Cannes Film Festival 2024 highlights: our verdict is in

What to watch or not to watch – cut to the Cannes Film Festival 2024 highlights

It was a strange year at the Cannes Film Festival. The most anticipated title landed with a deafening thud and plenty of films were fine but underwhelming, before a couple of incognito gems lit up the Croisette and saved the day.

The film most critics felt compelled to watch was Francis Ford Coppola’s Megalopolis, a 40-years-in-the-making experimental sci-fi with a $120 million price-tag partially funded by Coppola’s selling one of his vineyards (fortunately he has more). Adam Driver stars as a priapic, time-pausing architect, Cesar Catalina, whose life’s work is to build a utopia out of the dystopia that is the decadent and divided New Rome. This clunky epic left me without any critical convictions. Who can hate a grand folly that a man sold his vineyard to fund? Yet, I cannot say it was well made, coherent or truly interesting, even if it does offer further proof that Aubrey Plaza can do no wrong. Here, she shines as ‘Wall Street slut’ Wow Platinum. But, onto the good stuff!

Cannes Film Festival 2024 highlights

All We Imagine As Light

All We Imagine As Light

Payal Kapadia’s fiction feature debut and the first Indian film to play in the Cannes competition for 30 years is like being enveloped in a dream. It is such a pleasure to be invited into Kapadia’s perspective that her piercing social commentaries on religion and class almost go unnoticed as they subtly infuse the anecdotal narrative structure. Kani Kusruti and Divya Prabha star as Prabha and Anu, two nurses who live and work together in the city of Mumbai. Anu is madly and secretly in love with her Muslim boyfriend, Shiaz. An early scene juxtaposes her pragmatic handling of a female patient with the reverie drummed up as she texts Shiaz, channelling romance through the clouds in the sky. Prabha, meanwhile, exists in a state of suspended animation and yearning. Her husband, through an arranged marriage, left to work in Germany and has not been in touch for a year.

Their contrasting romantic fates offer surging intrigue. However, the film is equally interested in these women as individuals, as friends and as city dwellers, frequently capturing them in moments of private repose or motion. As much as this is a character study and a city symphony, it’s also a masterclass in photography. Each composition is full of intimate details that are incredibly moving and the whole builds to a third act that makes sense of all these ineffable moving parts. All We Imagine As Light was awarded the Grand Prix (second prize) by the Greta Gerwig-led jury, losing out on the Palme d’Or to Sean Baker’s patchy sex-worker dramedy, Anora – but then Cannes is not renowned for its awards justice. Indeed, cartoons fly-posted around the French Riviera town invite Thierry Frémaux, who has worked at the festival for 23 years – 17 of those in the top job – to retire.

Les Balconettes

Les Balconettes

Far from the alluring daytime slots and repeat screenings of the films competing for the Palme d’Or, a small clutch of Midnight Movies offer some gore to help attendees to wash down so much prestige cinema. Within this strand, Noémie Merlant, an actress best known for Céline Sciama’s sapphic tour-de-force, Portrait of a Lady on Fire, showed just how weird and wonderful her own directorial urges are. Set in a Marseille block of flats during a heatwave, this is a riotous female revenge drama in which violent men are given quadruple the dose of their own medicine. Merlant makes the most of this deceptively simple premise by creating a friendly comic tone, so when the blood begins to flow, it is within an endearing and triumphant register.

Nicole (Sanda Codreanu), Ruby (Souheila Yacoub) and Élise (Merlant) are a close yet contrasting trio of female friends. Nicole is a jumpy writer, prone to daydreaming about the hunk in an opposite flat. Ruby is a free-spirited cam girl covered in body art and Élise is an actress, who pulls up in a hurry and a platinum Marilyn wig, having fled the set and her overbearing husband. The rapport between these performers is what gives Les Balconettes its spine and its heart. All the genre violence is held in place by an offbeat and plausible sense of camaraderie, perhaps a testament to Sciama’s screenplay credit. This attention to the vibe is not just contained in the writing and the performances; Merlant has approached production design and costumes with an Almodóvar-ian appreciation for female flair.

