Collezione Maramotti’s extraordinary art collection continues to evolve

The converted factory gallery in Reggio Emilia presents the first rehang of its permanent collection since it opened in 2007

Max Mara’s late founder Achille Maramotti was born and bred in the Italian city of Reggio Emilia, best known for being the progenitive city of the famed Reggio Emilia approach to educational philosophy. Now, growing this local legacy in forward-thinking discussion, the Collezione Maramotti is one of the most important – and intelligent – contemporary art collections in the country.

The building, first built as a Max Mara factory in 1957 by the architecture firm of Antonio Pastorini and Eugenio Salvarani, was converted into a gallery between 2003 and 2007 by English architect Andrew Hapgood. The building, and its contents, are kept under the close watch by its protective family owners, spearheaded by Luigi Maramotti, Achille's son and the chairman of Max Mara. Though free to enter (at the wishes of Achille), the Collezione is reserved for appointment-only guests (of up to 25 people at a time) and no children under 11. ‘Visitors must take their time and spend a couple of hours to see it,' explains the Collezione's senior coordinator Sara Piccinini. ‘That’s what we request: to enter into a personal relationship with the works’.

We first visited back in 2009 for the March fashion special of Wallpaper* (W*120). ‘The gallery may reveal occasional glimpses of its founder's idiosyncratic character,’ we wrote at the time, ‘but ultimately it conceals as much as it reveals’. In places, evidence of its former life as a factory has been retained; in the floors, stained by the memory of machinery long-removed, and in the Memphis-style cafeteria, with its gloriously vibrant orange booths and checkered tables. Elsewhere, in the sweeping reception hall opened up by Hapgood, and the architectural, slatted windows that tesselate across the facade, this is a polished, world-class art gallery.

The Collezione Maramotti, as pictured in the March 2009 issue of Wallpaper*. The building was one of the first to contrast raw reinforced concrete with exposed brickwork on its exterior.

Over the last few years, the collection seems to be openings itself up, and revealing precious more about its ethos and environments. Last year, for example, the Collezione Maramotti played host to its first Max Mara fashion show (the Resort 2019 collection), where the visceral work of Lutz & Guggisberg’s debut Italian exhibition provided textural counterpoint to the double-faced cashmere, gauzy silk organza of the collection.

Indeed, art and fashion continually cohabit within the Max Mara identity. ‘From the very start, Achille Maramotti thought that there may be a fruitful interchange between artistic creativity and industrial design: some of the art pieces were on display in the premises of Max Mara when the company was here, to positively inspire designers and creative collaborators,’ Piccinini continues. ‘But at the same time he had clearly in mind the intrinsic differences between these two languages: the artistic gesture and artworks are an end in themselves, they don’t need any reason, while fashion, as exclusive as it may be, only exists because a user exists, someone who will wear it.’

A good example: since 2005, the brand has sponsored the biannual Max Mara Art Prize for Women in collaboration with London's Whitechapel Gallery. In 2016, a fascinating show by artist Emma Hart drew upon the academic legacy of Reggio Emilia. She spent six months in the town, and travelling Italy, immersing herself in its culture, theory, and academia.

