Sculpture’s rising star Camille Blatrix on process, pathos and YouTube learning

Ahead of his solo show at Kunsthalle Basel, the Paris-based artist talks us through his mysterious ‘objects’

Camille Blatrix’s studio in the 14th arrondissement of Paris is cluttered with carpentry tools and random bits of decoration: dollar signs graffitied on the wall;

a clay minotaur; ten years’ worth of empty beer bottles; and a painting by his father, who used to be an artist, too. The 35 sq m studio, which Blatrix called home until 2017 (when he met his wife), is in a semi-dilapidated building of artists’ ateliers rented out by the mayor’s office. He keeps it because it is cheap and charming, and also for nostalgic reasons. When he was eight, his parents divorced, and he lived here part-time with his brother and father, who originally used the studio. The three of them slept on the mezzanine and ate meals from an oil stove. ‘It was super cool,’ Blatrix, now 35, recalls. ‘I have only good memories.’

His career choice was self-evident; art runs in his blood. At about the same time his dad quit painting to be a boatbuilder in Brittany, his mother became

a full-time ceramicist. Blatrix graduated from the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 2011 and rapidly found the success that had always eluded his father. In 2014, he was awarded the Prix Fondation d’Entreprise Ricard. His works have made their way into the collections of the Musée National d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, the Pinault Foundation and the Aïshti Foundation in Beirut. He earned acclaim for an installation at the most recent Frieze London and is presenting a solo show at Kunsthalle Basel this winter.

Top, the artist in his Paris studio. Bottom, A ladder leads to a mezzanine level in Blatrix’s studio.

When Blatrix has an exhibition to prepare, a demand increasing in frequency, he rents a large space in the suburbs where he assembles his installations. The Paris studio is where he creates smaller, handmade pieces, using saws and a lathe, rasps and files, planks of wood and resin. He says that art school taught him no technical skills – he learned it all on his own. He is particularly proud of his wood marquetry, which he picked up on YouTube. Blatrix’s work is difficult to define. His installations combine industrially manufactured items with his own meticulously crafted pieces to create mysterious, often futuristic ‘objects’, which he somehow imbues with emotion. Though useless, they appear to be important, vaguely resembling quotidian utilities such as cash machines or mailboxes.

‘When I saw Camille’s work for the first time at the Galerie Balice Hertling in Paris, I didn’t really understand it, which is always a good sign for me,’ says curator Guillaume Désanges. ‘There is an ambiguity between the artisanal and industrial nature of his objects that makes them cold yet sensual.’ Désanges invited Blatrix to create a solo show for the Fondation d’entreprise Hermès’ La Verrière in Brussels last autumn. The artist responded with an installation that included a tale of a seed evolving into a flower, a dental retainer and a wooden sculpture that looked like a boat hull, crafted by his father. (One of Blatrix’s earlier exhibitions included work by both his parents.)

Another independent curator, Attilia Fattori Franchini, had a similar reaction when she discovered Blatrix’s work. ‘I couldn’t figure it out,’ she says. ‘He left me thinking of something I knew and recognised, but I couldn’t understand its formalistic language.’ Intrigued, she commissioned him to create a piece for the 2019 BMW Open Work by Frieze, an annual initiative inviting artists to use the carmaker’s technology. Blatrix produced a slick white object like a car bonnet, hard on the outside and protective underneath, which seemed to be communicating with an automobile. He called the installation Sirens, a reference to the mythical creatures that bewitched Ulysses with their song. ‘I’m very drawn to the objects that surround us,’ he says. ‘Cars, phones, all those technological things that are both attractive and terrifying. It’s the concept of desire. ‘

Blatrix has an intense, slightly hyperactive energy. He talks a lot and thinks even more. His work often mixes personal experience with current events, treated with the detached perspective of an artist. ‘I like to start with ideas with a certain pathos,’ he says, ‘and then I make them increasingly abstract until the result is something more twisted and strange.’

Blatrix’s Sirens, 2019, for BMW Open Work at Frieze London.

Typically, after a period of introspection, Blatrix explains his ideas to an industrial designer friend, who maps them out in 3D. His manufacturing partner – specialists in aluminium or foam, for example – produce some pieces, while he does others by hand.