Julie Keeps Quiet

Julie Keeps Quiet

Critics Week is amongst the most overlooked sections of the Cannes Film Festival due to the location of its screening venue – The Miramar – a little far from the madding crowds. Nonetheless, this section, in 2016, gave us Raw by future Palme d’Or winner Julia Ducournau, and, in 2022, Aftersun by the new toast of British cinema, Charlotte Wells. The major discovery of 2024 is the feature debut by Belgian director Leonardo Van Dijl, a rigorously executed tennis drama that leaves Challengers in the chalk dust.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Newcomer and real-life tennis demon Tessa Van den Broeck plays Julie, a laconic teenager who speaks through her racket. She is the cream of her elite tennis club by such a margin that she has a scholarship there. The arc of the film is Julie internally processing why Coach Jeremy has been suspended in the run-up to an important competition. Despite his absence from the club, he continues to coach her over the phone and in clandestine meet-ups. Through these exchanges and the increasingly serious investigation at the club, the nature of his abuses of power move from abstract to likely. This film is a true marvel – too poised for any histrionics that most other entrants into this genre succumb to, it also thrives as a portrait of a person who, even at a young age, has the discipline to relitigate a previously crucial attachment at her own speed. Van Dijl mirrors Julie’s mode of existence, letting scenes of tennis and family life play out, amidst the restrained wrangling with what Jeremy did and why Julie kept quiet.

Miséricorde

Miséricorde

The refrain of 'This should have been in competition!' is earned by Alain Guiraudie’s comedy/drama/mystery/existential lament. This brilliant film is the standout that made me most excited about the possibilities of cinema by virtue of being utterly unpredictable and in possession of a scope that defies those humble articles we call words. Rocking up to his Cannes premiere in a terracotta suit, the French law-unto-himself, Guiraudie, danced into a room of admirers loyally built up by the likes of his queer Hitchcockian thriller, Stranger By The Lake.

The pleasure of Miséricorde is in the tricks it has up its sleeve and it is best to go in as cold as you can. It is safe to reveal only the basic premise. Jérémie (Félix Kysyl) returns to a tiny village to attend the funeral of his former boss, staying with the freshly widowed Martine (familiar French actress Catherine Frot). The past exerts a magnetism and Martine likes him too much so he stays for longer than anticipated, to the chagrin of Martine’s pugilistic son, Vincent (Jean-Baptiste Durand). Guiraudie plays his cards close to his chest for the first 30 minutes, introducing us to curious characters like a pastiche-quaffing local priest while confining the action to Jérémie striding impassively through the countryside. It’s possible to believe, at this point, that this is a sprawling and low-key depiction of village life; however, Guiraudie has so much more to explore. This runs the gamut from absurd hilarity to tragic loneliness to sexual farce, delving into ideas about the philosophy of crime and the forgivingness of desire. He wastes not a single character and not a single scene, resulting in an inexplicable caper that drums up an emotional weather that is so much more expansive than it has a right to be. The single best scene of the festival takes place when roles are reversed within a confession booth.

To A Land Unknown

To A Land Unknown

This year we decided to host a festival without polemics, to make sure that the main interest for us all to be here is cinema,' said Thierry Frémaux, in a pre-Cannes press conference, forgetting that in 2022, following Russia's invasion of Ukraine, he himself had invited the Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy to speak via video link at the Cannes opening ceremony. Now, he lamented that issues of political and social justice are on our collective minds. 'In the past, people only talked about the cinema. We as organisers only had one anxiety – the films: will people like them, will people hate them?' Concurrently, the Mayor of Cannes, David Lisnard, placed a ban on demonstrations on the Croisette. The scene was set to see off both the MeToo protests potentially launched by Judith Godrèche’s revelations (her short film, Moi Aussi, features testimonies of sexual abuse within the film industry) and the Palestine solidarity demonstrations that cut a dash through the Berlinale. Frémaux’s bogus claim that cinema exists in a rarefied bubble floating above politics-induced pain and bloodshed shines a light on his arrogance and his irrelevance. But – fortunately for us – cinema itself does not compartmentalise in this way.

