Exhibition review: Damien Hirst’s greatest hits in formaldehyde

‘Natural History’ at Gagosian Britannia Street, London is the first-ever show dedicated to Damien Hirst’s iconic formaldehyde sculptures. Chopped-up sharks, flayed innards, six-limbed cows – why do we keep returning for another slice?

We don’t do star-rated exhibition reviews at Wallpaper*. But if we did, we might need to break Damien Hirst’s ‘Natural History’ down a bit.

For ‘shock factor’, it might get a two; this is hardly Hirst’s formaldehyde foray. The show features one recent work, School Daze (2021), a rotating, multipart mobile of individually-pickled fish. It’s a more subtle intervention than the sliced and diced carcasses that surround it, but top marks for the pun.

More shocking perhaps was Hirst’s recent flurry of Cherry Blossom paintings, mainly due to their distinct lack of shock factor. ‘Natural History’, spanning 30 years of Hirst’s greatest hits in preservation, is a reminder of why the YBA icon pricked our ears up in the first place. This is prime-cut Hirst: unflinching and notorious.

Damien Hirst: ’Natural History’, installation view, 2022

We pity Cain and Abel (1994), who form the welcome party to this show: two black-and-white calves whose youthful buoyancy has been frozen in blue-tinged fluid since Blur released Parklife. Alive, but definitely not living.

Further in, This Little Piggy Went to Market, This Little Piggy Stayed at Home (1996) is another sorry, albeit anatomically fascinating sight. You might remember the nursery rhyme, you might not remember the part where the piggy was chopped in half.

Through saggy-eyed sharks, bowel-like sausages, flayed innards, six-limbed cows, miscellaneous fish, upside-down sheep and Hunterian Museum-esque jarred organs, we find the most startling diorama of all: The Beheading of John the Baptist (2006). It’s not the candy-coloured knives that get you. It’s not even the decapitated cow head perched on the butcher’s block or the clinical, white-tiled floor on which the rest of its body is strewn. It’s a clock that looms above the execution scene in suspended reality. Time of death: 11:53.

Damien Hirst, The Beheading of John the Baptist, 2006, Glass, painted stainless steel, silicone, ceramic floor tiles, stainless steel, resin butcher’s block, knives, machete, chain mail glove, cow, and formaldehyde solution.

