Night vision: Tracey Emin and Joseph Kosuth light up Blackpool's Grundy Art Gallery

'Neon: The Charged Line', opens this weekend at Grundy Art Gallery in Blackpool – and is well worth a trip up north.

Blackpool, with its circling gulls, forgotten chippies and dangerously cheap beer, is not the first place you'd expect to find a Joseph Kosuth masterpiece nestled next to an iconic Tracey Emin. This juxtaposition of the great and the gaudy is precisely the joy of 'Neon: The Charged Line', which opens this weekend at Grundy Art Gallery.

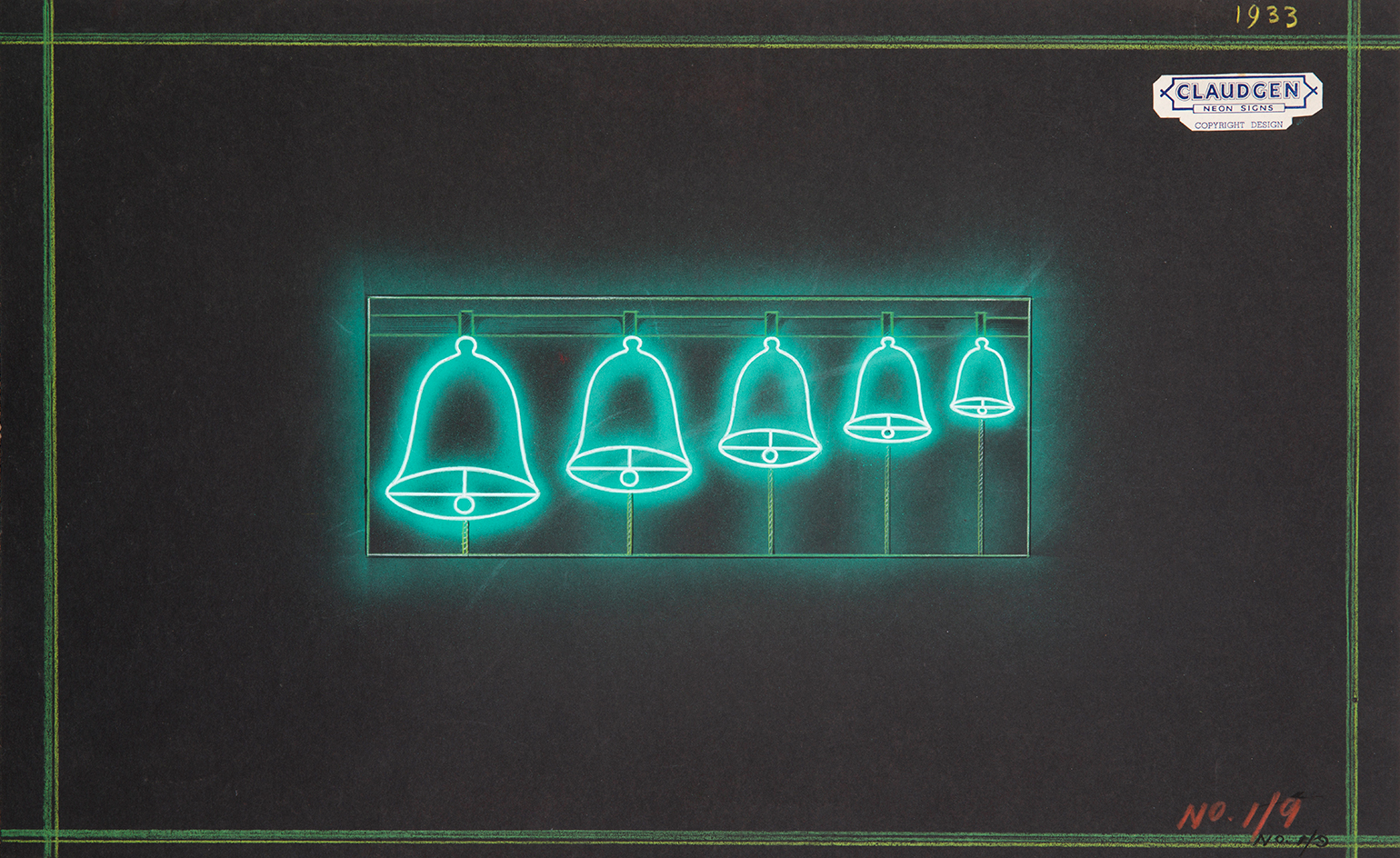

Coinciding with the Blackpool Illuminations, the exhibition charts the use of neon in fine art since the 1960s, while a parallel exhibition in the upstairs gallery shines a light on lost neon sign designs of the 1930s. Of these anonymous sketches, it's unclear how many made it to production. Either way, the surviving drawings, unique to Blackpool, are works of art in themselves. They capture neon's hazy glow with finely smudged chalk on night-black paper, providing a rare glimpse into the medium's origin.