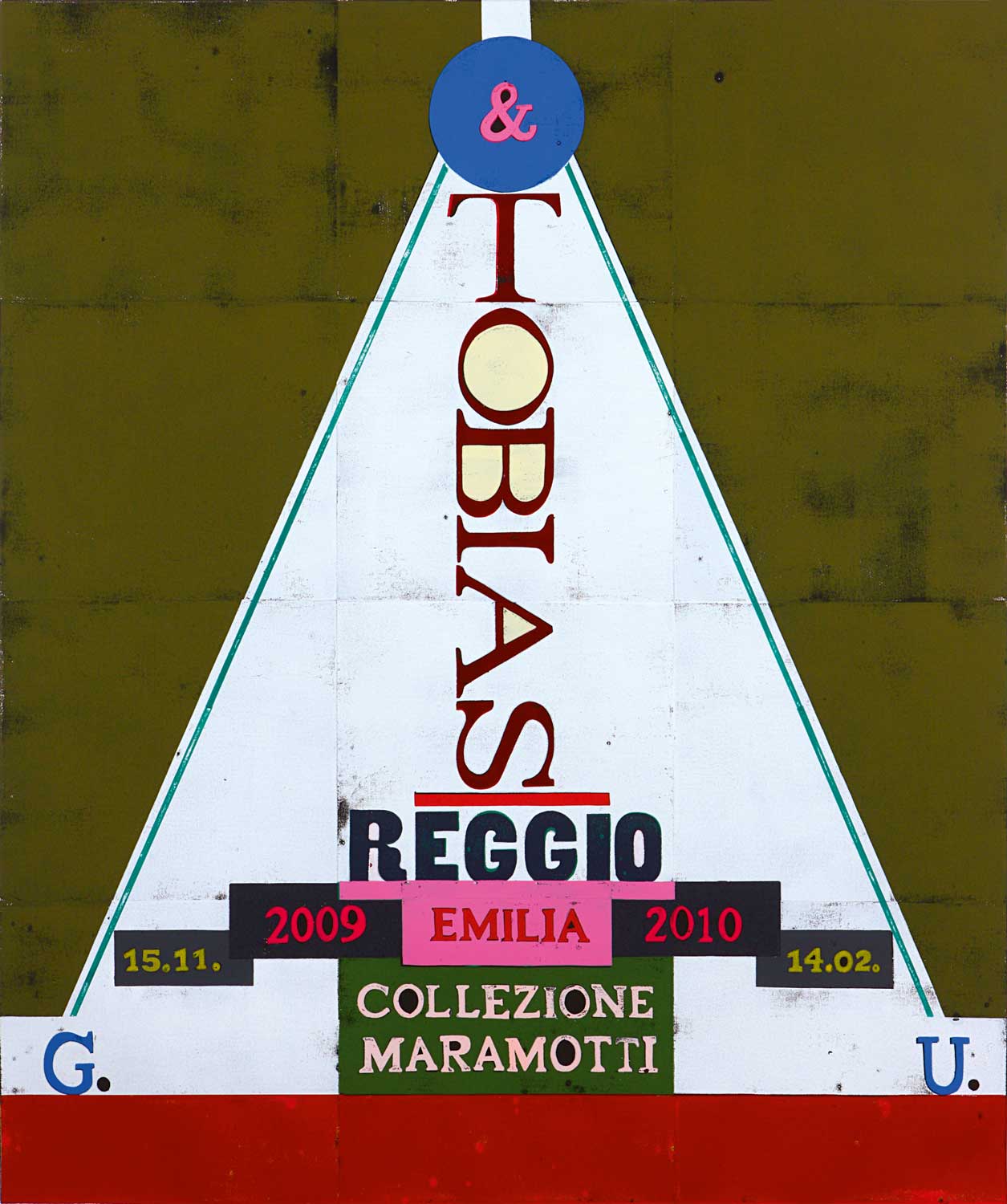

Ohne Titel, 2009, by Gert & Uwe Tobias.

Likewise, the collection is proudly Italian, and has particular strength in Italy's colourful postwar optimism; though it also presents an elegant chronology of key moments in both European and American contemporary art. The permanent collection features around 200 works from the late 1940s onwards, belonging to some of the most significant artistic trends of the second half of the 20th century: art informel, arte povera, German and American neoexpressionism, New Geometry, alongside more recent experimentations from the 1990s. Continuing to chart and represent emerging movements, the new exhibition ‘Rehang’ emphasises the family's restless fascination with the new, with a selection of works created by today’s bleeding-edge.

In the exhibition, the work of ten artists that exhibited at the Collezione since it opened to the public in 2007 have been rehung in new contexts. Solo shows from Enoc Perez, Gert & Uwe Tobias, Jacob Kassay, Krištof Kintera, Jules de Balincourt, Alessandro Pessoli, Evgeny Antufiev, Thomas Scheibitz, Chantal Joffe and Alessandra Ariatti, pick up notes central to the collection, particularly its keen eye for the evolution of painting.