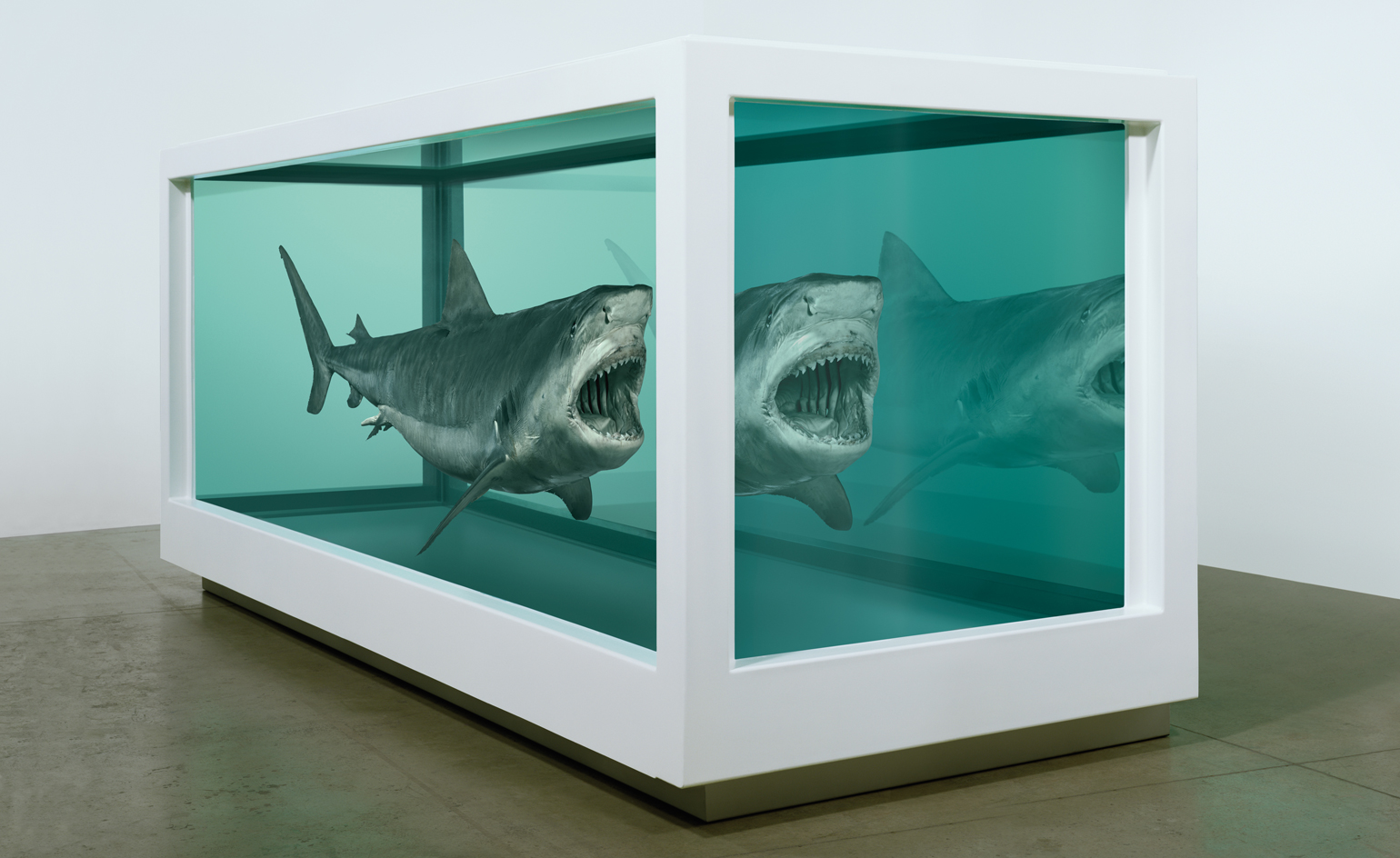

For ‘vegan friendliness’, the show would get a one (unless of course, a no-star option is available). It’s been 31 years since Hirst first dropped jaws with his fourteen-foot, formaldehyde tank-preserved tiger shark. Though veganism was a more fringe affair in 1991, it’s an unavoidable fact of death that for Hirst’s art to live, animals have died, and many people were, and remain, pretty unhappy about it.

Lest we forget the 2010 interview in which musician and animal-rights fanatic Morrissey told the artist Linder that Hirst’s ‘head should be kept in a bag’ for his treatment of animals. Or in 2017, when Hirst’s Venice exhibition was ambushed with manure by an animal rights group, and the many bouts of explosive disdain for his various butterfly massacres. But the use of dead animals in art was hardly invented by Hirst (one need look no further than hog-hair brushes, mashed-insect pigments or bone char paint). The difference here, one could argue, is the stark honesty.

Damien Hirst, The Ascension, 2003. Glass, painted stainless steel, silicone, acrylic, monofilament, calf, and formaldehyde solution.

For ‘timeliness’, it might get a four (and stay with me here). Admittedly, most people have seen one of these carcass-filled tanks before, or at least an image of one. But never in the history of art has London witnessed simultaneous survey shows by Damien Hirst, Francis Bacon and Louise Bourgeois. The city air is pulsating with pungent, visceral animalism, and it’s stifling. Like it or loathe it, flayed, deformed, dissected, crucified bodies (or parts of them) seem to be de rigueur-(mortis), and Hirst’s show plays a leading role.

But why do we keep coming back for another slice? Perhaps Hirst’s formaldehyde sculptures – grotesque as they are poetic – scratch the insatiable human itch for death and mortality. Maybe it’s a comfort to cling onto something as certain as death and tax(idermy).

