Art, science, and activism coalesce in ‘Thus waves come in pairs’ at Ocean Space, Venice

‘Thus waves come in pairs’, an exhibition of two new commissions at Ocean Space in Venice, features potent work by Simone Fattal, and artist duo Petrit Halilaj & Álvaro Urbano

Creatures assembled from narrow Venetian passages surrounding the square facing the church of Saint Lorenzo. Merrily dancing in a circle around the well, each emitting a unique sound, their noises found rhythm and conversation within joyful congregation. A distant sound, like the call of a whale, came from beyond the imposing church doors, before two enormous seagulls emerged from the building, corralling and encouraging the dancing critters inside.

These creatures are not of the lagoon, but the imagination of artist duo Petrit Halilaj & Álvaro Urbano. Their work Lunar Ensemble for Uprising Seas, co-commissioned by Audemars Piguet Contemporary and arts organisation TBA21–Academy, is one of two installations split across the vertiginous, long-deconsecrated church that is now Ocean Space, home of TBA21–Academy. Before it was revealed that the two seagulls were, in fact, the artists in costume, the pair observed their sculptures in the space as performers played each piece as an instrument, together in an unlikely ensemble.

Petrit Halilaj and Álvaro Urbano, ‘Lunar Ensemble for Uprising Seas’, 2023. Exhibition view of ‘Thus waves come in pairs’, Ocean Space, Venice

As sculptures, the 40-plus imaginary aluminium animals represent non-human lifeforms coming together in choreography and solidarity, inspired by a Spanish song ‘Ay mi pescadito,’ telling of young fish studying survival and belonging at the bottom of the sea. The creatures represent queer and unorthodox human and non-human existences, expressing the importance of ecosystems across identities, however submerged beneath the glistening surface of fixed conventions and heteronormativity.

As instruments, the works create often beautiful and haunting sounds. Plucked, bowed, and blown, the sounds fill the space, the audience following reverberating notes up into the heights of Ocean Space. As Venetian light filters into the monochrome architecture, a feeling that we are looking up towards the sea’s surface from a seabed is palpable – even the walls exposed brickwork at lower levels, where flooding waters have removed historic plaster, read as a subaquatic landscape.

Petrit Halilaj and Álvaro Urbano, Lunar Ensemble for Uprising Seas, 2023. Exhibition view of ‘Thus waves come in pairs’, Ocean Space, Venice

‘It’s a meeting in a church, but also meeting a church,’ Halilaj contributes, Urbano adding that ‘the former church is a music box, the space has such resonance’. In fact, the acoustics and quality of sound that led to their sonic intervention has heritage, it is said that Vivaldi rehearsed there for a similar, emotive sense of space. There are other ghosts in the architecture – Marco Polo is apparently buried in the church, which stood before the current 16th-century reconstruction; some suspect he is still buried somewhere, deep in mortar, brickwork, and mass. He has been hunted for, but some stories are too deep to be found.

In his books on travels, Marco Polo discussed the fishing of pearls in India and Ceylon, describing how divers spend all day repeatedly descending to the seabed to fill body-strapped nets with sea oysters. In the other half of Ocean Space, divided by a grand three-bay screen and the double-sided altar, sit seven perfectly formed pink spheres, as if pearls dropped by a diver silently waiting to be discovered here at the bottom of this imagined ocean. They are part of an installation by Simone Fattal, Sempre il mare, uomo libero, amerai! (Free man, you’ll love the ocean endlessly!), the title drawn from Charles Baudelaire’s poem ‘The Man and the Sea’.

Simone Fattal, Sempre il mare, uomo libero, amerai!, 2023. Exhibition views of ‘Thus waves come in pairs’, Ocean Space, Venice

Near the pearls stand two glass abstracted figures, Máyya and Ghaylán. Two lovers celebrated in Islamic folklore and poetry, both had flotillas working in the pearl trade. Máyya’s were faster until Ghaylán, observing a firefly’s wings, added sails to his fleet. This competition was between lovers but also runs through capitalism and the history of trade, often brutally – Fattal speaks of Western colonialism as a violent act to break Venice’s monopoly of trade through the Orient to India. Another sculpture, made of earthenware, resembles the wooden poles dotting Venice’s lagoon, safely guiding boats. But here, if we take the floor as our seabed, they are also drowned, and any guidance they once offered, now lost.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Fattal is not only an artist but also a translator and publisher, though ‘I am first and foremost a reader,’ she says. Here, her work is saturated with literary references beyond Baudelaire. There are not many works, but they have a presence which does do not get lost within Ocean Space’s depths, the volume of conjured resonances adding to their volume. As I look at the pearls I think of Homer, ‘The liquid drops of tears that you have shed, Shall come again transformed in Orient pearls’; Robert Wyatt, ‘With all the will in the world, Diving for dear life, When we could be diving for pearls’; and Thoman Mann’s description of Tadzio’s mother in Death in Venice, ‘there was something faintly fabulous … in her appearance, though lent solely by the pearls she wore.’

