Artist Sophie Calle on love, loss and 125 years of lonely hearts ads

French artist Sophie Calle’s work spans imagined lives and actual death. Here, she talks about exhibitionism and intimacies, love and loss, and more than a century’s worth of lonely hearts ads that inspired her latest project and a 20-page portfolio for Wallpaper's November 2020 issue

It is a stiflingly hot day in August, and Sophie Calle is wearing a flowered dress and tinted eyeglasses, listening to Bob Dylan’s latest album in a loft-like space she calls ‘my church’. The house is a former chapel in the Camargue, the wild region of southern France where the artist has spent summers throughout her life. A zebra bursts from the wall above the door, part of her large taxidermy collection, each animal named after a different friend (the zebra is Daniel, as in Buren, a French artist renowned for his work with stripes). Another wall features an assortment of art pieces by Calle and others, including, framed in silver lettering, the word ‘souci’ (‘worry’), the last thing her mother said. Abandoned tombstones decorate the garden.

Calle, 67, has become one of France’s most important contemporary artists by using her own life and the imagined lives of others as subject matter. Her books and exhibitions combine photos or video with text, exploring such themes as absence, death, suffering and desire. She does not hesitate to break taboos, overstep boundaries, or invite viewers to share in the discomfort (or guilty pleasure) of voyeurism. Even when the content is mundane, the works are provocative and compelling. They can be surprisingly touching, and just as surprisingly funny.

Calle photographed on 15 September 2020 at home in Malakoff, on the south-west outskirts of Paris. Photography: Alexandre Guirkinger

