the show, has been a fixture in New York’s art and activism circles for the last 50 years, founding New York’s first Black-run gallery, Just Above Midtown, in 1974. Bryant’s non-linear trajectory has included filmmaking, farming and entrepreneurship. For ‘Social Works’ she drew inspiration from her work with Project Eats, the urban farming venture she started in 2009, to create a living sculpture, Are we really that different. Made in collaboration with architect Liz Diller, it will grow and provide food for gallery visitors free of charge – a first for Gagosian.

Rick Lowe founded the non-profit Project Row Houses in 1993 to house and inspire the Black community of Houston’s Third Ward neighbourhood, providing a case study and format for creative, economically-engaged, collective healing. He will show pieces from his Black Wall Street series. ‘The series is an extension of the social work I do. It is an investigation into the economic plight of African Americans, manifested in an abstract form,’ explains the artist, whose work defies the white, mainstream custom (both within historical and contemporary social and economic contexts) to only represent Black people in wholly inaccurate, negative ways that are uninspiring and unhelpful to the Black community.

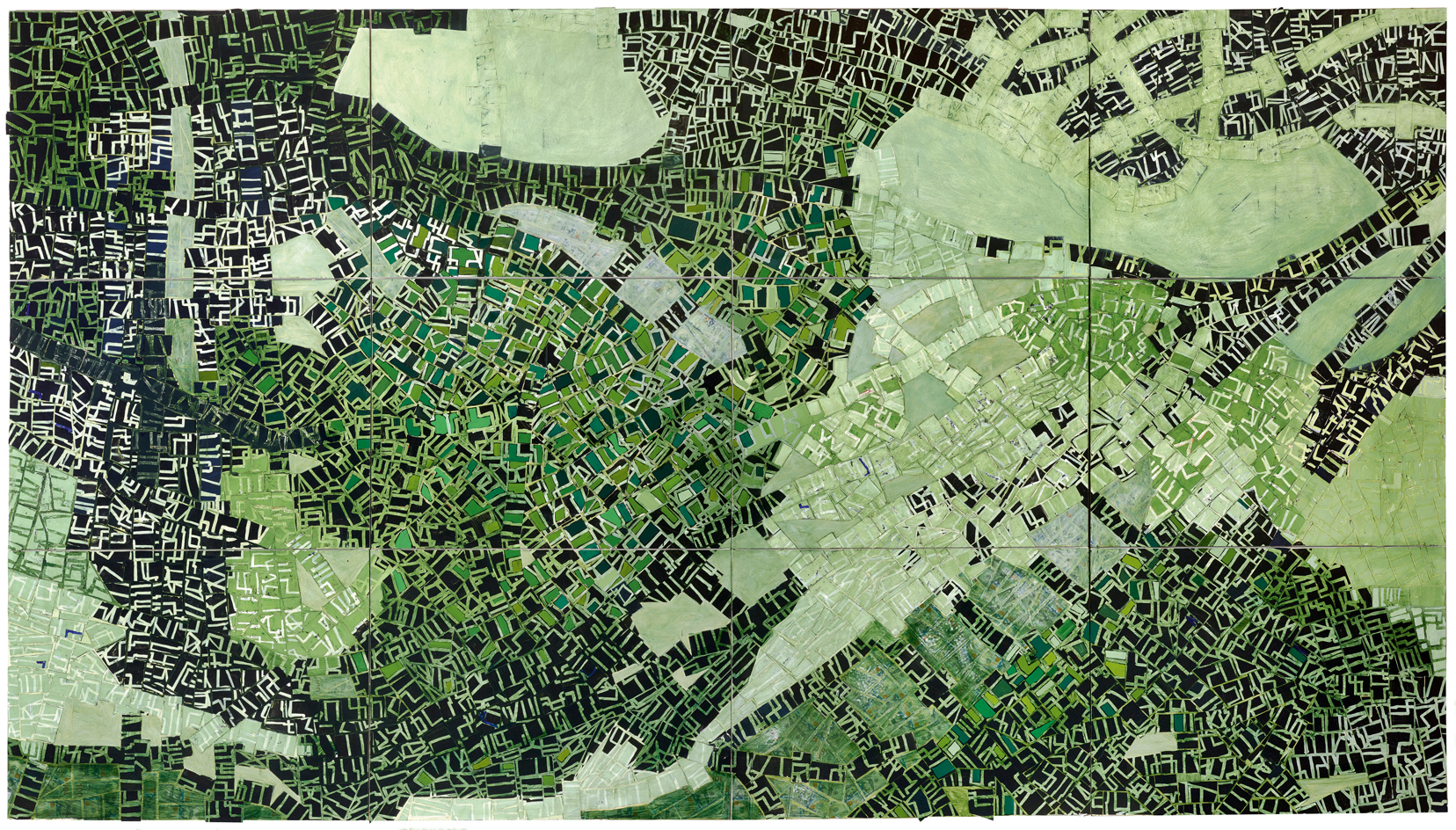

Rick Lowe, Black Wall Street Journey #5, (2021) is an acrylic and paper collage on canvas measuring 274.3 x 487.7cm, part of a series inspired by the burning down of a prosperous Black neighbourhood in Oklahoma in 1921. © Rick Lowe Studio, courtesy of the artist and Gagosian