Downstairs, an eerie green light from the contemporary works snaps visitors into the present. 'Neon is at once futurisitc and inherently retro,' curator Richard Parry says of the lightform's timeless quality. 'And there's something sci-fi about Blackpool that neon just works with.'

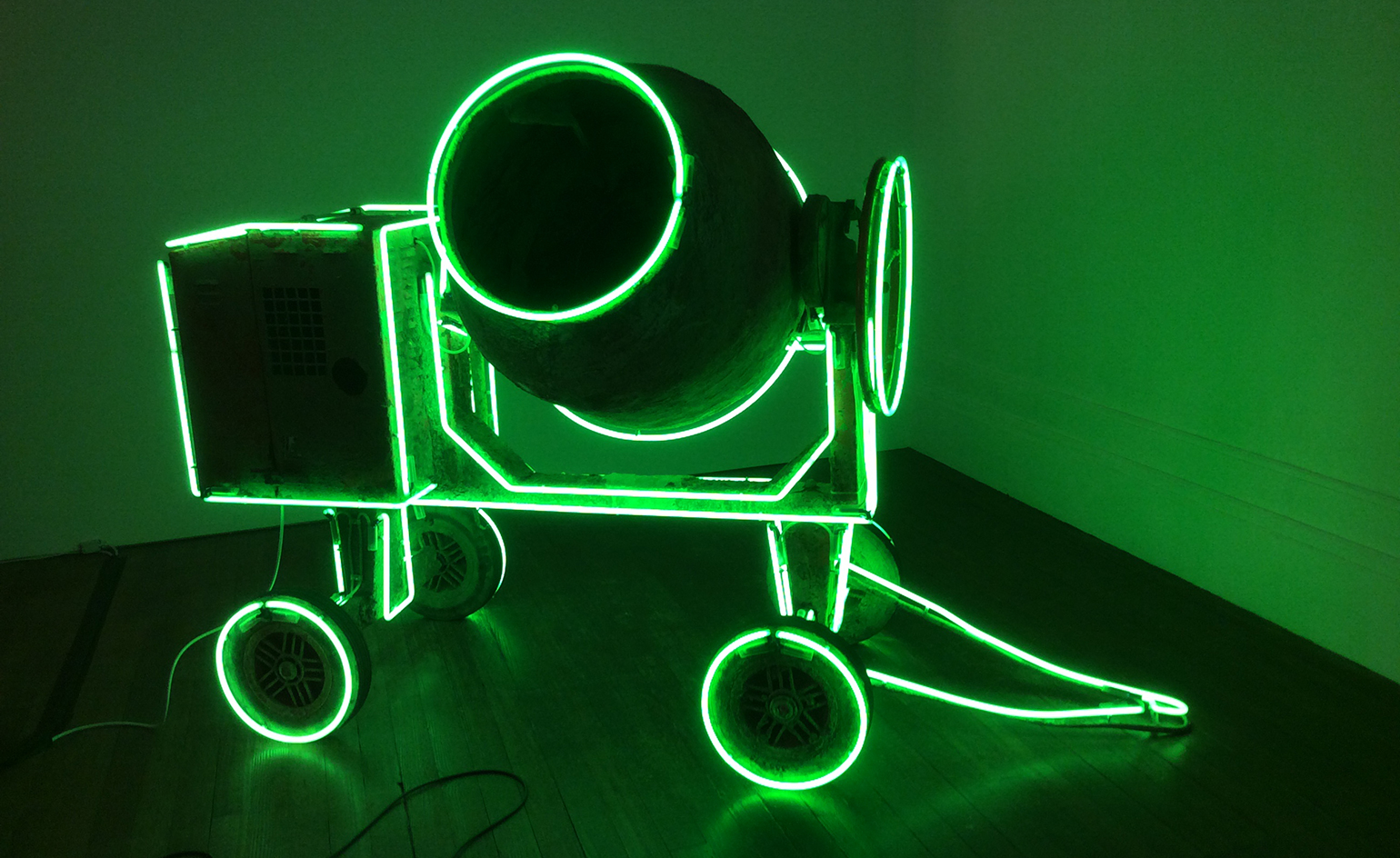

This 'Blackpool-style' of chirpy, seaside neons come courtesy of Evran Tekinoktay's psychedelic TWIZ (2015) and BAMBI (2014), in the largest room of the gallery – two of a handful of dazzling kinetic pieces included. Opposite, an enormous graphic work from David Batchelor requires some