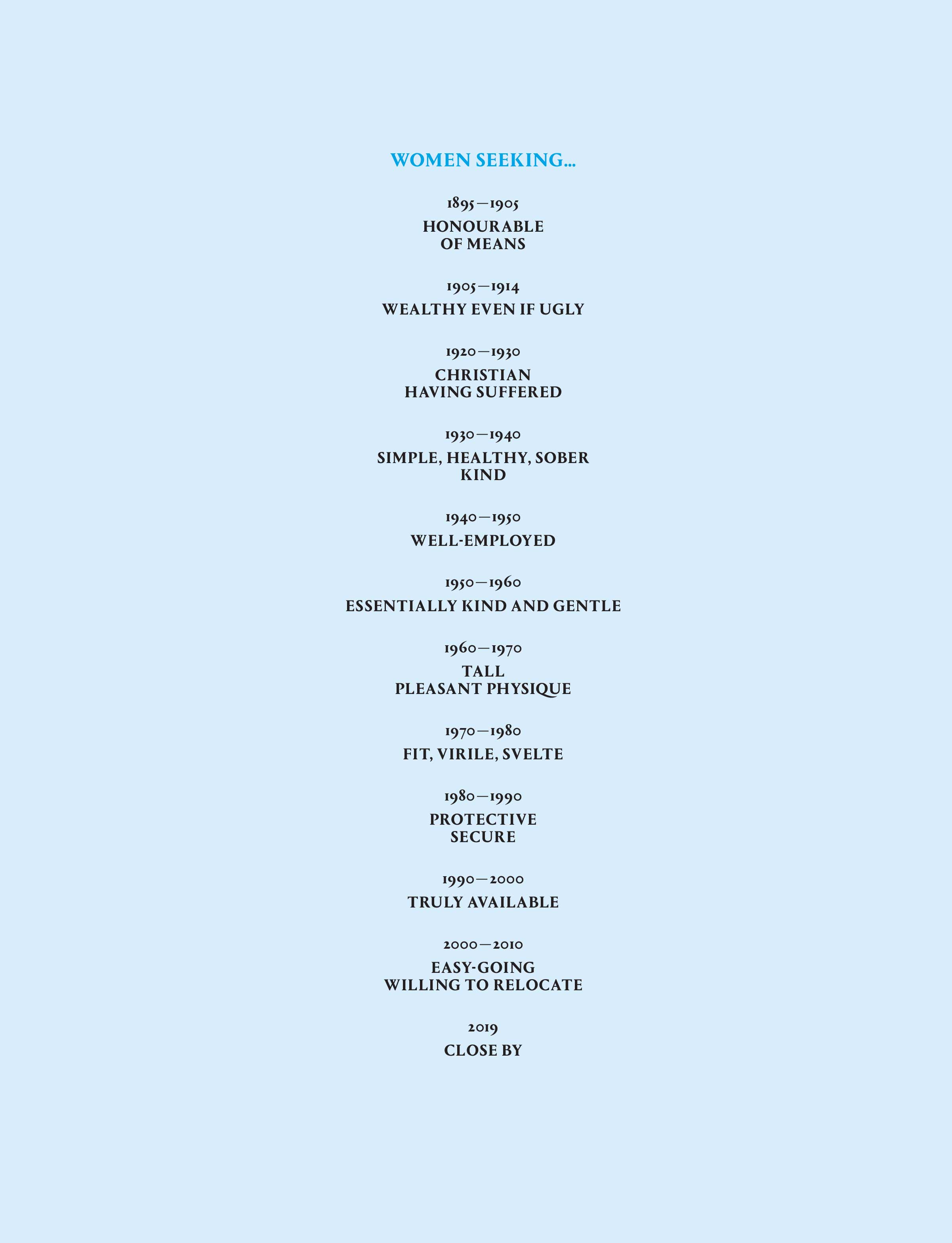

The day before we meet, Calle has taken her camera into the Camargue to shoot hunting watchtowers for her ongoing project, A l’Affût (‘On the Hunt’). The related book, Sans Lui, is available now (the title, ‘Without Him’, relates to the untimely death of her longtime editor, Xavier Barral). The project began when Paris’ Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature, or museum of hunting and nature, invited Calle to exhibit. It was shortly after her father’s death in 2015, and she was still mourning his loss. ‘I was in a fallow period, creatively, with no real desire to do anything,’ she says. ‘I considered quitting art altogether.’