To A Land Unknown is the first foray into fictional filmmaking by Palestinian-Danish director Mahdi Flefiel, following on from his gorgeous and heartbreaking 2012 documentary feature, A World Not Ours. It plunges us into the limbo land of Athens, where Palestinian cousins Chatila (Mahmood Bakri) and Reda (Aram Sabbah) are desperate to make it to Germany, where they hope that normal life will begin. Abandoned by people smugglers, they are without papers halfway to their desired destination, and resorting to petty crime to build up the funds to pay the blackmarket way onwards. This taut thriller blooms in the relationship dynamic between Chatila and Reda. They are bound by their shared history and homeland and fraught by their contracting temperaments. Fleifel does not exploit these characters to move the plot along, he lets us sink into their souls and dreams, their frustrations and heartbreaks. Bakri exists on screen like a man on fire, willing to do almost anything to keep moving towards the green dot on the horizon. Even though this film was made after 7 October, Fleifel does not spoon-feed us what Fremaux would call 'polemics', instead he creates a type of cinema that is coloured by a distinctly Palestinian political reality while also vast enough to speak to souls in limbo everywhere.

Sophie Monks Kaufman is a film writer and editor who has contributed to Little White Lies, Sight & Sound and The Independent.

-

A Xingfa cement factory’s reimagining breathes new life into an abandoned industrial site

A Xingfa cement factory’s reimagining breathes new life into an abandoned industrial siteWe tour the Xingfa cement factory in China, where a redesign by landscape specialist SWA Group completely transforms an old industrial site into a lush park

By Daven Wu

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Unlike the gloriously grotesque imagery in his films, Yorgos Lanthimos’ photographs are quietly beautiful

Unlike the gloriously grotesque imagery in his films, Yorgos Lanthimos’ photographs are quietly beautifulAn exhibition at Webber Gallery in Los Angeles presents Yorgos Lanthimos’ photography

By Katie Tobin

-

‘Life is strange and life is funny’: a new film goes inside the world of Martin Parr

‘Life is strange and life is funny’: a new film goes inside the world of Martin Parr‘I Am Martin Parr’, directed by Lee Shulman, makes the much-loved photographer the subject

By Hannah Silver

-

The Chemical Brothers’ Tom Rowlands on creating an electronic score for historical drama, Mussolini

The Chemical Brothers’ Tom Rowlands on creating an electronic score for historical drama, MussoliniTom Rowlands has composed ‘The Way Violence Should Be’ for Sky’s eight-part, Italian-language Mussolini: Son of the Century

