Candida Höfer composes staggering portraits of vacant public spaces

We profile German photographer Candida Höfer, who is known for powerful large-format photographs of public spaces around the world

Candida Höfer - Photographer

Although many might call her an architectural photographer, Candida Höfer’s speciality is portraiture – but portraits of places rather than people. Her oeuvre, developed over the last 60 years, is defined by large-format colour images of the interiors of (semi-)public spaces, ranging from 17th-century baroque churches in Mexico and Germany to historic theatres in Buenos Aires and Moscow, white-walled exhibition spaces, libraries, staircases, and more. With a focus on the aura and personality of such spaces, especially when they are emptied of the humans for which they were built, Höfer has redefined how architecture is portrayed in photography.

Höfer was born in 1944 in Eberswalde, Germany, a town north-east of Berlin. In the 1960s, she studied at the Cologne Academy of Fine and Applied Arts and then worked for newspapers as a portrait photographer. She enrolled at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in 1973, where she studied under Bernd and Hilla Becher. There she began to take a more conceptual approach to photography, reflecting the Bechers’ and the Düsseldorf School of Photography’s dedication to the 1920s German tradition of Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity). Students of the Bechers learned to use photography as a conceptual tool to produce archives of places, and today this approach continues to permeate Höfer’s practice – as well as those of her contemporaries, including Thomas Struth, Andreas Gursky and Thomas Ruff.