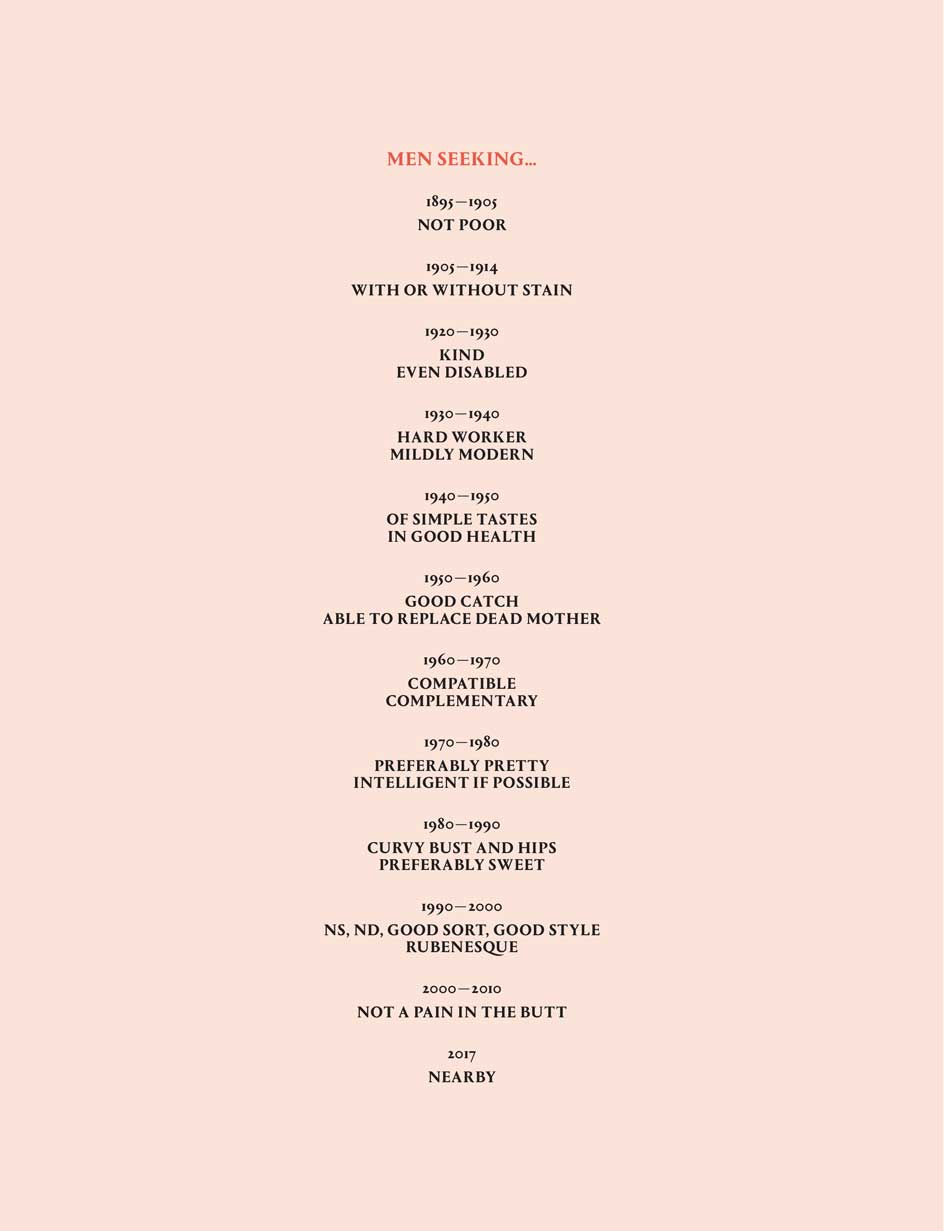

Gradually, the commission started to excite her, and she discovered that the hunting magazine Le Chasseur Français had been publishing matrimonial ads since 1895. Reasoning that the hunt for wild animals was not unlike the hunt for a potential mate, she combed through the archives to find what mating criteria best represented each decade. ‘They followed the trends of society. At first, money. Then virginity. After the war, many were related to physicality – a paralysed soldier could now accept a cleft lip.’ By 2017, when Calle included Tinder profiles in her research, she found that proximity was top of the list. To accompany the text, she is using her photos of watchtowers, (symbolising predators) and highway surveillance images of animals at night (symbolising prey).

Calle’s latest project explores the thrill, and the mundanity, of the matrimonial chase. Here, we see excerpts from lonely hearts advertisements Calle compiled from French hunting magazine Le Chasseur Français, Le Nouvel Observateur, online dating service Meetic as well as Tinder in latter years

Hunting of one sort or another is integral to much of Calle’s work. For an early project, Suite Vénitienne (1980), she followed a man from a party in Paris to Venice, stalking him through the Italian city and scrupulously noting her own emotional journey along the way. In other seminal works, she asked her mother to hire a private detective to trail her, worked as a hotel chambermaid and photographed the personal objects in guests’ rooms, and found a lost address book and called every name within to create a profile of its owner.

Though these works disclose much that is personal, their subjects remain as elusive as composite police sketches. ‘I don’t have the impression that I’m revealing intimacies,’ Calle explains. ‘These are moments that I highlight. To know that a man took this street and not another, or dined at 8pm, is not information. The investigation is more about me and my feelings than him. I’m the one going towards him.’ Imagining someone from a distance is a way of exposing herself.

But if Calle is an exhibitionist, she insists it is on her own terms. ‘It makes me laugh when people say, “You don’t know me, I know you well.” No. Not at all. Because I have chosen to tell certain stories and arrange them in my own way.’ Even when working as a stripper in her twenties, she attempted to control how men saw her: ‘I didn’t want men to approach me, so I looked at them with contempt. Maybe that’s what pleased them.’

