At home with artist Sarah Oppenheimer

In our interview profile series, we hear about what artists are making, what’s making them tick, and the moments that made them. Sarah Oppenheimer, master of architectural manipulations, talks spatial hierarchies, human touch and the creation of her ‘Sensitive Machine’, now on view in New York

Sarah Oppenheimer’s work explores how individual and collective action can shape the spaces we inhabit. A master of architectural manipulations, her work is interactive, psychological, performative, and at its heart, deeply social.

Her practice subverts perceptions and turns spatial hierarchies inside out. vertiginous, dizzying and majestic, it leaves viewers questioning the stability and veracity of their surroundings. Oppenheimer has just unveiled ‘Sensitive Machine’ at the Wellin Museum of Art, New York. Her most challenging installation to date, it introduces four newly created ‘instruments’ linked to existing lighting tracks and subdividing walls. Working collaboratively, viewers can touch and turn the structures, altering lines of sight, entirely reconfiguring the gallery space.

In recent times, when tactile experiences have been scarce, ‘Sensitive Machine’ offers a new dimension to bodily engagement and communication, where viewers develop an acute awareness of their shifting environment and those around them.

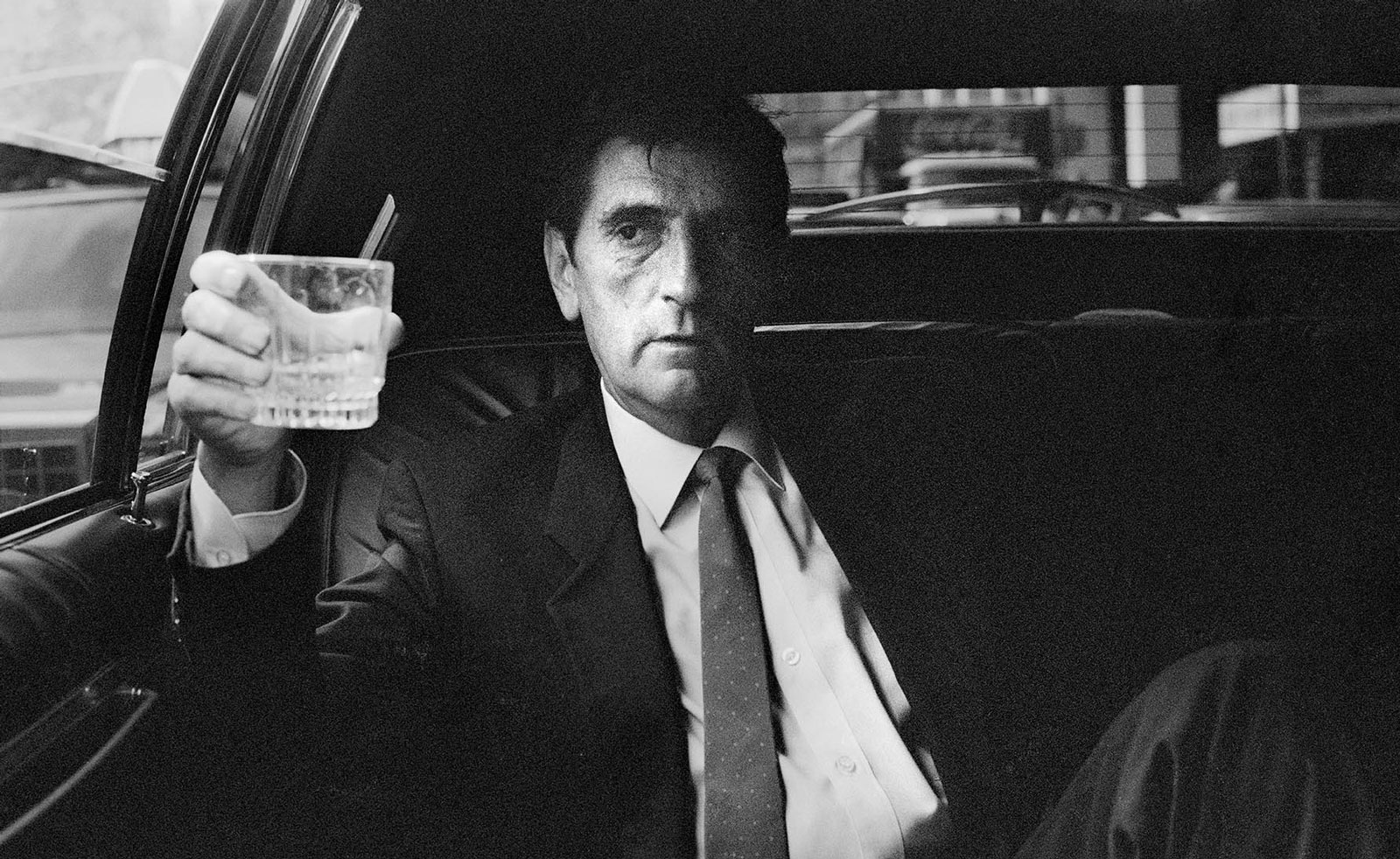

Portrait of artist Sarah Oppenheimer.