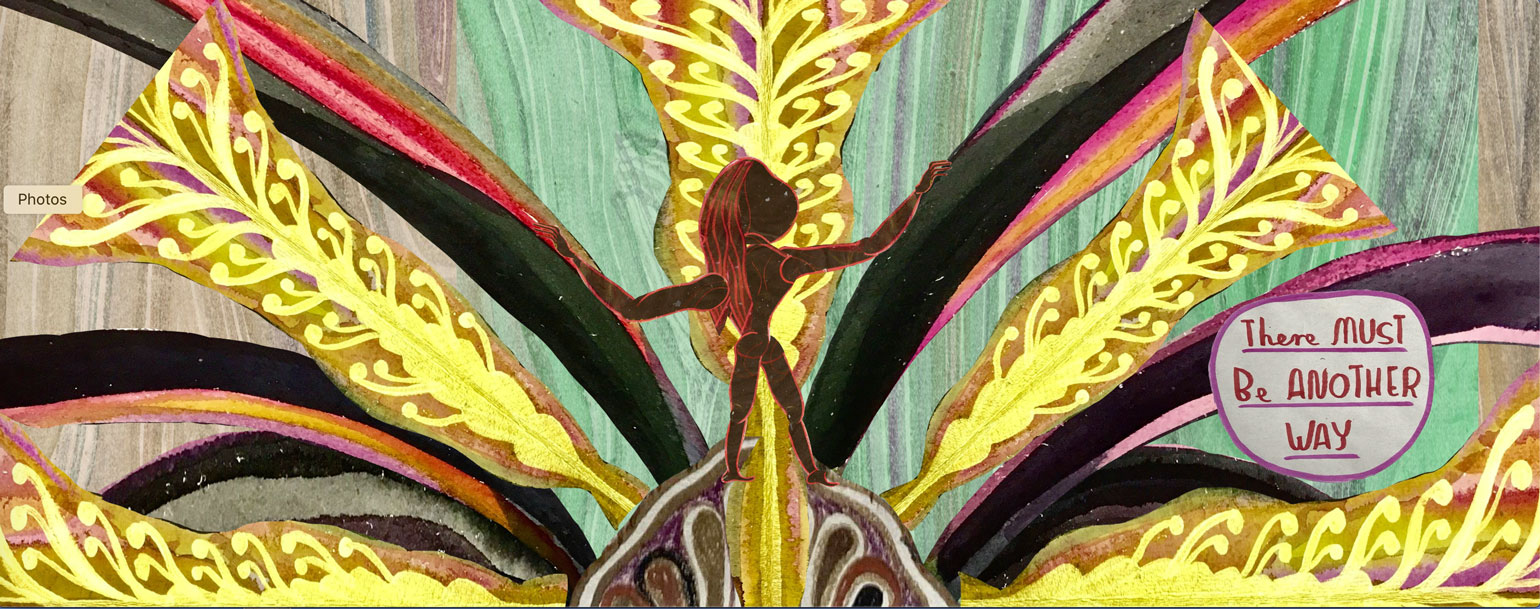

Joffe's paintings are equal parts seductive and arresting. In the four large format paintings on display, the British artist represents a large single figure, her then-teenager niece Moll, an Alice in Wonderland-esque figure, with enigmatic qualities. Through broad brushstrokes and blurred details of the face and dresses, the girl looks immersed in a dense, pictorial flow.

Installation view of Jacob Kassay’s 2010 exhibition, ‘Untitled’. Courtesy of Collezione Maramotti, Reggio Emilia, 2019.

Elsewhere, Jacob Kassay's silvery painted sheets (pictured above) act as an antidote to the almost overwhelming range of work on show throughout the museum. His room, filled with nine mirror-like works, is cast in a moonlit atmosphere; each individual painting contributing to a kind of peaceful immersion.