Artworks by Calle, each pairing an image of a watchtower or animal with the text of lonely hearts ads from a specific decade, corresponding to overarching themes identified by the artist. Initially presented in French, the project has been translated into English for the first time within the November 2020 issue of Wallpaper*

The American curator Robert Storr regards Calle as one of the three or four most interesting French artists alive. He invited her to participate in a group show, ‘Dislocations’, at MoMA in 1991, and to represent France at the Venice Biennale in 2007. ‘I don’t consider her a capriciously self-centred woman,’ he says, but ‘someone who is obsessed by certain things. Those things are all connected to who she is, or feels she is, so she comes back to herself.’ He says there is a deep sadness palpable in her works, which he traces back to the early break-up of her family. Though her approach is conceptual, the themes she explores are relatable, and the feelings are genuine. ‘She is able to crystallise emotions that all of us have to some extent, and to give them her individual inflection in a way that makes them real.’ In fact, when Storr’s own parents died, he found himself longing for Calle’s photos of parental graves.

Calle’s parents separated when she was three years old, and she then lived with her mother in an apartment near Montparnasse Cemetery, crossing it on her way to school every day. Her father was an oncologist and art collector, mostly Pop Art but also photography. She carefully studied the photos on his walls, notably those of Duane Michals, who mixed images with text. ‘She was raised in a cultural, artistic environment,’ recalls the French artist Christian Boltanski, a longtime family friend, adding that Calle’s father was a first-rate collector who acquired many works early in artists’ careers.

At the University of Nanterre, Calle, then a left-wing radical, took a course from the renowned French sociologist Jean Baudrillard, who encouraged her to travel. When she dropped out of university to do so, he covered for her, adding her name to another student’s exam paper so she would get her diploma and her father would continue to support her. Calle travelled for seven years, to rural France, Greece, Mexico and beyond. In Bolinas, California, she took her first photographs, of tombstones inscribed simply with the words ‘Father’ and ‘Mother’.

RELATED STORY

Returning to Paris at age 26, she moved in with her father while honing her photography skills. (Long overlooked in favour of her ideas and text, her photographic talents were finally rewarded with the prestigious Hasselblad Award in 2010, followed by the Royal Photographic Society’s Centenary Medal in 2019.) Calle claims she became an artist as a way to ‘seduce’ him, in the non-sexual way the French employ the term. ‘I loved my father, and he was disappointed in me, because I was doing nothing with my life.’ At first, she photographed people walking the streets of Paris from behind. ‘I had forgotten my city, and didn’t know where to go, so I thought I would see where they went.’ She then invited people to sleep in her bed for eight hours at a time, while she photographed them. By chance, a woman she met at a market and invited into her bed was the wife of an art critic, who, upon learning of the project, invited Calle to take part in the 1980 Biennale des Jeunes, her first museum show.

When I ask if her father accepted all of this happening under his roof, she pauses: ‘I don’t even remember if I told him.’ Moments later, she stands up and starts searching for a pen, explaining that she is currently creating a work about everything she does not remember. She jots down the question of whether her father gave her permission for people to sleep in her bed. When I leave, she will write it up in the direct, concise style she has developed for museum walls.

Her phone rings, and the name Laurie Anderson appears on the screen. The two have been close friends since first meeting at the 1995 Telluride Film Festival, where Calle was showing her road movie No Sex Last Night. In the film, Calle and her boyfriend, filmmaker Greg Shephard, drive across America, each carrying a camera to document their dysfunctional relationship (it culminates with their short-lived marriage at a Las Vegas drive-thru window). Anderson was fascinated by the film and subsequently participated in two of Calle’s works, including Take Care of Yourself (2007), for which Calle asked 107 women, from a criminologist to a proofreader, to interpret a break-up letter she had received by email.

