At home with Jeff Koons

We visit Jeff Koons (via Zoom) in his New York City studio to discuss transcendence, the Renaissance, and his show, ‘Shine’ at Palazzo Strozzi, Florence

Recent times have demanded reflection, and no artist has used this motif in more variety, or notoriety, than American artist Jeff Koons.

Throughout his career, Koons has hoovered up art history – executed in literal terms with his 1980s vacuum cleaner readymades – and refashioned the fragments into something entirely new. Through kitsch-rich household ornaments and cut-and-pasted motifs from pop culture, he elevates the low-brow onto the pedestal of high art, until we barely know the difference.

Koons has a knack for reflecting the idealism in human history; reflecting contemporary times, in all its mass-consumerist, superficial and voyeuristic banality; and making work that literally reflects, consumes and warps its surroundings, and all those who observe.

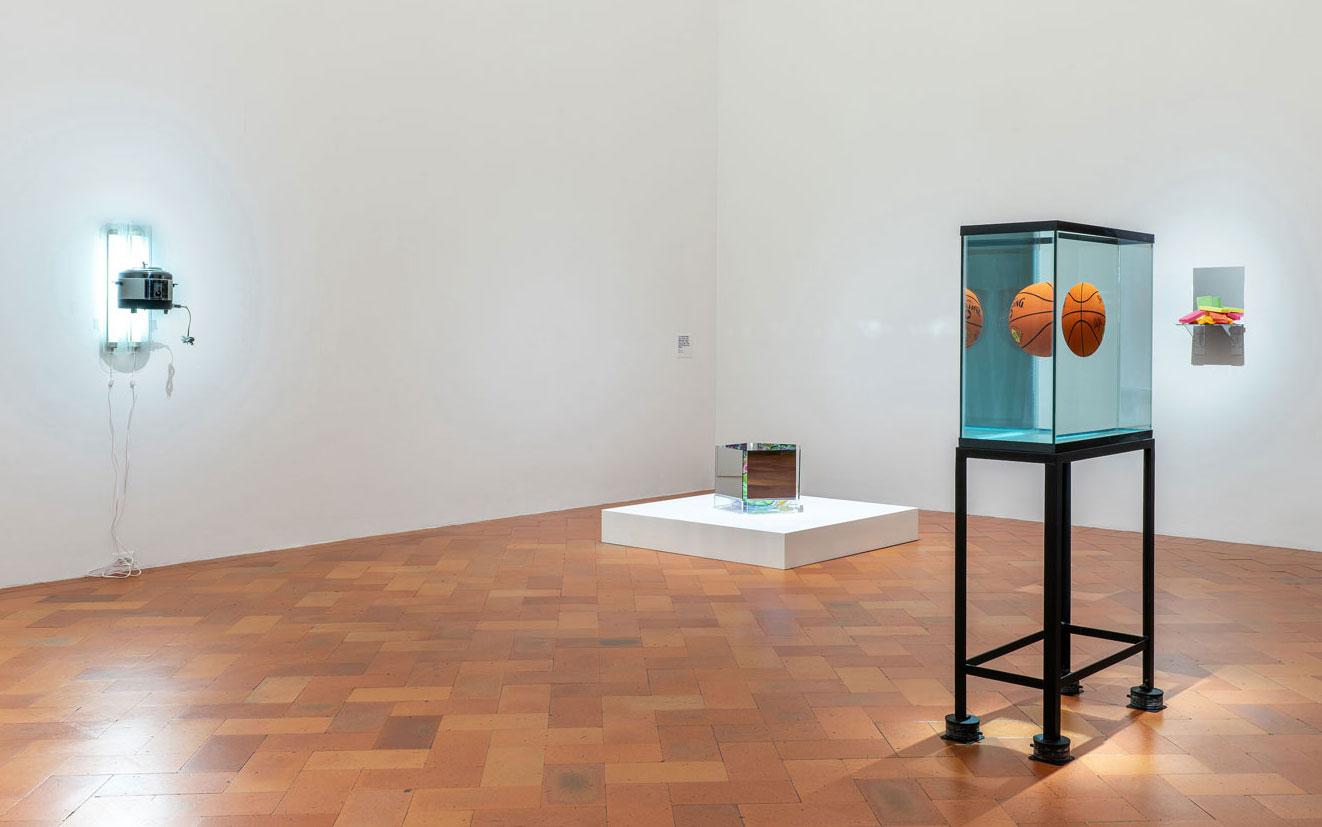

Jeff Koons, Balloon Monkey (Blue), 2006-2013. Installation view of the exhibition ’Shine’ at Palazzo Strozzi, Florence.

