At home with artist Hank Willis Thomas

In our ongoing ‘At Home With' profile series, we go home, from home, with artists to hear about what they’re making, what’s making them tick, and the moments that made them. Here, we speak to American artist Hank Willis Thomas about how a premonition in January 2020 led him to the forefront of one of the most overdue cultural reckonings of the last 100 years

2020 was a very busy year for Hank Willis Thomas. For most artists, the peak of such a year might be the staging of a first major career retrospective, such as his presentation of ‘All Things Being Equal’ at the Cincinnati Art Museum this past autumn. But for Thomas, this was supplanted by his involvement in The 2020 Awakening, a new campaign launched by For Freedoms, the artist-led platform that he, photographer and political scientist Eric Gottesman and art producer/historian Michelle Woo launched in 2016.

Like many of For Freedoms’ other initiatives, The 2020 Awakening explores the way art and creativity can lift the lid on discussions around civic issues and shape the ideas, institutions and attitudes within American society. It believes in the power of creative collaboration to help reimagine the future.

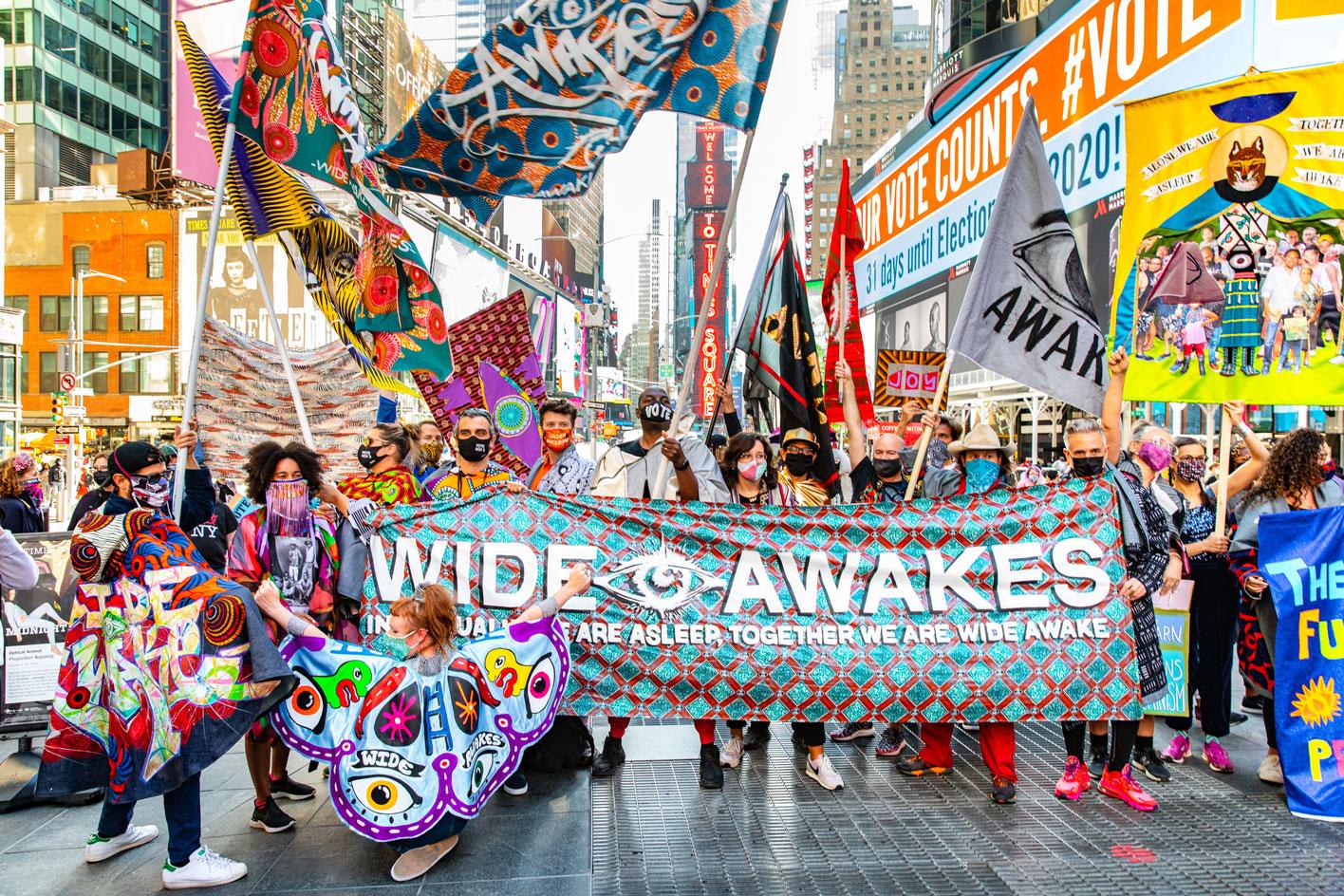

Inspired by the Wide Awakes of 1860, a youth organisation formed by abolitionists who campaigned for personal freedoms such as free speech and free men, The 2020 Awakening seeks to build an open-source network of Wide Awakes – creatives transcendent of region and origin – by providing resources through its Infinite Playbook that empowers anyone to use their voice in support of the new four freedoms: listening, healing, justice and awakening. Simply put, anyone can be a Wide Awake.

Above: Portrait of Hank Willis Thomas. Below: members of the Wide Awakes collective (left to right: Helen Banach, Wyatt Gallery, Rob Sinclair, Claudia Bestor, Alixa Garcia, Hank Willis Thomas and Coby Kennedy).

Thomas’ efforts for For Freedoms are the latest additions to the long and respected career that he has forged by creating photography, sculpture, video and public art that have continually confronted ideas of inequality, discrimination and bias.

Wallpaper*: Where are you as we speak?

Hank Willis Thomas: I’m at my studio. It’s actually in Gowanus now. I had to move [out of the Brooklyn Navy Yard] directly because of Covid. It was really complicated [to get in there] because they would only let one person in at a time. I’m now sharing with my friend [photographer] Justin Brice Guariglia and am just adjusting to being in a new place after being in the Navy Yard for five years.

Hank Willis Thomas, A Suspension of Hostilities, 2019. (Kayne Griffin Corcoran)

W*: Which career moment will you never forget?

HWT: I did the largest collaboration that I’ve ever done in my life last year; For Freedoms, Wide Awakes and the 2020 Awakening. It’s definitely much bigger than anything that I could have ever imagined. I became more than ever before, part of a community: all the Wide Awakes and all the people in For Freedoms, and all the people who chose to see themselves as part of something bigger and generously shared their creative energy – that was really life-altering for me.

W*: How does the synergy between different creative disciplines bring about a bigger impact?