A lot has changed since Hirst’s first pickle; life was simpler. Now, in a frenzy of pixel domination, immortal meta-selves, technology-powered monotony, and NFT art dropping (to new lows), maybe what we need is a bit of realism to feel alive, even if it is dead, and marinating in a tank.

Damien Hirst: Natural History, installation view, 2022.

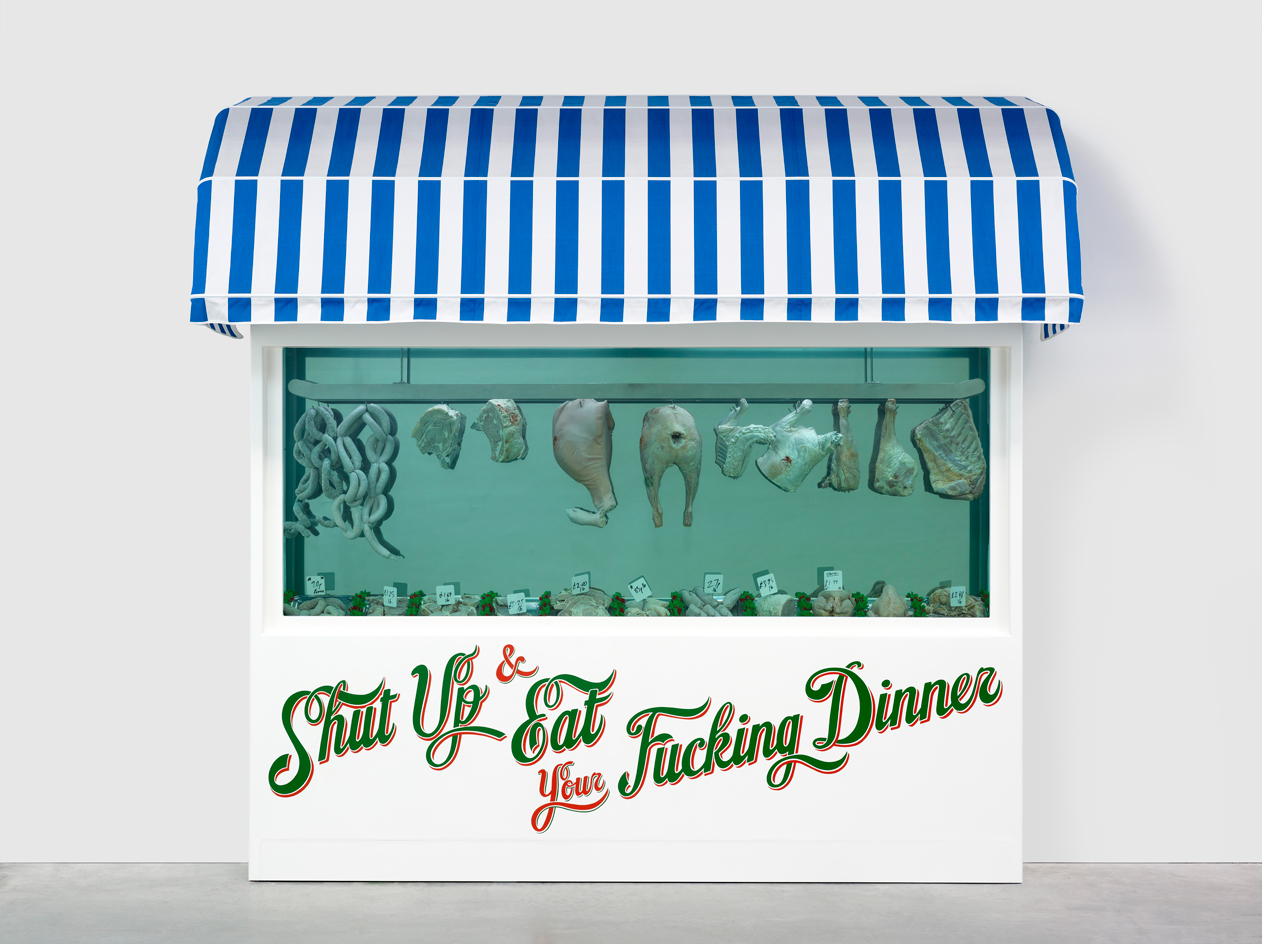

The Pursuit of Oblivion, 2004, Glass, painted stainless steel, silicone, stainless steel butcher’s rack and meat hooks, knives, sharpening steels, cleavers, saws, stainless steel chain, umbrella, resin hat, cloak, bird cage, resin books, resin armchair, resin walking cane, resin shoes, motorcycle helmet, sides of beef, sausages, dove and formaldehyde solution.

