Cultural exchange: MoMA goes big in Paris at Fondation Louis Vuitton

‘Being Modern: MoMA in Paris’ is an extraordinary exhibition to the extent that some 200 works have been transplanted from the Museum of Modern Art to the Fondation Louis Vuitton while the New York institution undergoes an expansion by Diller Scofidio + Renfro. Masterpieces including Hope II (1908), by Klimt; The Studio (1928) by Picasso; de Kooning’s Women I (1952); Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel (1913); and Rothko’s No 10 (1950) arrived to Frank Gehry’s permanently anchored ark in dozens of shipments in accordance with restrictions such as how much value could be loaded onto a plane. The MoMA’s variation of Constantin Brâncuși’s Bird in Space (1923) has landed in Paris for the first time, as has Andy Warhol’s painted Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962).

But this exhibition is also extraordinary for its presentation, which strongly demonstrates what makes the MoMA so unique. Nearly 90 years old, the museum boasts a world-renowned collection of European works – largely accumulated under the aegis of its founding members, its first director Alfred H Barr Jr, and a steady stream of wealthy donors in addition to a diverse inventory of American art that reflects the zeitgeist over time.

L’Atelier, 1927-1928, by Pablo Picasso; and Oiseau dans l’espace, 1928, by Constantin Brâncuși. © Succession Brâncuși (ADAGP) 2017. © Succession Picasso 2017.

While the visit may seem chronological, it doesn’t take long to realise that the coexistence of different disciplines makes for an experience that is far more nuanced and unexpected, which is therefore sure to surprise the typical Parisian museumgoer (and by extension, the throngs of tourists). Even those who could map out the MoMA by heart will find themselves freshly engaged.

MoMA director Glenn D Lowry describes the approach – overseen by MoMA chief curator of photography Quentin Bajac – as ‘a chance to scramble what we normally do’. Indeed, visitors entering the exhibition are immediately greeted by Brâncuși’s bird and The Bather (c1885) by Cézanne – one of the museum’s top treasures – but then discover a series by Walker Evans to one side, and objects from the 1934 ‘Machine Art’ show (a self-aligning ball bearing and a flush valve) to the other.