Calle hangs up and tells me that, in 2016, she, Anderson, and another friend decided to hold an impromptu – and non-legal – wedding ceremony at a church in San Francisco, just because it seemed like a beautiful place to get married. Somebody present took a photo, and the next day, to their surprise, it appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle as news. Calle says, ‘Laurie started receiving letters: “Why didn’t you tell me?” She wondered, “What do we do?” I said: “Nothing.”’

When I call Anderson a few weeks later, she chuckles at the memory, then says, ‘I took it seriously, I was happy to tie the knot with Sophie. I meant every word.’ I ask if the person we see in Calle’s artworks is the person she is. ‘Absolutely,’ Anderson responds. ‘And that’s a real achievement, because she doesn’t have a carefully constructed art persona. She really is that way, and talks that way, and thinks that way.’

Calle has many friends (her phone buzzes repeatedly while we talk), yet describes herself as a solitary person. She has been seeing her current companion, an architect, for 16 years, but does not spend more than eight days with him at a time. She has never wanted children. The closest she came to motherhood was the relationship with her cat, Souris; when he died in 2014 she asked various musicians (including Anderson, Bono and Pharrell Williams) to record songs about him, creating a triple album. I inquire if she has plans to replace him, and she stands up and calls out ‘Milou!’, explaining that a stray showed up on her doorstep three weeks earlier and has never left. ‘I wasn’t ready to do it over again. It was convenient to no longer have my cat, to be able to leave home without anything holding me back. I thought, “It will happen on its own, or not at all”. And it happened.’