serious sunglasses, and casts a lurid green hue across the space. Painted glass tubes are delicately wrapped around a reclaimed cement mixer 'which reflects Blackpool's working class history', the curator explains.

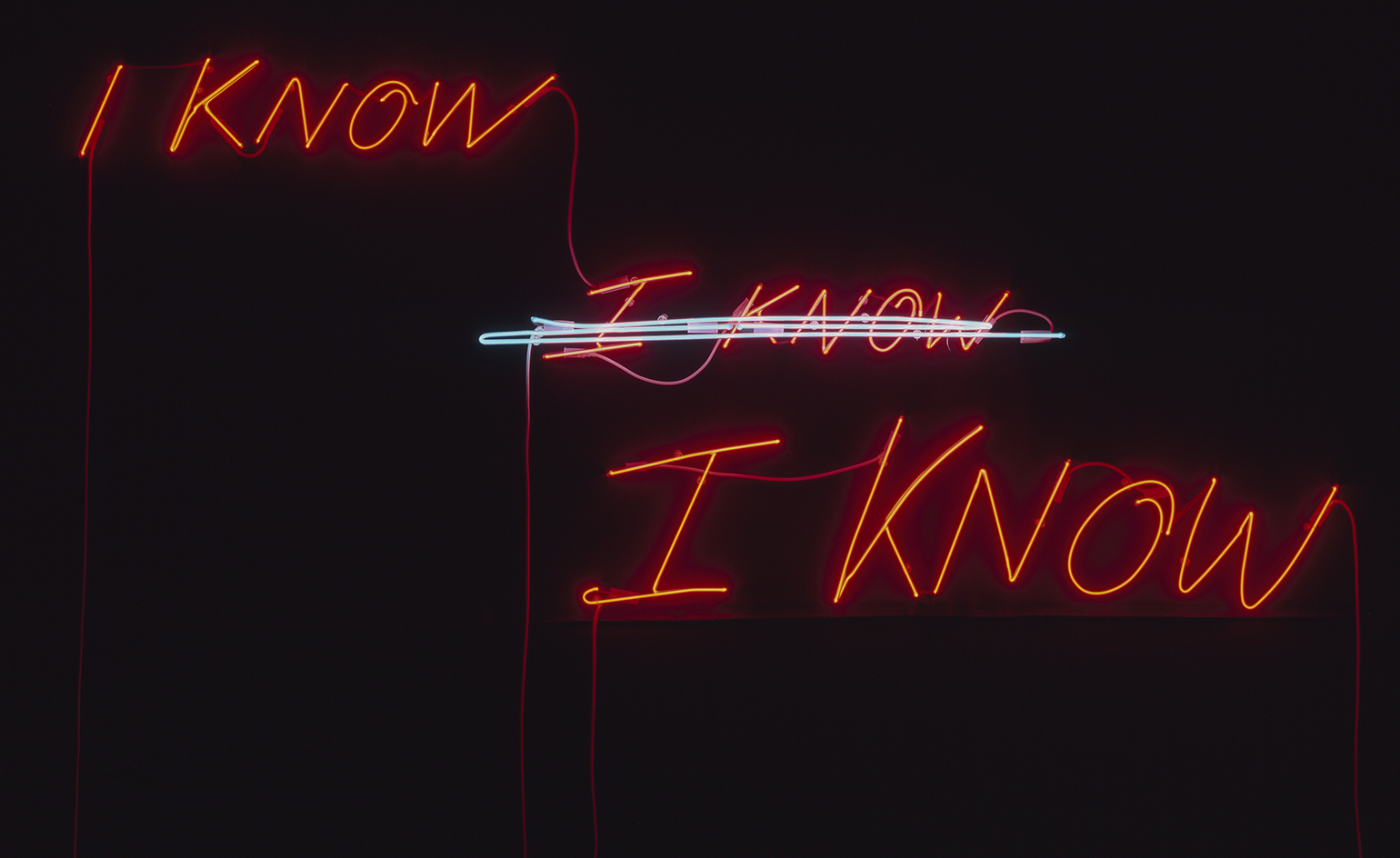

Neon's darker side (if it has one) is seen in the 'Text/Language' room, which delves into neon's relationship with the written word. Here, Tracey Emin's I know I know I know pulstates in her classic, impassioned scrawl, while an entire, Kosuth-grey wall is filled with his bold, meta-sentiments that explore the relationship between word, sign and meaning.