Wallpaper*: Where are you as we speak?

Sarah Oppenheimer: I am sitting in a room. An open sash window backlights the computer screen. Overhead lights are off. A door behind me is ajar. The room around me modulates my voice, my gesture, and my visual field.

My opening sentence shares the title of the 1969 sound work by Alvin Lucier. In that work, Lucier repeats the statement ‘I am sitting in a room’ while recording his voice. With each reiteration, the recording layers the ambient sound of the room, obscuring the original iteration and blurring the boundary between echo and architecture.

Sarah Oppenheimer: 'Sensitive Machine' at the Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, on view until December 5, 2021.

W*: You’ve just opened ‘Sensitive Machine’ at the Wellin Museum of Art. Can you talk us through the ideas behind the show?

SO: ‘Sensitive Machine’ is a hybrid: part human, part digital, part analogue. Touch sets in motion a dynamic exhibition system. Four instruments are interconnected: turning the input of one instrument alters the configuration of another. As visitors manually activate each instrument, a choreography of spatial change is set in motion. Lighting tracks slip between the vertical surfaces of sliding walls. Luminosity levels fluctuate while sightlines are interrupted and revealed.

‘Sensitive Machine’ understands the built environment as a mechanism whose technical dimensions are profoundly social. Museum visitors become aware of one another’s presence, their bodily engagement, and the extent of their own reach. The residue of touch lingers and communicates; we sense others shaping the space we inhabit.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

W*: Visitors can manually activate the work, and in turn, reconfigure the space. Why was tactility important?

SO: Now more than ever, we must consider how spatial proximity and spatial agency are defined. What are the implications of expanding our institutional footprint across non-contiguous spaces? What are the consequences of augmenting human gestures with digitally enhanced motorised action?

‘Sensitive Machine’ amplifies our tactile traces while inviting us to learn the extent of our own reach. Set in motion by the human hand, the temporal frequency of each of the exhibition’s four instruments is scaled to the body. Undulating lights and sliding walls remain in phase with human gesture. Each oscillation creates a temporal counterpoint, shaping passage and stretching the tempo of human touch.

Sarah Oppenheimer: 'Sensitive Machine' at the Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, on view until December 5, 2021.

W*: The show was nine years in the making. How does the initial concept compare to the outcome?

SO: I have been in dialogue with the Wellin's director, Tracy Adler, for years about the possibility of working together. While on a site visit to the Wellin in 2017, I encountered an extraordinary mechanism embedded within the roller of an old printing press. The analogue technology of that older mechanism translated rotary motion into linear oscillation. In contrast to projects I was developing at the time (Pérez Art Museum Miami, 2016; Wexner Center for the Arts, 2017; and Mass MoCA, 2019) – in which touch rotated a single glass volume – the printing press mechanism enabled linkage and temporal coordination between spatially disparate elements.

Working in collaboration with the Yale University Engineering department, my studio began incorporating rotary-linear motion into architectural instruments. We developed detailed digital models of the mechanical elements and constructed physical models to explore how human gesture could set linked objects in motion.

Prototyping began on a small scale, allowing us to consider how touch shapes the position of handheld objects. As we gained fluency with the technical limitations and possibilities of this phased mechanism, the system expanded in scale to include architectural elements such as glass planes, steel tubes, and wood panels. With each step of the process, we continued to evaluate and modulate the gestural qualities required to activate the kinetic relay.

Sarah Oppenheimer: ’Sensitive Machine’ at the Wellin Museum of Art at Hamilton College, on view until December 5, 2021.

W*: Your workshop at Yale School of Art is also titled ‘Sensitive Machine’. How does your educational work feed into your art practice and vice versa?

SO: In 2016 I began to explore these questions in a series of workshops. Participants were asked to collaborate on the design and construction of a prosthesis that allowed one body to shape the gesture of another. As users explored the sensorial feedback between prosthesis and body, they learned how the device informed the gestural actions of each participant.

Sensors were affixed to the prosthesis at Yale University’s large-scale motion capture studio. Movement was captured by an array of overhead cameras and displayed as a dynamic point cloud image in real time. We wondered: Would the participants use the projection as proprioceptive feedback? Would this feedback alter the collaborative manipulation of a prosthetic machine?

W*: What’s the most challenging art project you’ve ever worked on?

SO: The instruments arrayed in N-01 and Sensitive Machine are the most challenging (and exciting) works to date. Their evolution has required the studio to develop new methods of spatial design. Prior design tools such as architectural plans and scale models have given way to network typologies and kinematic prototypes.

Inserting linkages between instruments had tactile and temporal repercussions. The greater the number of linkages, the greater the friction in the overall system. Each sequential prototype aimed at reducing friction in the kinetic chain so that the viewers’ touch could remain light and informal while displacing apparently stable elements of the surrounding architecture. As more instruments were linked, their motion became nested and phased. This introduced the challenge of phasing the timing of each artwork.