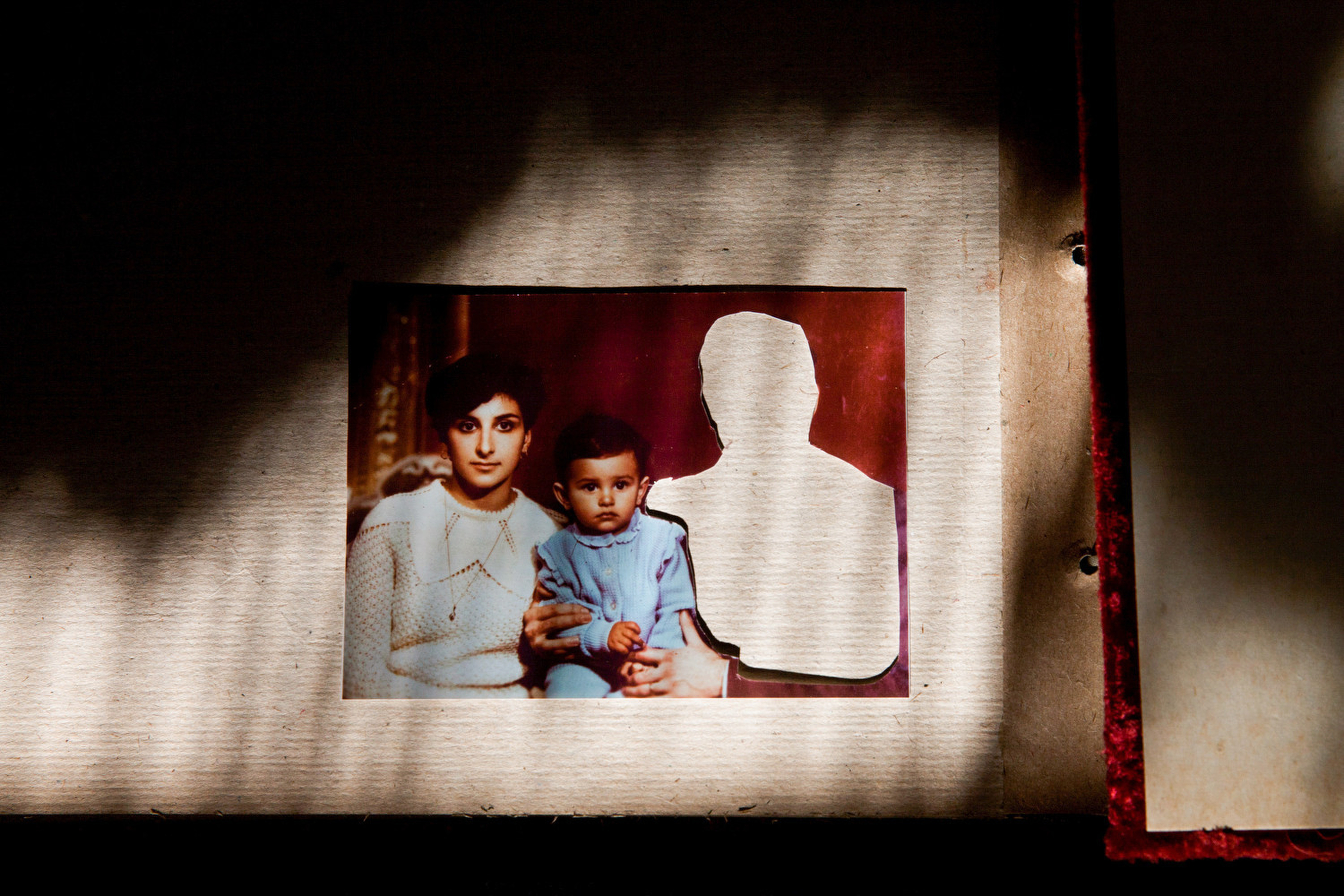

It is often written that Calle’s artwork revolves around intimacy, but she claims it is the idea of absence that drives her, ‘the things that are missing – my mother who is no longer here, a lover who leaves, an idea that doesn’t come’. Her mother, whom she describes as flamboyant and self-absorbed, once noted in her diary, ‘[Sophie] is so morbid that she will visit me in my grave more often than on rue Boulard’. When her mother was dying, in 2006, she was gratified to see Calle place a camera at the foot of her bed, to finally make an artwork about her (Rachel, Monique).

When Calle asked her father for permission to photograph him one last time, in 2015, he allowed her to shoot his hands. ‘He was more discreet,’ she says. ‘If I filmed him dying, it would be an act of war. Filming my mother dying was an act of love.’ These works have been a way for Calle to keep her parents around. But this is art, not therapy, and she emphasises that she does all of her work, no matter how personal, first and foremost ‘for the wall’.

One subject she has never explored is the fact that her mother and Jewish grandparents survived the Second World War because they were hidden in the mountains near Grenoble. ‘There were many in our family who died in the camps,’ she recalls. ‘My grandparents refused to talk about it. And I didn’t get interested early enough to insist. When it became necessary for me to know, they were all dead.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Currently, she is starting a piece around her own death. She has tried, unsuccessfully, to buy herself a burial plot at Montparnasse, where both her parents are buried. In the meantime, she has acquired a gravesite in Bolinas, California, where she took those first photos. It lies next to a site belonging to poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who was born in 1919. ‘I wanted to meet him, I explained we’d be neighbours in death, but he said no, he was too tired.’ In an embarrassment of riches, she was also offered a plot in Brooklyn, where she created a 25-year project in 2017, inviting visitors to write down their secrets and drop them into the earth through the slot of a marble obelisk she designed.

As she grows older, Calle’s obsessions remain the same, but her willingness to drop everything and pursue her subjects to the ends of the Earth has faded. In 2014, for an exhibition around the theme of highways, she spent a night in a toll booth, asking commuters, ‘Where could you take me?’ Afterwards, she realised, ‘Twenty years earlier, I would have closed my house, packed my toothbrush and my photo material, and told my friends I’d be back in 15 days. This time I went without a suitcase, because deep down inside I knew I’d go home.