Particularly, Lowe has engaged with the history of Greenwood, a prosperous neighbourhood in Tulsa, Oklahoma, which was known as ‘Black Wall Street’ in the early 20th century, and similar bursts of economic progress in Durham, North Carolina and Richmond, Virginia. ‘The Black Wall Street journey was threatening to mainstream society, which is why the burning of Greenwood happened,’ says Lowe, referring to the 1921 massacre and destruction of the economically successful and independent African American community in Greenwood, by nearby white communities and the KKK, who colluded with the US government.

The Black Wall Street series is an extension of the social work I do; it’s an investigation into the economic plight of African Americans

Rick Lowe

In the 1990s, Lowe led a group of artists who purchased, gutted and renovated a series of 1930s shotgun houses in Houston’s Third Ward, with limited financial resources and calling on helping hands within their community. Now, nearly 30 years on, Project Row Houses serves as an example of what can be built and sustained independently within the Black community with no external aid, subtly echoing Halsey’s ‘FUBU’ sentiment. ‘That’s one of the vital steps towards economic emancipation, understanding the value that we as Black people have and being able to access it and cash in on it,’ says Lowe. Sargent’s choice to show works by such established social excavators alongside those of the younger artists Alexandria Smith and Christie Neptune exemplifies his ability to colour outside the lines, while maintaining a tight curatorial premise.