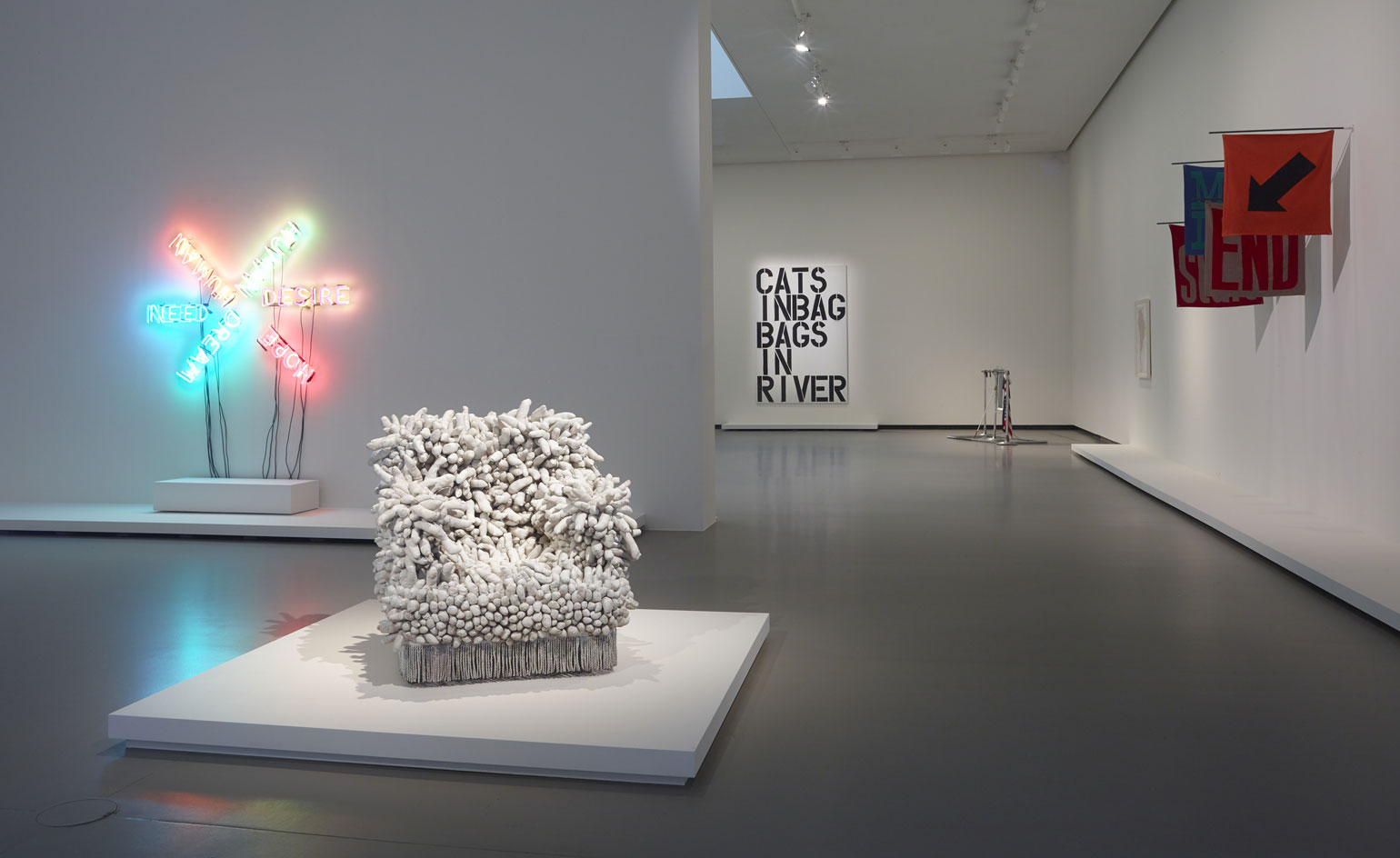

Installation view of ‘Being Modern: MoMA in Paris’ at Foundation Louis Vuitton.

‘That first room is like a microcosm of the museum,’ Lowry said, referring also to Hopper’s House by the Railroad (1925), one of the earliest additions to the permanent collection. As another example, Steamboat Willie, the iconic animated Walt Disney film featuring Mickey Mouse, plays on an adjacent wall to Magritte’s The False Mirror (1929) with its eye consumed by a cloud-filled sky. On the main floor, a cluster of works includes Ellsworth Kelly, a fragment of old curtain wall from the United Nations, Carl Andre’s lead tiles, and a maquette of Lever House; altogether, they add up to a remarkably fluid practice of minimalism. Romare Bearden’s Patchwork Quilt (1970) and Kerry James Marshall’s Untitled (Club Scene) (2013) weave a distinctly African-American experience into the fabric of the show, just as the Rainbow Flag, conceived by Gilbert Baker in 1978, sends a strong message about the MoMA’s mandate of inclusiveness – people, yes, but also how it defines art.

Up near the terrace, a wall in one of the corridors boasts a trifecta of contemporary symbols: the @, the familiar red Google Maps pin, and The Power Symbol, which have become so ubiquitous in our daily lives that we rarely pause to consider their efficient, universal design. Arguably the most idiosyncratic juxtaposition consists of Shigetaka Kurita’s original emoji characters for NTT DOCOMO devices alongside a complete reconstruction of Lele Saveri’s The Newstand – transit system subway tiles, et al – plus Rirkrit Tiravanija’s newspaper collage that reads ‘The Days of this Society is Number,’ which draws from leftist French philosopher Guy Debord. Saveri, who flew from New York to acquaint museum assistants with the zines in his pop-up concession, summed up the context best: ‘It’s very strange; it’s not really explainable... I never expected the MoMA to eventually have it in their collection.’

Tokyo emoji, 1998, by Shigetaka Kurita, for NTT DOCOMO

For every gallery that overstimulates – Joseph Beuys near Yayoi Kusama near Bruce Nauman near Robert Smithson (incidentally, his drawing is called The Museum of the Void) – there are smaller galleries filled with a single work, such as Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills (1970-88), and this is where the show responds directly to the Fondation’s architecture. ‘Each of those rooms becomes a mini-chapel, and those become the counterpoints,’ Lowry pointed out. The Forty Part Motet, an audio installation by Janet Cardiff that produces an ethereal choir from as many individual, boxy black speakers, quite literally assumes this role; to some visitors, it might prove more transcendent than any of the highly-anticipated paintings.