We gawp like magpies at his clusters of shiny things: polished stainless steel casts of balloon dogs, bloated, faceless rabbits, and gazing balls perched on, in and around iconic examples of classicalism.

The more we look, the more Koons’ work looks at home within the storied walls of the Palazzo Strozzi, where he is currently staging a major solo show, ‘Shine’. The Florentine building – whose foundations were laid in 1489 – sustains part of the Renaissance’s bloodstream, and the Renaissance flows freely and abundantly in that of Koons.

Curated by Arturo Galansino and Joachim Pissarro and spanning 40 years of work, ‘Shine’ offers Koons’ greatest gleaming hits, but with a renewed luminosity, potential and intensity. It’s an invitation to look back, look ahead, and look hard.

Jeff Koons, Sacred Heart (Magenta/Gold) 1994-2007 (left); Seated Ballerina, 2010-2015 (right). Installation view of the exhibition ’Shine’ at Palazzo Strozzi, Florence.

Wallpaper*: Where are you as we speak?

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Jeff Koons: I’m in New York City, in my studio on 10th Avenue and 36th Street. I’m sitting in a small office where I keep my paperwork and books for the projects I’m working on. The studio has two floors, different to the previous studio in Hudson Yards, which has now been developed. Right outside my office is my 3D department, which is where most of my work is generated today.

W*: When did you switch from creating in analogue to digital?

JK: Years ago I made everything myself: my vacuum cleaner pieces, even the stands of the One Ball Total Equilibrium Tank. I would have somebody do the welding but I would do all the finishing work.

I started working digitally around 1994. Elephant was the first piece where I took the information to a computer to manufacture the artwork. Since then, I’ve relied more and more on different types of scanning: white light scanning, blue light scanning, CAT scanning to print images and create models or to mill a material. So instead of building up, we’re taking away.

W*: Your work seems to lend itself well to digital production, reproduction and tweaking.

JK: I always doodle. So if I have an idea, or I’m thinking about something, I make a doodle. And I make mental notes. Technology is only a tool and there’s no art in that technology; it’s just a vehicle for you to realise ideas more clearly. And if it can help you be more precise in your communication of those ideas, fantastic.

There’s no real newness beyond the novelty of something. Within art, what presents itself as shocking and fresh is actually quite old.

Jeff Koons, One Ball Total Equilibrium Tank (Spalding Dr. JK 241 Series), 1985 (front right). Installation view of the exhibition ’Shine’ at Palazzo Strozzi, Florence.

W*: I read your piece in the Financial Times. I’d never really thought about relating the Renaissance so closely to how we live right now. Maybe we’re overdue a Renaissance renaissance, or at least thinking about it that way.

JK: I agree completely. There were always new technologies, whether it’s the wheel, or irrigation, or fluid dynamics. We continue to readapt, but I do think that the time we live in is like a Renaissance. All of us have the most complete history of humankind at our fingertips.

W*: It’s interesting psychologically. If you can’t remember the name of an artist now, all you have to do is Google. Before, you’d have to delve deep into your brain for that information.

JK: You’d have to go to the library or call a friend, or you’d have to think about something for a lot longer. But these things are having a huge impact on our society and our ability to be generous. What’s important now is that as human beings, we can open ourselves up to life experience.

I remember after having a really very successful exhibition, my ‘Banality’ show in 1988, a journalist asked me, ‘Jeff, aren’t you afraid it’s gonna leave you?’ And I thought, ‘leave me?’ You know, this big success as a young artist. I started to think about what I could do and realised the only thing that any of us can do is to trust in ourselves. So the work in ‘Shine’ at Palazzo Strozzi is dealing with this aspect of transcendence: what’s relevant in life is the essence of our potential.

In the Renaissance, I think people were opening themselves up. They had these technologies, but there was something else that brought along a sense of curiosity.

