August Sander’s ambitiously truthful character studies capture a startling humanity

In his Small History of Photography (1931), Walter Benjamin wrote – in response to August Sander’s book Face of our Time (1929) – that the rapidly changing world made ‘the sharpening of physiognomic perception a vital necessity’.

This problematic idea – that the physical body can tell us something about a person’s inner world – is still part of our understanding of portrait photographs, no matter how aware we are now of the camera’s ability to deceive us. The attempt to classify people according to their appearance, demeanour or physiognomy, as Sander tried to do, may be difficult to grapple with today, but he believed in the sociological importance of photography as part of a modernising society – perhaps more than any other photographer in the 20th century.

His vast archive of people and landscapes reached more than 40,000 images during his lifetime though only about 11,000 survived (some 30,000 negatives were destroyed in an accidental fire at his studio in Cologne after the end of World War Two).

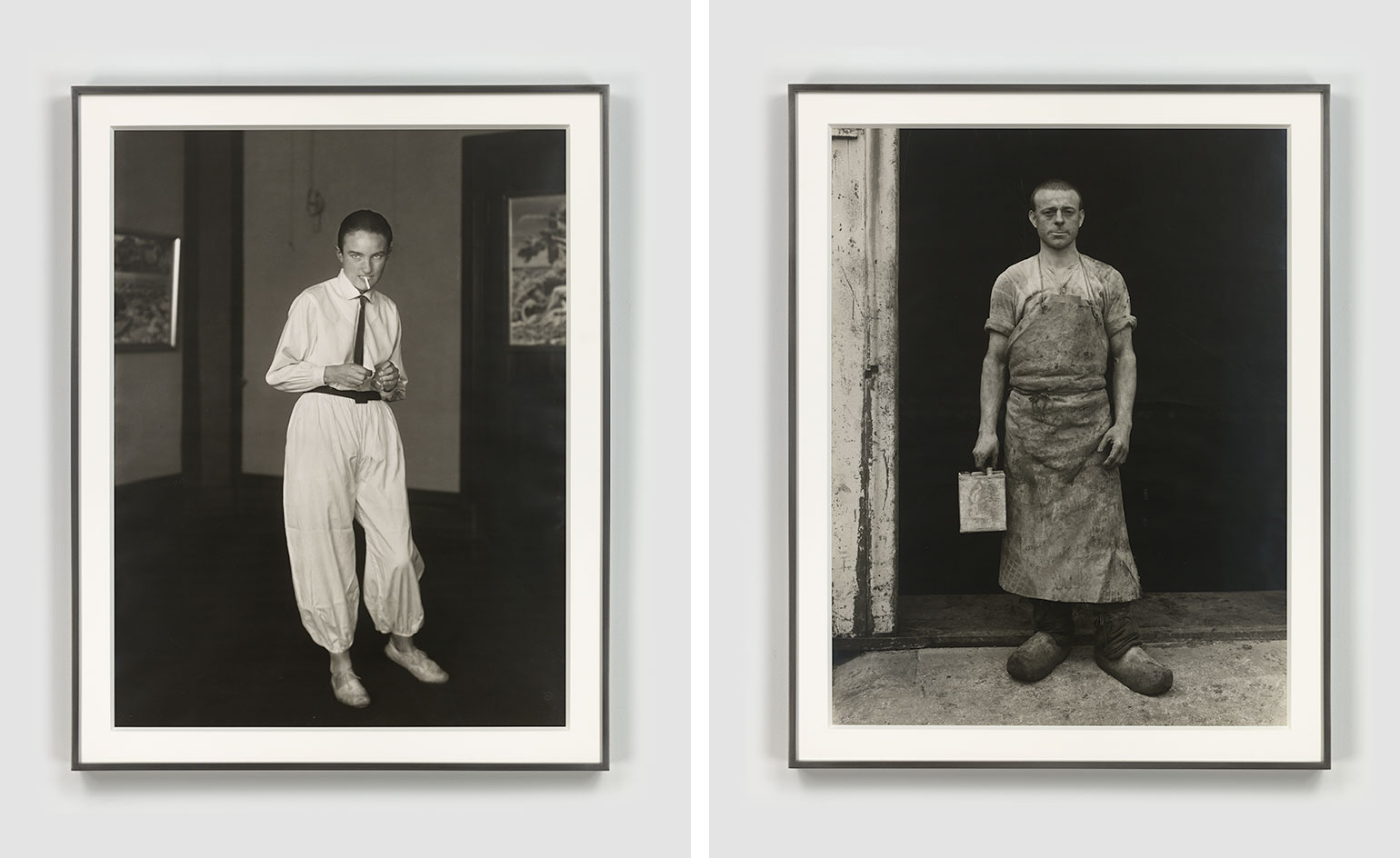

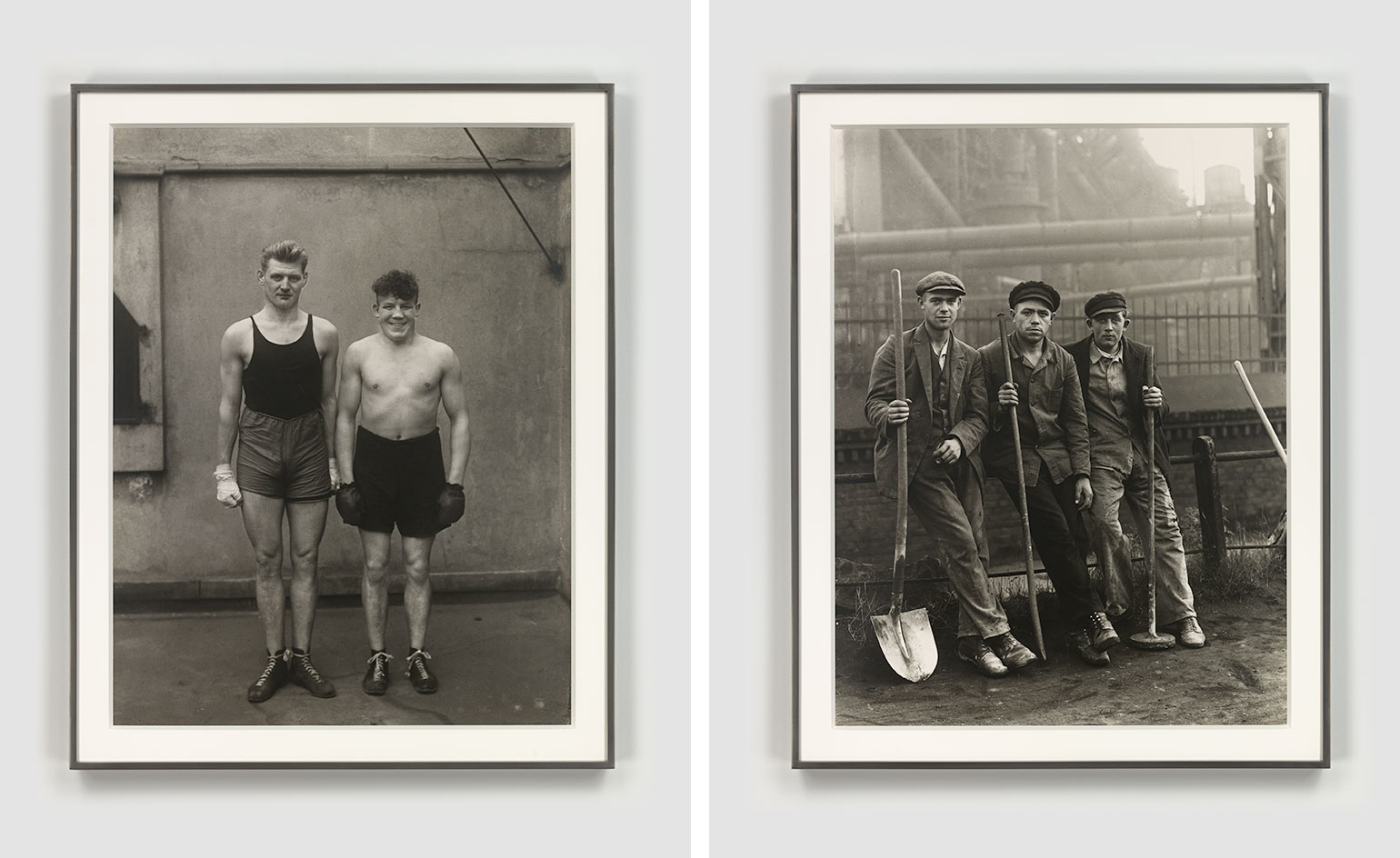

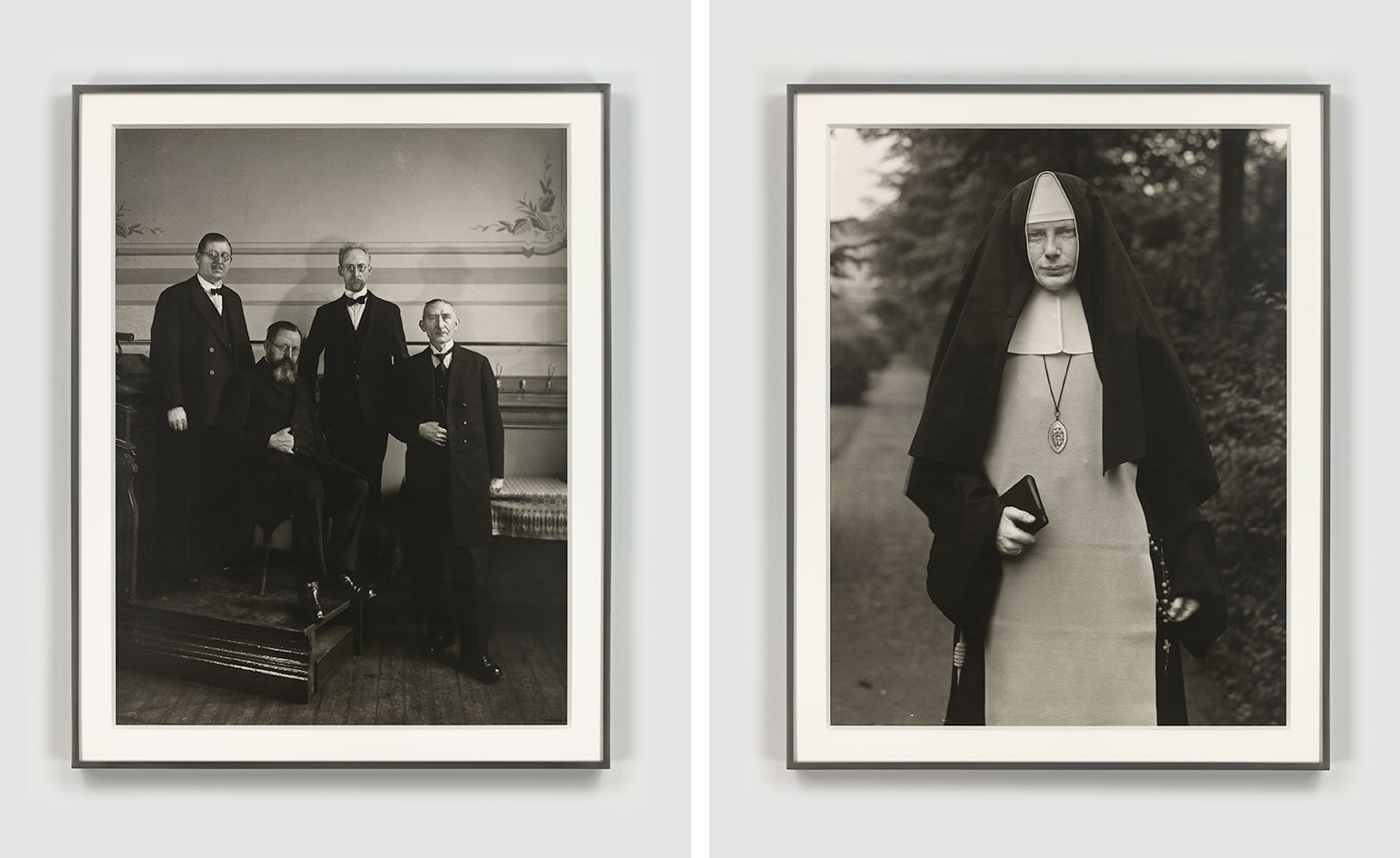

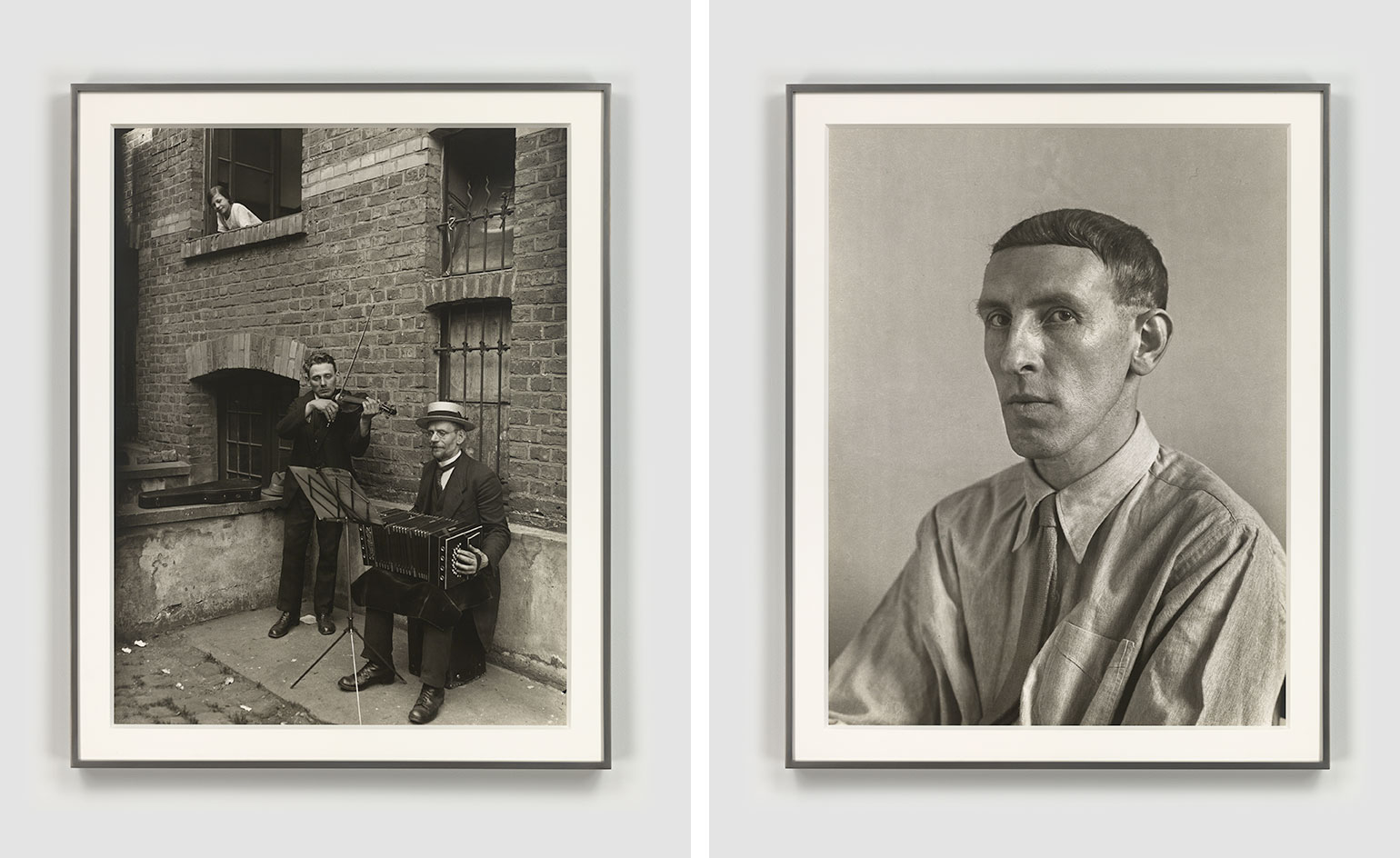

Sander’s conviction in the power of a photograph is apparent in an exhibition of 40 works by the celebrated German photographer at Hauser & Wirth’s 69th Street New York outpost. Among these are individual portraits in large format: such as Sportflieger (Aviator) (1920), Lackarbeiter (Varnisher) (1930), and group shots such as Boxer (1929), and The Farming Couple (1912), that assert important aspects of Sander’s style: subjects look directly at the camera, and are depicted in a straightforward, naturalistic setting, dressed in the typical clothes of their class or profession.

The pictures are printed larger than in Sander’s lifetime, a decision originally made by his son Gunther, who reproduced them on this scale for an exhibition in 1972. Their size emphasises another intrinsic part of Sander’s photography: detail.

Whether it’s a hand gesture, the glint of an eye, the crevice that makes a facial expression, or the fold of a fabric, seeing Sander supersize shows how he observed these little things as shaping a person’s identity. This adherence to ‘reality’ was a stark departure from trends in photography of the day – Sander was interested in observation, his lens a way to probe at his surroundings.

As John Berger would write, years after Benjamin’s reflections on Sander, in his essay The Suit and the Photograph, these details – how clothes sit on the body, the subjects’ postures and shape – incisively comment on class. Though there is an insistence on individuality in Sander’s portraits of people, he did seek to give a representational idea about each social strata.

His proximity to many of his subjects – he knew many of them personally, or spent time getting to know them and their way of life – allowed him to take this liberty with their identity. This artistic interpretation factored into his approach in his most important project – People of the 20th Century (1927), socioeconomic portraits of a nation. Each image may have its own story to tell, but it’s the viewer that has to create that narrative, and confront the paradigms he presents.

The people in these pictures are no longer alive and the world they once inhabited has radically changed. The ambitious ‘truth’ in Sander’s images today is difficult: but it doesn’t detract from the startling humanity of the people he left behind in his photographs.

Bauernkinder (Farm Children), c1913; and Bauern aus der Leuscheid (Farmers from Leuscheid), 1926

Boxer (Boxers), 1929; and Strassenarbeiter im Ruhrgebiet (Workmen in the Ruhr), c1928

Stadtmissionare (Urban Missionaries), c1931; and Nonne (Nun), 1921

Strassenmusikanten (Street Musicians), c1922-1928; and Maler [Heinrich Hoerle] (Painter [Heinrich Hoerle]), 1928

Kretin (Cretin), 1924; and Bettlerehepaar, (Beggars, Married Couple), 1928

INFORMATION

‘August Sander’ is on view until 17 June. For more information, visit the Hauser & Wirth website

ADDRESS

Hauser & Wirth

32 East 69th Street

New York NY 10021

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Charlotte Jansen is a journalist and the author of two books on photography, Girl on Girl (2017) and Photography Now (2021). She is commissioning editor at Elephant magazine and has written on contemporary art and culture for The Guardian, the Financial Times, ELLE, the British Journal of Photography, Frieze and Artsy. Jansen is also presenter of Dior Talks podcast series, The Female Gaze.

-

Click to buy: how will we buy watches in 2026?

Click to buy: how will we buy watches in 2026?Time was when a watch was bought only in a shop - the trying on was all part of the 'white glove' sales experience. But can the watch industry really put off the digital world any longer?

-

Don't miss these art exhibitions to see in January

Don't miss these art exhibitions to see in JanuaryStart the year with an inspiring dose of culture - here are the best things to see in January

-

Unmissable fashion exhibitions to add to your calendar in 2026

Unmissable fashion exhibitions to add to your calendar in 2026From a trip back to the 1990s at Tate Britain to retrospectives on Schiaparelli, Madame Grès and Vivienne Westwood, 2026 looks set to continue the renaissance of the fashion exhibition

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week'Tis the season for eating and drinking, and the Wallpaper* team embraced it wholeheartedly this week. Elsewhere: the best spot in Milan for clothing repairs and outdoor swimming in December

-

Nadia Lee Cohen distils a distant American memory into an unflinching new photo book

Nadia Lee Cohen distils a distant American memory into an unflinching new photo book‘Holy Ohio’ documents the British photographer and filmmaker’s personal journey as she reconnects with distant family and her earliest American memories

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekIt’s been a week of escapism: daydreams of Ghana sparked by lively local projects, glimpses of Tokyo on nostalgic film rolls, and a charming foray into the heart of Christmas as the festive season kicks off in earnest

-

Ed Ruscha’s foray into chocolate is sweet, smart and very American

Ed Ruscha’s foray into chocolate is sweet, smart and very AmericanArt and chocolate combine deliciously in ‘Made in California’, a project from the artist with andSons Chocolatiers

-

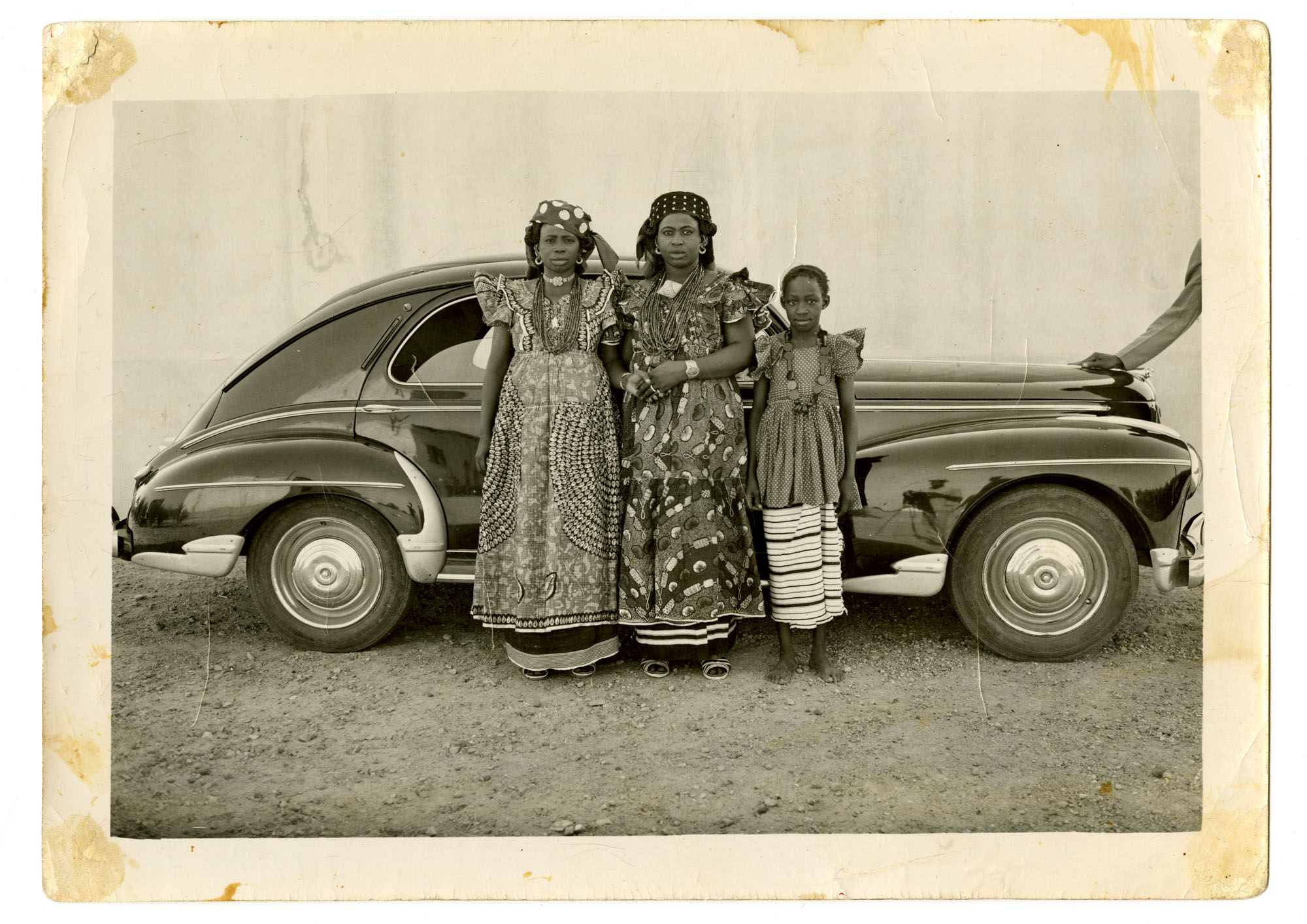

Inside the work of photographer Seydou Keïta, who captured portraits across West Africa

Inside the work of photographer Seydou Keïta, who captured portraits across West Africa‘Seydou Keïta: A Tactile Lens’, an exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, celebrates the 20th-century photographer

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekFrom sumo wrestling to Singaporean fare, medieval manuscripts to magnetic exhibitions, the Wallpaper* team have traversed the length and breadth of culture in the capital this week

-

María Berrío creates fantastical worlds from Japanese-paper collages in New York

María Berrío creates fantastical worlds from Japanese-paper collages in New YorkNew York-based Colombian artist María Berrío explores a love of folklore and myth in delicate and colourful works on paper

-

Out of office: the Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: the Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekAs we approach Frieze, our editors have been trawling the capital's galleries. Elsewhere: a 'Wineglass' marathon, a must-see film, and a visit to a science museum