Simone Fattal, Sempre il mare, uomo libero, amerai!, 2023. Exhibition views of ‘Thus waves come in pairs’, Ocean Space, Venice

The trade-in pearls were, Fattal says, ‘the connection between the Orient and Europe’. In the global now, we have removed all trace of such nuanced histories, in part due to Venice itself. Pearls are timeless, seen around the neck of Persian princesses as well as Love Island hunks, 2,400 years later. Those Marco Polo wrote of were irregular, non-spherical, and rare but today, they are uniform and perfect. Venice’s glassworks had long crafted artificial pearls, but as Renaissance demand grew, production multiplied, with cheaper Venetian lacquered glass faux-pearls traded around the world. Today, most pearls are farmed or faux, their Oriental connection transformed into a manufactured tradeable aesthetic, inherent truths and historic meaning saturated in capitalist values, but still powerful.

‘Baudelaire was my companion for years – and still is,’ Fattal says after reading ‘The Man and the Sea’ in the original French at the exhibition opening. A line of it resonates with both installations sitting on the seabed of Ocean Space, and how each project seeks to reveal hidden narratives and meanings subsumed under the surface of modern global existence: ‘Oh, sea, no one knows the riches of your keep, so jealously you guard your secrets.’

Simone Fattal, Sempre il mare, uomo libero, amerai!, 2023. Exhibition views of ‘Thus waves come in pairs’, Ocean Space, Venice

Lunar Ensemble for Uprising Seas, performance by Petrit Halilaj and Álvaro Urbano, 21 April 2023 at Ocean Space, Venice

Lunar Ensemble for Uprising Seas, performance by Petrit Halilaj and Álvaro Urbano, 21 April 2023 at Ocean Space, Venice

‘Thus waves come in pairs’, until 5 November 2023. tba21.org

Will Jennings is a writer, educator and artist based in London and is a regular contributor to Wallpaper*. Will is interested in how arts and architectures intersect and is editor of online arts and architecture writing platform recessed.space and director of the charity Hypha Studios, as well as a member of the Association of International Art Critics.

-

Extreme Cashmere reimagines retail with its new Amsterdam store: ‘You want to take your shoes off and stay’

Extreme Cashmere reimagines retail with its new Amsterdam store: ‘You want to take your shoes off and stay’Wallpaper* takes a tour of Extreme Cashmere’s new Amsterdam store, a space which reflects the label’s famed hospitality and unconventional approach to knitwear

By Jack Moss

-

Titanium watches are strong, light and enduring: here are some of the best

Titanium watches are strong, light and enduring: here are some of the bestBrands including Bremont, Christopher Ward and Grand Seiko are exploring the possibilities of titanium watches

By Chris Hall

-

Warp Records announces its first event in over a decade at the Barbican

Warp Records announces its first event in over a decade at the Barbican‘A Warp Happening,' landing 14 June, is guaranteed to be an epic day out