Jeff Koons, Gazing Ball (Apollo Lykeios), 2013. Installation view of the exhibition ’Shine’ at Palazzo Strozzi, Florence.

W*: Is that what you most admire about Renaissance art, how it captured humanity in a way that nothing had before?

JK: I think they had a great curiosity and great respect for the past. When the Florentines and Romans were unearthing a lot of ancient Greek and ancient Roman pieces, this had a huge impact on society; coming into contact with ideals of the ancient past.

W*: I was at your show at the Ashmolean in 2019, and I suppose there are parallels between that show and ‘Shine’: the meeting of the ancient and new, reflection and the viewer ‘activating’ the work.

JK: I was very proud of that exhibition [at the Ashmolean]. I loved it.

I started making art as a young kid and would always draw and paint, and I never knew what art was. When I was in art school and learned about art history, I started to realise how it connects all the human disciplines. When I graduated from art school and started to really focus on my work, there were moments I would create things that were so powerful to me that they would overtake me physically. I’d have to go out and have some beers just to come down from the experience of putting a pink rabbit beside an inflatable flower on four mirrored panels. The colours were so bright; it was such an intense experience. That’s when it started to become greater than myself.

Even though I try to make work that’s very much about the viewer, and I know the viewer finishes it, I’m still very selfish. I want to make works that really move me and perform like a drug in intensity.

RELATED STORY

W*: Otherwise, what’s the point?

JK: Correct. In more primitive times, it’s like going out on a hunt. Originally, you would come home with a hare, and that’s enough for you. But after a while, you realise, ‘Oh, wait, I want to bring back a mammoth’. And so you go hunting a mammoth. That’s what I like to do today.

Jeff Koons, Balloon Dog (Red),1994-2000. Installation view of the exhibition ’Shine’ at Palazzo Strozzi, Florence.

W*: It’s quite difficult to convey this idea of ‘Shine’ over a screen. In the last two years, have you reflected on the importance of in-person experiences in your work?

JK: The pandemic is a horrible experience. We’ve all lost friends, and we know many people who have lost family members. But if anything was positive it would have been the intimacy that we were able to have with our friends and family. Unbelievable intimacy, it’s hard to let go of that. That was quite special.

At the same time, when we’re faced with moments where we have time to reflect; we go over what’s relevant in life, and what’s important. In ‘Shine’, I’m trying to bring to the forefront the way I view art, the way it can function, and be of true value to people.

People that speak about art today, and the many different publications that write about it, just end up speaking about all the superficial aspects of it, instead of ‘here’s this transcending power that lets us come into contact with the essence of our potential’.

Installation view of Jeff Koons’ exhibition ’Shine’ at Palazzo Strozzi, Florence, including Balloon Venus Lespugue (Red), 2013-2019 (left).

W*: Is that essence something we’ve lost sight of? Do you think it was more present in previous movements, like Dadaism or Surrealism?

JK: When you mention Dada or the Surrealists, I get excited, because I always want to participate and be part of the dialogue; to be in a room and talk about art.

People feel very intimidated by my work, but it always tries to empower the viewer and let them know that they are perfect. We’re all perfect in our being. Our past can’t be anything other than what it is, it’s not going to change. But we can change from this moment forward.

I know from my own experience of where I came from, what my past has been, what things I survived, that it’s about real experience. So that’s why I would make works like Ushering in Banality, Puppy or Balloon Dog. It’s about human history.

People can’t achieve transcendence and reach a higher consciousness without really being open, without appreciating and loving other people. And as soon as that happens, you’re able to find something greater than the self, you’re able to envision that there’s a place to go, there’s a path, there’s a vastness, there’s the ability to transcend.

W*: So you feel the only way to transcend is through relationships with others?

JK: It’s finding something greater than the self, getting out of the self and being able to give it up to something. I mean, you hear about love all the time in our culture: love, love, love, love! Love, in the abstract form, is giving it up to something outside the self.

Installation view of Jeff Koons’ exhibition ’Shine’ at Palazzo Strozzi, Florence.

W*: Have there been times when you’ve reached particularly intense moments of transcendence?

JK: When I’m really focusing on my work. I spoke before about trusting in the self, then very intensely focusing on those interests. Everything becomes very, very objective, everything seems familiar, you are very aware of the abundance of information around you.

