At home with artist Julie Mehretu

Here, Camille Okhio discusses myths and motherhood with American artist Julie Mehretu ahead of her major retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art

Julie Mehretu speaks with the joy and conviction of someone who has had the freedom to investigate all their interests. Curiosity has led her to the myriad topics, objects and moments that inform her work, among them cartography, archaeology, the birth of civilisation and mycology. Since the 1990s, her practice has expanded outwardly in all directions like a spider web. A lack of understanding and preconceived notions among reviewers have often led to her work being flattened – simplified so that it is easily digestible – but in reality, her work is far from a simplistic investigation of any one topic. It encompasses multitudes.

The artist’s recent paintings are mostly large scale, but her early works on paper (often created with multiple layers – one sheet of Mylar on top of another) are as small as a six-inch square. The works often comprise innumerable minuscule markings – tremendous force and knowledge communicated through delicate inkings and streaks. Their layers reveal, rather than obfuscate. And though Mehretu’s creative process springs from a desire to understand herself better, the work itself is in no way autobiographical.

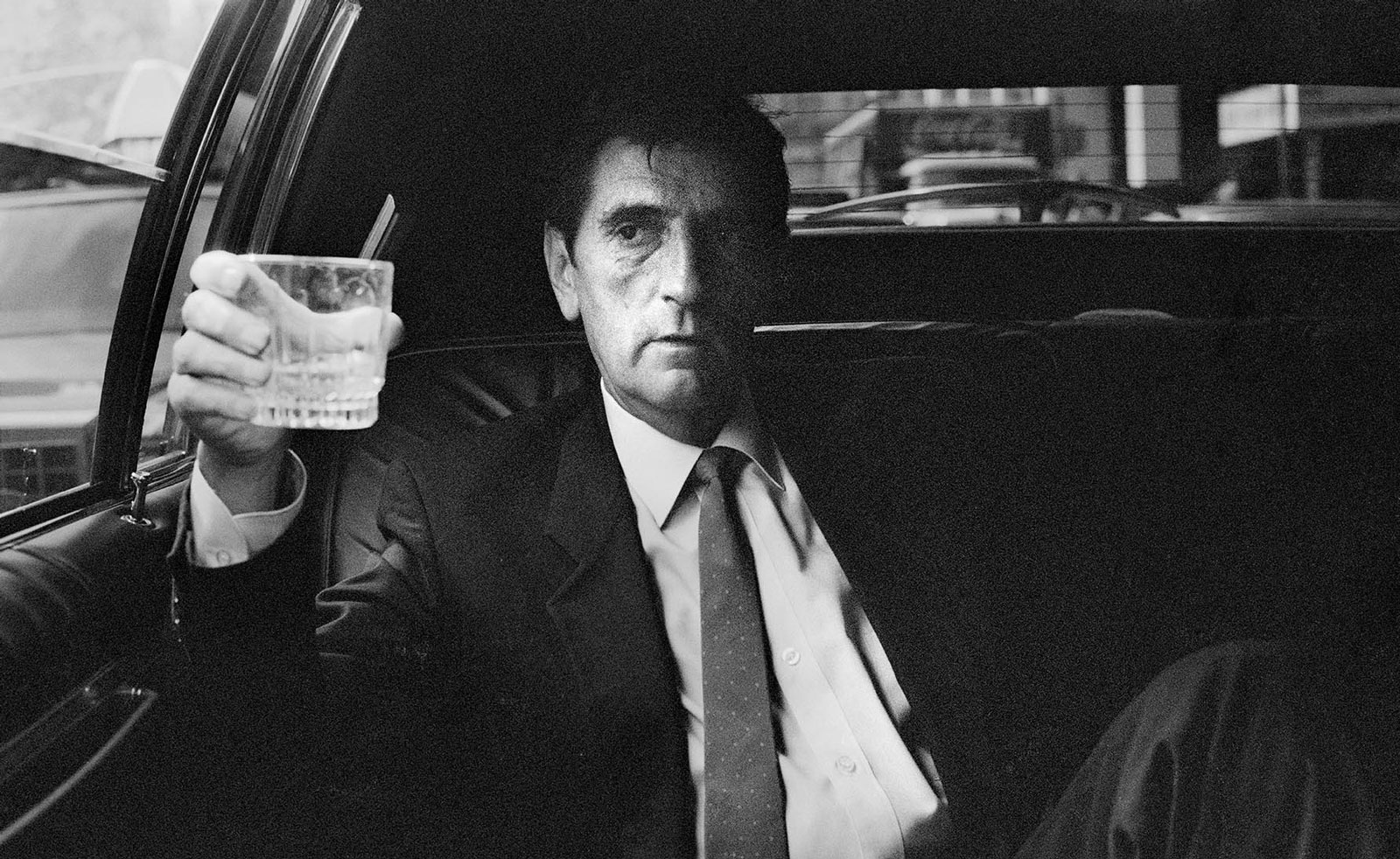

Portrait of Julie Mehretu

Born in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, on the tails of a continental rejection of colonialism, and raised there, then in Michigan, Mehretu has a flexible and full-hearted understanding of home. It is not one physical place, but many, all holding equal importance. On 25 March, Mehretu will present her first major retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art, with works spanning 1996 to 2019. The institution is an important one for Mehretu, as it played host to several pivotal shows in her youth.

Her exhibition has served as an impetus for Mehretu to look back at her already prolific career, observing and organising the thoughts, questions and answers she has put forth for over two decades. The six years it took to bring this exhibition together proved an incredibly valuable time of reflection, fatefully dovetailing with a year of quarantine.

Wallpaper*: Where are you as we speak?

Julie Mehretu: I’m in my studio on 26th Street, right on the West Side Highway. I’ve worked here for 11 years.

W*: Are there any artists, writers or thinkers that have had a meaningful impact on you?

JM: I don’t know how to answer that because there are literally so many! It’s constantly changing. Right now, Kara Walker, David Hammons, William Pope.L, and younger artists like Jason Moran (who has made amazing work around abstraction). There are so many artists that have been informative and important to me: Frank Bowling, Jack Whitten, Caravaggio.

I also look at a lot of prehistoric work, from as far back as 60,000 years ago, as well as cave paintings from 6th century China and early prehistoric drawings in the caves of Australia.