By Tianna Williams

-

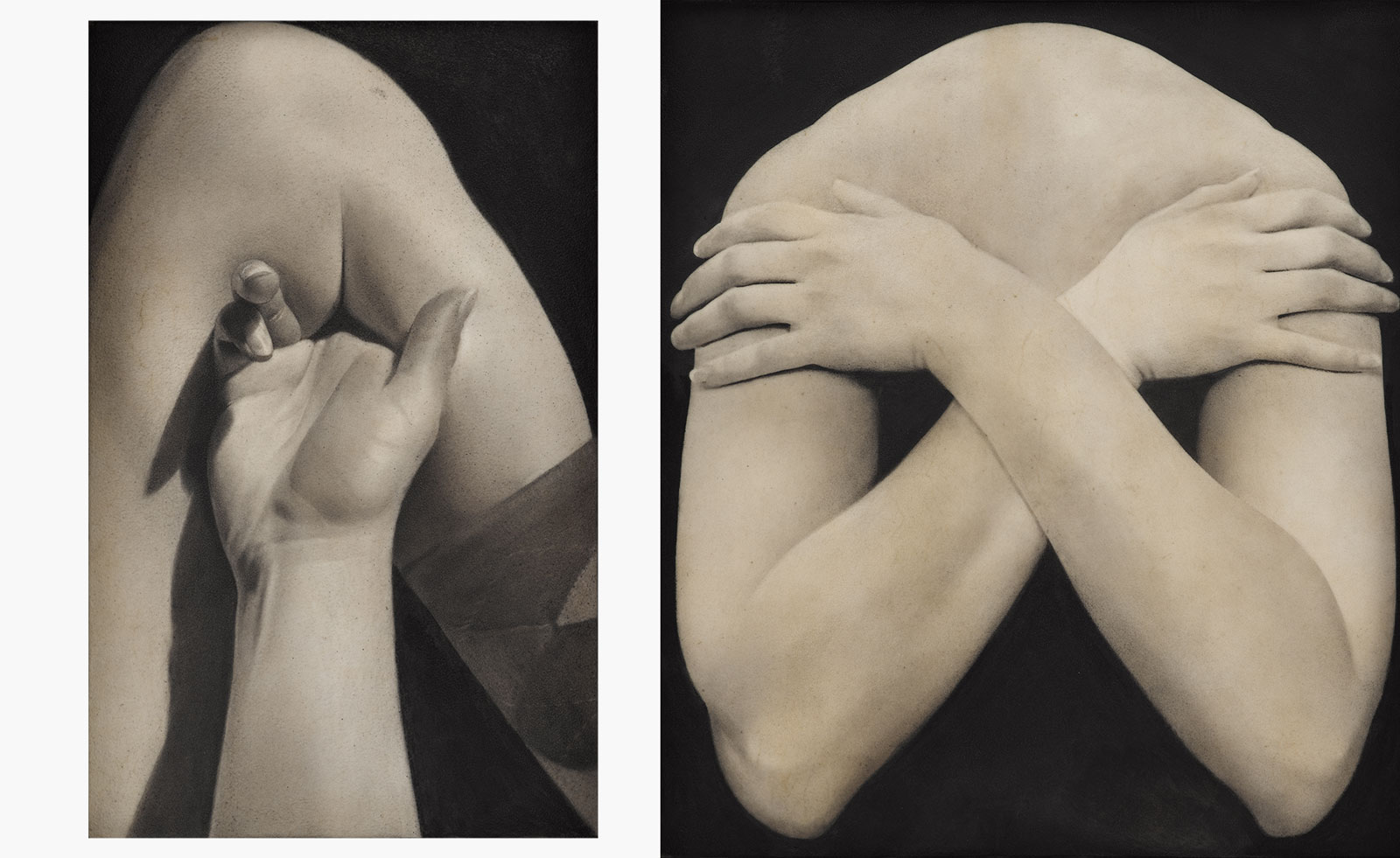

Saskia Colwell’s playful drawings resemble marble sculptures

Saskia Colwell’s playful drawings resemble marble sculpturesSaskia Colwell draws on classical and modern references for ‘Skin on Skin’, her solo exhibition at Victoria Miro, Venice

By Millie Walton

-

Portrait of a modernist maverick: last chance to see the Jean Cocteau retrospective in Venice

Portrait of a modernist maverick: last chance to see the Jean Cocteau retrospective in Venice‘Cocteau: The Juggler’s Revenge’, celebrating the French artist's defiance of artistic labels, is in its final week at Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice

By Caragh McKay

-

‘Personal Structures’ in Venice is about ‘artists breaking free’

‘Personal Structures’ in Venice is about ‘artists breaking free’‘Personal Structures 2024: Beyond Boundaries’ reveals a rich tapestry of perspectives on the challenges of our time, from culture to climate and identity

By Nargess Banks

-

Aindrea Emelife on bringing the Nigerian Pavilion to life at the Venice Biennale 2024

Aindrea Emelife on bringing the Nigerian Pavilion to life at the Venice Biennale 2024Curator Aindrea Emelife has spearheaded a new wave of contemporary artists at the Venice Biennale’s second-ever Nigerian Pavilion. Here, she talks about what the world needs to learn about African art

By Ugonna-Ora Owoh

-

Kapwani Kiwanga considers value and commerce for the Canada Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2024

Kapwani Kiwanga considers value and commerce for the Canada Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2024Kapwani Kiwanga draws on her experiences in materiality for the Canada Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale

By Hannah Silver

-

Venice Art Biennale 2024 highlights

Venice Art Biennale 2024 highlightsThe Venice Art Biennale took place 20 April - 24 November 2024 – here are our highlights from around Venice

By Amah-Rose Abrams

-

What’s the big deal with breasts, ask artists at the Venice Biennale

What’s the big deal with breasts, ask artists at the Venice Biennale‘Breasts’ is set to open at ACP Palazzo Franchetti for the duration of the Venice Art Biennale 2024

By Hannah Silver

-

Art X Lagos 2023: discover the artists to watch

Art X Lagos 2023: discover the artists to watchArt X Lagos 2023, the 8th edition of West Africa’s biggest art fair, was bigger and better than ever

By Ugonna-Ora Owoh