‘Bauhaus: Art as Life’ at the Barbican Art Gallery, London

There's a famous story of the first day of term at the Bauhaus school, when László Moholy-Nagy asked the new intake of students to make something out of a sheet of paper. An hour later he came back to find a profusion of swans, skyscrapers and doilies. He looked disdainfully at them until he came to a student who had simply taken his sheet, folded it in half and stood it up on his desk like a greeting card.

Moholy-Nagy pointed to it, praised it and presented it to the class. This was the one, he said, a design which uses the natural capabilities of paper, its foldability, its strength, its simplicity to create a structure that could only be possible in that one material. It is possibly apocryphal – though it sounds likely – but it embodies a curious contradiction at the heart of the Bauhaus, a cocktail of po-faced asceticism and a kind of self-conscious parody of its own seriousness.

The Bauhaus – currently the subject of a major show at London's Barbican Art Gallery – is remembered as the high-minded, German throbbing brain of modernity, a school which embodied the social, philosophical and aesthetic concerns of a movement which sought to change the world, to create a new language of design for an industrial proletarian age and which actually ended up making art objects for a wealthy and educated bourgeoisie. The seriousness of its founders and leaders, the architects Walter Gropius, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Hannes Meyer, radiates from their portraits. These were serious men, scarred by their experiences in the First World War, and determined to radicalise design.

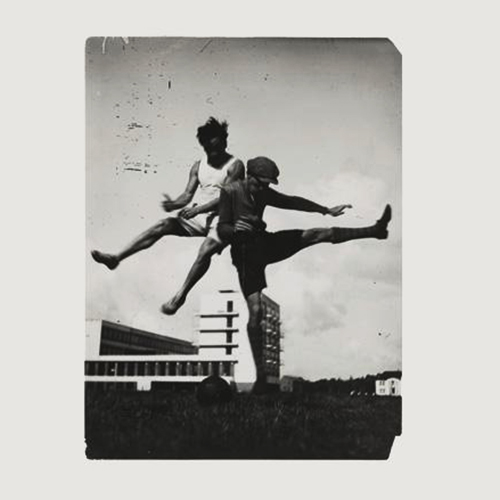

'The jump over the Bauhaus', by T Lux Feininger (1927) capturing sport at the art school.

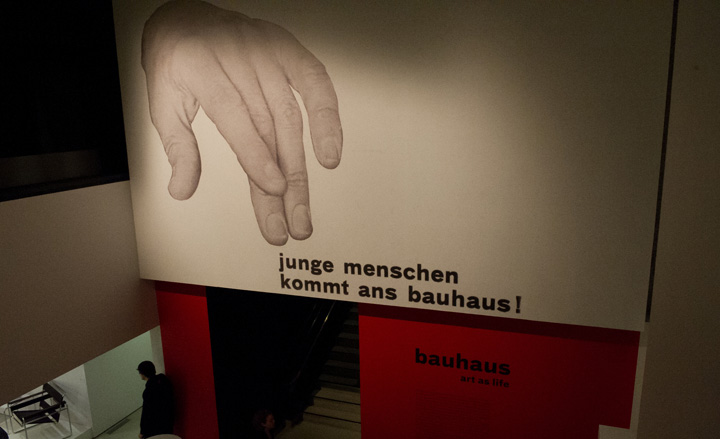

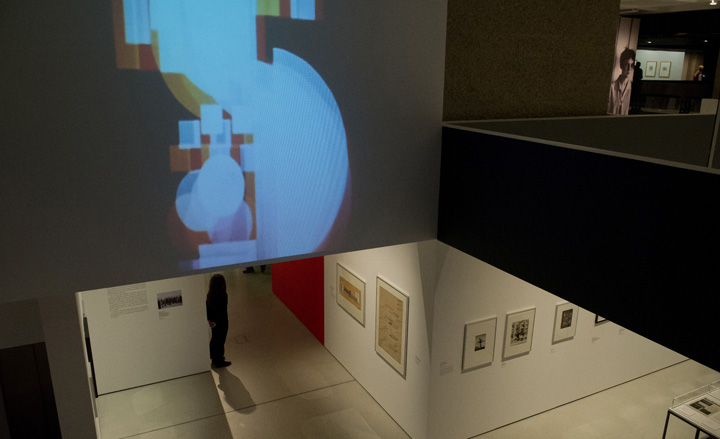

The ‘Bauhaus: Art as Life’ exhibition at the Barbican, designed by architects Carmody Groarke and graphic designers APFEL, attempts to humanise that image of a technocratic will to modernity through a series of personal effects, portraits and stories of the extraordinary range of individuals - many barely known beyond academic circles - who studied at the short-lived design school, which became the most influential the world has ever known.

They also bring to light a little publicised aspect of life at the Bauhaus: humour. The early years of the school were seeped in a strange stew of expressionism, Zoroastrianism and theosophy, and cultish, shaven-headed and robe-clad oddness. It was, at least in its early years, nothing like the modernist machine of myth. Instead it embodied something of the intensity of Weimar culture - it started off in that city, home of the new German republic in the wake of the horrors of the First World War.

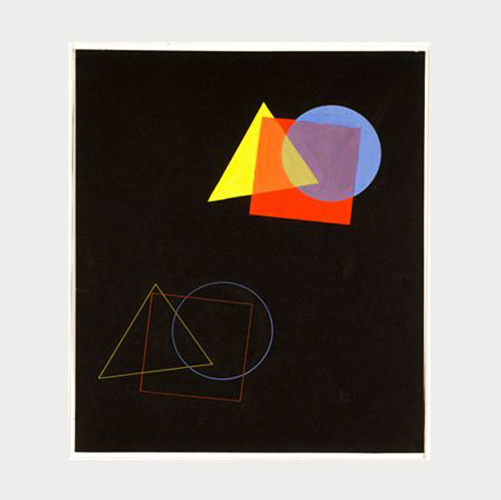

'The spatial effect of colours and forms, from Wassily Kandinsky's course at the Bauhaus Dessau' (1929) by Eugen Batz.

Although it might have slowly become more harshly modernist – notably when it moved to Dessau in 1925 – it always retained as its core elements that Dadaist sense of the ridiculous, an ability to parody its own conventions (in private at least) and a fundamental humanity that was in contrast to its stark design output. It was in the activity of the everyday that this lightness emerged, rather than in the production of design.

Catherine Ince, curator of the Barbican show, says: 'We're trying to look at the Bauhaus as an art school, rather than trying to post-rationalise it into a design moment. We've tried to gather together the more personal items: presents the students made for Gropius, photography of extracurricular activities, invitations and graphics for balls and parties.'

RELATED STORY

Those parties, in particular, must have been extraordinary. There were four 'official' parties each year, elaborate affairs with stage designs by Oskar Schlemmer (head of the theatre workshops); monthly masked balls, for which students made their own, often outrageous, costumes, with music by the Bauhaus' own jazz band; and 'kite parties', in which students competed to make the best kites (some of which were, apparently, too beautiful to actually fly - functionalism, eh?).

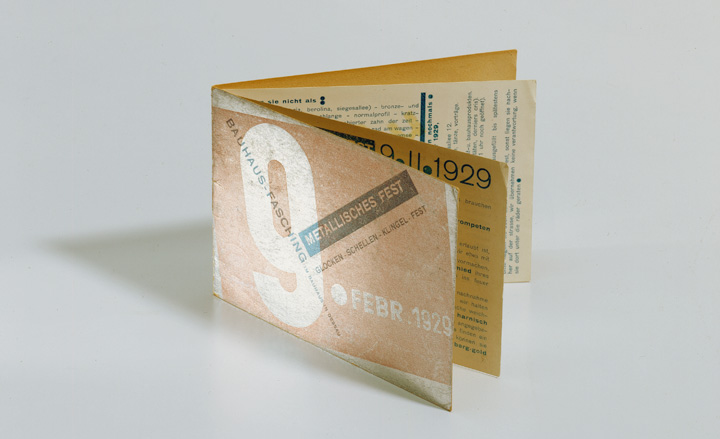

The Barbican is showing Herbert Bayer's 1922 Kite party invitation with the letters arranged as a fluttering tail to a slightly Gilbert and Sullivan caricature, as well as another charming invitation by Rudolf Baschant that looks a little like the Clangers' Soup Dragon. And there were costume parties in which students dressed in geometric outfits, poking fun at the workshops' functionalist production. Some of the costumes were close to the anarchic spirit of Dada, including a tubular half-man, half-pantomime horse, his back-end a bicycle. At a 1929 Metallic party, the guests were wrapped in foil, the tombola prize was a Kandinsky painting, and the invitation a gorgeous graphic work by Johan Niegemann.