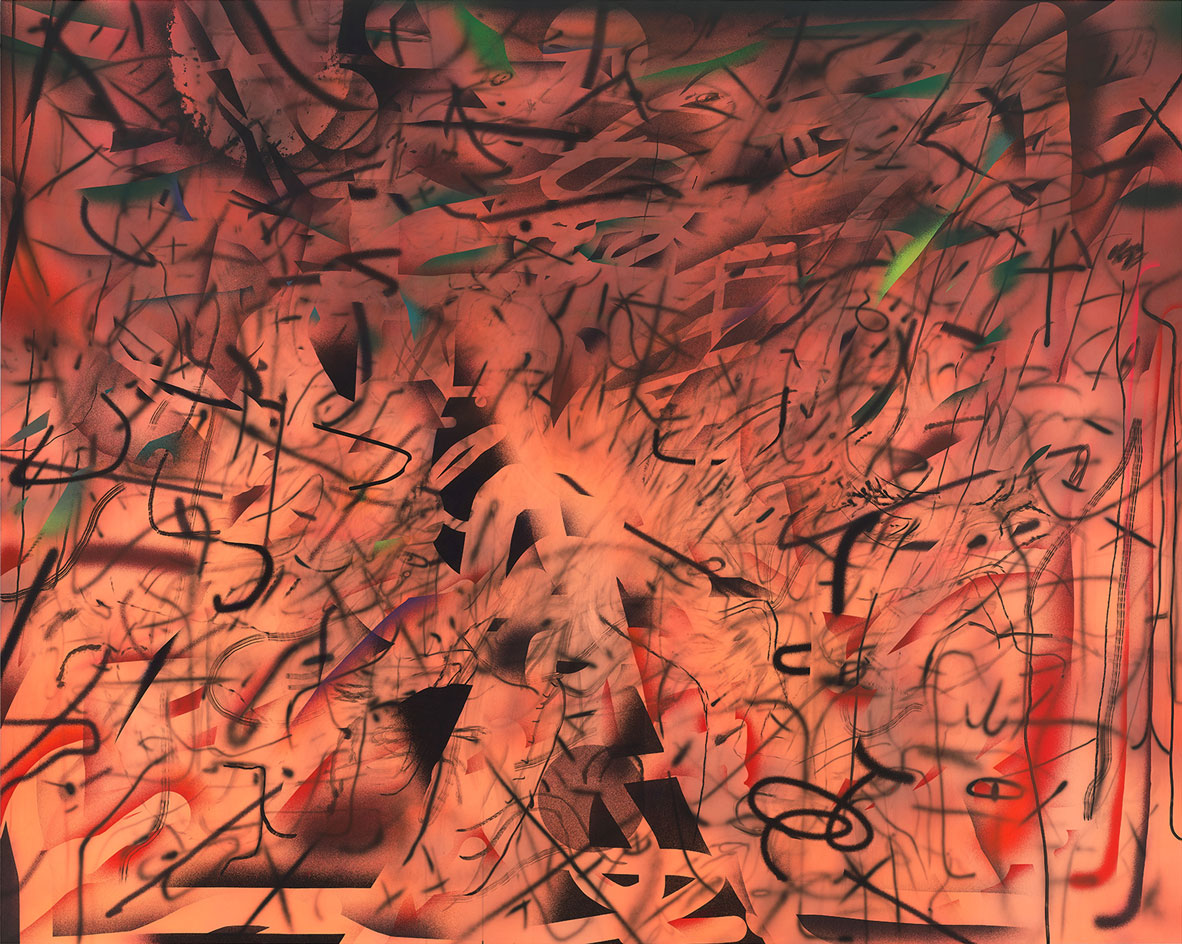

Julie Mehretu, Hineni (E. 3:4), 2018. Centre Pompidou, Paris, Musée national d’art moderne/Centre de création industrielle; gift of George Economou, 2019.

W*: What’s the most interesting thing you have read, watched or listened to recently?

JM: For the last few weeks I’ve been immersed in Steve McQueen films. I've been bingeing on lovers rock music. And a TV show that really moved me was [Michaela Cole’s] I May Destroy You. It’s difficult, but it was really well done and powerful.

Ocean Vuong’s novel On Earth We Are Briefly Gorgeous is amazing. The Mushroom at the End of the World by Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing is a really incredible book too – she studies this mushroom that became a delicacy in Japan in the 7th century. It started growing in deforested areas – it's in these places destroyed by human beings that these mushrooms survive. [I find it interesting] that this mushroom grows on the edge of precarity and destruction. Like with Black folks, there is a constant aspect of insisting on yourself and reinventing yourself in the midst of constant effort of destruction.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

W*: What was the first piece of art you remember seeing? How did you feel about it?

JM: One of the first times I remember being moved by a work of art was looking through my mother’s Rembrandt book. We brought so few things back from Ethiopia and that was one of them. [Particularly] Rembrandt’s The Sacrifice of Isaac. That story is so intense. I was so moved by the light and the skin and the way the paint made light and skin.

W*: Do you travel? If so, what does travel afford you, and what have you missed about it during Covid-19?

JM: I travel a lot, but I haven't travelled this year. There has been this amazing sense of suspension and a pause in that. I miss travelling, but going to look at art, watching films, reading novels and listening to music is the way I travel now. For instance, I’ve been listening to Afro-Peruvian music and now I want to go to Peru.

Before I know it we will be back in this fast-paced, zooming-around environment – there is something I want to savour by staying here, now, in this time and absorbing as much as I can.