He started thinking about the upcoming Basel show last summer, during the Paris heatwaves, when he was putting his baby daughter to bed. He imagined the exhibition in a child’s room. He thought about the increasing public debate as to whether the world is coming to an end. He thought about the four seasons, and barriers – those between seasons, and those that we put up to protect our children. He planned a kind of bed as a central element, with layers matching his mental image of a weather station, covered with wood blocks like a child’s toy, and topped with marquetry. Four barriers would emulate charging stations, attached to an assortment of objects.

In early November, two-and-a-half months before the show, he was waiting for a cabinetmaker and an upholsterer to deliver the elements of the bed. From that point onwards, he would work full-time crafting objects at his studio, guided by what he calls an ‘intuitive, formal creative process’.

Blatrix says he does his most powerful work under the pressure of a deadline. It is not an easy process;

he admits it is not even very enjoyable. ‘Sometimes I think, “Shit, why did I choose sculpture?”’ he says. ‘It’s laborious. I can’t just let go and do whatever

I want. And I think this disagreeable relationship with the process takes me in a direction where I make objects that I don’t quite understand, and that don’t necessarily resemble me. Whereas if I wrote music, it would be love songs, and people would say – “Ah oui, now that is Camille.”’ Yet look closely and you might nd that under the nely engineered surface, his works are expressions of not just longing, but love.

Fortune, 2019, at Paris’ Lafayette Anticipations.

INFORMATION

‘Camille Blatrix’,

17 January – 15 March, Kunsthalle Basel. kunsthallebasel.ch

ADDRESS

Kunsthalle Basel

Steinenberg

7 CH-4051 Basel

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Amy Serafin, Wallpaper’s Paris editor, has 20 years of experience as a journalist and editor in print, online, television, and radio. She is editor in chief of Impact Journalism Day, and Solutions & Co, and former editor in chief of Where Paris. She has covered culture and the arts for The New York Times and National Public Radio, business and technology for Fortune and SmartPlanet, art, architecture and design for Wallpaper*, food and fashion for the Associated Press, and has also written about humanitarian issues for international organisations.

-

Winston Branch searches for colour and light in large-scale artworks in London

Winston Branch searches for colour and light in large-scale artworks in LondonWinston Branch returns to his roots in 'Out of the Calabash' at Goodman Gallery, London ,