Damien Hirst, Schizophrenogenesis, 2008, Glass, painted stainless steel, silicone, acrylic, cows’ heads, and formaldehyde solution.

Damien Hirst, School Daze, 2021, Stainless steel, acrylic, electric motor, fish, and formaldehyde solution.

Damien Hirst, Shut Up and Eat Your Fucking Dinner, 1997, Steel, glass, formaldehyde, awning and meat products.

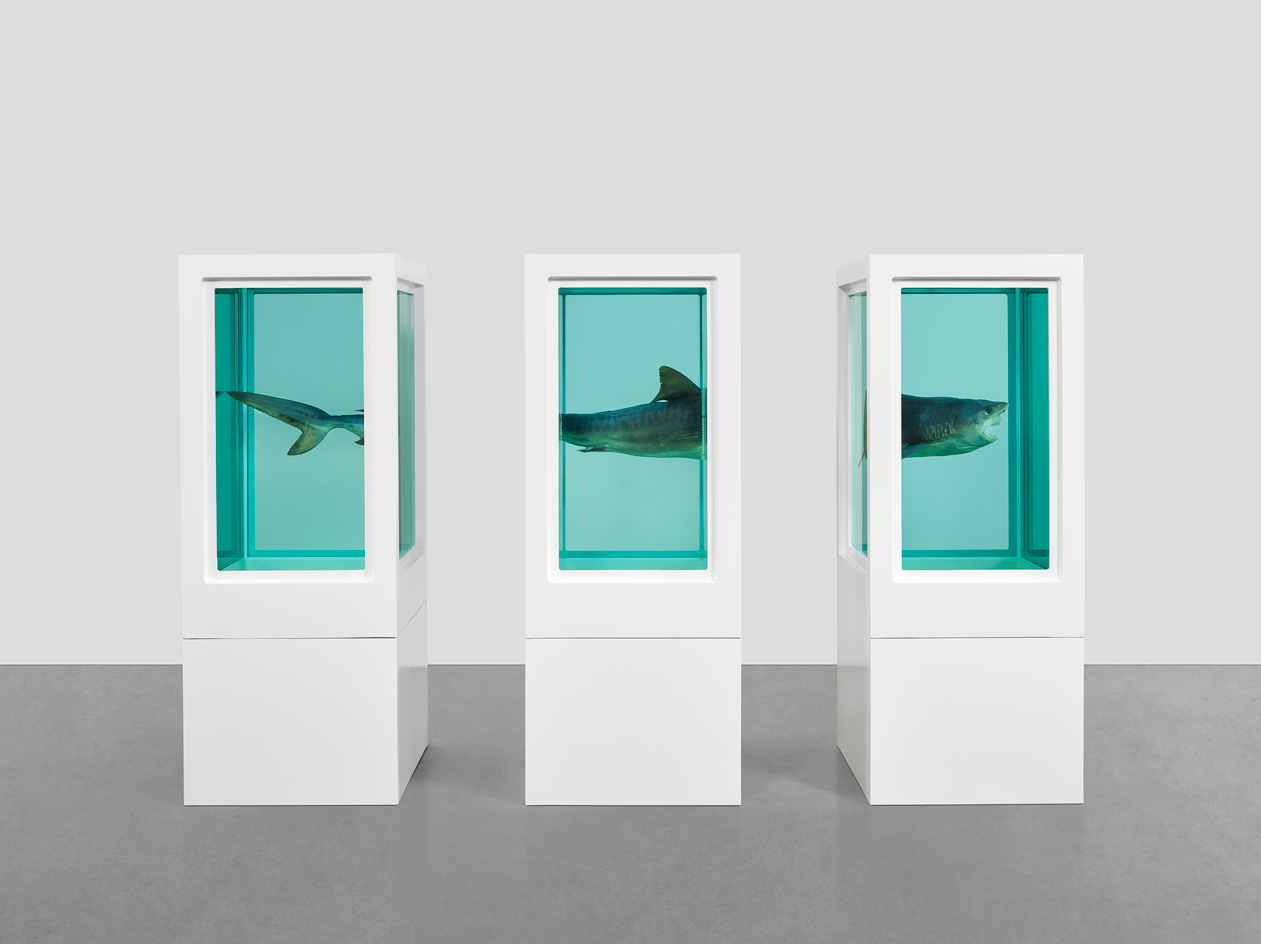

Damien Hirst, Myth Explored, Explained, Exploded, 1993, Glass, painted steel, silicone, monofilament, acrylic, shark, and formaldehyde solution, Triptych.

INFORMATION

Damien Hirst, ’Natural History’ is open from 10 March 2022 at Gagosian Britannia Street. gagosian.com

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Harriet Lloyd-Smith was the Arts Editor of Wallpaper*, responsible for the art pages across digital and print, including profiles, exhibition reviews, and contemporary art collaborations. She started at Wallpaper* in 2017 and has written for leading contemporary art publications, auction houses and arts charities, and lectured on review writing and art journalism. When she’s not writing about art, she’s making her own.

-

A Xingfa cement factory’s reimagining breathes new life into an abandoned industrial site

A Xingfa cement factory’s reimagining breathes new life into an abandoned industrial siteWe tour the Xingfa cement factory in China, where a redesign by landscape specialist SWA Group completely transforms an old industrial site into a lush park