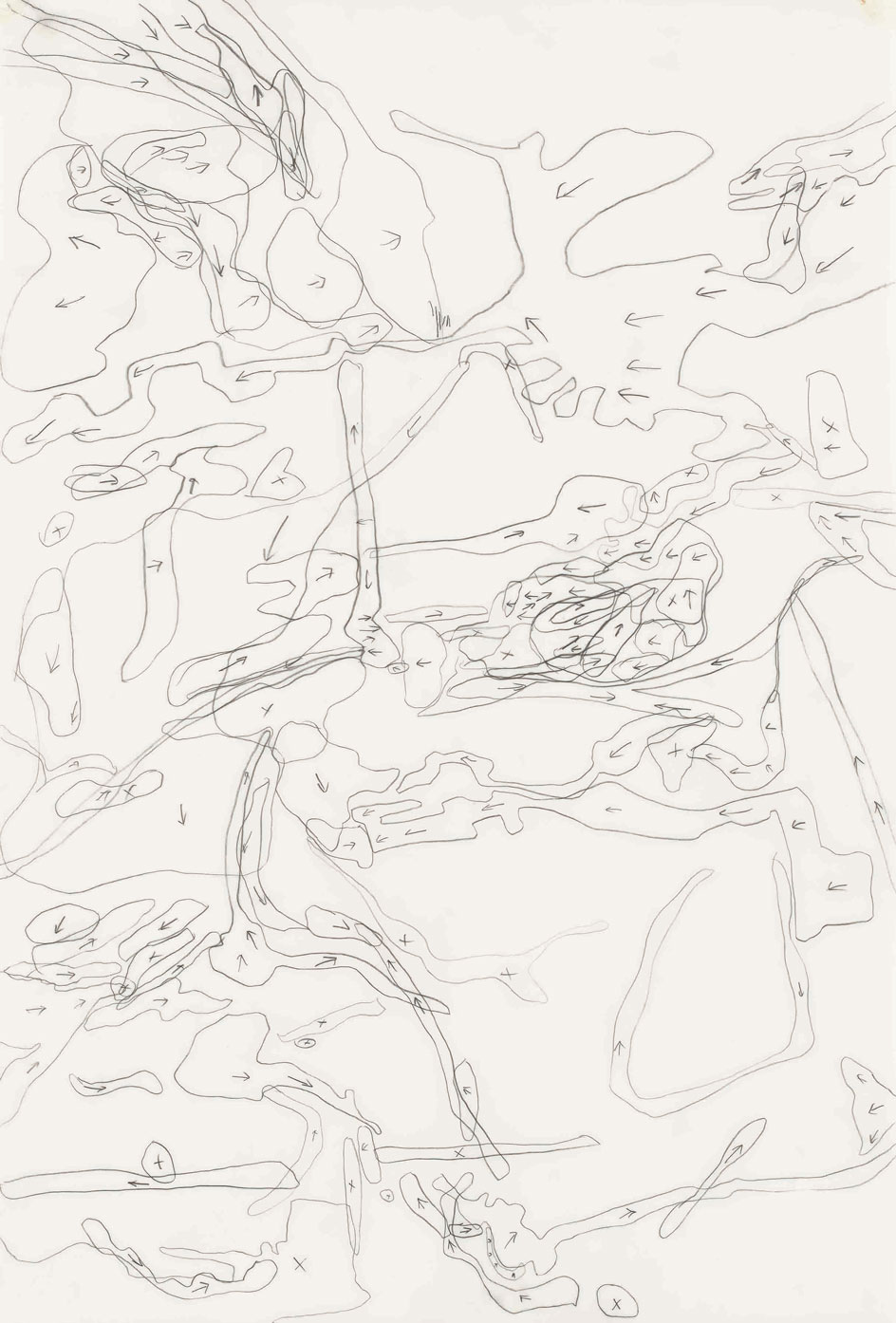

Julie Mehretu, Mind-Wind Field Drawings (quarantine studio, d.h.) #1, 2019-2020. Private collection,

W*: You are said to have a vast collection of objects and images. Walk me through your collection – what areas, materials, makers and things have the largest presence and why?

JM: When you enter our home there is this long hallway. Framed along the wall we have around 20 fluorescent Daniel Joseph Martinez block-printed posters he made with words – almost poems. Our kids grew up reading those. One says ‘Sometimes I can’t breathe’ and another one says ‘Don’t work’, while some are really long.

We also have a great Paul Pfeiffer photograph of one from the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse series. We have a group of Richard Tuttle etchings right over our dining table. We have an amazing David Hammons body print as well, and my kids’ work is all over the house.

W*: As the daughter of immigrants and an immigrant yourself – how do you conceptualise home and how do you create it?