HWT: I don’t know how to describe it other than when people come together and just show up with generosity and an open heart, you feel empowered just by the sheer audacity and willingness of others to be part of something. I don’t want this to feel cliché, but there are no words to describe what it’s like to feel very much in a community.

W*: For Freedoms and the idea for Wide Awakes both predate the events that went on to define 2020. How did the timing of everything that occurred give your cause greater meaning?

HWT: We were forced to re-evaluate everything we did and how we did them in direct response to [the pandemic]. For me, it was a pretty profound reckoning where not only were we trying to do something really important politically, but we were trying to do it in a context of a pandemic, where people were triggered, afraid and angry. We wanted to try and infuse hope and love and joy into one of the most charged and potentially toxic moments in American history.

Above and below: the Wide Awakes march in New York on 3 October 2020.

I had some weird foresight, a vision that there was going to be a need to tighten and expand our communities. I’m sure I wasn’t the only one to recognise that 2020 was going to be an important year. It was time for a wake-up call. We kind of frantically gathered people back in January. We held a Congress [in February 2020] where we talked about a creative plan of action and recognised that artists have an essential and critical role in imagining a future that we want to live in. If we can’t envision it, we can’t make it real.

The weekend after that, everything shut down because of the pandemic. And so we went from this high capacity, frantic mode of work work work, to being in a more mindful and patient and still place than I think anyone has ever been in this century. For the first time in maybe 150 years, more of us were in a similar state of awareness to other people around the world than ever before. So, we recognise the fragility of every life that our privilege cannot protect us from. We all have to consider how our actions and the actions of others have a ripple effect, and the need to be mindful and intentional with how we engage in the world and with others.

And then with the events of May 25th and the murder of George Floyd, it was the sparking of a great awakening of the 21st century, where no one could deny the injustice, no one could ignore the brutality. No one could even pretend that it was even unique, and when you started to see people come out of their homes, out of their fear places and into the streets, not only in rage but also enjoined and in community. With people who have never spoken out before coming together and speaking, it was really exciting and we realised it was part of a zeitgeist. The culmination of George and the polls and the election, and the energy that was put into being not reactionary, but visionary, was really kind of awesome.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

W*: As you said, these types of injustices aren’t anything new. What would you say made George Floyd's murder a turning point?

HWT: Well, it was really that there was no distraction. It was at a time when sporting events were closed, and no one could go to the movies. We actually had to deal with the world that we lived in. That is really what I think gave it the opportunity because we had become so accustomed to being distracted.