These pieces – particularly Kosuth's seminal work Neon (1965) – probe the artistic qualities of the medium. It is a lightform created to illuminate only itself – light for light's sake. This makes it an ideal material for conceptual artists like Kosuth – but a tricky thing to curate. Parry has managed beautifully by turning all of the overhead gallery lights off, building partition walls and covering all the windows. This way, different colour neons mingle in the middle, and darkened corners are left as rare, contrasting moments of calm. In these, we pause to reconsider the Blackpool Illuminations, questioning whether they have a place in art history books as well as tourist brochures.

Coinciding with the Blackpool Illuminations, the exhibition charts the use of neon in fine art since the 1960s, while a parallel exhibition in the upstairs gallery shines a light on lost neon sign designs of the 1930. Pictured: I Know I Know I Know, 2002. Courtesy the artist and White Cube

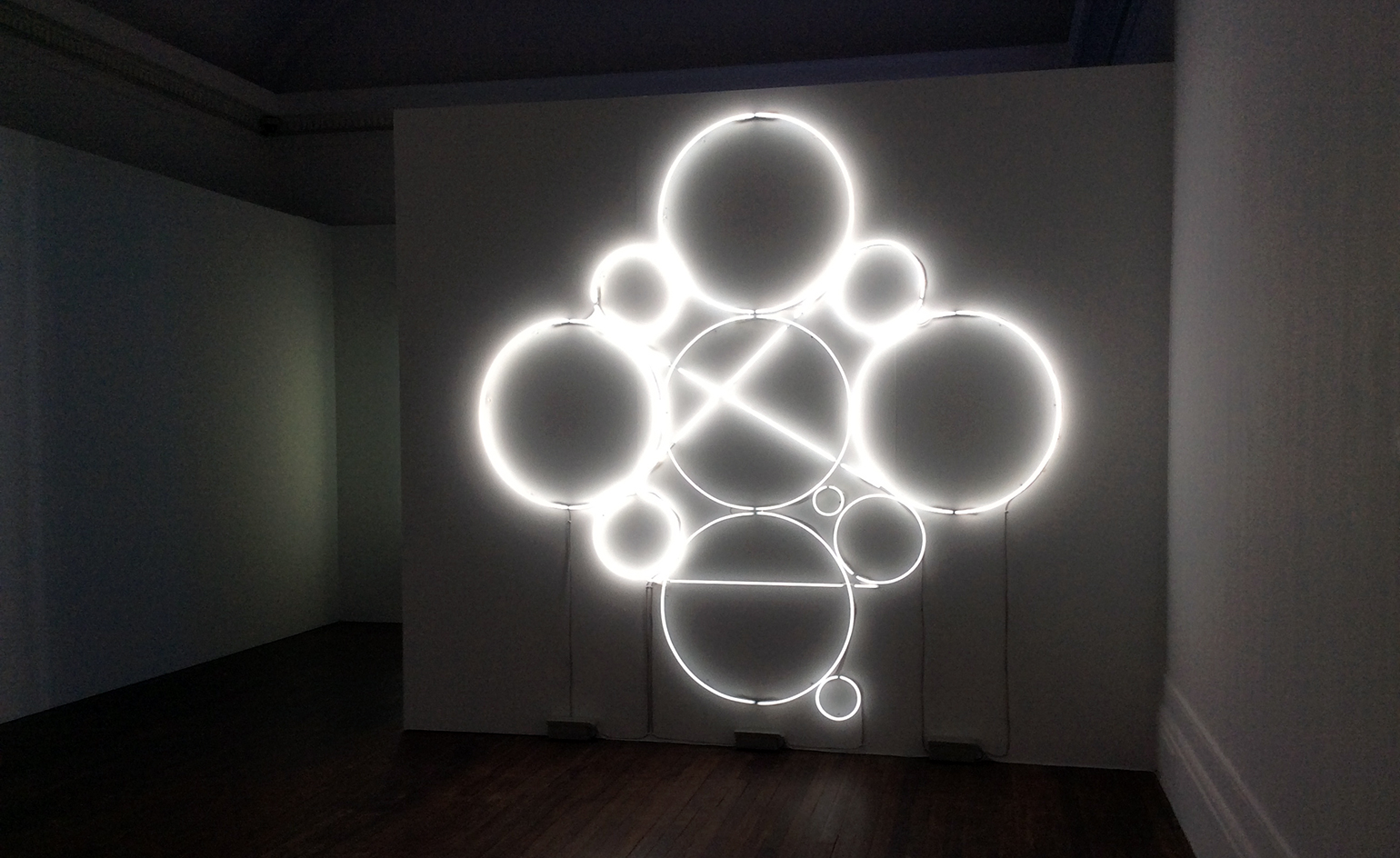

Pictured: Neon, 1965. Courtesy the artist and Sprueth Magers London

'Neon is at once futuristic and inherently retro,' curator Richard Parry says of the lightform's timeless quality.

Courtesy the artist and Simon Lee Gallery London / Hong Kong

Half sculpture, half painting, the selection of works force us to question whether the Blackpool Illuminations have a place in art history as well as the tourist books. Pictured: 2012, by Mai-Thu Perret, 2008.