But since many of those paintings have ties to Paris, and ended up in New York because so many patrons were following the waves of modern art emerging out of both cities, the exhibition feels, at various points, like a mirror being held up from the other side of the Atlantic. Or as Lowry noted, ‘We thought there was a symmetry to that gesture – the idea of a museum grows out of so many ideas here, and in Paris in particular during the 1920s. Ninety years later, one could flip it over and say, “Look what you’ve created, look what you’ve helped bring into being.”’

Installation view of ‘Being Modern: MoMA in Paris’ at Foundation Louis Vuitton.

Human/Need/Desire, 1983, by Bruce Nauman. Gifted by Emily and Jerry Spiegel, 1991

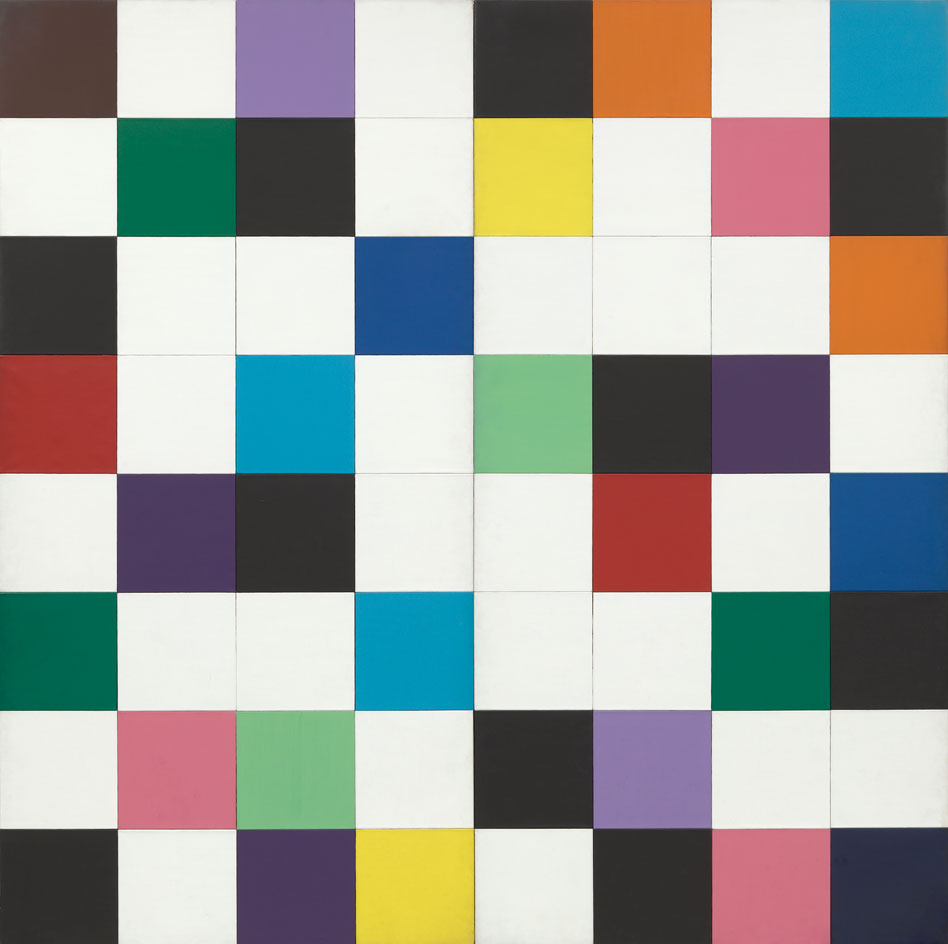

Brushstrokes Cut into Forty-Nine Squares and Arranged by Chance, 1951, by Ellsworth Kelly.

Installation view of ‘Being Modern: MoMA in Paris’ at Foundation Louis Vuitton.