W*: Now that the election is over, how do you remain hopeful knowing that the country is still so divided?

HWT: We’re in a binary system [with only two choices] and the binary doesn’t give us enough options to embody the complexities of each of us. It’s very easy to divide. Even the idea that we are divided is a product of the stories we tell ourselves. It’s not really as simple as ‘those people over there.’ Those people are us. I think it’s also important to acknowledge what’s been happening in Hong Kong, in Paris, in Nigeria. For the first time, we have to recognise that we are part of the world. This isn’t just an issue that’s happening in the United States. People are collectively addressing police brutality and injustices that are being enabled by the government. So now that we realise that, there’s a greater responsibility to participate, to imagine and to dream.

W*: Where does the work go from here, in your view?

HWT: It goes. It doesn’t stop. We are the ones we’ve been waiting for, as [the South African poet] June Jordan said. They call it the movement because it doesn’t stop. We have to abandon the idea that we will ever get to a place where it’s enough and it’s all good. We can and must embrace that the movement for equality and justice for all is not over until our lives are over.

Hank Willis Thomas, Love Over Rules, 2017. Courtesy Hank Willis Thomas and Sites Unseen

W*: Which artists, writers and musicians have had the biggest impact on you?

HWT: For 2020, I’ll say: Alicia Keys, Swizz Beatz, Tariq Trotter aka Black Thought, because I work with them all. And then, Rashid Johnson, Sanford Biggers, José Parlá… I would just say For Freedoms in general. I mean, how many can I list? [laughs]

W*: What’s the most interesting thing you have read, watched or listened to recently?

HWT: One of the books I read last year was Finite and Infinite Games by James P. Carse. This idea of an infinite game being played just for the purpose of staying in a state of play, rather than a finite game, which is about winners and losers, has really been an epiphany for me as it’s relieved me of the need to feel like I’ve accomplished something. So that's why we want to really empower everyone who sees themselves as creative to be civic leaders, because without art, without creativity, our species literally will not survive.

I also recently watched Small Axe, [the film anthology series] by Steve McQueen. It, and especially the second episode, is incredible.