Interestingly, the collection doesn't have a curator, as such, and never has. Instead, the artists themselves play a keen role in directing the hanging of the works, and the flow of their exhibitions. All ten artists featured in Rehang attended the private view, indicating their level of engagement. The lack of curatorial input, too, reveals the extend that the Maramotti family contribute to exhibitions. They play a crucial role. ‘The Maramotti family enter into conversations with the artists and make decisions about the shows to present, as well as the artworks to purchase; taking care of the daily dialogue with artists, supporting them step by step and making projects happen,’ Piccinini says. ‘The dialogue and the continuous interaction between these roles is the core of our working practice.’

Moll with the Cat, 2014, by Chantal Joffe.

From the 2011 exhibition ‘Il fiume e le sue fonti’, by Thomas Scheibitz. Courtesy of Collezione Maramotti, Reggio Emilia, 2019.

Installation view of Gert & Uwe Tobias’ 2009 exhibition. Courtesy of Collezione Maramotti, Reggio Emilia, 2019.

INFORMATION

‘Rehang’ continues until 28 July 2019. For more informarion, visit the Maramotti Collezione website

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Elly Parsons is the Digital Editor of Wallpaper*, where she oversees Wallpaper.com and its social platforms. She has been with the brand since 2015 in various roles, spending time as digital writer – specialising in art, technology and contemporary culture – and as deputy digital editor. She was shortlisted for a PPA Award in 2017, has written extensively for many publications, and has contributed to three books. She is a guest lecturer in digital journalism at Goldsmiths University, London, where she also holds a masters degree in creative writing. Now, her main areas of expertise include content strategy, audience engagement, and social media.

-

Nikos Koulis brings a cool wearability to high jewellery

Nikos Koulis brings a cool wearability to high jewelleryNikos Koulis experiments with unusual diamond cuts and modern materials in a new collection, ‘Wish’

By Hannah Silver

-

A Xingfa cement factory’s reimagining breathes new life into an abandoned industrial site

A Xingfa cement factory’s reimagining breathes new life into an abandoned industrial siteWe tour the Xingfa cement factory in China, where a redesign by landscape specialist SWA Group completely transforms an old industrial site into a lush park

By Daven Wu

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

‘I am almost an anti-sculptor’: Dominique White on her Whitechapel Max Mara Art Prize show

‘I am almost an anti-sculptor’: Dominique White on her Whitechapel Max Mara Art Prize showThe artist mines the ocean to explore Afrofuturism in ‘Deadweight’, opening at London’s Whitechapel and detailed in a new film

By Amah-Rose Abrams

-

Dominique White wins Max Mara Art Prize for Women 2022 – 2024

Dominique White wins Max Mara Art Prize for Women 2022 – 2024Artist Dominique White has been crowned winner of the ninth edition of the Max Mara Art Prize for Women, presented in a ceremony at Whitechapel Gallery

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Emma Talbot explores Greek myth and femininity at Whitechapel Gallery

Emma Talbot explores Greek myth and femininity at Whitechapel GalleryIn ‘The Age/L’Età’, her Max Mara Art Prize show at Whitechapel Gallery, Emma Talbot imagines a reality where violence is overturned by resolution, nurtured by an elderly female protagonist

By Martha Elliott

-

Emma Talbot on optimism, feminism and reconfiguring the roots of power

Emma Talbot on optimism, feminism and reconfiguring the roots of powerThe British artist and winner of the eighth Max Mara Art Prize for Women illuminates Piccadilly Circus with optimism and confronts perceived shame around female ageing

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

A tribe of Emma Hart's decapitated ceramic skulls swing into the Whitechapel gallery

A tribe of Emma Hart's decapitated ceramic skulls swing into the Whitechapel galleryBy Elly Parsons

-

Canine connection: William Wegman’s Dogs in Coats is travelling to Max Mara boutiques across the US

Canine connection: William Wegman’s Dogs in Coats is travelling to Max Mara boutiques across the USBy Pei-Ru Keh

-

Commedia show: Max Mara prizewinner Corin Sworn takes a theatrical turn

Commedia show: Max Mara prizewinner Corin Sworn takes a theatrical turnBy Florence Waters

-

Corin Sworn wins the Max Mara Art Prize for Women

Corin Sworn wins the Max Mara Art Prize for WomenBy Nick Compton