-

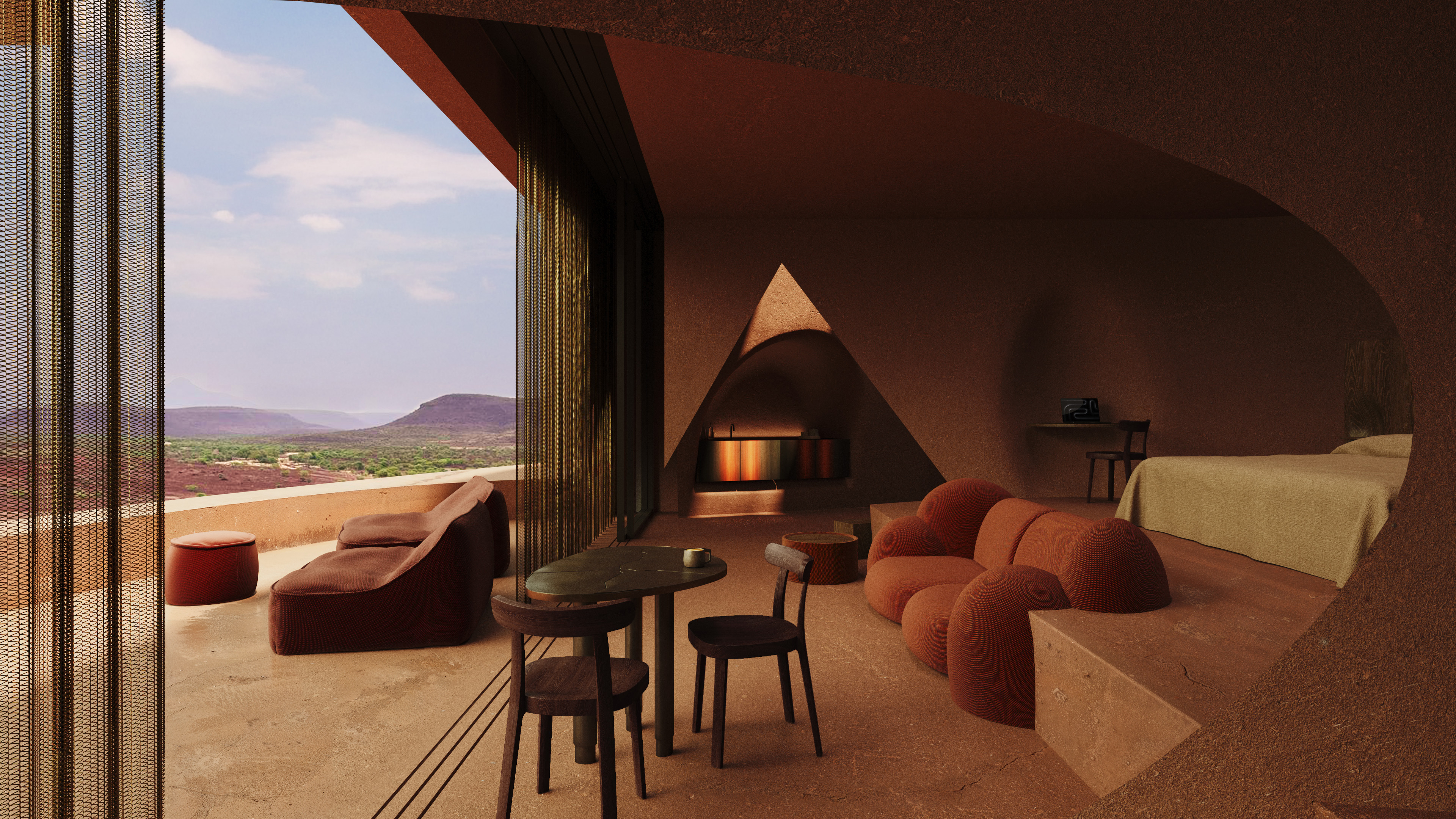

The most anticipated hotel openings of 2026

The most anticipated hotel openings of 2026From landmark restorations to remote retreats, these are the hotel debuts shaping the year ahead