JM: There were a lot of times I felt very transient – as a student and a young adult, going in and out of school and residency programmes. It always came back to music and food. There are certain flavours, foods, music, smells that you take wherever you go. Also as a mother, I’m building a home for my children. Home becomes something else because of them. They are the core of home now.

W* How has motherhood affected your practice?

JM: I became much more productive when I had kids for several reasons – one is that I felt a lot of pressure to make [work] in the time I wasn't with them, which of course is unsustainable. A large part of making is not making – thinking and searching.

When I got to work I could get into it much more quickly. Kids grow and change so fast, you feel time is passing so you need to use it. I wasn't going to stop working, that's for sure. All women who are pushing in their lives make that choice.

Julie Mehretu, Mogamma (A Painting in Four Parts) Part 1, 2012. Guggenheim Abu Dhabi.

W*: What is your favourite myth and why does it hold importance for you?

JM: Right now I'm reading Greek myths to my ten-year-old. We’ve read them before, but he wanted to read them again. I still read to him at night even though he's a voracious reader himself.

The myths I remember the most are myths I’ve come across in visual works. Titian’s Diana and Actaeon – I know that myth so well because of his painting. Bernini’s mesmerising sculpture of Apollo and Daphne I saw in Rome, where her body becomes a tree. The leaves are so delicately carved into the marble, it's a work of incredible beauty. I’ve been considering this deconstructionist approach to mythology. Storytelling becomes this place to interrogate propositions, which is what I think mythology does.

W*: Have you experienced a flattening of your work?

JM: I'm always concerned with flattening and pigeonholing. That is something that happens to artists like us all the time. When I first was working and showing there was a bit of that happening with my work. It was put into the space of cartography or an architectural analysis of it. It was said to be autobiographical work.

The art world tries to consume. There is this desire to flatten and the desire for Black artists to be a reflection of their experience. I don't think any artist is like that at all. In reality, none of us are flat. We all contain multitudes and are complicated – that has always been the core of the Black radical tradition.

In our ongoing profile series we talk to artists about what they’re making, what’s making them tick, and the moments that made them.