By Daven Wu

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

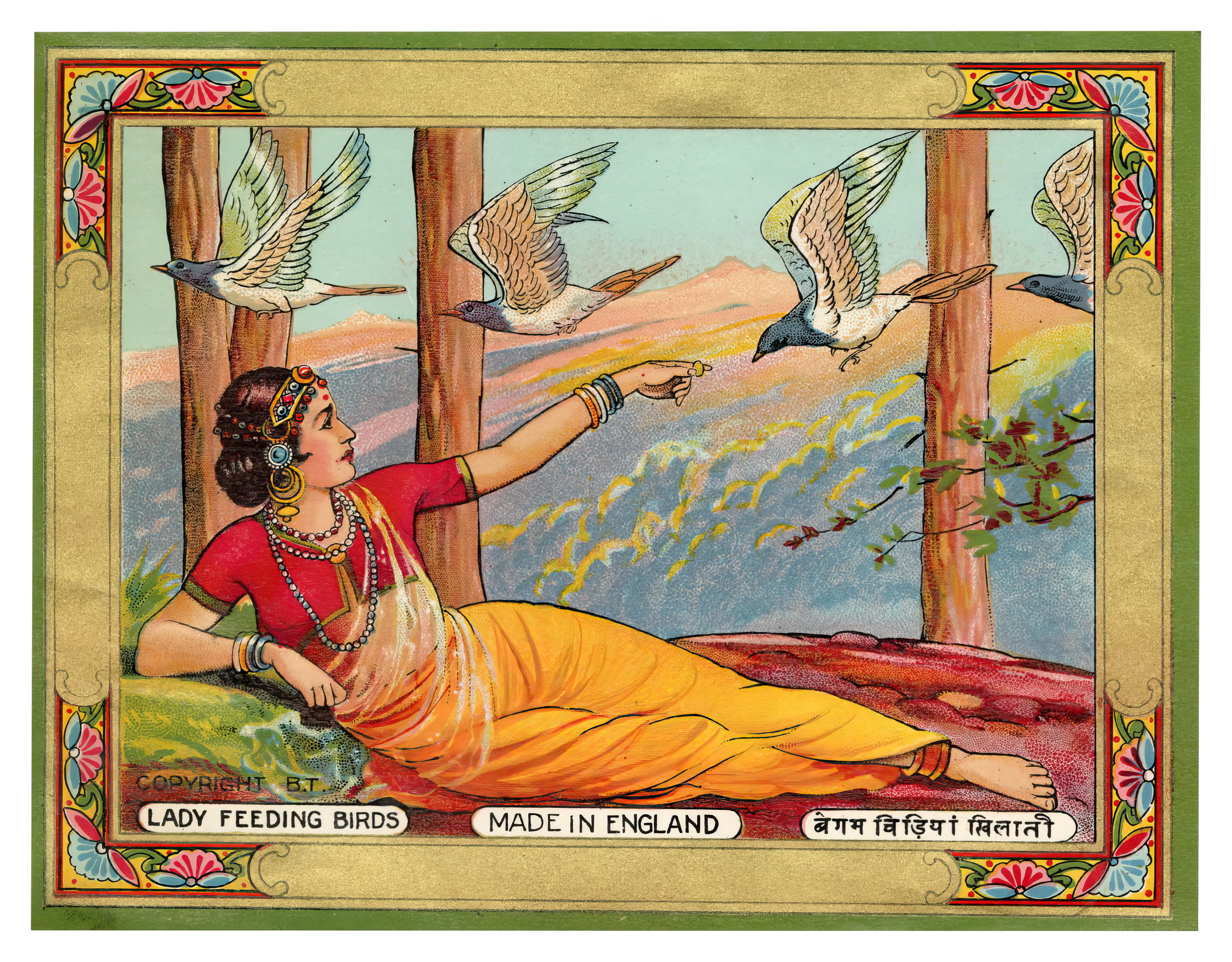

The art of the textile label: how British mill-made cloth sold itself to Indian buyers

The art of the textile label: how British mill-made cloth sold itself to Indian buyersAn exhibition of Indo-British textile labels at the Museum of Art & Photography (MAP) in Bengaluru is a journey through colonial desire and the design of mass persuasion

By Aastha D

-

Artist Qualeasha Wood explores the digital glitch to weave stories of the Black female experience

Artist Qualeasha Wood explores the digital glitch to weave stories of the Black female experienceIn ‘Malware’, her new London exhibition at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, the American artist’s tapestries, tuftings and videos delve into the world of internet malfunction

By Hannah Silver

-

Ed Atkins confronts death at Tate Britain

Ed Atkins confronts death at Tate BritainIn his new London exhibition, the artist prods at the limits of existence through digital and physical works, including a film starring Toby Jones

By Emily Steer

-

Tom Wesselmann’s 'Up Close' and the anatomy of desire

Tom Wesselmann’s 'Up Close' and the anatomy of desireIn a new exhibition currently on show at Almine Rech in London, Tom Wesselmann challenges the limits of figurative painting

By Sam Moore

-

A major Frida Kahlo exhibition is coming to the Tate Modern next year

A major Frida Kahlo exhibition is coming to the Tate Modern next yearTate’s 2026 programme includes 'Frida: The Making of an Icon', which will trace the professional and personal life of countercultural figurehead Frida Kahlo

By Anna Solomon

-

A portrait of the artist: Sotheby’s puts Grayson Perry in the spotlight

A portrait of the artist: Sotheby’s puts Grayson Perry in the spotlightFor more than a decade, photographer Richard Ansett has made Grayson Perry his muse. Now Sotheby’s is staging a selling exhibition of their work

By Hannah Silver

-

From counter-culture to Northern Soul, these photos chart an intimate history of working-class Britain

From counter-culture to Northern Soul, these photos chart an intimate history of working-class Britain‘After the End of History: British Working Class Photography 1989 – 2024’ is at Edinburgh gallery Stills

By Tianna Williams

-

Celia Paul's colony of ghostly apparitions haunts Victoria Miro

Celia Paul's colony of ghostly apparitions haunts Victoria MiroEerie and elegiac new London exhibition ‘Celia Paul: Colony of Ghosts’ is on show at Victoria Miro until 17 April

By Hannah Hutchings-Georgiou