Puppets, and other geometric toys, also formed a fascinating part of the output of the workshops. Schlemmer's haunting, toy-like Michelin Man figures still look oddly radical - his Triadisches Ballet was a very direct inspiration for Philippe Decouflé's mesmeric 1987 video for New Order's 'True Faith'. Paul Klee's son, Felix, was already at the Bauhaus at 14 and his puppet shows sent up the school's largest characters. 'Students and teachers went along to Felix's puppet shows', says Ince, 'to catch up on the latest gossip.'

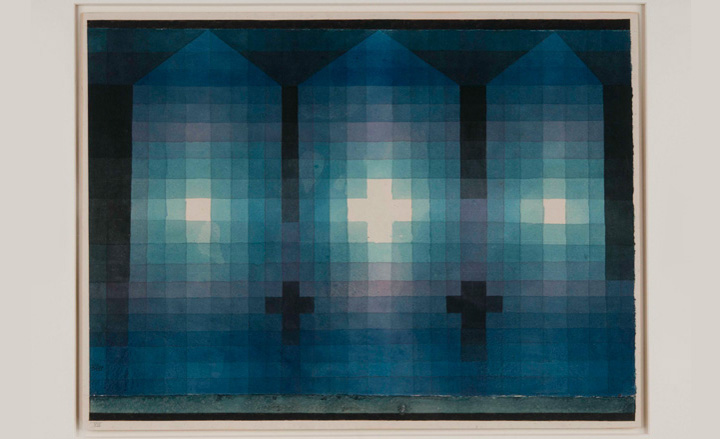

‘Twin Tower’ (1923) by Paul Klee. From a private collection, long term loan to the Franz Marc Museum, Kochel a. See, Germany

There may have been a much-commented-on incipient sexism in ghettoising the Bauhaus ladies into designing and producing textiles and toys but their output was nevertheless extraordinary - and long lasting. Alma Siedhoff-Buscher's 1923 boat-building blocks set is still in production, as is Margaretha Reichardt's string-pull puppet and peg-doll set (all produced by Swiss manufacturer Naef). You do, however, get the impression that these are toys more to please the design-conscious godparents who buy them than the children they are being given to, though at the time their abstract shapes and bold colours must have appeared spectacular.

But the chess set on display at the Barbican (Joseph Hartwig, 1923, also still produced by Naef) is a work of absolute genius, an abstraction of an abstraction which becomes pure, gorgeous sculpture. 'There was an idea of the genius of the child, of the desirability of a return to the pure state of childhood with life and art and play all being one,' explains Ince. The Bauhaus was always struggling financially. The parties slowly became more about fundraising than fun, and the increasingly vehement antagonism of the Nazi regime sealed its fate.

The school will always be remembered for the crystallisation of a moment when design began to be taken seriously. Yet the endless photos of young people dressed up in silly, inventive clothes, fooling around, give a glimpse of the humanity so often seen to be lacking in a modernism characterised by its dedication to a machine aesthetic and a dry vision of endless utopian blocks of worker housing. The Barbican's show helps put the fun back into functionalism.

Entrance to ’Bauhaus: Art as Life’ exhibition, designed by architects Carmody Groarke and graphic designers APFEL, at the Barbican Art Gallery

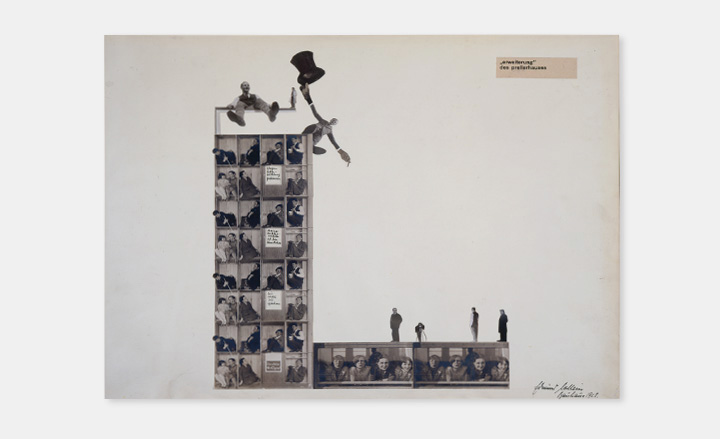

The Barbican’s exhibition puts the fun back in Bauhaus functionalism, by showing some of the personal effects of the school’s alumni, photography of extracurricular activities, and invitations for parties. Pictured is ’Extension to the Prellerhaus’, by Edmund Collein, part of a set of works made for Walter Gropius on his departure from the school, 1928

Invitation to the Beard, Nose and Heart party (1928) by Herbert Bayer. There were four ’official’ parties each year, elaborate affairs with stage designs by Oskar Schlemmer (head of the theatre workshops)

Invitation to the Metallic party (1929) by Johan Niegemann

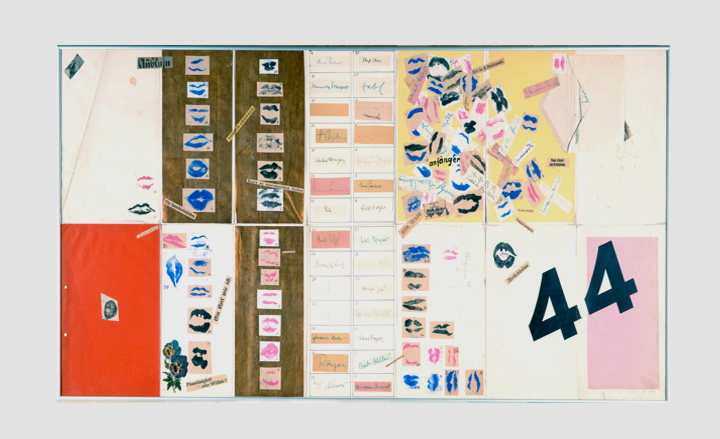

A smoochy collage of kisses given by teachers and students of the Bauhaus to Walter Gropius for his 44th Birthday, 18th May 1927

Installation view featuring, from left: Design for a newspaper stand (1924), Design for a cigarette pavilion (1924) and Poster for exhibition celebrating Kandinsky’s 60th birthday (1926) by Herbet Bayer. Courtesy: Bauhaus-Archiv, Berlin