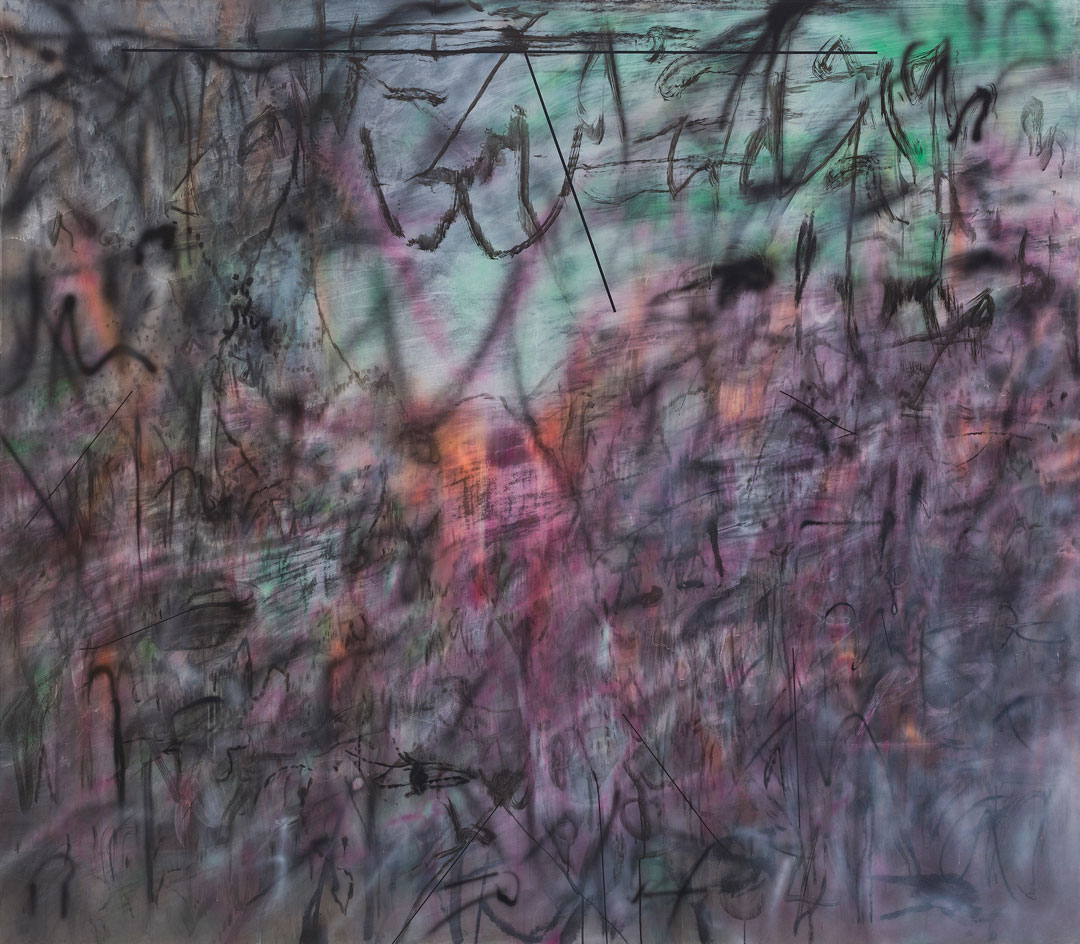

Julie Mehretu, Conjured Parts (eye), Ferguson, 2016. The Broad Art Foundation, Los Angeles.