By Craig McLean

-

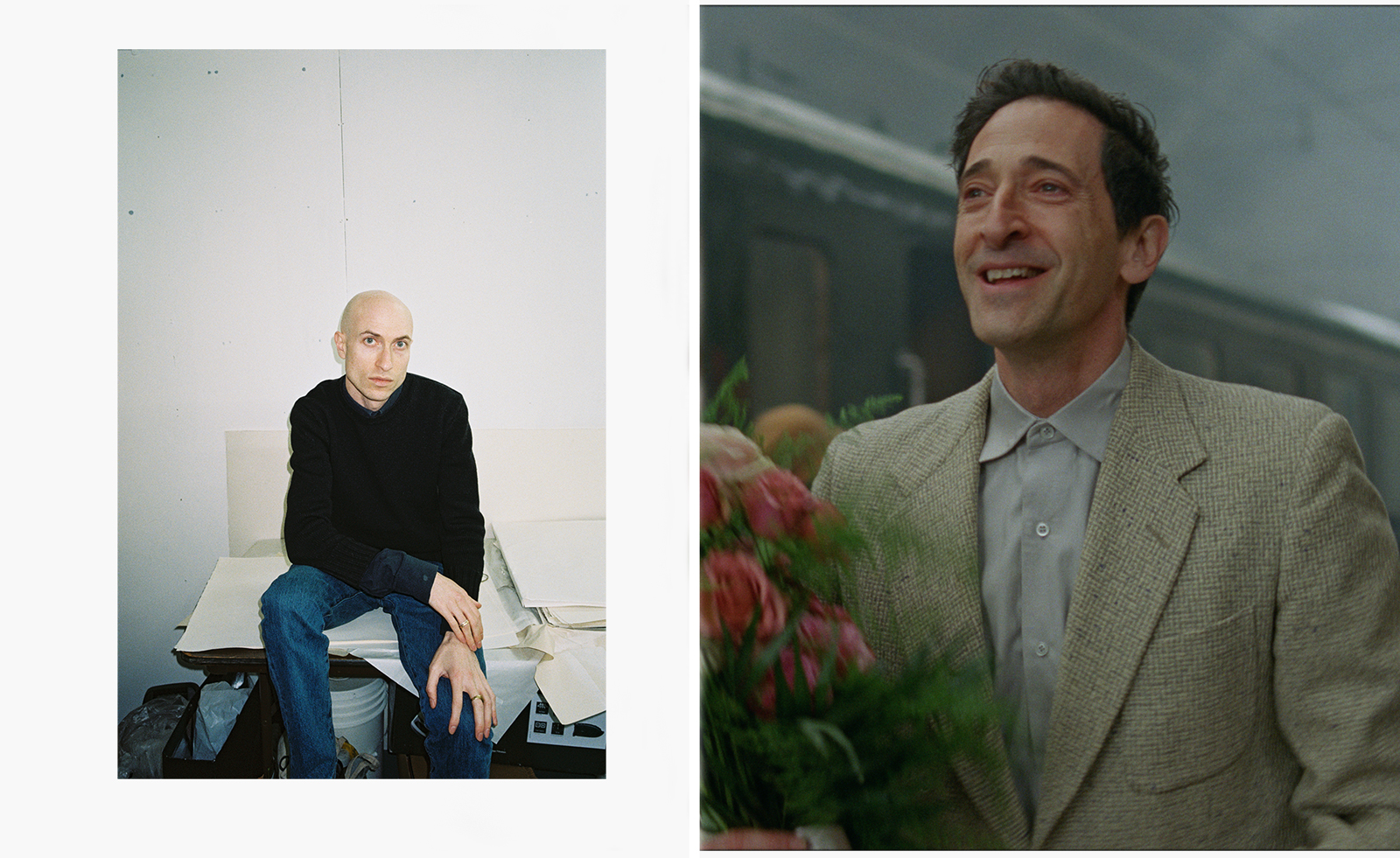

Meet Daniel Blumberg, the British indie rock veteran who created The Brutalist’s score

Meet Daniel Blumberg, the British indie rock veteran who created The Brutalist’s scoreOscar and BAFTA-winning Blumberg has created an epic score for Brady Corbet’s film The Brutalist.

By Craig McLean

-

Remembering David Lynch (1946-2025), filmmaking master and creative dark horse

Remembering David Lynch (1946-2025), filmmaking master and creative dark horseDavid Lynch has died aged 78. Craig McLean pays tribute, recalling the cult filmmaker, his works, musings and myriad interests, from music-making to coffee entrepreneurship

By Craig McLean

-

Architecture and the new world: The Brutalist reframes the American dream

Architecture and the new world: The Brutalist reframes the American dreamBrady Corbet’s third feature film, The Brutalist, demonstrates how violence is a building block for ideology

By Billie Walker

-

‘It creates mental horrors’ – why The Thing game remains so chilling

‘It creates mental horrors’ – why The Thing game remains so chillingWallpaper* speaks to two of the developers behind 2002’s cult classic The Thing video game, who hope the release of a remastered version can terrify a new generation of gamers

By Thomas Hobbs

-

Wu Tsang reinterprets Carmen's story in Barcelona

Wu Tsang reinterprets Carmen's story in BarcelonaWu Tsang rethinks Carmen with an opera-theatre hybrid show and a film installation, recently premiered at MACBA in Barcelona (until 3 November)

By Emily Steer