I try to always practise the removal of judgment. Judgment only creates anxiety, it only segregates.

W*: Don’t you have to retain a certain level of judgment for quality control?

JK: I don’t really think of that as judgment. I think that there are things that have a sense of significance at a certain time. I may want to bring something in a certain direction, and that doesn’t mean that the other direction isn’t any good, but right at this moment, for this piece, I’d like to bring it there. I like to be open to everything, and when you’re open everything, you realise everything is so stimulating and everybody looks familiar.

Jeff Koons, Rabbit, 1986. Installation view of the exhibition ’Shine’ at Palazzo Strozzi, Florence.

W*: What’s the most challenging project you’ve worked on?

JK: There have always been challenges in creating different projects and different bodies of work. Sometimes it can be having the right technology or level of craft at that moment, or it could be financial, it could be all different aspects.

I just follow my intuition and my interests. Usually, before I make anything, I’ve been thinking about it for at least two years. I want to be sure that when I do make something, I’m using the opportunity I have to its fullest; that it’s something I really want to make. Then I commit to doing it. I thought about the Gazing Ball work for over three decades. When I made my Rabbit, if you look in the head of Rabbit, I was really thinking about a gazing ball.

I wanted something very pure, and finally, I made the plaster casts and the paintings in the Gazing Ball series. That wasn’t struggling, that was just thinking about the most ideal situation.

W*: Do you have a favourite piece of Renaissance art?

JK: I’m always very moved by Michelangelo’s Florentine Pietà. It deals with itself, but it also goes into all these different areas of history and theology. And Titian’s Pastoral Concert, that’s not in Florence, but it’s amazing. Raphael’s work, and in Florence, Uccello’s painting The Battle of San Romano, all the Botticellis, the Donatellos.

We just had an amazing exhibition in New York at The Metropolitan Museum based on the Medici family. The Bronzino paintings are so animated, so colourful, and so contemporary, though I know it’s corny to say. They have a Disney quality, a Pixar quality.

I think people respected the idea of making a mark in the Renaissance, as though they were recording the history of what it means to be human, which we take for granted today. We don’t have to record, we don’t have to synthesise what an experience is really like, but they synthesised it, they personally took on that responsibility.

Jeff Koons, Gazing Ball (Tintoretto The Origin of the Milky Way) (2016). Installation view of the exhibition ’Shine’ at Palazzo Strozzi, Florence.

Jeff Koons, ‘Shine’, until 30 January 2022, Palazzo Strozzi, Florence, palazzostrozzi.org

ADDRESS

Piazza degli Strozzi

50123 Firenze FI

Harriet Lloyd-Smith was the Arts Editor of Wallpaper*, responsible for the art pages across digital and print, including profiles, exhibition reviews, and contemporary art collaborations. She started at Wallpaper* in 2017 and has written for leading contemporary art publications, auction houses and arts charities, and lectured on review writing and art journalism. When she’s not writing about art, she’s making her own.

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss

-

Remembering Oliviero Toscani, fashion photographer and author of provocative Benetton campaigns

Remembering Oliviero Toscani, fashion photographer and author of provocative Benetton campaignsBest known for the controversial adverts he shot for the Italian fashion brand, former art director Oliviero Toscani has died, aged 82

By Anna Solomon

-

Distracting decadence: how Silvio Berlusconi’s legacy shaped Italian TV

Distracting decadence: how Silvio Berlusconi’s legacy shaped Italian TVStefano De Luigi's monograph Televisiva examines how Berlusconi’s empire reshaped Italian TV, and subsequently infiltrated the premiership

By Zoe Whitfield

-

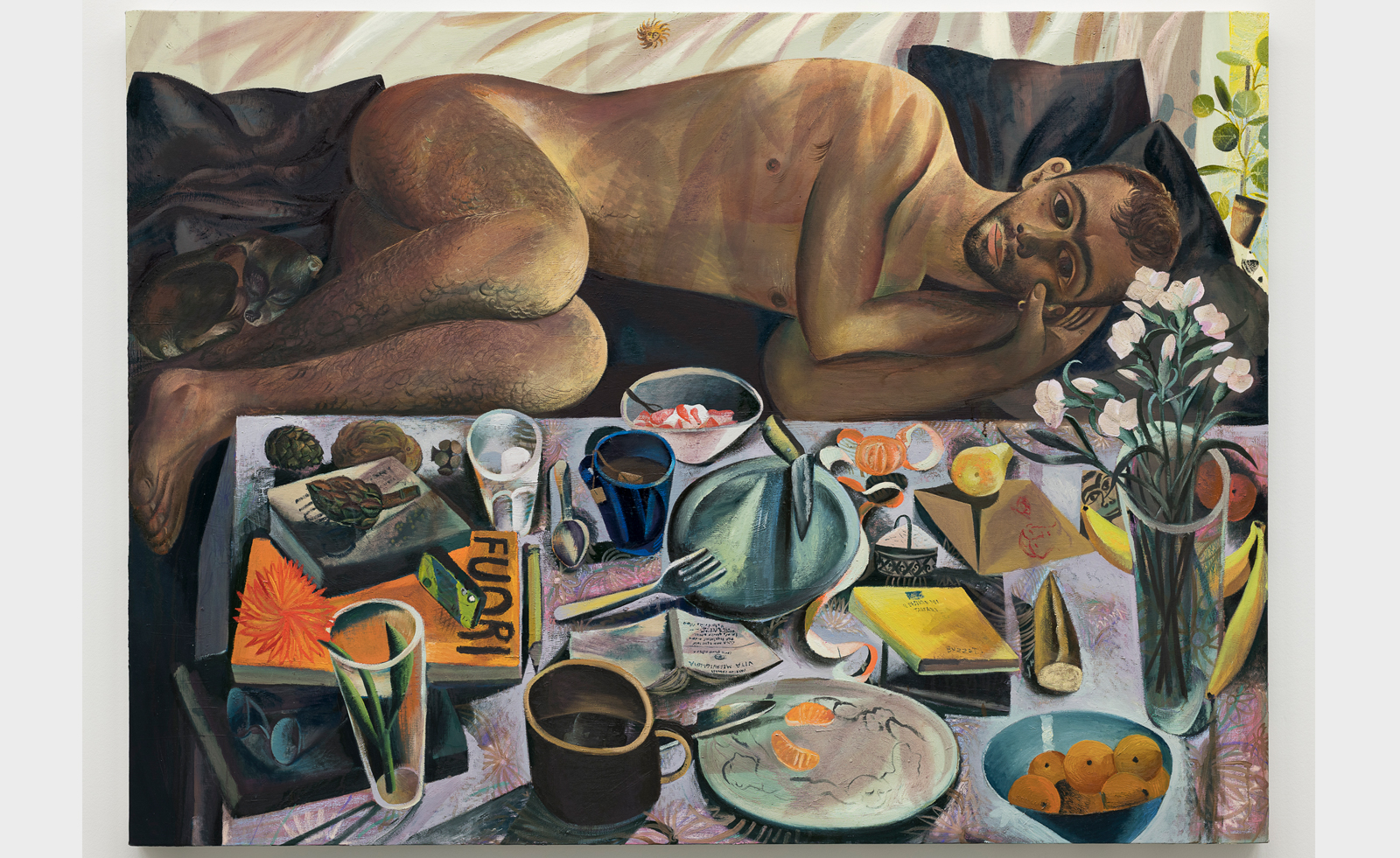

Louis Fratino leans into queer cultural history in Italy

Louis Fratino leans into queer cultural history in ItalyLouis Fratino’s 'Satura', on view at the Centro Pecci in Italy, engages with queer history, Italian landscapes and the body itself

By Sam Moore

-

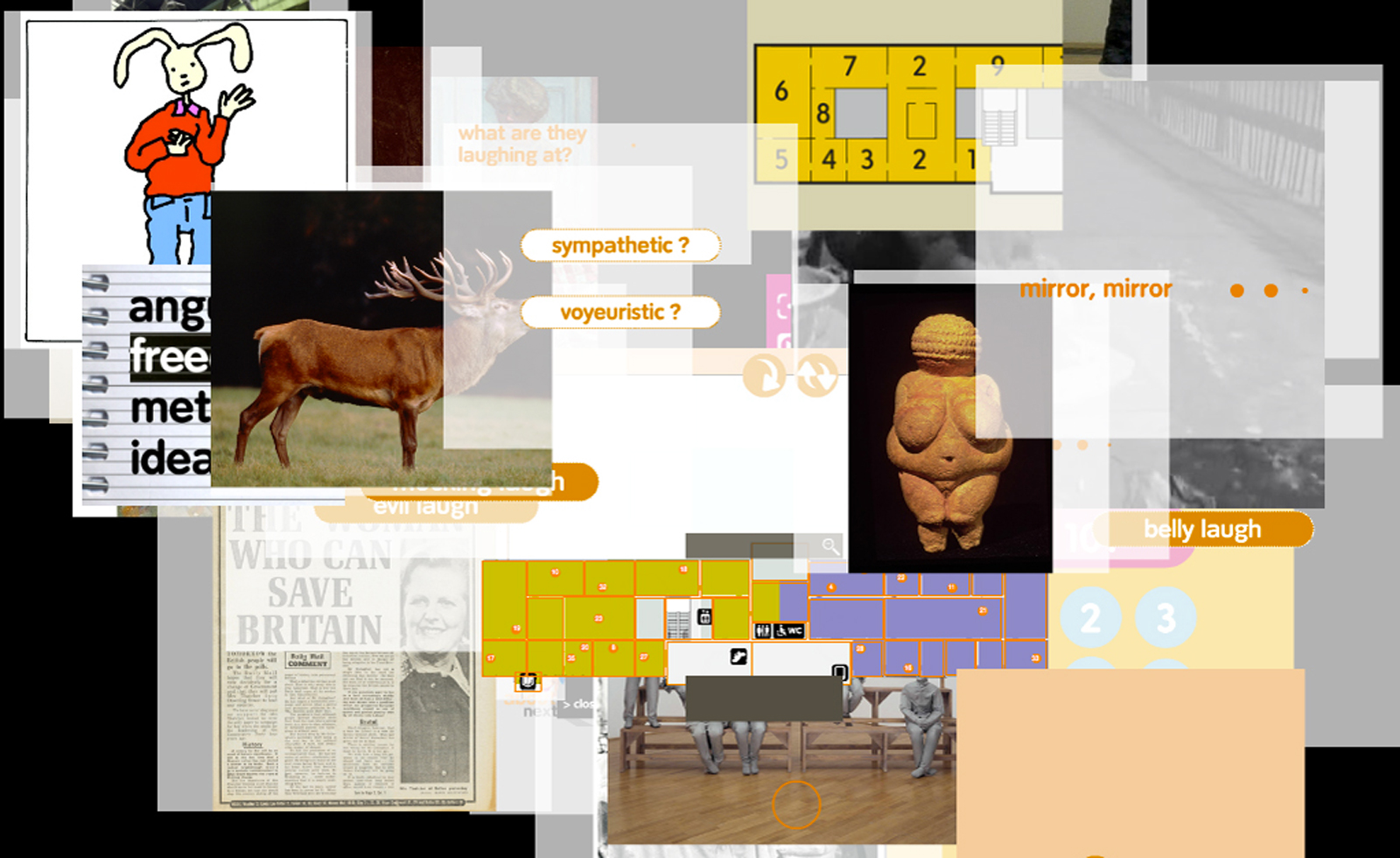

‘I just don't like eggs!’: Andrea Fraser unpacks the art market

‘I just don't like eggs!’: Andrea Fraser unpacks the art marketArtist Andrea Fraser’s retrospective ‘I just don't like eggs!’ at Fondazione Antonio dalle Nogare, Italy, explores what really makes the art market tick

By Sofia Hallström

-

Jeff Koons’ art has landed on the moon with Odysseus

Jeff Koons’ art has landed on the moon with Odysseus‘Jeff Koons: Moon Phases’ is on the Odysseus lunar lander and due to make a giant NFT leap for the artist, having landed on Thursday 22 February 2024

By James Gurney

-

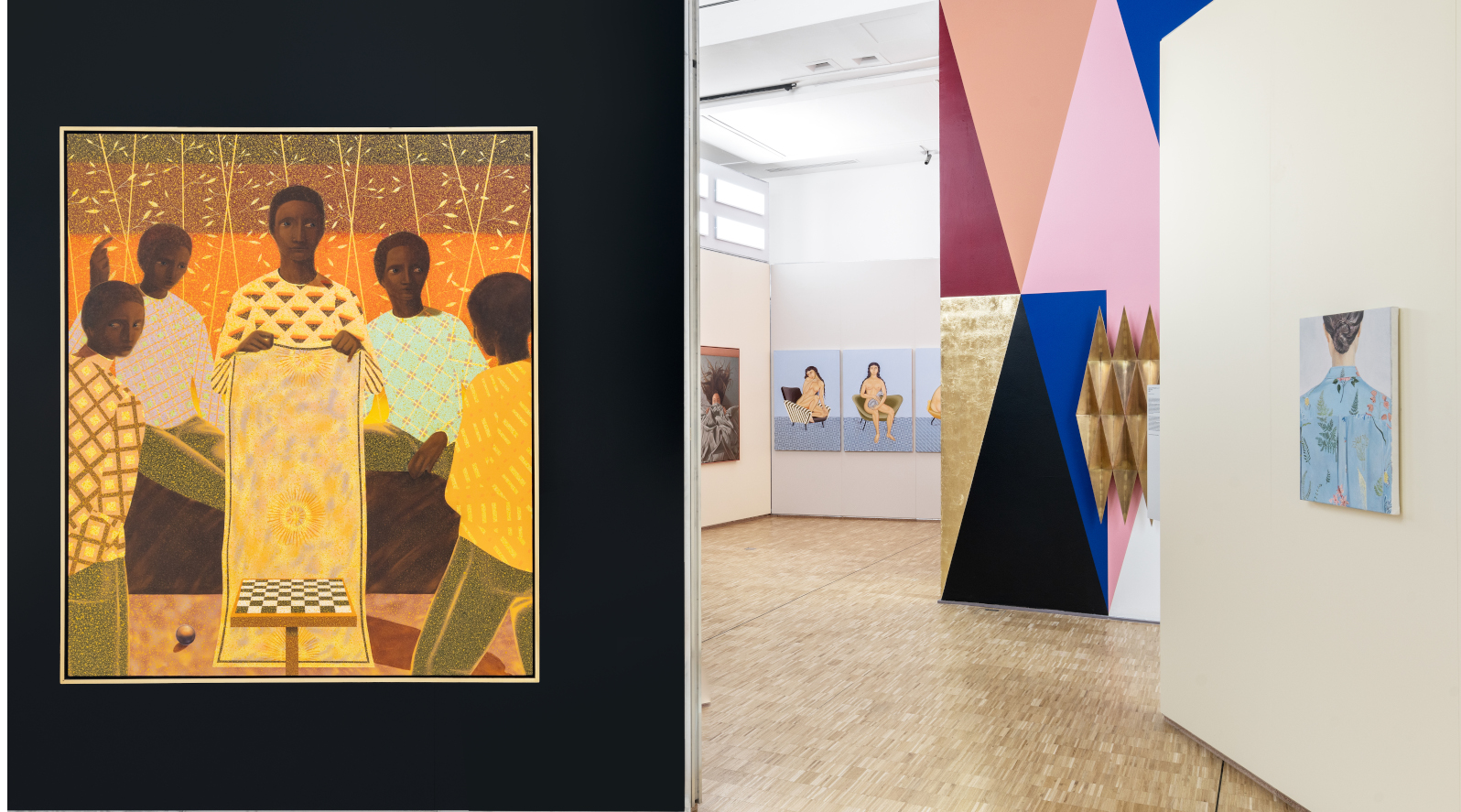

Triennale Milano exhibition spotlights contemporary Italian art

Triennale Milano exhibition spotlights contemporary Italian artThe latest Triennale Milano exhibition, ‘Italian Painting Today’, is a showcase of artworks from the last three years

By Tianna Williams

-

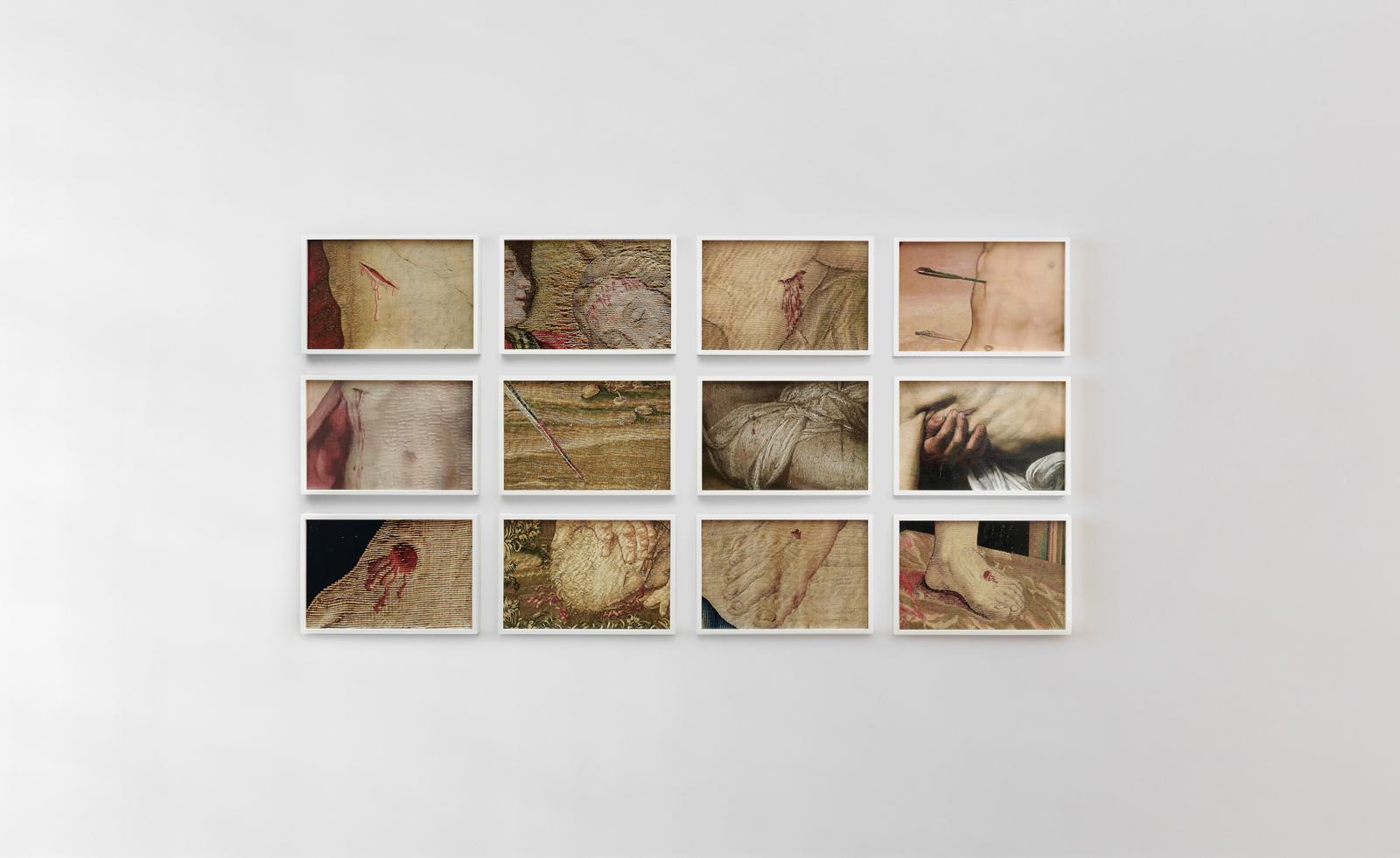

Walls, Windows and Blood: Catherine Opie in Naples

Walls, Windows and Blood: Catherine Opie in NaplesCatherine Opie's new exhibition ‘Walls, Windows and Blood’ is now on view at Thomas Dane Gallery, Naples

By Amah-Rose Abrams

-

Raffaele Salvoldi stacks hundreds of marble blocks for dazzling Milan installation

Raffaele Salvoldi stacks hundreds of marble blocks for dazzling Milan installationFor a Milan Design Week 2023 installation, Italian artist Raffaele Salvoldi teams up with marble brand Salvatori to create architectural sculptures comprising hundreds of marble blocks

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith