A definitive Cy Twombly retrospective reasserts his status as a modern master

In the autumn of 1963, John F Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas. His wife, Jackie Kennedy, was wearing a strawberry pink suit at the time. She famously insisted on wearing it – still stained with his blood – during the swearing-in of Lyndon B Johnson and for the flight back to Washington DC with the president’s body.

It was this pivotal event – and sartorial detail – that the late American painter Cy Twombly devoted a cycle of paintings to immediately after. The 1963 series Nine Discourses on Commodus would go on show the following spring at Leo Castelli’s gallery in New York. As the story goes, Twombly didn’t travel with the works and they were installed without him in the wrong order. Critics vehemently derided the exhibition. Donald Judd wrote a ‘killer review’; others proclaimed they were ‘old-fashioned’ and ‘too European’.

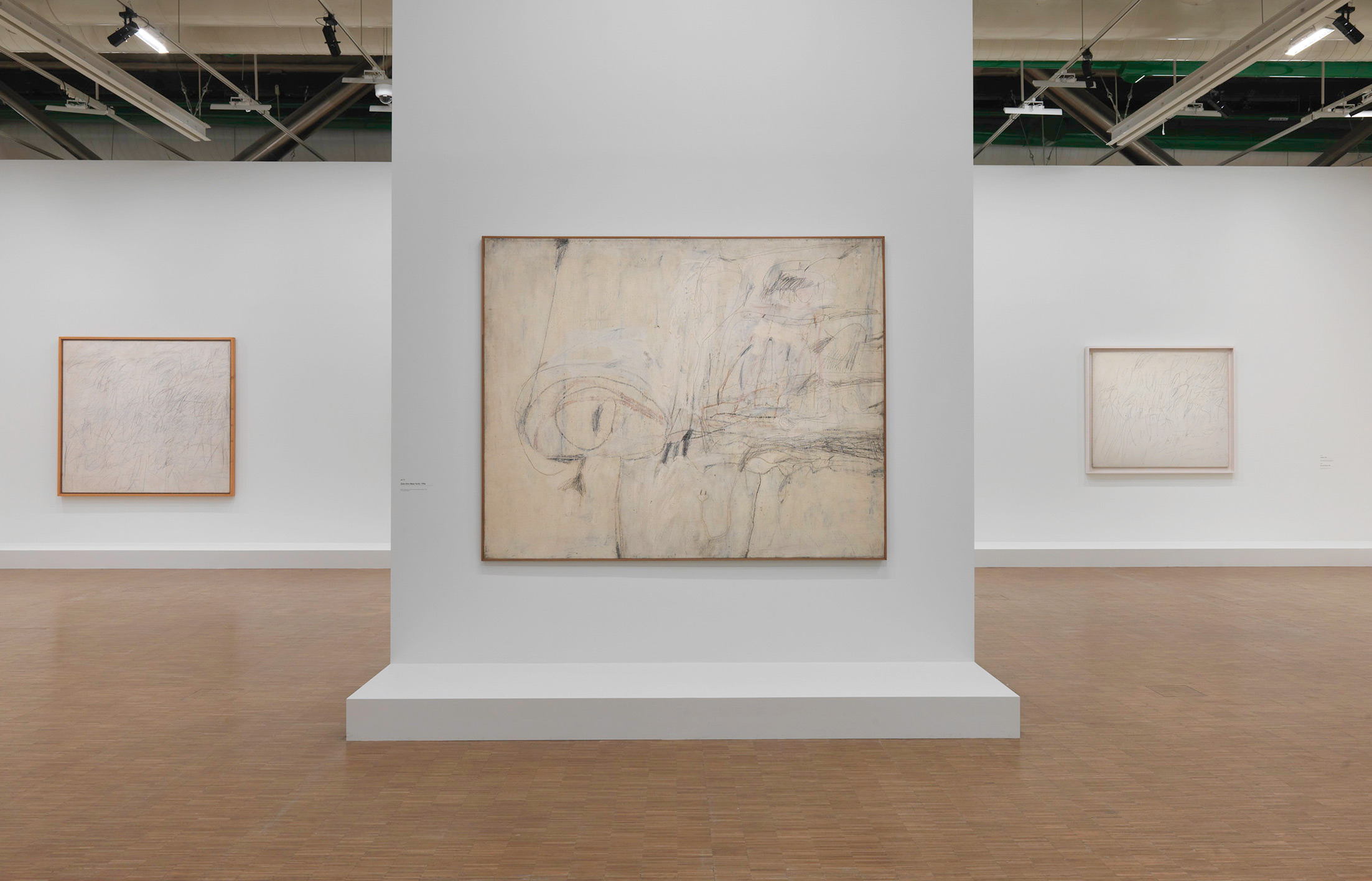

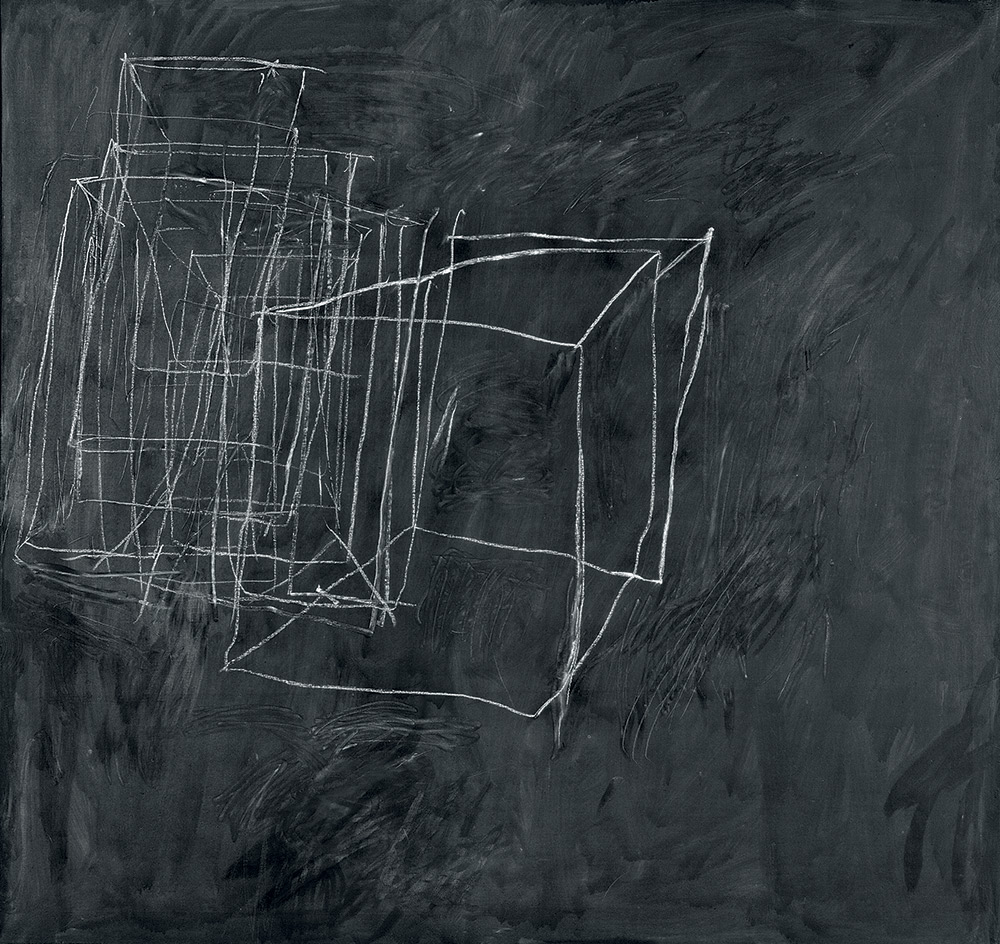

‘Volubilis’, 1953.

Now, these remarkable works are on display at the Centre Pompidou as part of a definitive retrospective opened in Paris, the first since the artist’s death in 2011. Centred on three major cycles – the aforementioned Nine Discourses on Commodus; Fifty Days at Iliam (1978); and Coronation of Sesostris (2000) – the survey spans Twombly’s 60-year career through some 140 paintings, drawings, photographs and sculptures mapped out chronologically.

Born in 1928 in Lexington, Virginia, Edwin Parker Twombly adopted his father’s nickname, ‘Cy’ (after the baseball player Cyclone Young). His affinity for art formed early on, nourished by the guidance of the Spanish artist Pierre Daura. By 1950, Twombly found himself studying in New York, where he would meet artists Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns; the trio would forge a deep, lifelong friendship, influencing each other’s artistic practices. (In serendipitous symmetry, Rauschenberg is also the current subject of a major retrospective at Tate Modern in London).

‘Blooming’, 2001–2008.

The show opens with a painting exhibited at Twombly’s first solo exhibition at Stable Gallery in New York in 1955. It’s a work that the artist kept all his life, ‘unique’ in its semi-figurative nature. Among the graffiti-like scrawls, an eye stares down visitors at the entrance. As curator Jonas Storsve explains, ‘The visitor watches the painting, at the same time the painting looks back.’

It’s a sentiment that carries throughout the show. Personal anecdotes of love, sex and death pervade Twombly’s works, but the cryptic artist always deftly deflects, citing various real-world events or Greco-Roman influences.

The retrospective closes with works produced at the end of Twombly’s career, in his studio in Gaeta. © Centre Pompidou.

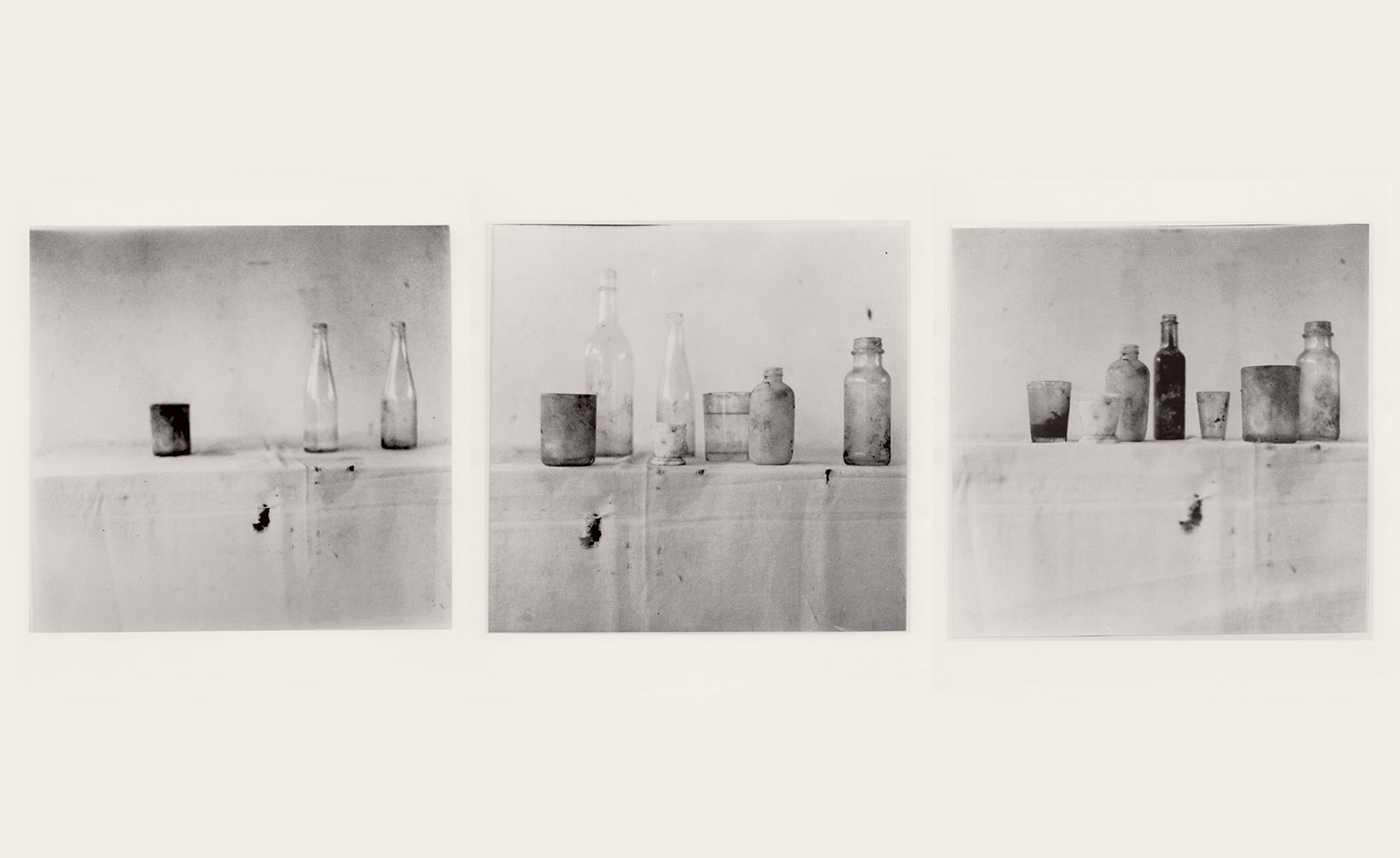

Twombly’s artistic transformation is explored in earnest at the Centre Pompidou. Along the way, visitors also get a glimpse into other lesser-known facets of his practice – an array of his sculptures perfectly punctuate the exhibition halfway through, while his Polaroids are a revelation. (The enigmatic Twombly photographed quite extensively throughout his career, but only first revealed these images in the 1990s.)

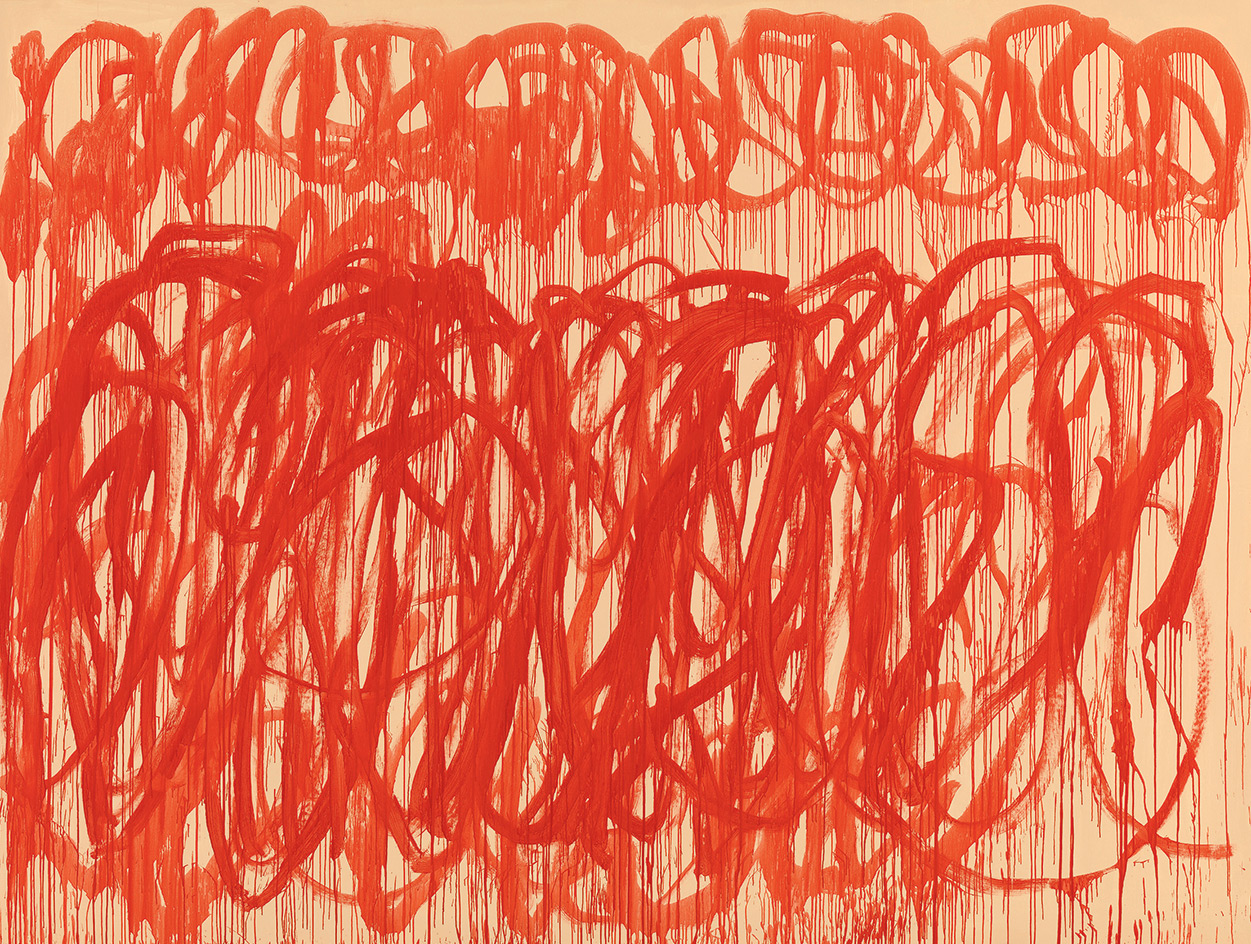

In 2005, at the height of the Iraq War, Twombly embarked on an epic series of paintings in his Gaeta studio. Returning to the characteristic writing he had explored in the Black Paintings of the late 1960s, the Bacchus series serves as the show-stopping finale; potent, swirling canvases of blood-red paint allude to wine and death at once. Twombly’s evolution is complete.

‘Sans titre (A Gathering of Time)’, 2003.

The Centre Pompidou retrospective – comprehensive, but arguably incomplete – does an immense service to Twombly’s oeuvre, unfurling the complexities of an artist oft maligned in his time, but certainly not now.

The major survey spans Twombly’s 60-year career through some 140 paintings, drawings, photographs and sculptures mapped out chronologically. Pictured, Untitled (Lexington), 1951.

Still Life, Black Mountain College, 1951.

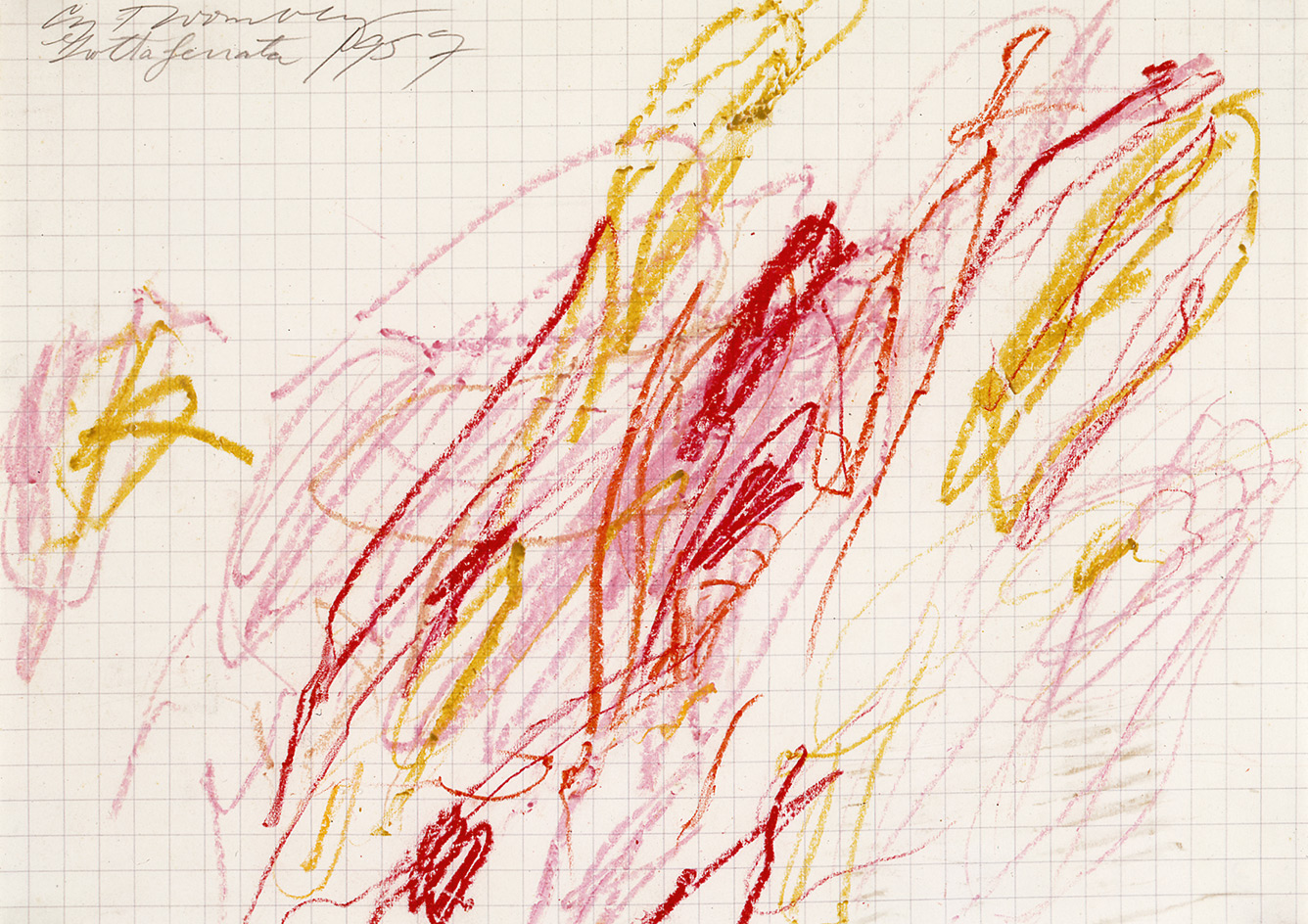

Untitled (Grottaferrata), 1957.

Sperlong Collage, 1959.

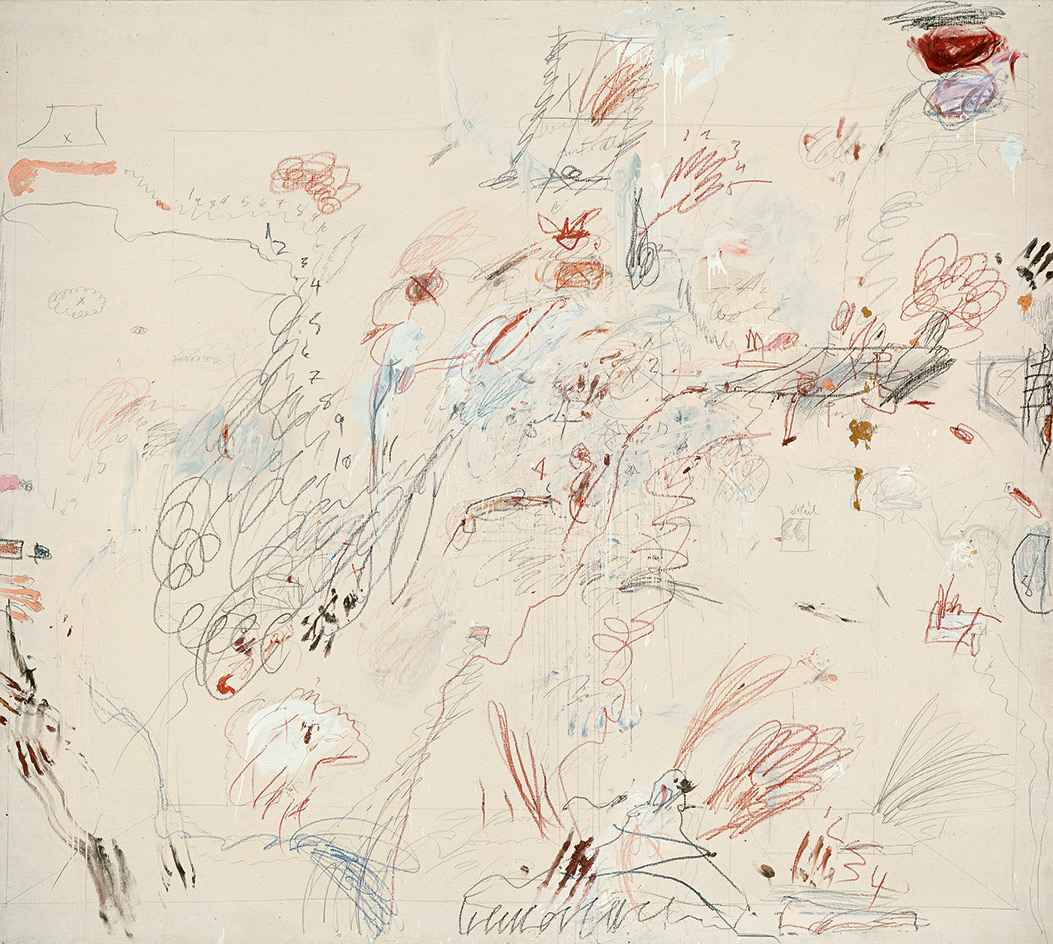

The fourth room of the exhibition is dedicated to works the artist produced in Rome between 1960 and 1962, following his marriage to Italian aristocrat Luisa Tatiana Franchetti. Twombly produced some of his most sexual paintings during this period. © Centre Pompidou.

Dutch Interior, 1962.