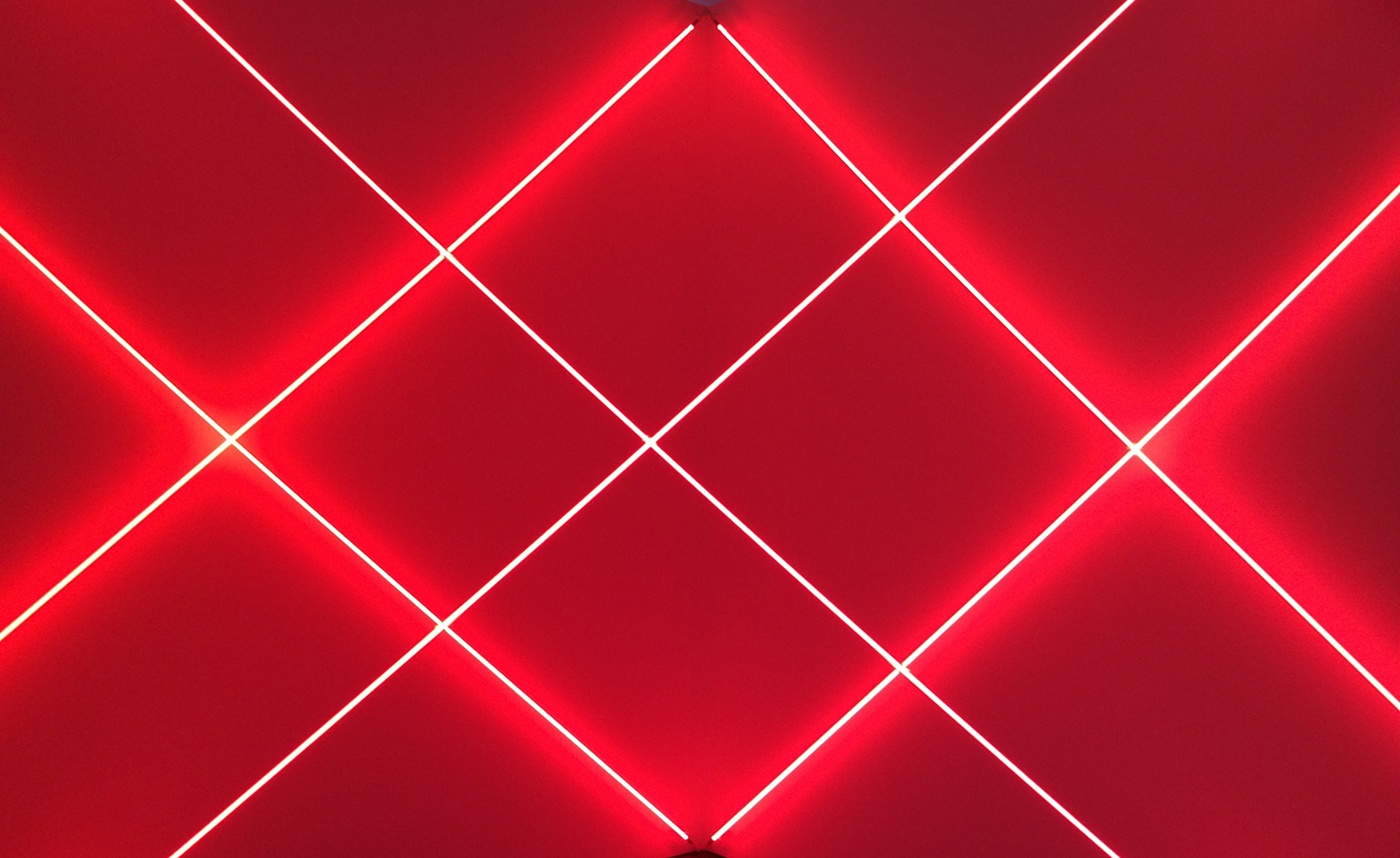

Pictured: Triple X Neonly, by François Morellet, 2012. Courtesy Collection Cattelain

Pictured left: Apocalypse Ballet (neon-belt), by Mai-Thu Perret, 2006. Courtesy the Bonnefantenmuseum, Masstricht. Right: BUMP, by Prem Sahib, 2013.

Blackpool, with its circling gulls, forgotten chippies and cheap beer, is not the first place you'd expect to find a Joseph Kosuth masterpiece nestled next to an iconic Tracey Emin. This juxtaposition of the great and the gaudy is precisely the joy of 'Neon: The Charged Line'. Pictured: installation view.

Of the early sketches, it's unclear how many made it to production. Either way, the surviving drawings, unique to Blackpool, are artworks in themselves, capturing neon's hazy glow with finely smudged chalk. Pictured: Untitled sketch from the 1930s

Untitled sketch from the 1930s

INFORMATION

’Neon: The Charged Line’ is on view until 7 January 2017. For more information, visit the Grundy Art Gallery website

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

ADDRESS

Grundy Art Gallery

Queen Street

Blackpool, FY1 1PU

Elly Parsons is the Digital Editor of Wallpaper*, where she oversees Wallpaper.com and its social platforms. She has been with the brand since 2015 in various roles, spending time as digital writer – specialising in art, technology and contemporary culture – and as deputy digital editor. She was shortlisted for a PPA Award in 2017, has written extensively for many publications, and has contributed to three books. She is a guest lecturer in digital journalism at Goldsmiths University, London, where she also holds a masters degree in creative writing. Now, her main areas of expertise include content strategy, audience engagement, and social media.