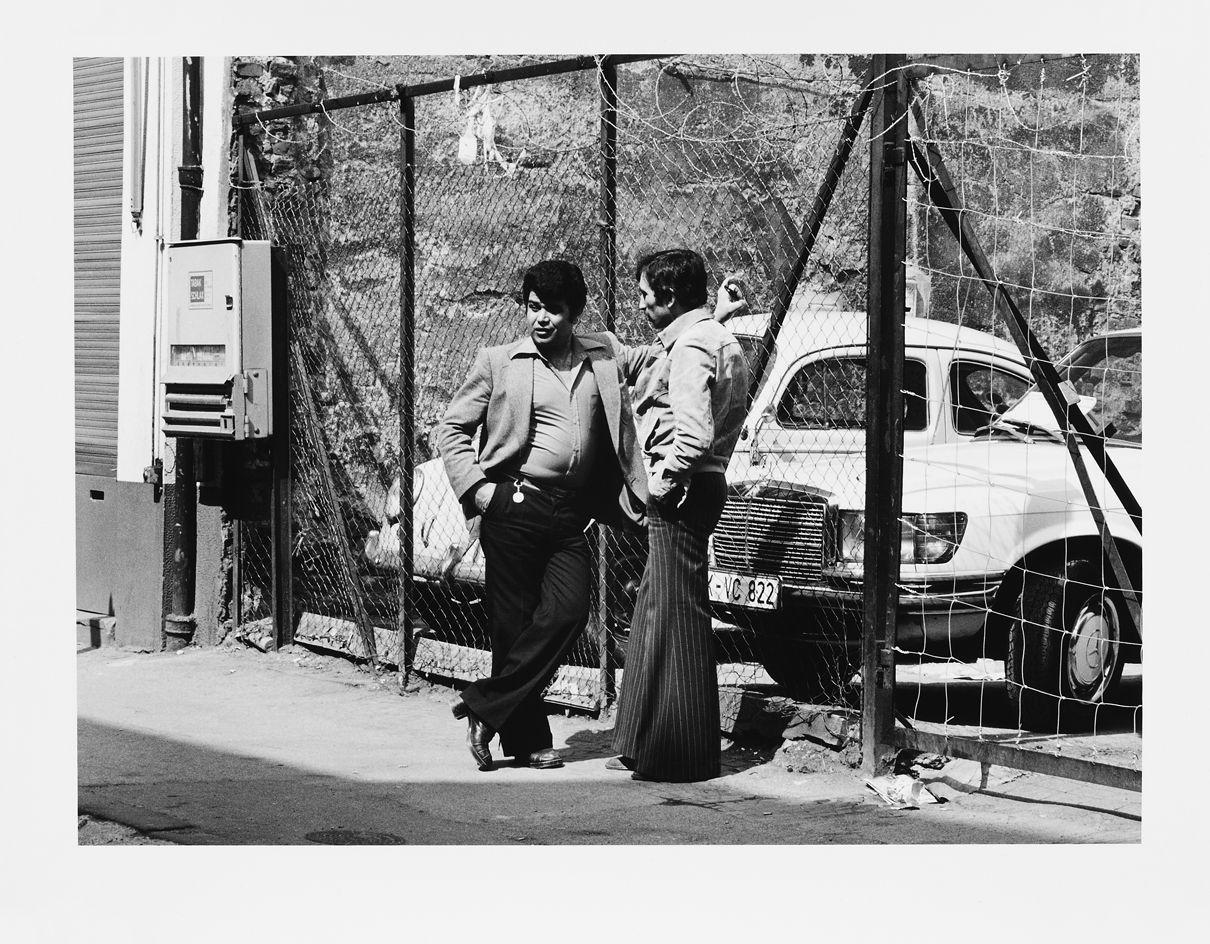

Following the trajectory of her education, Höfer photographed people in early projects such as Türken in Deutschland (Turks in Germany), a series focusing on migrant families in their new homes. But she quickly realised that humans were not her primary interest, and from 1979 onwards, her focus shifted towards public buildings. ‘I am more interested in functions for the public, rather than private histories that would make me feel like I’m intruding into people’s lives,’ she wrote in 2020.

Weidengasse Köln IV 1978 from the series Türken in Deutschland (Turks in Germany)

Höfer is especially interested in public spaces when the public is absent, in the psychological impact of design, and the contrast between a space’s intended and actual uses. ‘What people do in spaces does not necessarily conform with what spaces intend for them,’ she explains. ‘What interests me is less what is happening in a space at a given moment [and more] what a space does to the imagination. What does the space intend? What did happen, what could happen in this space? What memories does the space evoke? How would I feel being in that space? The projections of those who look at the image fill the absence.’

There is a powerful presence to be found in the absence that Höfer captures. Her large-scale images render minute details with flawless precision, so a viewer can easily imagine what it would be like to stand in the depicted spaces. In a work like Bolshoi Teatr Moskwa II 2017, one can envision standing on the stage and looking out into the audience, or imagine the backs of the historic, ornately carved wooden chairs. Conversely, in Teatro Degollado Guadalajara III 2015, the viewer enters the image from the first balcony level, overlooking the orchestra level seating and stage design. In her photographs of libraries around the world – from the Sorbonne in Paris and the Real Gabinete Português de Leitura in Rio de Janeiro to the Beinecke Library in New Haven, Connecticut – viewers can visualise wandering among towering stacks, pulling rare books and manuscripts, sitting at desks in richly-decorated halls, standing on balconies lost in thought or perhaps admiring the striking visuality of organised literature. ‘Libraries are the embodiment of visual order in a given space,’ Höfer points out. ‘At the same time, libraries offer a variety in colour and light and thoughts of possibilities to learn and to know.’ Plus, she adds, ‘I like books.’ No matter the subject, Höfer’s images transport viewers into the space at hand, with the apparent emptiness opening up the possibility for individual meditations and projections.

Bolshoi Teatr Moskwa II 2017

The meditative quality we experience when viewing Höfer’s work is reflected in her creative process, too. Since the 1970s, she has approached every space in the same way: with one assistant, a large-format camera, and nothing more – not even lighting equipment. Rather, she relies on the light in any given space, be it artificial, natural, or a combination thereof. The use of the light inherent to a space conveys its true character, just like a visitor might experience it, rather than an ambiance created via an artificial intervention. Höfer is opposed to architectural photography ‘that [visualises] architectural problem-solving or attempts to do so’. She prefers to ‘see the space as it is and [for] what it does, and less how it has become a constructed space’.

In two upcoming exhibitions – one at the Museum für Fotografie in Berlin and another at the Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein – Höfer’s work will be paired with works from the institutions’ collections. In both cases, the idea for such a pairing came from the museums, but for Höfer it was an intriguing opportunity. ‘It’s an engaging supplement to the solo show and group show, and it invites discoveries for all involved,’ she says.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library New Haven CT | 2002

In Berlin, the artistic integrity of her work will be underlined by pairings with more traditional architectural photography; in many cases, the names of the photographs’ creators remain unknown, and the images were made in service of architects and art historians rather than according to an individual’s vision.