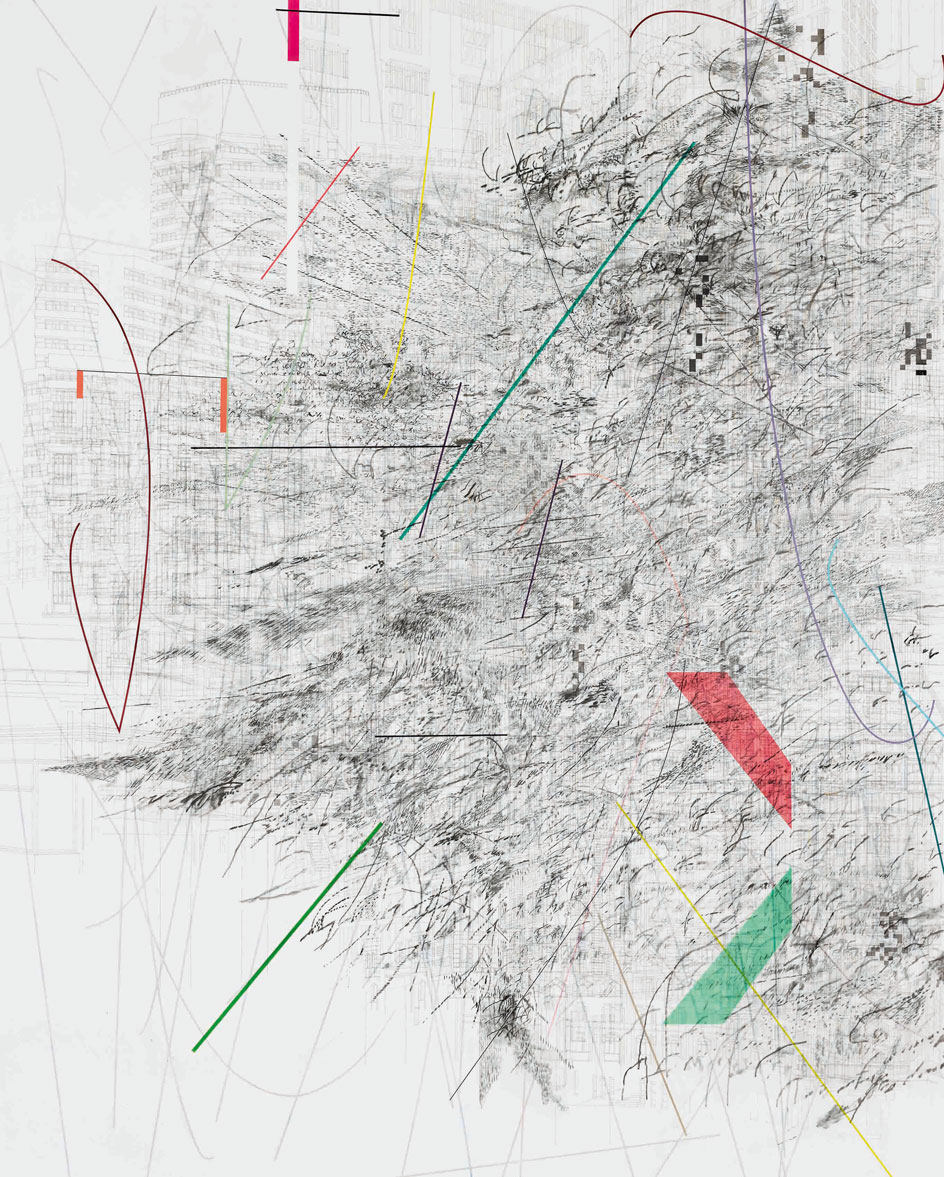

Julie Mehretu, Migration Direction Map (large), 1996. Private collection.

INFORMATION

Julie Mehretu’s retrospective runs from 25 March - 8 August, 2021 at the Whitney Museum of American Art. whitney.org

ADDRESS

99 Gansevoort St

New York, NY 10014

-

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressing

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressingPart of our monthly Uprising series, Wallpaper* meets Benjamin Barron and Bror August Vestbø of All-In, the LVMH Prize-nominated label which bases its collections on a riotous cast of characters – real and imagined

By Orla Brennan

-

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationship

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationshipAnnouncing their marriage during Milan Design Week, the brands unveiled a collection, a car and a long term commitment

By Hugo Macdonald

-

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craft

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craftThe heritage furniture manufacturer is training a new generation of leather artisans

By Cristina Kiran Piotti

-

‘Humour is foundational’: artist Ella Kruglyanskaya on painting as a ‘highly questionable’ pursuit

‘Humour is foundational’: artist Ella Kruglyanskaya on painting as a ‘highly questionable’ pursuitElla Kruglyanskaya’s exhibition, ‘Shadows’ at Thomas Dane Gallery, is the first in a series of three this year, with openings in Basel and New York to follow

By Hannah Silver

-

Leonard Baby's paintings reflect on his fundamentalist upbringing, a decade after he left the church

Leonard Baby's paintings reflect on his fundamentalist upbringing, a decade after he left the churchThe American artist considers depression and the suppressed queerness of his childhood in a series of intensely personal paintings, on show at Half Gallery, New York