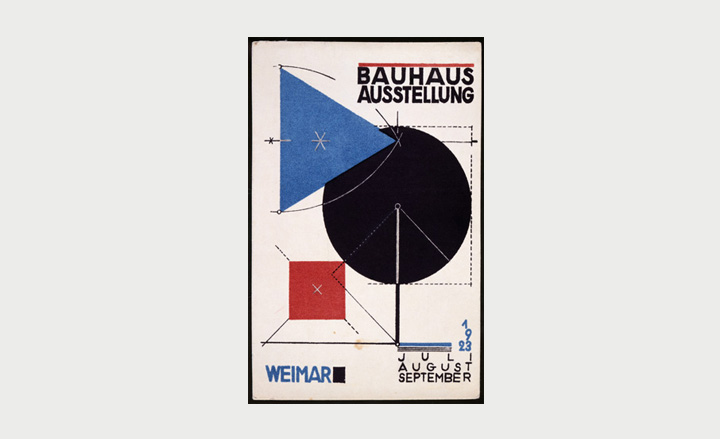

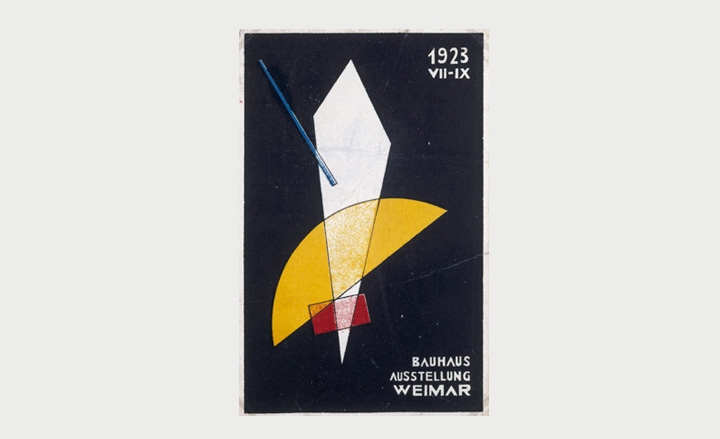

Postcard No 11, by Herbert Bayer, for the summer exhibition in Weimar (1923)

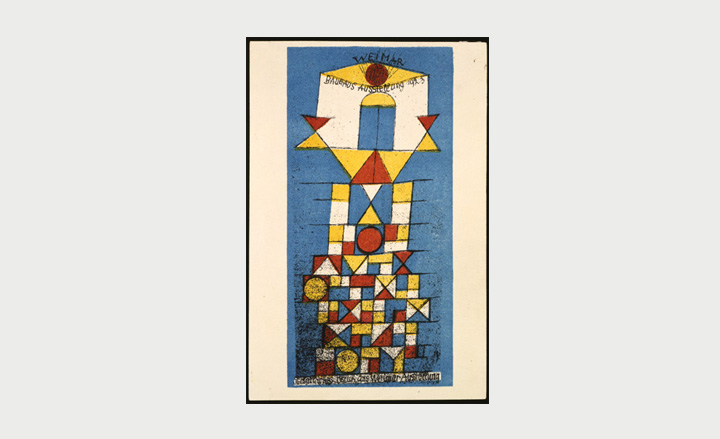

Postcard No 4, by Paul Klee, for the summer exhibition in Weimar (1923)

Postcard No.7, by Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, for the summer exhibition in Weimar (1923)

Masters on the roof of the Bauhaus building (c.1926/1998). From left: Josef Albers, Hinnerk Scheper, Georg Muche, László Moholy-Nagy, Herbert Bayer, Joost Schmidt, Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Lyonel Feininger, Gunta Stölzl and Oskar Schlemmer.

As a whole, the exhibition showcases more than 400 works, including a rich array of painting, sculpture, architecture, film, photography, furniture, graphics, product design, textiles, ceramics and theatre by Bauhaus masters. Pictured is ’Design for a single-family house’ by Farkas Molnar (1922) courtesy: Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

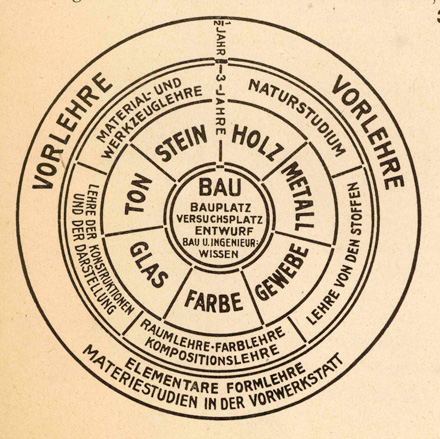

’Graph of the educational curriculum at the Bauhaus’ (1923) by Walter Gropius. Photograph: VG Bild-Kunst, Germany, courtesy Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

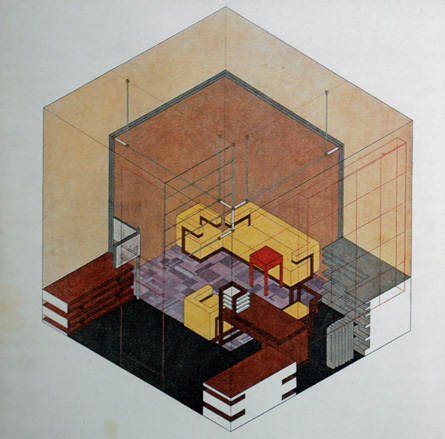

’Isometric drawing of Walter Gropius’s study in the Weimar Bauhaus’ (c.1923) by Herbert Bayer.

’Tomb in Three Parts’ (1923) by Paul Klee. The Louis E. Stern Collection

’Tea Service’ (1924) by Marianne Brandt. Photograph: VG Bild-Kunst, Germany, courtesy: the Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

Coffee machine, warmer, bowl, pot, filter fitting, strainer and lid (1923) by Theodor Bogler. Courtesy: Klassik Stiftung Weimar, Bestand Museen

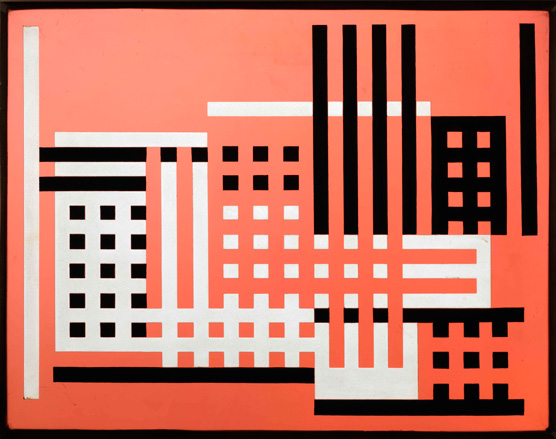

’Factory A’ (1925/26) by Josef Albers. Courtesy: The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/ VG Bild-Kunst, Germany/ Artists Rights Society, New York, USA, 2012

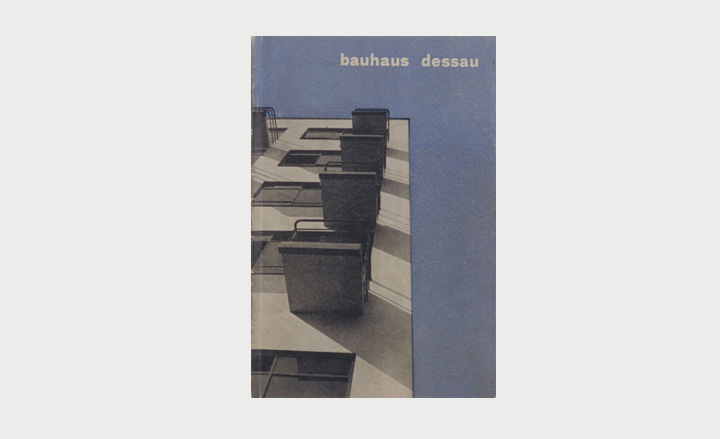

Prospect 'Bauhaus Dessau' (1927) by Herbert and Irene Bayer. courtesy: Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau

'Club Chair from Oeser's home' (1928) by Josef Albers. © VG Bild-Kunst, Germany, courtesy: Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

Installation shot featuring, from left: Lath Chair, TI 1a (1924) and Children’s table, and chairs, TI 3a (1923) by Marcel Breuer.

Installation view featuring from left: set of stacking tables (c.1927) by Josef Albers and nesting tables, B9 (1925–26) by Marcel Breuer. Courtesy: The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation and Klassik Stiftung Weimar, Bestand Museen

Installation view featuring from left: Table and chairs for the Kandinsky house, Dessau (1926), Tubular steel chair (1926) by Club chair (1925–26) by Marcel Breuer. Courtesy:Centre de Création Industrielle (Bequest Nina Kandinsky 1981), Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin and the Victoria and Albert Museuem

Prospectus '14 Bauhausbucher' by Làszlò Moholy-Nagy, 1928. , courtesy: Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

From left: wall hanging (1927) by Gertrud Arndt and wall hanging WE 493/445 (1926) by Anni Albers.

Architectural sculpture (1922) by Otto Werner and Cube Composition (1919) by Johannes Itten.

'The Little Hunchback' for the play 'The Adventures of the Little Hunchback' by Kurt Schmidt and Toni Hergt. The play was performed at the Bauhaus Weimar, 1923.

Installation view featuring, from left: The Triadic Ballet, Wire Figure (1922), The Triadic Ballet, Turc I (1922) and The Triadic Ballet, Turc II (1922) by Oskar Schlemmer.Collection C. Raman Schlemmer

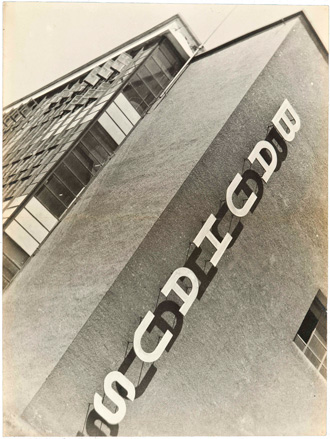

'Bauhaus Building, Dessau' (1930-32)n by Iwao Yamawaki. From Galerie Berinson, Berlin,

'Reflecting Colour-Light-Play/ Reflektorische Farblichtspiele' (1968) by Kurt Schwerdtfeger. The film is a restaging based on his 1922–23 Bauhaus performances.

INFORMATION

‘Bauhaus: Art as Life’ was on view at the Barbican in May 2012. For more information, visit the Barbican website and the Carmody Groarke website

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Edwin Heathcote is the Architecture and Design Critic of The Financial Times. He is the author of about a dozen books including, most recently 'On the Street: In-Between Architecture'. He is the founder of online design writing archive readingdesign.org and the Keeper of Meaning at The Cosmic House.

-

‘I want to bring anxiety to the surface': Shannon Cartier Lucy on her unsettling works

‘I want to bring anxiety to the surface': Shannon Cartier Lucy on her unsettling worksIn an exhibition at Soft Opening, London, Shannon Cartier Lucy revisits childhood memories

-

What one writer learnt in 2025 through exploring the ‘intimate, familiar’ wardrobes of ten friends

What one writer learnt in 2025 through exploring the ‘intimate, familiar’ wardrobes of ten friendsInspired by artist Sophie Calle, Colleen Kelsey’s ‘Wearing It Out’ sees the writer ask ten friends to tell the stories behind their most precious garments – from a wedding dress ordered on a whim to a pair of Prada Mary Janes

-

Year in review: 2025’s top ten cars chosen by transport editor Jonathan Bell

Year in review: 2025’s top ten cars chosen by transport editor Jonathan BellWhat were our chosen conveyances in 2025? These ten cars impressed, either through their look and feel, style, sophistication or all-round practicality

-

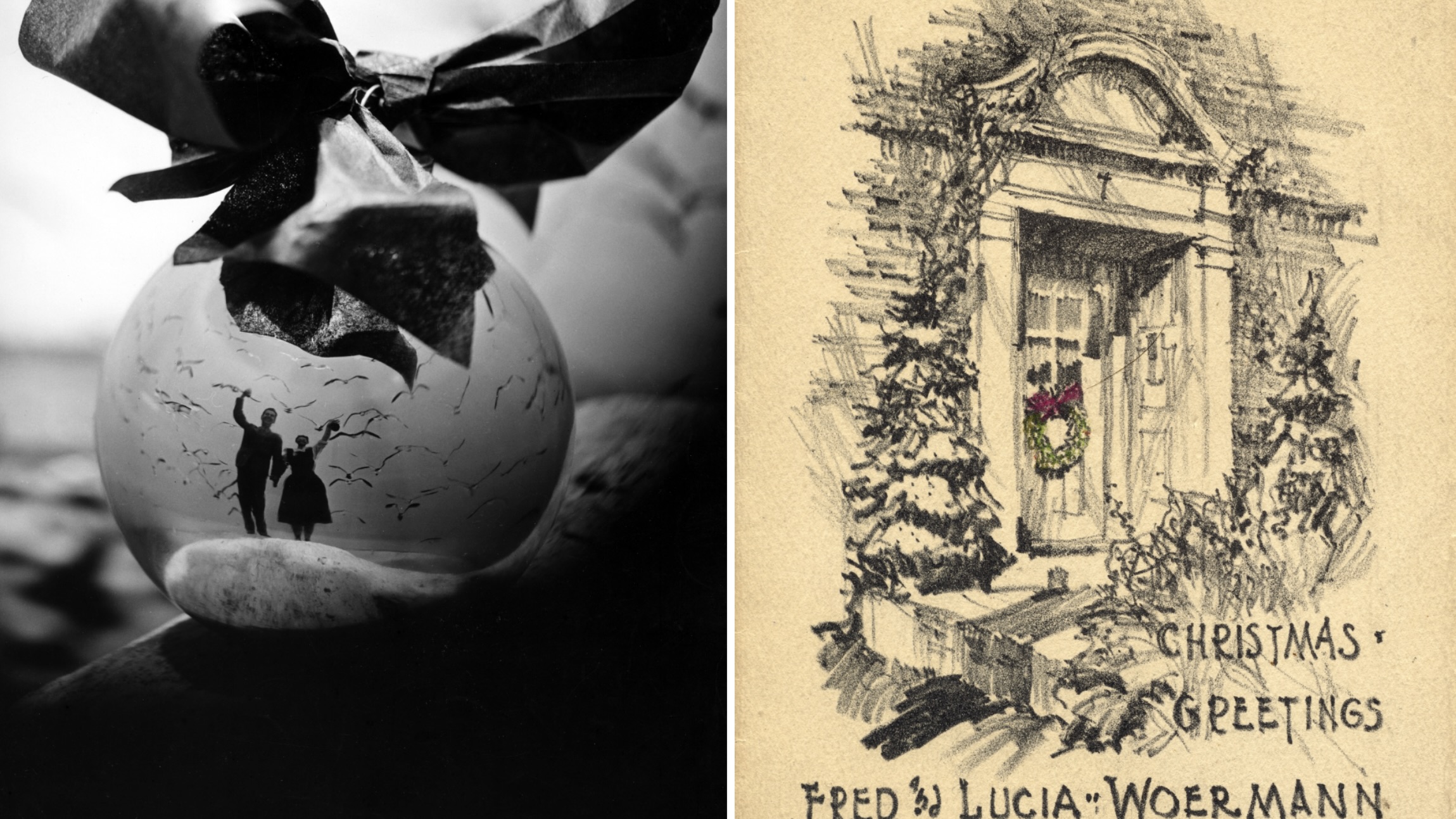

These Christmas cards sent by 20th-century architects tell their own stories

These Christmas cards sent by 20th-century architects tell their own storiesHandcrafted holiday greetings reveal the personal side of architecture and design legends such as Charles and Ray Eames, Frank Lloyd Wright and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

-

The Architecture Edit: Wallpaper’s houses of the month

The Architecture Edit: Wallpaper’s houses of the monthFrom wineries-turned-music studios to fire-resistant holiday homes, these are the properties that have most impressed the Wallpaper* editors this month

-

This modernist home, designed by a disciple of Le Corbusier, is on the market

This modernist home, designed by a disciple of Le Corbusier, is on the marketAndré Wogenscky was a long-time collaborator and chief assistant of Le Corbusier; he built this home, a case study for post-war modernism, in 1957

-

From Bauhaus to outhouse: Walter Gropius’ Massachusetts home seeks a design for a new public toilet

From Bauhaus to outhouse: Walter Gropius’ Massachusetts home seeks a design for a new public toiletFor years, visitors to the Gropius House had to contend with an outdoor porta loo. A new architecture competition is betting the design community is flush with solutions

-

Louis Kahn, the modernist architect and the man behind the myth

Louis Kahn, the modernist architect and the man behind the mythWe chart the life and work of Louis Kahn, one of the 20th century’s most prominent modernists and a revered professional; yet his personal life meant he was also an architectural enigma

-

The Architecture Edit: Wallpaper’s houses of the month

The Architecture Edit: Wallpaper’s houses of the monthFrom Malibu beach pads to cosy cabins blanketed in snow, Wallpaper* has featured some incredible homes this month. We profile our favourites below

-

Doshi Retreat at the Vitra Campus is both a ‘first’ and a ‘last’ for the great Balkrishna Doshi

Doshi Retreat at the Vitra Campus is both a ‘first’ and a ‘last’ for the great Balkrishna DoshiDoshi Retreat opens at the Vitra campus, honouring the Indian modernist’s enduring legacy and joining the Swiss design company’s existing, fascinating collection of pavilions, displays and gardens

-

Three lesser-known Danish modernist houses track the country’s 20th-century architecture

Three lesser-known Danish modernist houses track the country’s 20th-century architectureWe visit three Danish modernist houses with writer, curator and architecture historian Adam Štěch, a delve into lower-profile examples of the country’s rich 20th-century legacy