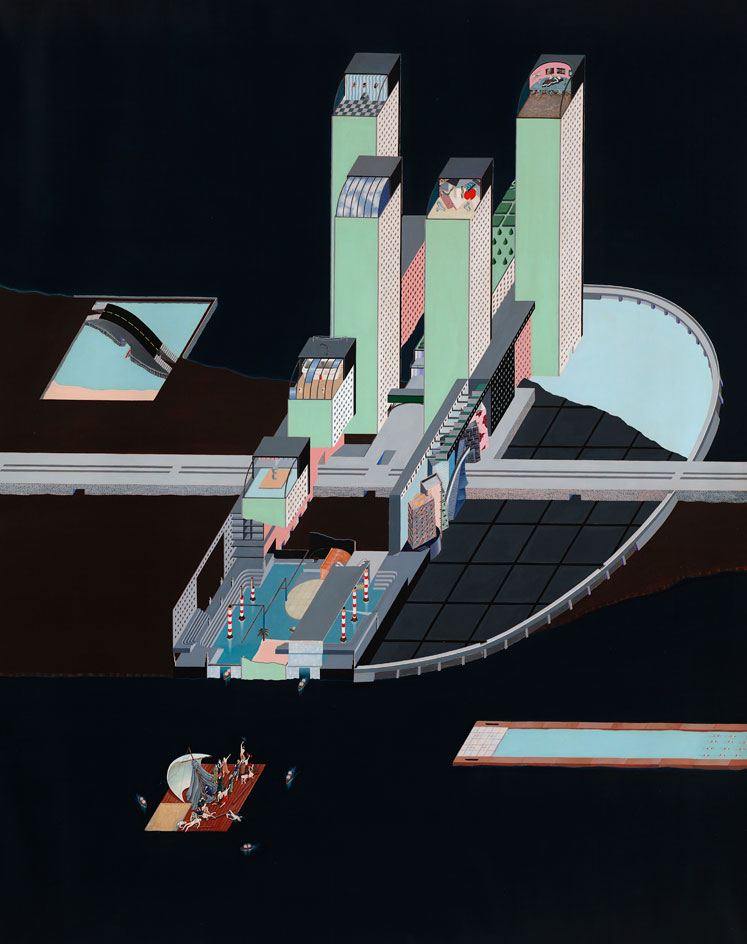

Welfare Palace Hotel Project, Roosevelt Island, New York, New York (Cutaway axonometric), 1976, by Rem Koolhaas, Madelon Vriesendorp.

Untitled Film Still, 1978, by Cindy Sherman

Installation view of ‘Being Modern: MoMA in Paris’ at Foundation Louis Vuitton.

Installation view of ‘Being Modern: MoMA in Paris’ at Foundation Louis Vuitton.

Installation view of ‘Being Modern: MoMA in Paris’ at Foundation Louis Vuitton.

INFORMATION

‘Being Modern: MoMA in Paris’ is on view until 5 March 2018. For more information, visit the Fondation Louis Vuitton website

ADDRESS

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Fondation Louis Vuitton

8 Avenue Mahatma Ghandi

75116 Paris

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss

-

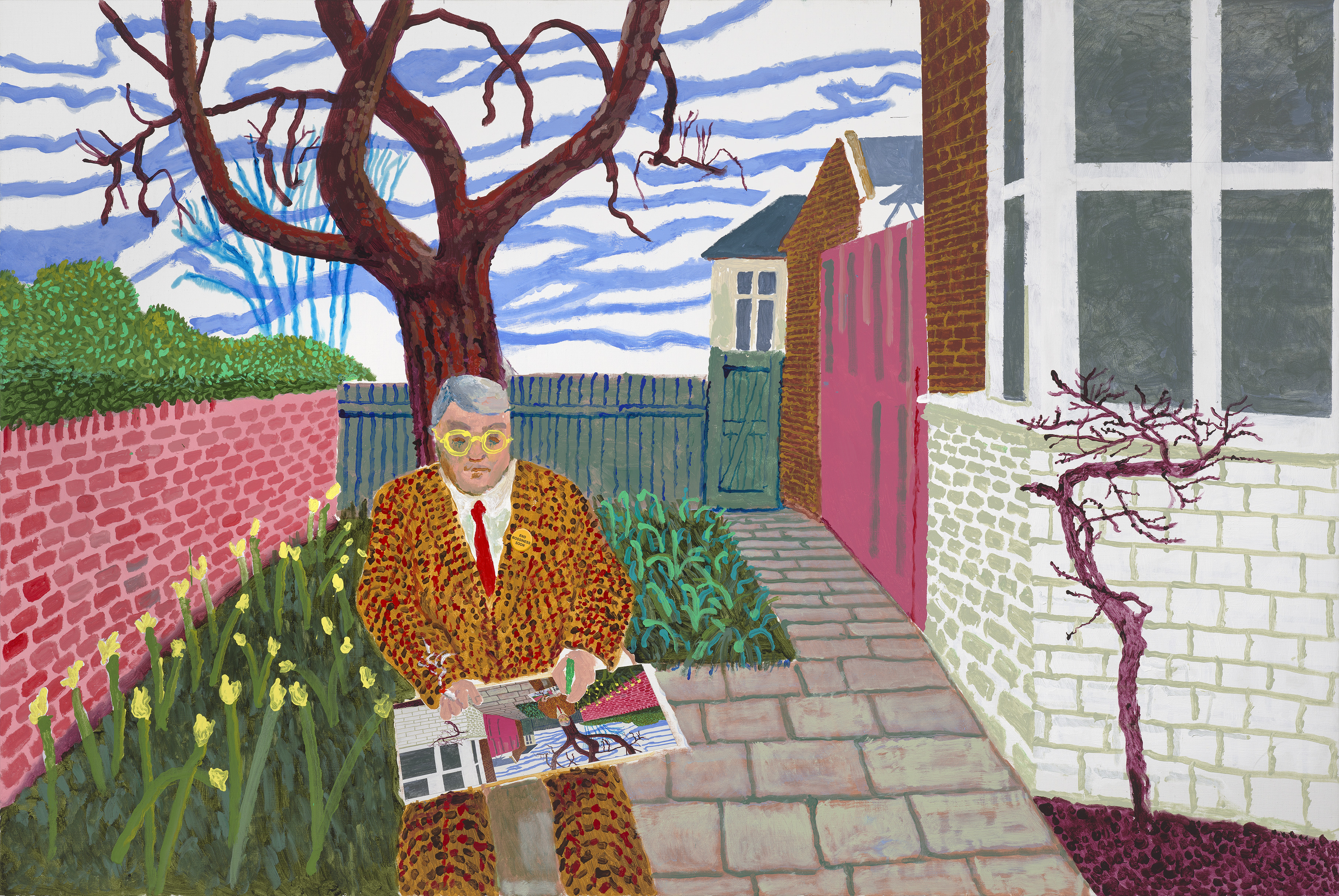

‘David Hockney 25’: inside the artist’s blockbuster Paris show

‘David Hockney 25’: inside the artist’s blockbuster Paris show‘David Hockney 25’ has opened at Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris. Wallpaper’s Hannah Silver took a tour of the colossal, colourful show

By Hannah Silver

-

MoMA names Christophe Cherix its new director

MoMA names Christophe Cherix its new directorThe Swiss-born curator has worked in the Museum of Modern Art’s drawings and prints department since 2007