By Orla Brennan

-

Desert X 2025 review: a new American dream grows in the Coachella Valley

Desert X 2025 review: a new American dream grows in the Coachella ValleyWill Jennings reports from the epic California art festival. Here are the highlights

By Will Jennings

-

This rainbow-coloured flower show was inspired by Luis Barragán's architecture

This rainbow-coloured flower show was inspired by Luis Barragán's architectureModernism shows off its flowery side at the New York Botanical Garden's annual orchid show.

By Tianna Williams

-

‘Psychedelic art palace’ Meow Wolf is coming to New York

‘Psychedelic art palace’ Meow Wolf is coming to New YorkThe ultimate immersive exhibition, which combines art and theatre in its surreal shows, is opening a seventh outpost in The Seaport neighbourhood

By Anna Solomon

-

Wim Wenders’ photographs of moody Americana capture the themes in the director’s iconic films

Wim Wenders’ photographs of moody Americana capture the themes in the director’s iconic films'Driving without a destination is my greatest passion,' says Wenders. whose new exhibition has opened in New York’s Howard Greenberg Gallery

By Osman Can Yerebakan

-

20 years on, ‘The Gates’ makes a digital return to Central Park

20 years on, ‘The Gates’ makes a digital return to Central ParkThe 2005 installation ‘The Gates’ by Christo and Jeanne-Claude marks its 20th anniversary with a digital comeback, relived through the lens of your phone

By Tianna Williams

-

In ‘The Last Showgirl’, nostalgia is a drug like any other

In ‘The Last Showgirl’, nostalgia is a drug like any otherGia Coppola takes us to Las Vegas after the party has ended in new film starring Pamela Anderson, The Last Showgirl

By Billie Walker