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss

-

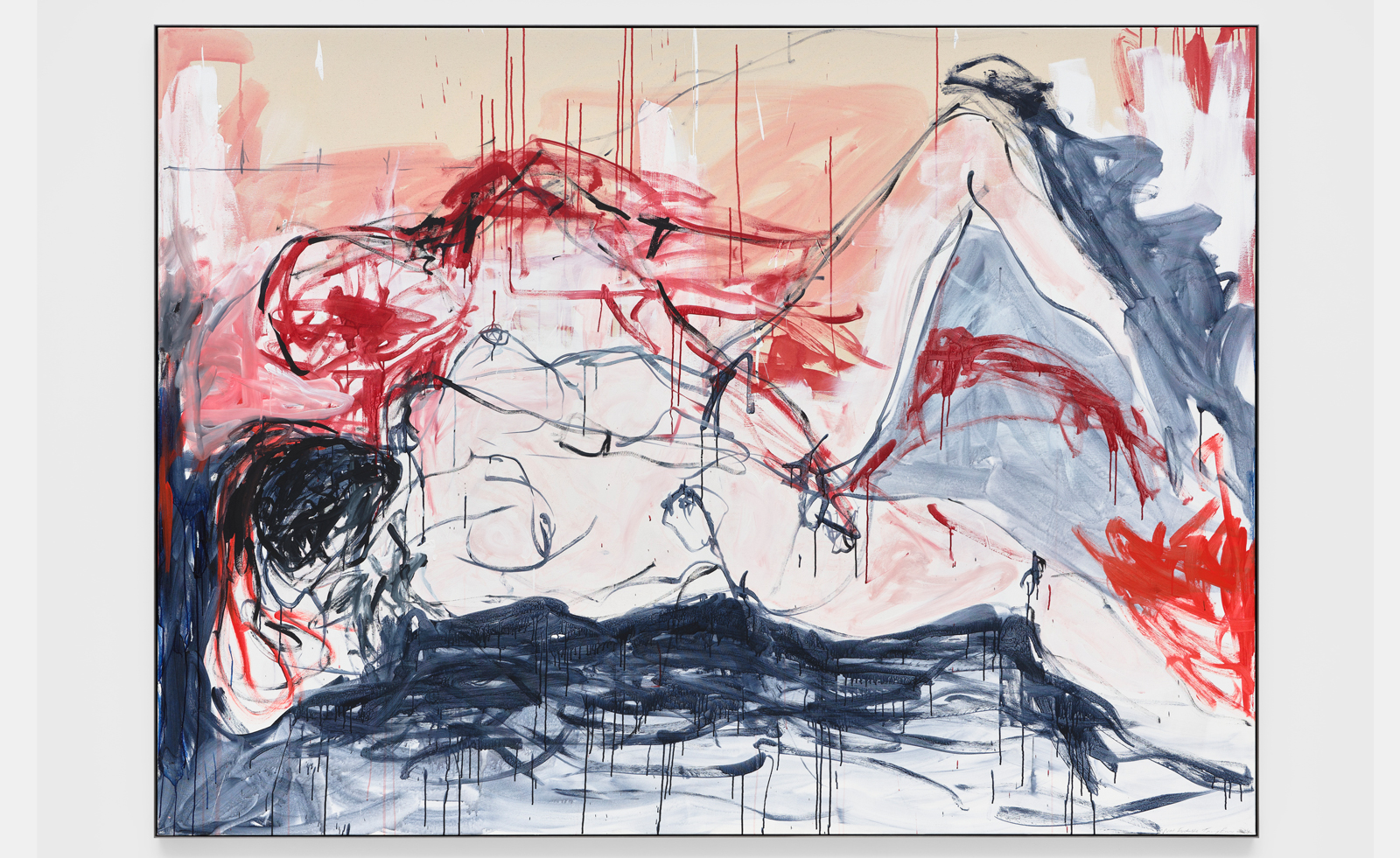

‘This blood that is flowing is my blood, and that should be a positive thing’: Tracey Emin at White Cube

‘This blood that is flowing is my blood, and that should be a positive thing’: Tracey Emin at White CubeTracey Emin’s exhibition ‘I followed you to the end’ has opened at White Cube Bermondsey in London, and traces the artist’s journey through loss

By Hannah Silver

-

Studio Lenca nods to Salvadorian heritage with riot of colour in Margate

Studio Lenca nods to Salvadorian heritage with riot of colour in MargateStudio Lenca considers boundaries in ‘Leave to Remain’ at Carl Freedman Gallery in Margate

By Emily Steer

-

Politics, protest and potential: the Barbican explores the power of textiles in art

Politics, protest and potential: the Barbican explores the power of textiles in artUnravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art’ at the Barbican Centre in London explores how far the medium has evolved in the last sixty years

By Emily Steer

-

At Melbourne’s NGV Triennial 2023, artists consider magic, matter and memory

At Melbourne’s NGV Triennial 2023, artists consider magic, matter and memoryMelbourne’s NGV has opened its third triennial, uniting art, design and architecture from around the world