Sarah Oppenheimer, N-01, 2020. Aluminum, steel, glass and existing architecture. Installation view: Kunstmuseum, Thun. Switzerland

Sarah Oppenheimer, P-021110, 2014, Aluminum, glass and existing architecture. Location: Von Bartha, Basel Switzerland.

W*: Which artists, writers, thinkers or musicians have had the biggest impact on you?

SO: My work shuffles the spatial hierarchies of observation and influence. Reciprocal engagement requires a multiplicity of vantage points, eschewing a dominant position and centralised location while emphasising agency, sensitivity, and exchange. In developing these arrangements, I look to and learn from network theory, cybernetics, behavioural psychology, and the technical histories underpinning contemporary architecture.

The study of technical devices has had a tremendous impact on my work, especially those devices that measure, standardise, and regulate our environment. Apparatuses such as rulers, scales, clocks, metronomes, barometers, and tuning forks mediate the experience of the built environment. They enable social collaboration and human coordination in a living public space.

Art historical precedent weaves in and around these questions. I have been influenced by the work of Lygia Clark, Stephen Willats, Maria Nordman, Eileen Gray, and many others. In the case of each of these extraordinary precedents, the work is the medium of social exchange

Sarah Oppenheimer, S-281913, 2016. Aluminum, glass and architecture. Installation view: Perez Art Museum Miami. USA.

Sarah Oppenheimer, P-021110, 2014. Aluminum, glass and existing architecture. Location: Von Bartha, Basel Switzerland.

Sarah Oppenheimer, 610-3365, 2008, Plywood and existing architecture. Location: Mattress Factory, PA.

Sarah Oppenheimer, S-337473, 2017 Steel, glass and architecture. Installation view: Wexner Center for the Arts. USA.

INFORMATION

‘Sarah Oppenheimer: Sensitive Machine’, until 5 December 2021, Wellin Museum of Art, Hamilton College, hamilton.edu

198 College Hill Rd

Clinton, NY 13323

Harriet Lloyd-Smith was the Arts Editor of Wallpaper*, responsible for the art pages across digital and print, including profiles, exhibition reviews, and contemporary art collaborations. She started at Wallpaper* in 2017 and has written for leading contemporary art publications, auction houses and arts charities, and lectured on review writing and art journalism. When she’s not writing about art, she’s making her own.

-

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressing

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressingPart of our monthly Uprising series, Wallpaper* meets Benjamin Barron and Bror August Vestbø of All-In, the LVMH Prize-nominated label which bases its collections on a riotous cast of characters – real and imagined

By Orla Brennan

-

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationship

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationshipAnnouncing their marriage during Milan Design Week, the brands unveiled a collection, a car and a long term commitment

By Hugo Macdonald

-

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craft

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craftThe heritage furniture manufacturer is training a new generation of leather artisans

By Cristina Kiran Piotti

-

Leonard Baby's paintings reflect on his fundamentalist upbringing, a decade after he left the church

Leonard Baby's paintings reflect on his fundamentalist upbringing, a decade after he left the churchThe American artist considers depression and the suppressed queerness of his childhood in a series of intensely personal paintings, on show at Half Gallery, New York

By Orla Brennan

-

Desert X 2025 review: a new American dream grows in the Coachella Valley

Desert X 2025 review: a new American dream grows in the Coachella ValleyWill Jennings reports from the epic California art festival. Here are the highlights

By Will Jennings

-

This rainbow-coloured flower show was inspired by Luis Barragán's architecture

This rainbow-coloured flower show was inspired by Luis Barragán's architectureModernism shows off its flowery side at the New York Botanical Garden's annual orchid show.

By Tianna Williams

-

‘Psychedelic art palace’ Meow Wolf is coming to New York

‘Psychedelic art palace’ Meow Wolf is coming to New YorkThe ultimate immersive exhibition, which combines art and theatre in its surreal shows, is opening a seventh outpost in The Seaport neighbourhood

By Anna Solomon

-

Wim Wenders’ photographs of moody Americana capture the themes in the director’s iconic films

Wim Wenders’ photographs of moody Americana capture the themes in the director’s iconic films'Driving without a destination is my greatest passion,' says Wenders. whose new exhibition has opened in New York’s Howard Greenberg Gallery

By Osman Can Yerebakan

-

20 years on, ‘The Gates’ makes a digital return to Central Park

20 years on, ‘The Gates’ makes a digital return to Central ParkThe 2005 installation ‘The Gates’ by Christo and Jeanne-Claude marks its 20th anniversary with a digital comeback, relived through the lens of your phone

By Tianna Williams

-

In ‘The Last Showgirl’, nostalgia is a drug like any other

In ‘The Last Showgirl’, nostalgia is a drug like any otherGia Coppola takes us to Las Vegas after the party has ended in new film starring Pamela Anderson, The Last Showgirl

By Billie Walker

-

‘American Photography’: centuries-spanning show reveals timely truths

‘American Photography’: centuries-spanning show reveals timely truthsAt the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, Europe’s first major survey of American photography reveals the contradictions and complexities that have long defined this world superpower

By Daisy Woodward