-

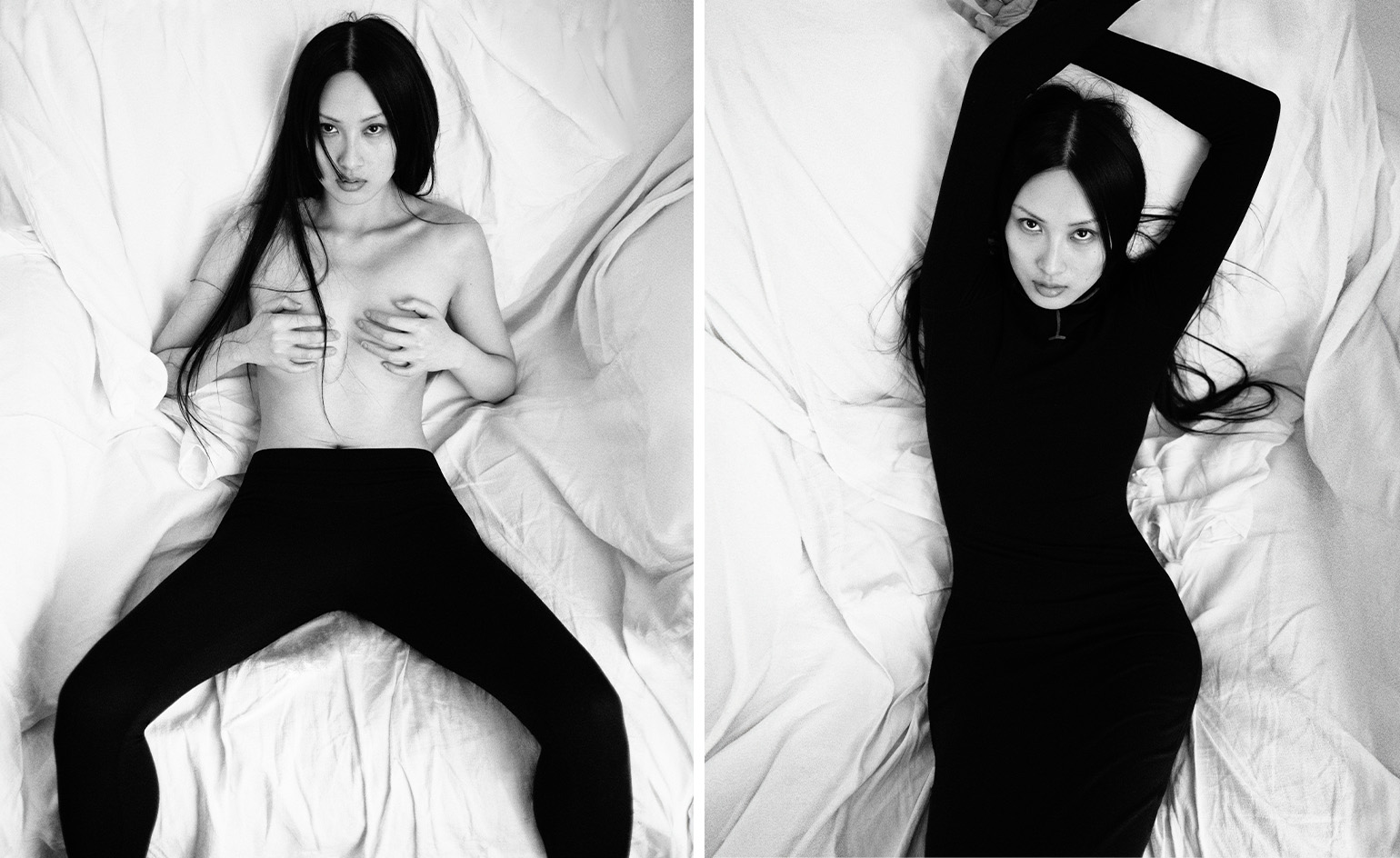

Is the future of beauty skincare you can wear? Sylva’s Tallulah Harlech thinks so

Is the future of beauty skincare you can wear? Sylva’s Tallulah Harlech thinks soThe stylist’s label, Sylva, comprises a tightly edited collection of pieces designed to complement the skin’s microbiome, made possible by rigorous technical innovation – something she thinks will be the future of both fashion and beauty

-

Rolf Sachs’ largest exhibition to date, ‘Be-rühren’, is a playful study of touch

Rolf Sachs’ largest exhibition to date, ‘Be-rühren’, is a playful study of touchA collection of over 150 of Rolf Sachs’ works speaks to his preoccupation with transforming everyday objects to create art that is sensory – both emotionally and physically

-

Architect Erin Besler is reframing the American tradition of barn raising

Architect Erin Besler is reframing the American tradition of barn raisingAt Art Omi sculpture and architecture park, NY, Besler turns barn raising into an inclusive project that challenges conventional notions of architecture

-

What is recycling good for, asks Mika Rottenberg at Hauser & Wirth Menorca

What is recycling good for, asks Mika Rottenberg at Hauser & Wirth MenorcaUS-based artist Mika Rottenberg rethinks the possibilities of rubbish in a colourful exhibition, spanning films, drawings and eerily anthropomorphic lamps

-

San Francisco’s controversial monument, the Vaillancourt Fountain, could be facing demolition

San Francisco’s controversial monument, the Vaillancourt Fountain, could be facing demolitionThe brutalist fountain is conspicuously absent from renders showing a redeveloped Embarcadero Plaza and people are unhappy about it, including the structure’s 95-year-old designer

-

See the fruits of Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely's creative and romantic union at Hauser & Wirth Somerset

See the fruits of Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely's creative and romantic union at Hauser & Wirth SomersetAn intimate exhibition at Hauser & Wirth Somerset explores three decades of a creative partnership

-

Technology, art and sculptures of fog: LUMA Arles kicks off the 2025/26 season

Technology, art and sculptures of fog: LUMA Arles kicks off the 2025/26 seasonThree different exhibitions at LUMA Arles, in France, delve into history in a celebration of all mediums; Amy Serafin went to explore

-

Inside Yinka Shonibare's first major show in Africa

Inside Yinka Shonibare's first major show in AfricaBritish-Nigerian artist Yinka Shonibare is showing 15 years of work, from quilts to sculptures, at Fondation H in Madagascar