By Anna Fixsen

-

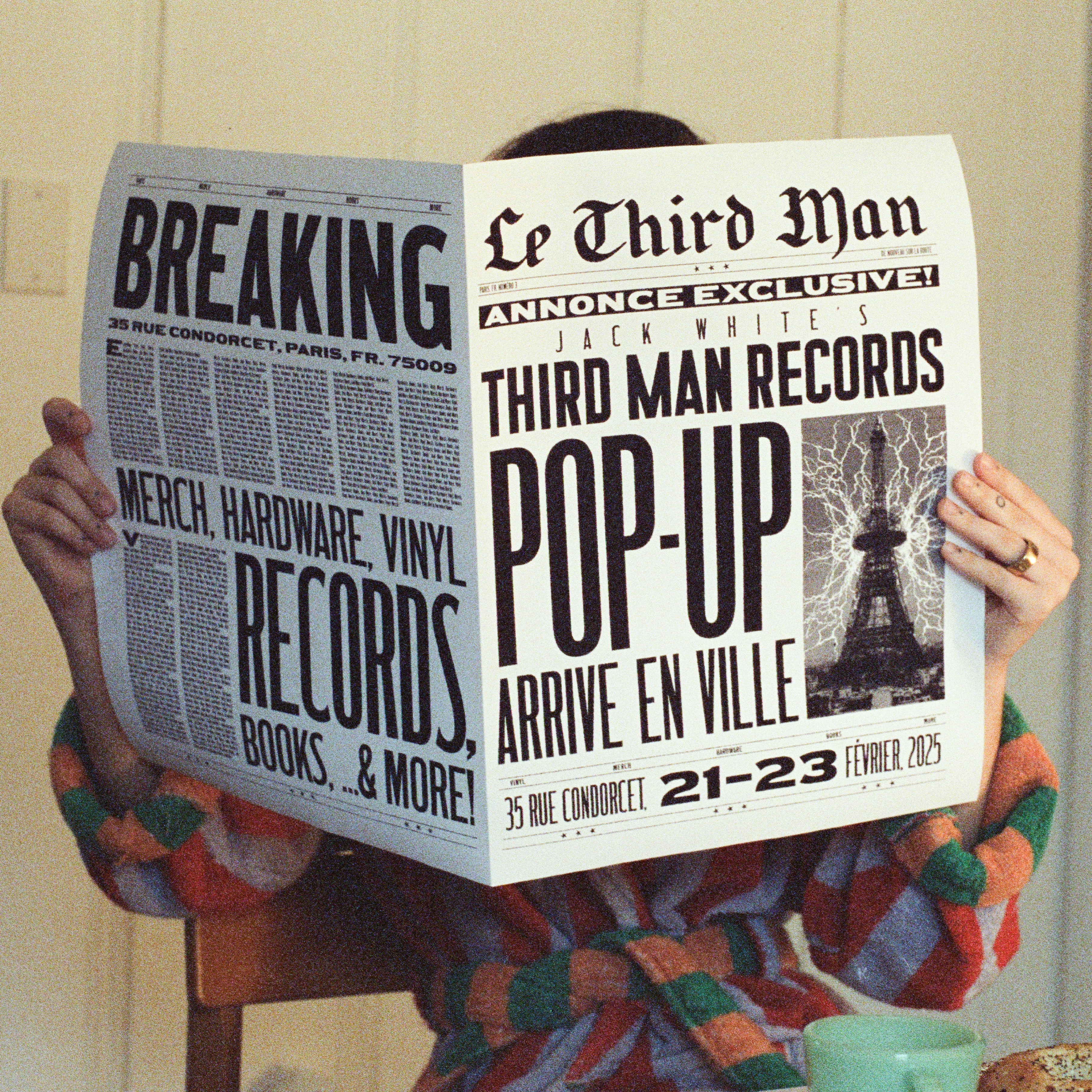

Jack White's Third Man Records opens a Paris pop-up

Jack White's Third Man Records opens a Paris pop-upJack White's immaculately-branded record store will set up shop in the 9th arrondissement this weekend

By Charlotte Gunn

-

‘The Black woman endures a gravity unlike any other’: Pharrell Williams explores diverse interpretations of femininity in Paris

‘The Black woman endures a gravity unlike any other’: Pharrell Williams explores diverse interpretations of femininity in ParisPharrell Williams returns to Perrotin gallery in Paris with a new group show which serves as an homage to Black women

By Amy Serafin

-

What makes fashion and art such good bedfellows?

What makes fashion and art such good bedfellows?There has always been a symbiosis between fashion and the art world. Here, we look at what makes the relationship such a successful one

By Amah-Rose Abrams

-

Architecture, sculpture and materials: female Lithuanian artists are celebrated in Nîmes

Architecture, sculpture and materials: female Lithuanian artists are celebrated in NîmesThe Carré d'Art in Nîmes, France, spotlights the work of Aleksandra Kasuba and Marija Olšauskaitė, as part of a nationwide celebration of Lithuanian culture

By Will Jennings

-

Out of office: what the Wallpaper* editors have been doing this week

Out of office: what the Wallpaper* editors have been doing this weekInvesting in quality knitwear, scouting a very special pair of earrings and dining with strangers are just some of the things keeping the Wallpaper* team occupied this week