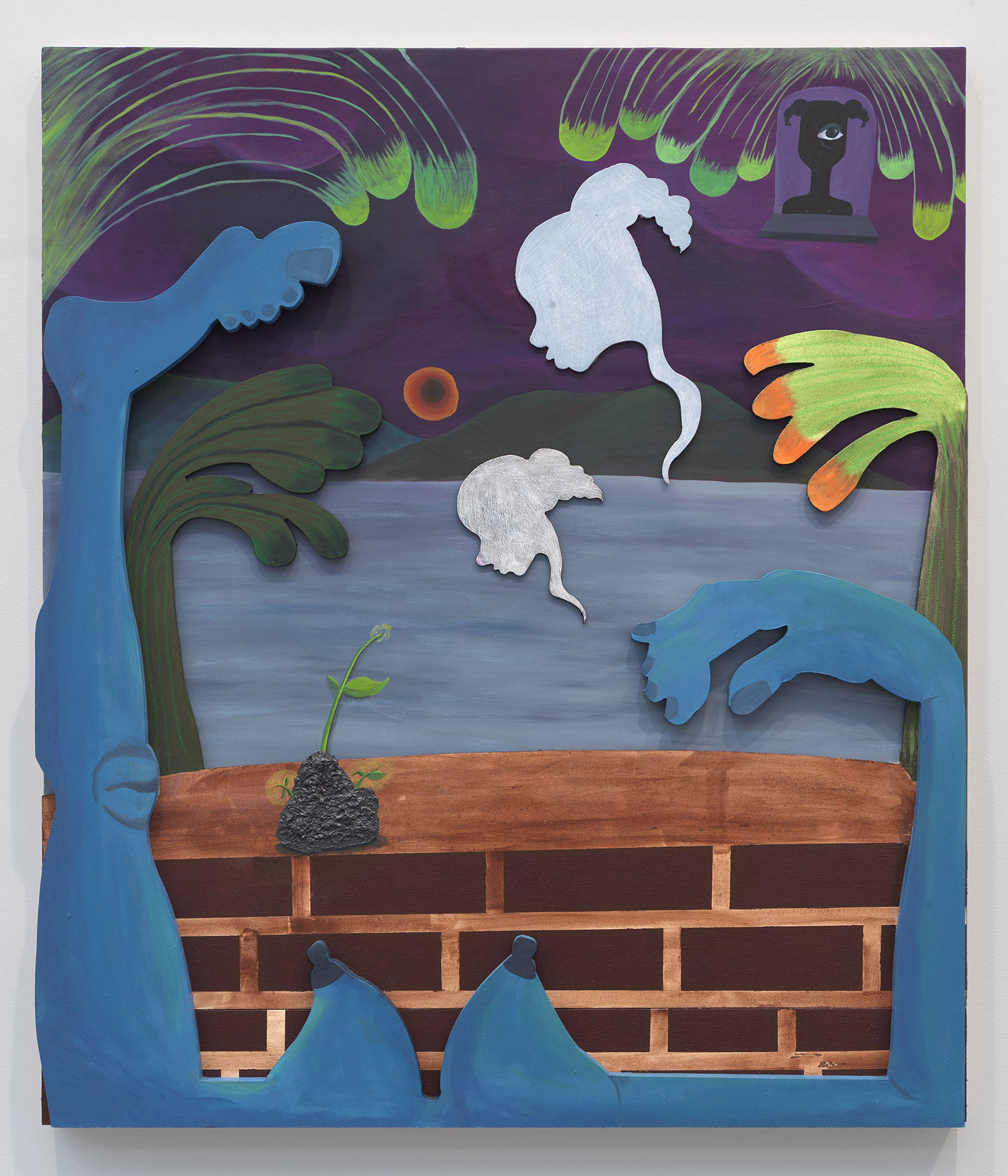

Alexandria Smith, Iterations of a galaxy beyond the pedestal, 2021, mixed media on three-dimensional wood assemblage. © Alexandria Smith. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian

Smith, who has been head of the painting programme at London’s Royal College of Art since 2019, has produced work from the moment she could pick up a pen (or crayon). ‘My mother says that I have been calling myself an artist since I was three.’ She works in oil and acrylic, slicing and adding layers to create scenes somewhere between reality and a dream. Her figures, erroneously referred to as grotesque by white critics and curators, are embodiments of the queer, Black, female experience the artist inhabits. Limbs and halved gestures appear independent of full-body forms, a collage in themselves, beckoning the viewer’s attention.

Neptune, who is presenting a piece from her ongoing series Constructs and Context Relativity, is also an educator, albeit of elementary school students. Before, between and after lessons, Neptune pieces together her students’ experiences and queries to inform her work. ‘Most of the ideas I have for my projects come from my class,’ says the artist. ‘I make the work and try to live it by teaching it, but also by creating spaces for younger adults to discuss it and actualise it.’

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

A still from Christie Neptune’s Constructs and Context Relativity – Performance II (2021), a three-channel HD video and Super 8mm transfer (4:3 ratio), exploring space and social constructs. courtesy of the artist, Grant Wahlquist Gallery, Portland, Maine, and Gagosian

In Constructs and Context Relativity – Performance II (2021), Neptune explores relational theories of space, social politics and her own internal experiences. ‘When conceptualising a work, I look at the space in which we live – social constructs that don’t have the semblance of physicality in them, but are still very real.’ The work is a mental voyage, occupying space with the same logic and form as a tesseract. Space is not the artist’s only concern though. Time also takes centre stage, with the work of the Italian futurists providing intellectual fodder.

Most of the ideas I have for my projects come from my elementary school students. I make the work and try to live it by teaching it

Christie Neptune

The bringing together of such a varied group, in terms of age, medium and form, is characteristic of Sargent’s ambition. Neptune, who is 35, speaks of age affording her another level of nuance, her past and present selves melding to create more expansive work. The same could be said for the show in its entirety – Sargent has brought together artists at every stage of their career, with differing but interconnected stories, all ripe for discussion, serving as the perfect catalysts for introspection and its logical follower, change. The works on view come together to create the many-sided structure of the Black American experience, with its endless facets, offering individual and meaningful vantage points. The show belongs to these artists, but it is also a real testament to Sargent’s breadth as a thinker.