Although Höfer returns to certain types of spaces time and again, selecting new subjects is a matter of chance. The process, she explains, ‘is a bit like meeting people and developing an interest in them; you cannot say, “I only want to meet people I have an interest in”. You meet, you see, and it clicks.’ The common thread running throughout her practice is undoubtedly public spaces, largely due to their link with ‘what society offers as social infrastructures, what political systems seek to communicate to their subjects, and what is perceived as form, as style, by political systems and their societies at a given time’. But ultimately, what guides her is instinct. ‘Looking backwards, I go forward,’ she concludes. ‘Maybe, subconsciously, there is something guiding me. But then again, this is what it is: subconscious.’

Fundaçao Bienal de São Paulo I 2005

Malkasten Düsseldorf I 2011

Teylers Museum Haarlem II 2003

Belgisches Haus Köln I 1989

Neues Museum Berlin XL 2009

INFORMATION

This article originally featured in the April 2022 issue of Wallpaper*, on newsstands now and available to subscribers.

Candida Höfer’s ‘Bild und Raum’ is at Museum für Fotografie Berlin, 25 March – 28 August, smb.museum

‘Liechtenstein’ is at Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein, 30 September 2022 – 10 April 2023, kunstmuseum.li, galeriezander.com

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss

-

MK&G’s ‘Glitter’ exhibition: a brilliant world-first tribute to sparkle and spectacle

MK&G’s ‘Glitter’ exhibition: a brilliant world-first tribute to sparkle and spectacleMK&G’s latest exhibition is a vibrant flurry of sparkles and glitter with a rippling Y2K undercurrent, proving that 'Glitter is so much more than you think it is'

By Hiba Alobaydi

-

Inside E-WERK Luckenwalde’s ‘Tell Them I Said No’, an art festival at Berlin's former power station

Inside E-WERK Luckenwalde’s ‘Tell Them I Said No’, an art festival at Berlin's former power stationE-WERK Luckenwalde’s two-day art festival was an eclectic mix of performance, workshops, and discussion. Will Jennings reports

By Will Jennings

-

Alexandra Pirici’s action performance in Berlin is playfully abstract with a desire to address urgent political questions

Alexandra Pirici’s action performance in Berlin is playfully abstract with a desire to address urgent political questionsArtist and choreographer Alexandra Pirici transforms the historic hall of Berlin’s Hamburger Bahnhof into a live action performance and site-specific installation

By Alison Hugill

-

Cyprien Gaillard on chaos, reorder and excavating a Paris in flux

Cyprien Gaillard on chaos, reorder and excavating a Paris in fluxWe interviewed French artist Cyprien Gaillard ahead of his major two-part show, ‘Humpty \ Dumpty’ at Palais de Tokyo and Lafayette Anticipations (until 8 January 2023). Through abandoned clocks, love locks and asbestos, he dissects the human obsession with structural restoration

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Year in review: top 10 art interviews of 2022, chosen by Wallpaper* arts editor Harriet Lloyd-Smith

Year in review: top 10 art interviews of 2022, chosen by Wallpaper* arts editor Harriet Lloyd-SmithTop 10 art interviews of 2022, as selected by Wallpaper* arts editor Harriet Lloyd-Smith, summing up another dramatic year in the art world

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Yayoi Kusama on love, hope and the power of art

Yayoi Kusama on love, hope and the power of artThere’s still time to see Yayoi Kusama’s major retrospective at M+, Hong Kong (until 14 May). In our interview, the legendary Japanese artist vows to continue to ‘create art to leave the message of “love forever”’

By Megan C Hills

-

Antony Gormley interview: ‘We’re at more than a tipping point. We’re in a moment of utter crisis’

Antony Gormley interview: ‘We’re at more than a tipping point. We’re in a moment of utter crisis’We visit the London studio of British sculptor Antony Gormley ahead of his major new show ‘Body Field’ at Xavier Hufkens Brussels

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Photographer Maisie Cousins on nostalgia, impulsive making and ‘collecting useless things’

Photographer Maisie Cousins on nostalgia, impulsive making and ‘collecting useless things’Explore the vision of British artist Maisie Cousins in ‘Through the lens’, our monthly series spotlighting photographers who are Wallpaper* contributors

By Sophie Gladstone