By Elias Redstone

-

The Weight of Things: Damien Hirst curates his retrospective in Munich

The Weight of Things: Damien Hirst curates his retrospective in MunichThe Weight of Things, at The Museum of Urban and Contemporary Art, Munich (MUCA), was curated by Hirst himself and comprises work spanning four decades

By Amah-Rose Abrams

-

Frieze London 2023: what to see and do

Frieze London 2023: what to see and doEverything you want to see at Frieze London 2023 and around the city in our frequently updated guide

By Hannah Silver

-

Tracey Emin interview: ‘If I hadn’t made art, I would be dead by now’

Tracey Emin interview: ‘If I hadn’t made art, I would be dead by now’We speak to British artist Tracey Emin in her hometown of Margate, where she has created a new painting to raise funds for TKE Studios, a pioneering complex serving the next generation of radical creatives. ‘I don’t want to die being an artist that made really interesting work. I want to make a future.’

By Sheila Lam

-

A woman’s right to pleasure: the LA exhibition rewriting the history of female sexuality

A woman’s right to pleasure: the LA exhibition rewriting the history of female sexualityArtists including Nan Goldin, Tracey Emin and Reka Nyari take part in ‘BlackBook Presents: A Woman’s Right to Pleasure’ at Sotheby’s LA

By Hannah Silver