In late 1963, following John F Kennedy’s assassination, Twombly devoted a cycle of nine paintings to the Roman emperor Commodus (161–192), son of Marcus Aurelius and remembered as a cruel and bloodthirsty ruler

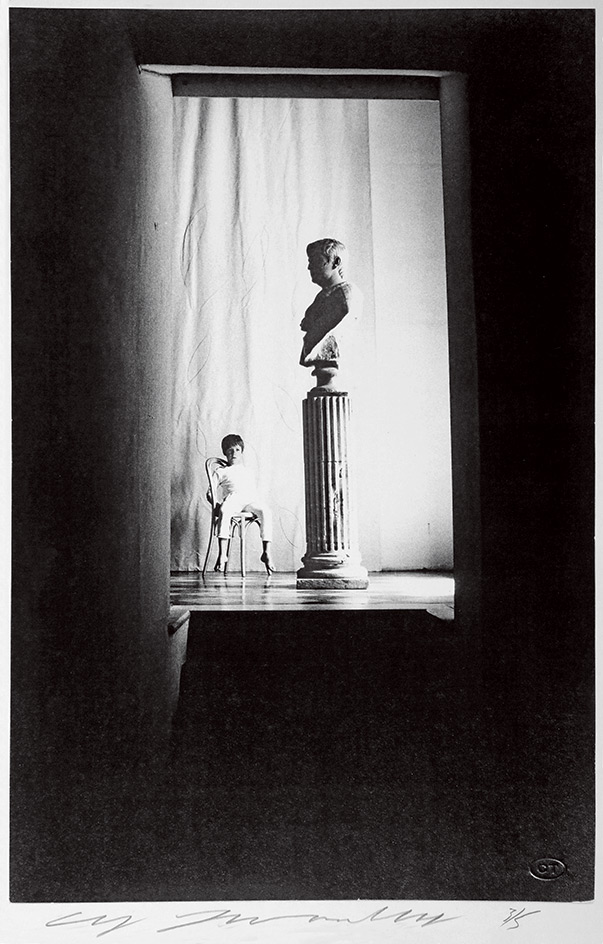

The Paris exhibition was organised with the support of the artist’s son, Alessandro Twombly – the show includes this 1965 portrait of him as a child.

Night Watch, 1966. , Inc; and Cheim & Read

Visitors also get a glimpse into other lesser-known facets of Twombly’s practice – an array of his sculptures perfectly punctuate the exhibition halfway through. © Centre Pompidou.

In 1975, Twombly bought a 16th-century house at Bassano in Teverina, north of Rome, establishing his summer studio there. Inspired by Homer’s Iliad, read in Alexander Pope’s 18th-century English translation, he embarked in 1977 on the major cycle Fifty Days at Iliam, the ten paintings in which were completed over two successive summers. © Centre Pompidou.

Fifty Days at Iliam Shades of Achilles, Patroclus and Hector, 1978.

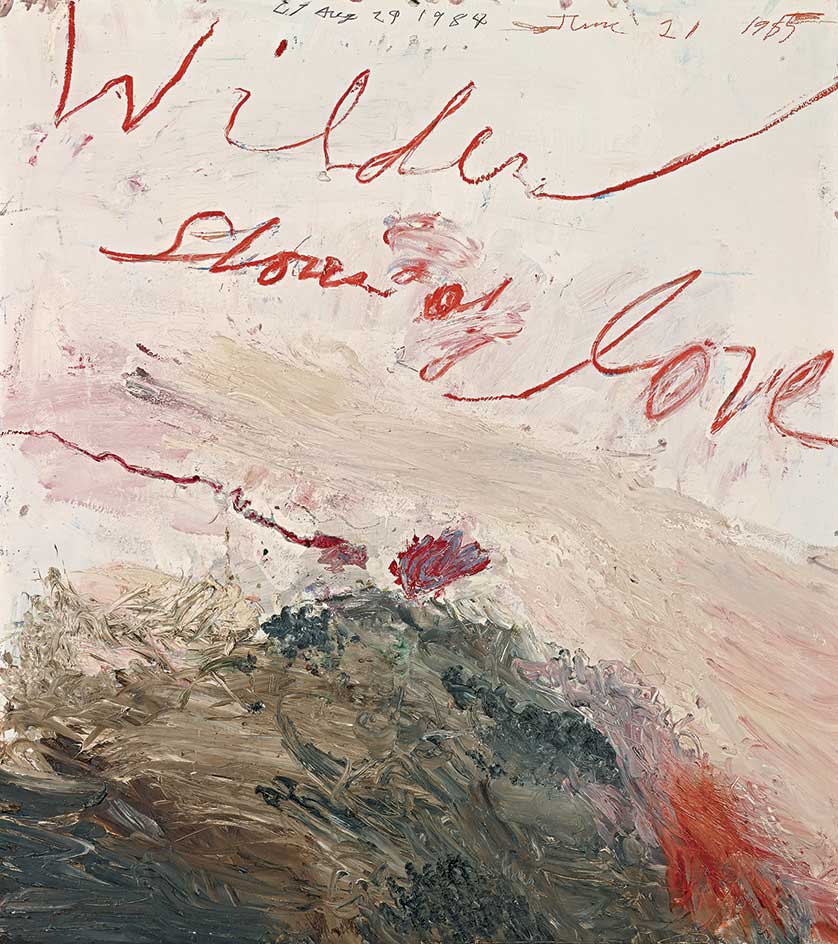

Wilder Shores of Love, 1985.

Summer Madness, 1990.

A selection of Twombly’s Polaroids are also on show as part of the survey.© Centre Pompidou

These images recall the work of the Italian painter Giorgio Morandi. Pictured, Lemons, 1998.

Coronation of Sesostris is one of the major painting cycles that punctuated Twombly’s career, differing from the purely abstract series in its incorporation of narrative elements. © Centre Pompidou.

The cycle is inspired by the god Râ, whose two sun-boats traversed the heavens both day and night. © Centre Pompidou.

For the Bacchus series, painted at Twombly’s Gaeta studio in early 2005, the artist again remembered Homer’s Iliad and returned to the writing he had explored in the Black Paintings of the late 1960s. Pictured, Untitled (Bacchus), 2005.

Here, he replaced the white wax crayon with red paint evocative of both blood and wine, allowed to run freely across the vast canvases. © Centre Pompidou.

INFORMATION

‘Cy Twombly’ is on view until 24 April. For more information, visit the Centre Pompidou website

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

ADDRESS

Centre Pompidou

Place Georges-Pompidou

75004 Paris

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss

-

‘David Hockney 25’: inside the artist’s blockbuster Paris show

‘David Hockney 25’: inside the artist’s blockbuster Paris show‘David Hockney 25’ has opened at Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris. Wallpaper’s Hannah Silver took a tour of the colossal, colourful show

By Hannah Silver

-

Jack White's Third Man Records opens a Paris pop-up

Jack White's Third Man Records opens a Paris pop-upJack White's immaculately-branded record store will set up shop in the 9th arrondissement this weekend

By Charlotte Gunn

-

‘The Black woman endures a gravity unlike any other’: Pharrell Williams explores diverse interpretations of femininity in Paris

‘The Black woman endures a gravity unlike any other’: Pharrell Williams explores diverse interpretations of femininity in ParisPharrell Williams returns to Perrotin gallery in Paris with a new group show which serves as an homage to Black women

By Amy Serafin

-

Tasneem Sarkez's heady mix of kitsch, Arabic and Americana hits London

Tasneem Sarkez's heady mix of kitsch, Arabic and Americana hits LondonArtist Tasneem Sarkez draws on an eclectic range of references for her debut solo show, 'White-Knuckle' at Rose Easton

By Zoe Whitfield

-

What makes fashion and art such good bedfellows?

What makes fashion and art such good bedfellows?There has always been a symbiosis between fashion and the art world. Here, we look at what makes the relationship such a successful one

By Amah-Rose Abrams

-

Alice Neel’s portraits celebrating the queer world are exhibited in London

Alice Neel’s portraits celebrating the queer world are exhibited in London‘At Home: Alice Neel in the Queer World’, curated by Hilton Als, opens at Victoria Miro, London

By Hannah Silver

-

‘You have to face death to feel alive’: Dark fairytales come to life in London exhibition

‘You have to face death to feel alive’: Dark fairytales come to life in London exhibitionDaniel Malarkey, the curator of ‘Last Night I Dreamt of Manderley’ at London’s Alison Jacques gallery, celebrates the fantastical

By Phin Jennings

-

Inside the distorted world of artist George Rouy

Inside the distorted world of artist George RouyFrequently drawing comparisons with Francis Bacon, painter George Rouy is gaining peer points for his use of classic techniques to distort the human form

By Hannah Silver