-

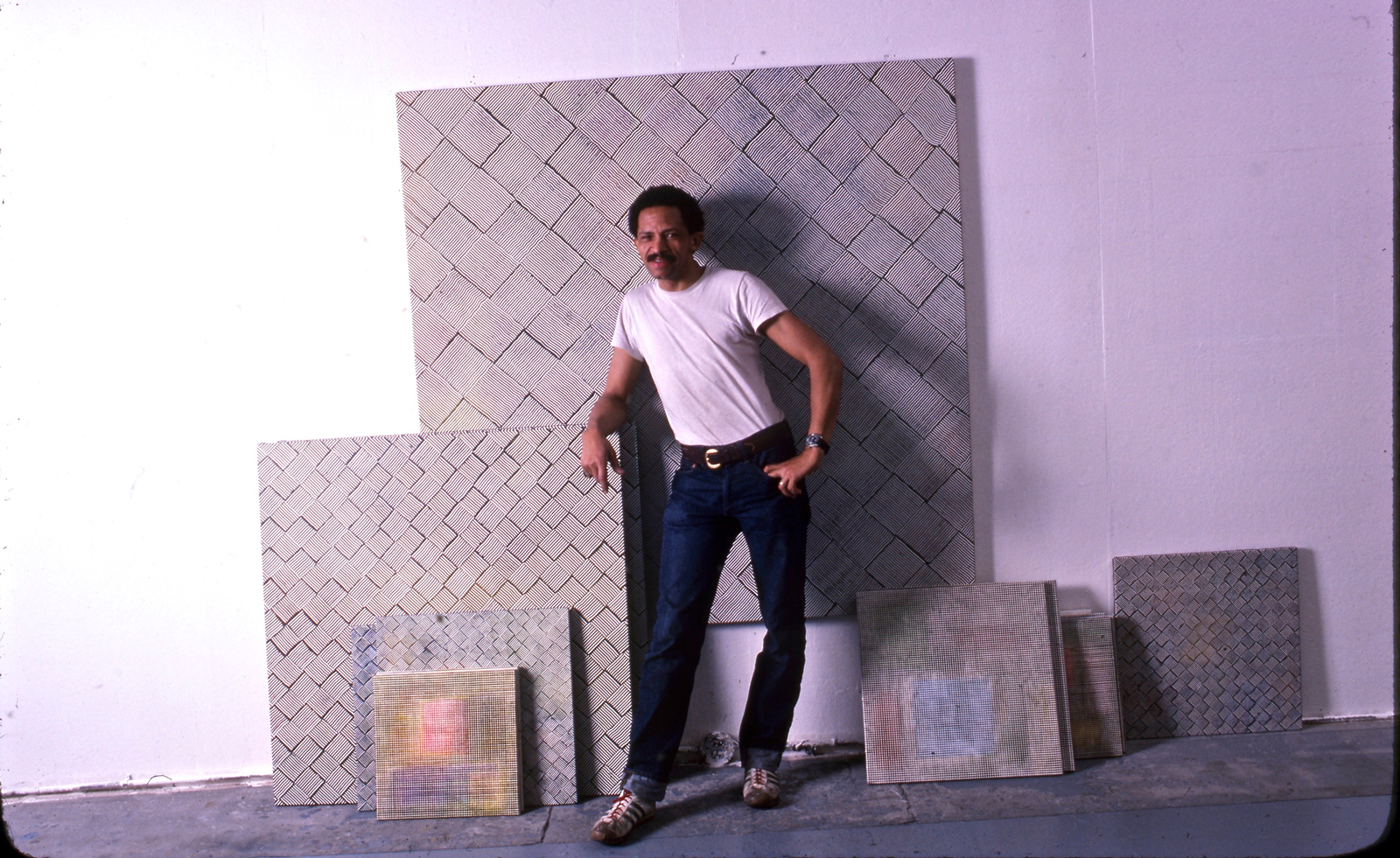

Inside Jack Whitten’s contribution to American contemporary art

Inside Jack Whitten’s contribution to American contemporary artAs Jack Whitten exhibition ‘Speedchaser’ opens at Hauser & Wirth, London, and before a major retrospective at MoMA opens next year, we explore the American artist's impact