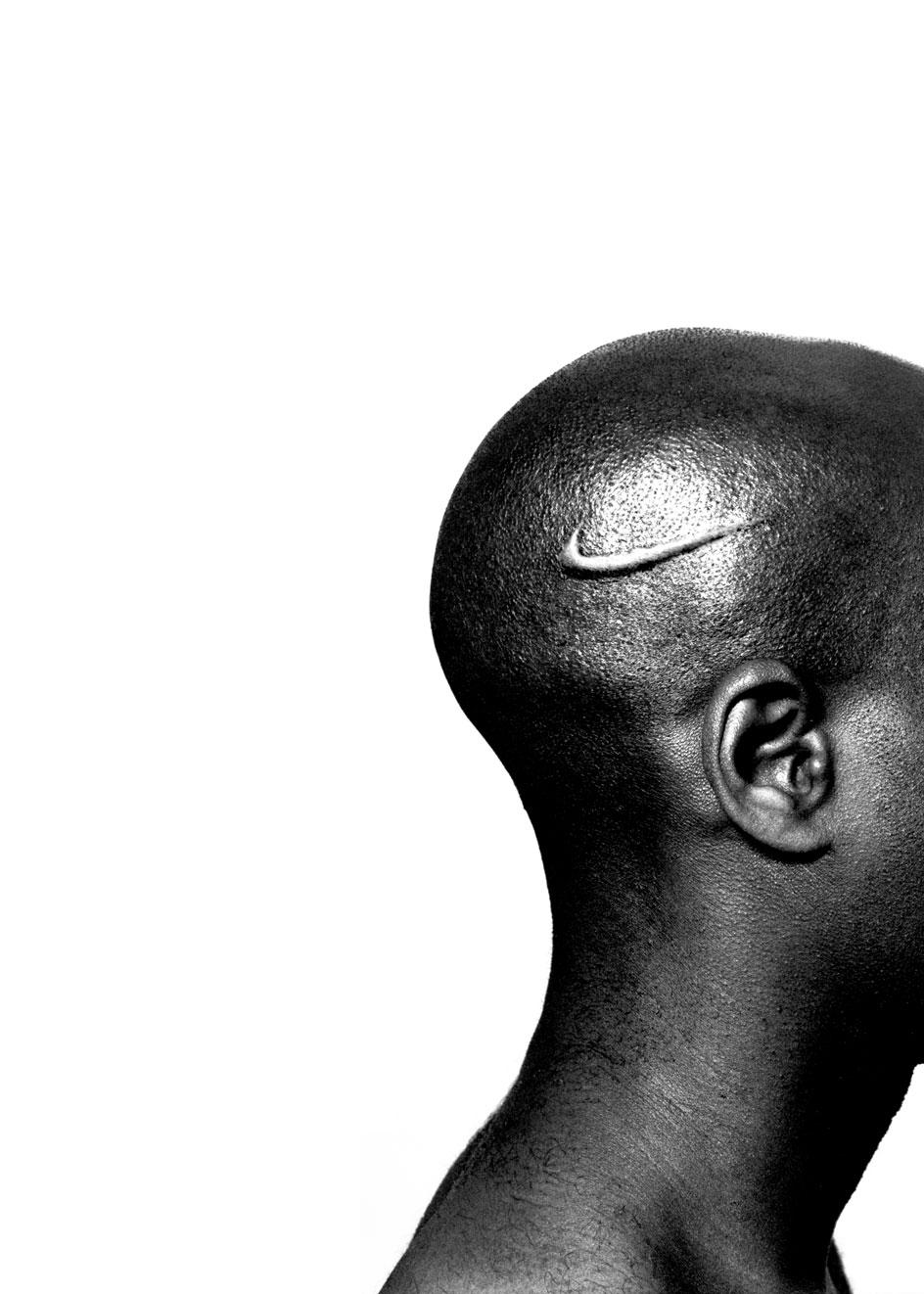

Hank Willis Thomas, Branded Head, 2003.

Hank Willis Thomas, Unity, 2019, an original work commissioned by the City of New York Department of Cultural Affairs Percent for Art Program, the Department of Transportation and the Department of Design and Construction.

INFORMATION

Pei-Ru Keh is a former US Editor at Wallpaper*. Born and raised in Singapore, she has been a New Yorker since 2013. Pei-Ru held various titles at Wallpaper* between 2007 and 2023. She reports on design, tech, art, architecture, fashion, beauty and lifestyle happenings in the United States, both in print and digitally. Pei-Ru took a key role in championing diversity and representation within Wallpaper's content pillars, actively seeking out stories that reflect a wide range of perspectives. She lives in Brooklyn with her husband and two children, and is currently learning how to drive.

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss

-

Ceramic artists: top trail-glazers breaking the mould

Ceramic artists: top trail-glazers breaking the mouldA way with clay: discover the contemporary ceramic artists firing up a new age for the medium

By Hannah Silver

-

The best art gifts for the creative in your life

The best art gifts for the creative in your lifeGet inspired with our ongoing guide to the best art gifts

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Cyprien Gaillard on chaos, reorder and excavating a Paris in flux

Cyprien Gaillard on chaos, reorder and excavating a Paris in fluxWe interviewed French artist Cyprien Gaillard ahead of his major two-part show, ‘Humpty \ Dumpty’ at Palais de Tokyo and Lafayette Anticipations (until 8 January 2023). Through abandoned clocks, love locks and asbestos, he dissects the human obsession with structural restoration

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

10 best art exhibitions to see in 2023, picked by Wallpaper* arts editor Harriet Lloyd-Smith

10 best art exhibitions to see in 2023, picked by Wallpaper* arts editor Harriet Lloyd-SmithTo usher in the new year, Wallpaper’s arts editor Harriet Lloyd-Smith highlights the best art exhibitions to see in 2023, and there’s a lot to look forward to

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Year in review: top 10 art interviews of 2022, chosen by Wallpaper* arts editor Harriet Lloyd-Smith

Year in review: top 10 art interviews of 2022, chosen by Wallpaper* arts editor Harriet Lloyd-SmithTop 10 art interviews of 2022, as selected by Wallpaper* arts editor Harriet Lloyd-Smith, summing up another dramatic year in the art world

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Veronica Ryan wins the 2022 Turner Prize

Veronica Ryan wins the 2022 Turner PrizeVeronica Ryan, the artist who honoured the Windrush generation, has been named winner of the 2022 Turner Prize in a ceremony held in Liverpool

By TF Chan

-

Yayoi Kusama on love, hope and the power of art

Yayoi Kusama on love, hope and the power of artThere’s still time to see Yayoi Kusama’s major retrospective at M+, Hong Kong (until 14 May). In our interview, the legendary Japanese artist vows to continue to ‘create art to leave the message of “love forever”’

By Megan C Hills

-

Textile artists: the pioneers of a new material world

Textile artists: the pioneers of a new material worldThese contemporary textile artists are weaving together the rich tapestry of fibre art in new ways

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith