Back to black: Edmund de Waal plays with dark glazes in new body of work

‘This is a huge departure, quite a scary one, actually,’ says Edmund de Waal of ‘Ten thousand things’, his upcoming solo show at Gagosian Beverly Hills. For a world-renowned ceramicist who threw his first pot at the age of five – and who’s since installed his elegant and haunting ceramic-filled vitrines beneath the pavement outside the University of Cambridge and atop the cupola of the Victoria & Albert Museum — that’s saying quite a lot. ‘It’s come out of a lengthy period of thinking about architecture and music and all kinds of other things, so it’s a really big show for me.’

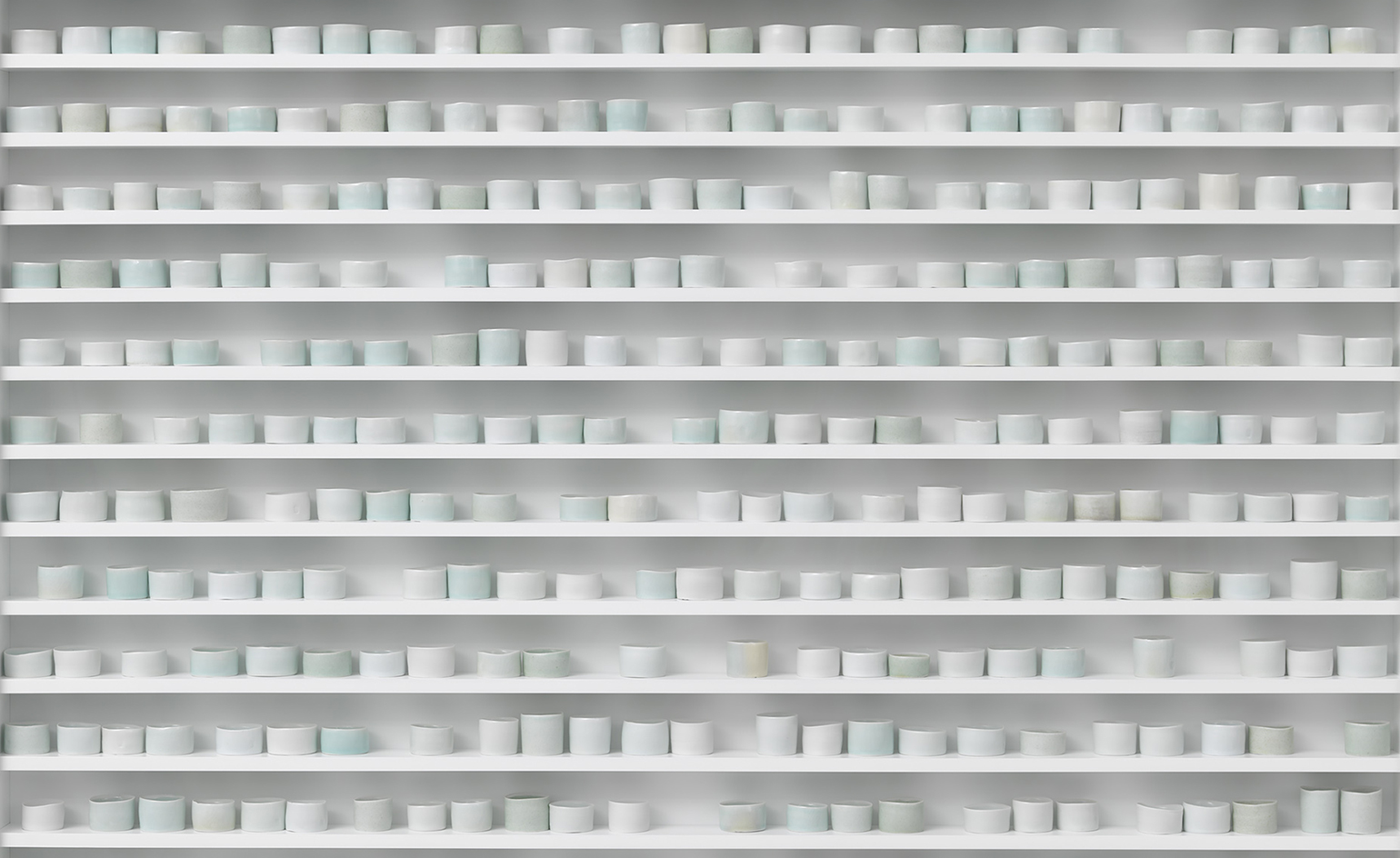

For those who are familiar with de Waal’s work — mainly white, black, sometimes colored vitrines, carefully staged with Japanese-influenced pots, plates or cups that are created in an assembly-line-like fashion at his white-walled, gallery-sized South London studio — the format might not, at first glance, seem particularly groundbreaking. Even his use of black porcelain, which he showed at his 2013 debut with Gagosian in New York, and again at his 2010 solo at London’s Alan Cristea Gallery, isn’t entirely novel.

But over the last two and a half years, the artist has been experimenting with black glazes in an attempt to find ‘new shadows, gaps and spaces in his work’, he says. ‘And what those can do at scale.’

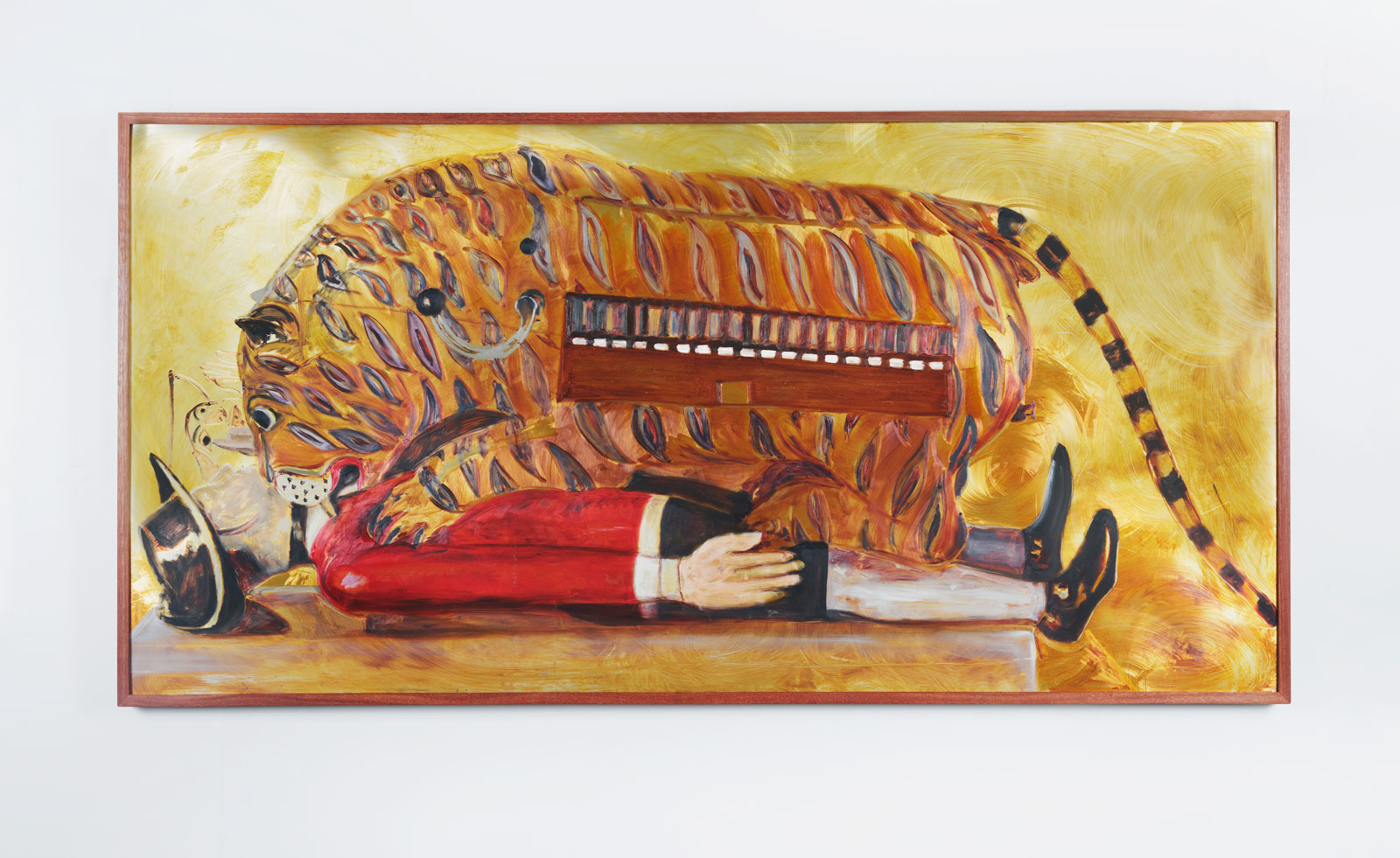

The decision to explore this darker terrain — in the form of hundreds of black vessels made with copper-and-tin-flecked glazes in dialogue with hunks of raw materials (from Cor-Ten steel and gold, to lead and plaster) all framed within various black aluminum-and-glass vitrines — began as a response to the revolutionary scores of John Cage, particularly his mid-century masterpiece The ten thousand things.

For de Waal, Cage’s brief residency in the early 1930’s at Rudolph Schindler’s King’s Road House in West Hollywood (now home to the MAK Center for Art and Architecture) was the starting point. ‘I’ve had a photograph of the Schindler on my wall for about 20 years,’ says de Waal, who hasn’t actually been back to the house for over a decade. Still, this meeting of modernist mavericks, argues de Waal, provided a mind-clearing platform that allowed Cage’s more iconic sonic experimentations to take shape.

‘The Schindler House with its concrete and timber coming together in unexpected ways and Cage being so decidedly radical about not letting anything lie – to free yourself from what you know, they seem to be different things. But they’re actually very similar in that they’re both experimenting in public. That’s really what this is about,’ says De Waal, who is making, glazing and placing his works in a looser, more intuitive fashion for his own public experiment in Beverly Hills. ‘I just picked up these blocks of Cor-Ten steel and thumped them down very rhythmically, in a very random way. It’s as close as I’ve ever gotten to doing a musical score.’