Few contemporary figures are as agile in their navigation of a both perilous and still largely stodgy art world. In an early adulthood dedicated to education and discovery, Sargent has cultivated a fearlessly non-traditional approach, which has proven wildly addictive to the art world elite. His jagged ascent, including a stint teaching kindergarten, writing catalogues for Arthur Jafa and Mickalene Thomas, and giving a TEDx Talk on Art and the #blacklivesmatter Revolution, reveals the success that can come from the right cocktail of determination, analytical rigour, and a willingness to fumble about. And that success is now on view for the benefit of any willing and able visitor.

'Social Works' installation View, 2021. Courtesy Gagosian

Allana Clarke, There Was Nothing Left For Us, 2021, 30 second hair bonding glue, rubber latex, and carbon dye. © Allana Clarke. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian

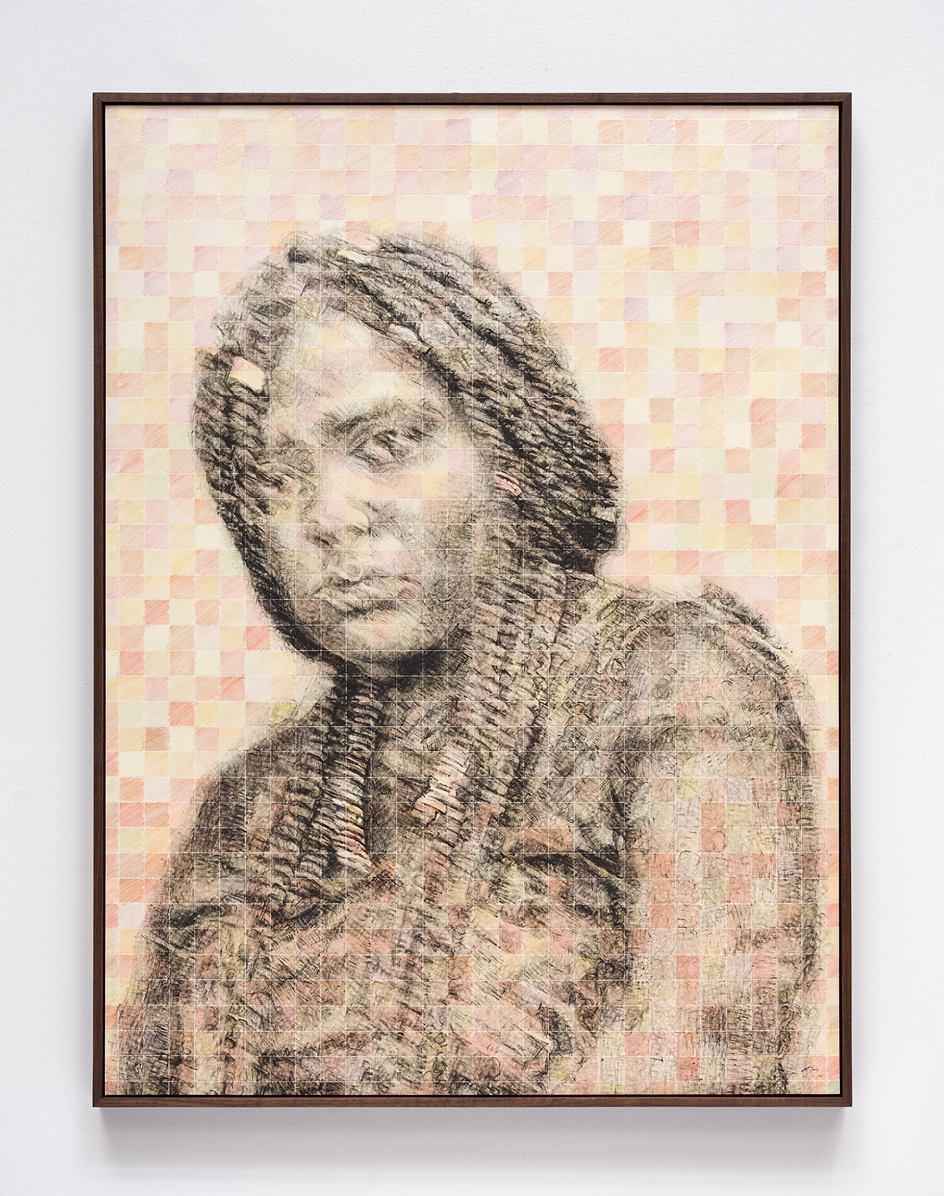

Kenturah Davis, the bodily effect of a color (sam), 2021, oil paint applied with rubber stamp letters and color pencil on debossed Igarashi Kozo paper, in artist's frame. © Kenturah Davis. Courtesy of the artist, Matthew Brown Los Angeles, and Gagosian

'Social Works' installation View, 2021. Courtesy Gagosian

Zalika Azim, Heard on higher grounds (the hunted have two primary tools for survival: imagination and hyperbole), 2021. C-print mounted on archival pigment print. Courtesy Gagosian

'Social Works' installation View, 2021. Courtesy Gagosian

Are we really that different, a fully operational urban farm by Linda Goode Bryant in collaboration with architects Diller Scofidio + Renfro.

INFORMATION

‘Social Works’, until 13 August, Gagosian, 555 West 24th Street, New York. gagosian.com

-

Extreme Cashmere reimagines retail with its new Amsterdam store: ‘You want to take your shoes off and stay’

Extreme Cashmere reimagines retail with its new Amsterdam store: ‘You want to take your shoes off and stay’Wallpaper* takes a tour of Extreme Cashmere’s new Amsterdam store, a space which reflects the label’s famed hospitality and unconventional approach to knitwear

By Jack Moss

-

Titanium watches are strong, light and enduring: here are some of the best

Titanium watches are strong, light and enduring: here are some of the bestBrands including Bremont, Christopher Ward and Grand Seiko are exploring the possibilities of titanium watches

By Chris Hall

-

Warp Records announces its first event in over a decade at the Barbican

Warp Records announces its first event in over a decade at the Barbican‘A Warp Happening,' landing 14 June, is guaranteed to be an epic day out

By Tianna Williams

-

Leonard Baby's paintings reflect on his fundamentalist upbringing, a decade after he left the church

Leonard Baby's paintings reflect on his fundamentalist upbringing, a decade after he left the churchThe American artist considers depression and the suppressed queerness of his childhood in a series of intensely personal paintings, on show at Half Gallery, New York

By Orla Brennan

-

Desert X 2025 review: a new American dream grows in the Coachella Valley

Desert X 2025 review: a new American dream grows in the Coachella ValleyWill Jennings reports from the epic California art festival. Here are the highlights

By Will Jennings

-

This rainbow-coloured flower show was inspired by Luis Barragán's architecture

This rainbow-coloured flower show was inspired by Luis Barragán's architectureModernism shows off its flowery side at the New York Botanical Garden's annual orchid show.

By Tianna Williams

-

‘Psychedelic art palace’ Meow Wolf is coming to New York

‘Psychedelic art palace’ Meow Wolf is coming to New YorkThe ultimate immersive exhibition, which combines art and theatre in its surreal shows, is opening a seventh outpost in The Seaport neighbourhood