This article originally appeared in the November 2020 issue of Wallpaper* (W*259) – on newsstands now and available for free download here

The artist at her Malakoff home. Photography: Alexandre Guirkinger

INFORMATION

Sans Lui, by Sophie Calle, published by Atelier EXB, €36

Amy Serafin, Wallpaper’s Paris editor, has 20 years of experience as a journalist and editor in print, online, television, and radio. She is editor in chief of Impact Journalism Day, and Solutions & Co, and former editor in chief of Where Paris. She has covered culture and the arts for The New York Times and National Public Radio, business and technology for Fortune and SmartPlanet, art, architecture and design for Wallpaper*, food and fashion for the Associated Press, and has also written about humanitarian issues for international organisations.

-

Click to buy: how will we buy watches in 2026?

Click to buy: how will we buy watches in 2026?Time was when a watch was bought only in a shop - the trying on was all part of the 'white glove' sales experience. But can the watch industry really put off the digital world any longer?

-

Don't miss these art exhibitions to see in January

Don't miss these art exhibitions to see in JanuaryStart the year with an inspiring dose of culture - here are the best things to see in January

-

Unmissable fashion exhibitions to add to your calendar in 2026

Unmissable fashion exhibitions to add to your calendar in 2026From a trip back to the 1990s at Tate Britain to retrospectives on Schiaparelli, Madame Grès and Vivienne Westwood, 2026 looks set to continue the renaissance of the fashion exhibition

-

Jean-Michel Othoniel takes over Avignon for his biggest ever exhibition

Jean-Michel Othoniel takes over Avignon for his biggest ever exhibitionOriginally approached by Avignon to mark their 25th anniversary as the European Capital of Culture, Jean-Michel Othoniel more than rose to the challenge, installing 270 artworks around the city

-

Joel Quayson’s winning work for Dior Beauty at Arles considers the theme ‘Face-to-Face’ – watch it here

Joel Quayson’s winning work for Dior Beauty at Arles considers the theme ‘Face-to-Face’ – watch it hereQuayson, who has won the 2025 Dior Photography and Visual Arts Award for Young Talents at Arles, imbues his winning work with a raw intimacy

-

What to see at Rencontres d’Arles 2025, questioning power structures in the state and family

What to see at Rencontres d’Arles 2025, questioning power structures in the state and familySuppressed memories resurface in sharply considered photography at Rencontres d'Arles 2025. Here are some standout photographers to see

-

‘With a small gesture of buying a postcard, we all become copyists’: the Louvre’s celebration of copying speaks to human nature

‘With a small gesture of buying a postcard, we all become copyists’: the Louvre’s celebration of copying speaks to human natureContemporary artists are invited to copy works from the Louvre in a celebration of the copyist’s art, a collaboration with Centre Pompidou-Metz

-

The glory years of the Cannes Film Festival are captured in a new photo book

The glory years of the Cannes Film Festival are captured in a new photo book‘Cannes’ by Derek Ridgers looks back on the photographer's time at the Cannes Film Festival between 1984 and 1996

-

Technology, art and sculptures of fog: LUMA Arles kicks off the 2025/26 season

Technology, art and sculptures of fog: LUMA Arles kicks off the 2025/26 seasonThree different exhibitions at LUMA Arles, in France, delve into history in a celebration of all mediums; Amy Serafin went to explore

-

Contemporary artist collective Poush takes over Château La Coste

Contemporary artist collective Poush takes over Château La CosteMembers of Poush have created 160 works, set in and around the grounds of Château La Coste – the art, architecture and wine estate in Provence

-

Architecture, sculpture and materials: female Lithuanian artists are celebrated in Nîmes

Architecture, sculpture and materials: female Lithuanian artists are celebrated in NîmesThe Carré d'Art in Nîmes, France, spotlights the work of Aleksandra Kasuba and Marija Olšauskaitė, as part of a nationwide celebration of Lithuanian culture