In years past, De Waal admitted his installations had a borderline over-determinacy about them, but claims his newfound freedom is ‘a lot more fun,’ he says. ‘Of course it doesn’t always work. In all proper experiments, some things go wrong.’

The exhibition might be seen as a through-the-looking-glass moment for De Waal’s obsession with vitrines. ‘The vitrine is a safe container, where you prevent the diaspora and when I started using vitrines that was the resonant stuff,’ says De Waal. ‘Now it’s much, much more sculptural. It’s an elbows-out kind of relationship between what’s going on with structure and objects.’

At Gagosian, de Waal is revolting against those safety barriers and virtually everything he was chasing in The White Road: Journey Into an Obsession, his new ‘history of brokenness and shards’ that documents recent pilgrimages to Jingdezhen, China, Dresden, Germany and Cornwall, England, the high holy places of porcelain, which has defined his delicate practice for the past three decades.

‘I was living in this obsessive space in my head about white and reading Moby Dick and I was really, really interested in trying to get as close to the first moment of porcelain in the west in Meissen, where they tried for 15 years to make white porcelain and they ended up making black porcelain because they couldn’t figure it out.

'It struck me as this extraordinary, deep metaphor — you’re trying to get to white but you have to go through black,' says De Waal, explaining, 'I don’t do random exhibitions. It’s about a body of work for specific place, a time of year, a quality of light. This exhibition is for LA, a city of exiles and wannabes and experimentation and Schindler and Cage. It seemed to be a very good conjunction to give me a kick to do what I wanted to do.'

Edmund De Waal's 'Ten thousand things', opening today at Gagosian Beverly Hills, explores the artist's interests in black porcelain glazes. Pictured: to speak to you, 2015

The title of the show is a nod to the composer John Cage, whose revolutionary scores were an initial inspiration for de Waal's segue into darker territory. Pictured: black milk, 2014

The exhibition might be seen as a through-the-looking-glass moment for De Waal’s obsession with vitrines. ‘The vitrine is a safe container, where you prevent the diaspora and when I started using vitrines that was the resonant stuff,’ he says. Pictured: a lecture on the weather, 2015

De Waal's interest began with 'trying to get as close to the first moment of porcelain in the west in Meissen, where they tried for 15 years to make white porcelain and they ended up making black porcelain because they couldn’t figure it out'. Pictured: ten thousand things, I-XX, 2015

‘Now it’s much, much more sculptural,' he continues. 'It’s an elbows-out kind of relationship between what’s going on with structure and objects.’ Pictured: ten thousand things, for John Cage, IX, 2015

INFORMATION

’Ten thousand things’ is on view until 18 February. For more information, visit the Gagosian’s website

Photography: Mike Bruce. Courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery

ADDRESS

Gagosian Beverly Hills

456 North Camden Drive

Beverly Hills, California

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss

-

Leonard Baby's paintings reflect on his fundamentalist upbringing, a decade after he left the church

Leonard Baby's paintings reflect on his fundamentalist upbringing, a decade after he left the churchThe American artist considers depression and the suppressed queerness of his childhood in a series of intensely personal paintings, on show at Half Gallery, New York

By Orla Brennan

-

Unlike the gloriously grotesque imagery in his films, Yorgos Lanthimos’ photographs are quietly beautiful

Unlike the gloriously grotesque imagery in his films, Yorgos Lanthimos’ photographs are quietly beautifulAn exhibition at Webber Gallery in Los Angeles presents Yorgos Lanthimos’ photography

By Katie Tobin

-

Desert X 2025 review: a new American dream grows in the Coachella Valley

Desert X 2025 review: a new American dream grows in the Coachella ValleyWill Jennings reports from the epic California art festival. Here are the highlights

By Will Jennings

-

Cowboys and Queens: Jane Hilton's celebration of culture on the fringes

Cowboys and Queens: Jane Hilton's celebration of culture on the fringesPhotographer Jane Hilton captures cowboy and drag queen culture for a new exhibition and book

By Hannah Silver

-

New gallery Rajiv Menon Contemporary brings contemporary South Asian and diasporic art to Los Angeles

New gallery Rajiv Menon Contemporary brings contemporary South Asian and diasporic art to Los Angeles'Exhibitionism', the inaugural showcase at Rajiv Menon Contemporary gallery in Hollywood, examines the boundaries of intimacy

By Aastha D

-

Helmut Lang showcases his provocative sculptures in a modernist Los Angeles home

Helmut Lang showcases his provocative sculptures in a modernist Los Angeles home‘Helmut Lang: What remains behind’ sees the artist and former fashion designer open a new show of works at MAK Center for Art and Architecture at the Schindler House

By Francesca Perry

-

'We need to be constantly reminded of our similarities' – Jonathan Baldock challenges the patriarchal roots of a former Roman temple in London

'We need to be constantly reminded of our similarities' – Jonathan Baldock challenges the patriarchal roots of a former Roman temple in LondonThrough use of ceramics and textiles, British artist Jonathan Baldock creates a magical and immersive exhibition at ‘0.1%’ at London's Mithraum Bloomberg Space

By Emily Steer

-

In ‘The Last Showgirl’, nostalgia is a drug like any other

In ‘The Last Showgirl’, nostalgia is a drug like any otherGia Coppola takes us to Las Vegas after the party has ended in new film starring Pamela Anderson, The Last Showgirl

By Billie Walker