By Bill Prince

-

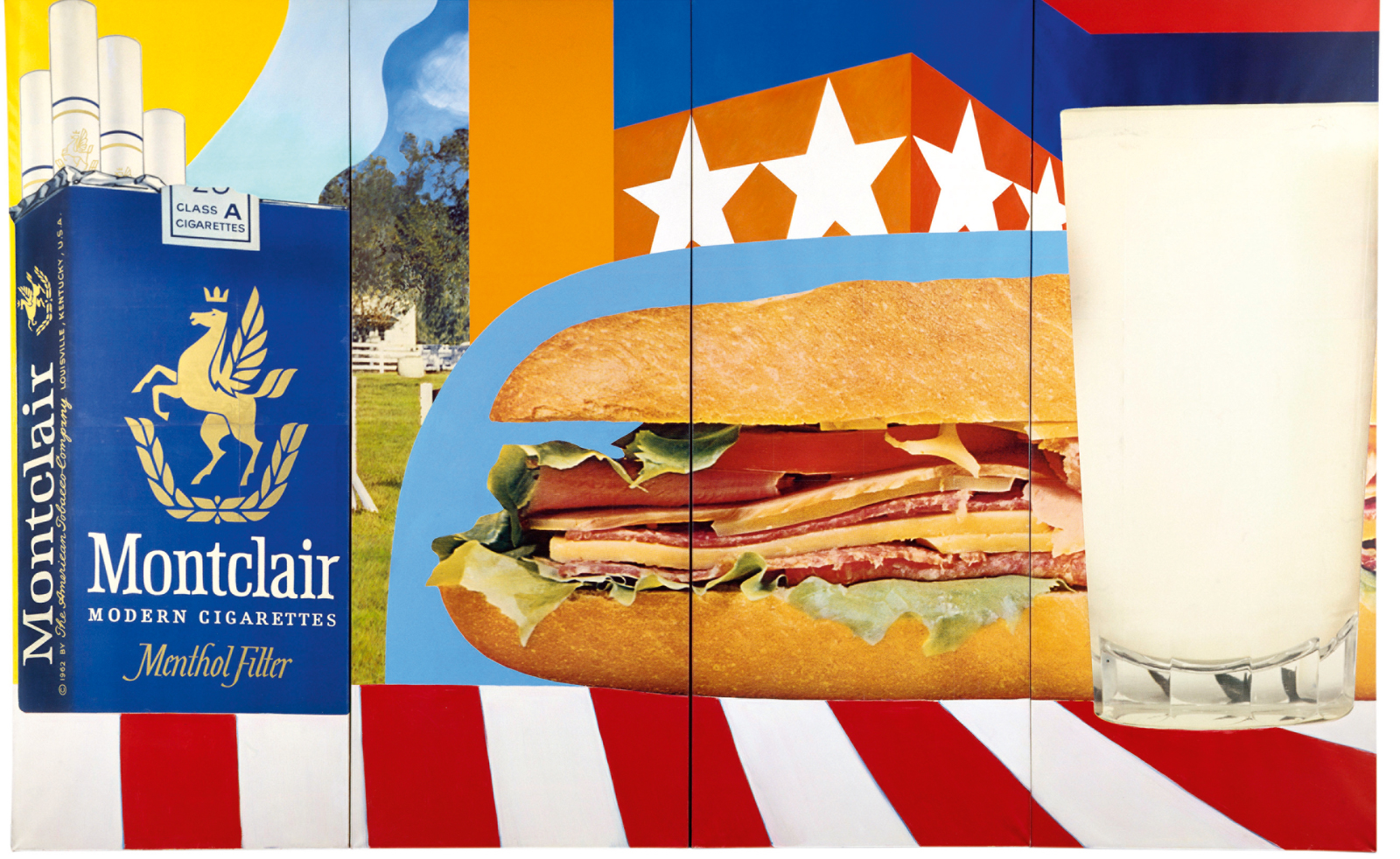

Tom Wesselmann’s enduring influence on pop art goes under the spotlight in Paris

Tom Wesselmann’s enduring influence on pop art goes under the spotlight in Paris‘Pop Forever, Tom Wesselmann &...’ is on view at Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris until 24 February 2025

By Ann Binlot