By Anna Solomon

-

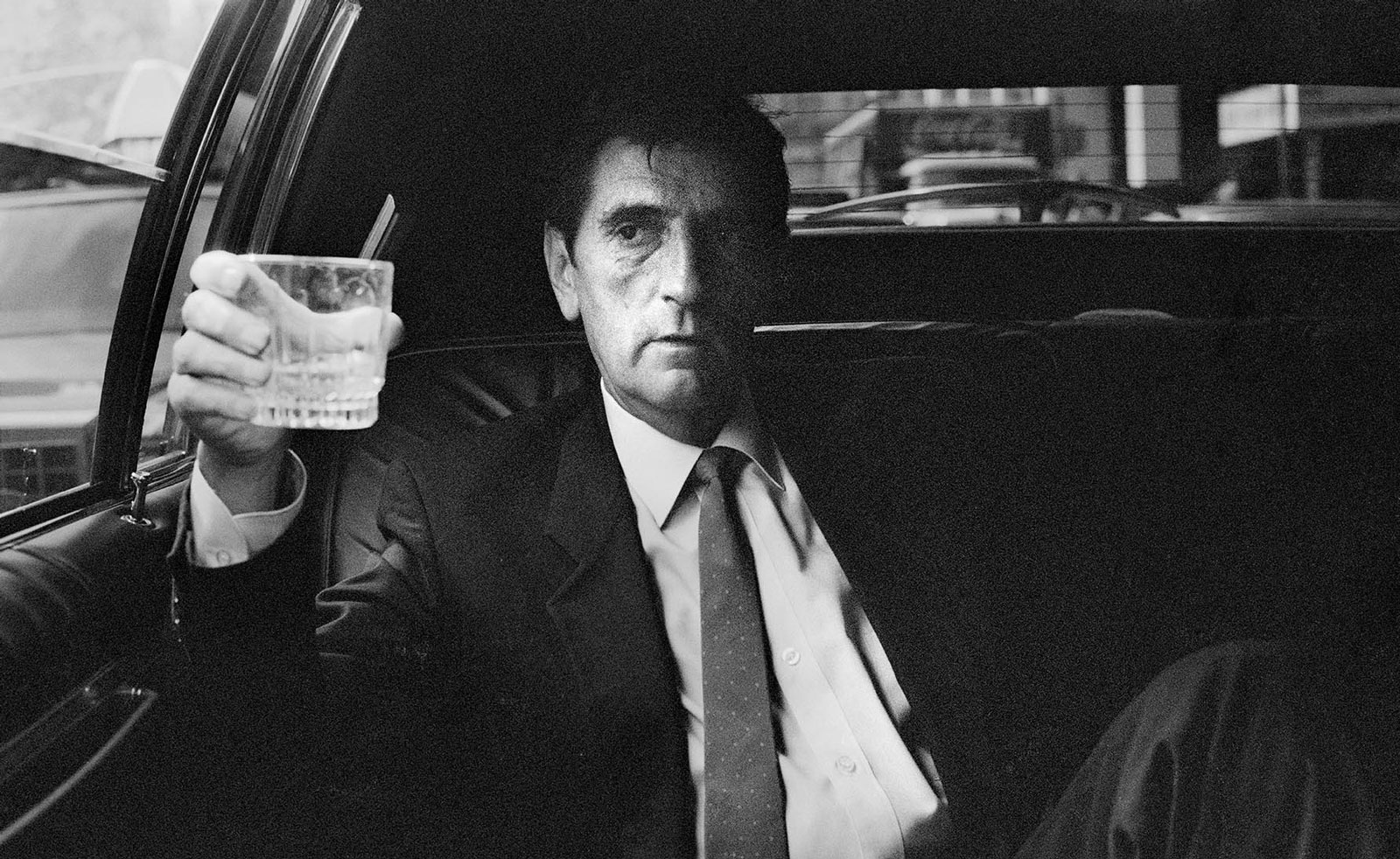

Wim Wenders’ photographs of moody Americana capture the themes in the director’s iconic films

Wim Wenders’ photographs of moody Americana capture the themes in the director’s iconic films'Driving without a destination is my greatest passion,' says Wenders. whose new exhibition has opened in New York’s Howard Greenberg Gallery

By Osman Can Yerebakan

-

20 years on, ‘The Gates’ makes a digital return to Central Park

20 years on, ‘The Gates’ makes a digital return to Central ParkThe 2005 installation ‘The Gates’ by Christo and Jeanne-Claude marks its 20th anniversary with a digital comeback, relived through the lens of your phone

By Tianna Williams

-

In ‘The Last Showgirl’, nostalgia is a drug like any other

In ‘The Last Showgirl’, nostalgia is a drug like any otherGia Coppola takes us to Las Vegas after the party has ended in new film starring Pamela Anderson, The Last Showgirl

By Billie Walker

-

‘American Photography’: centuries-spanning show reveals timely truths

‘American Photography’: centuries-spanning show reveals timely truthsAt the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, Europe’s first major survey of American photography reveals the contradictions and complexities that have long defined this world superpower

By Daisy Woodward