Meet the artists integrating themselves into their work at Pinault Collection

The front gallery at Venice’s Punta della Dogana used to house a double-sabre wielding warrior ferociously perched on the shoulders of a roaring bear. Cast in bronze and encrusted in coral, the sculpture – standing more than 7m high – was a raucous overture to Damien Hirst’s flamboyant solo exhibition, ‘Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable’. Fast forward by one year, a gently shimmering curtain of blood red glass beads by Félix González-Torres stands in its place. On one side, Urs Fischer’s wax statue of a slightly hunchbacked man slowly melts as the candles on his head flicker away. This year’s show, ‘Dancing with Myself’, trades Hirst’s bombast for an altogether more introspective tone, but proves just as alluring as its predecessor.

Named after Billy Idol’s 1980 pop hit, the exhibition explores the ways in which artists have integrated their bodies, images and personas into photography, video and sculpture from the 1970s to the present day – ‘self-representation’, as curators Martin Bethenod (managing director of the Pinault Collection) and Florian Ebner (chief curator of photography at the Centre Pompidou) call it. Self-representation, as Bethenod is careful to point out, is distinct from self-portrait. ‘The artist’s body is not so much the subject of their work as the instrument with which they can approach a number of themes and stances, often political ones dealing with social or racial issues, and questions of identity, gender and sexuality’, he says.

A still from Lili Reynaud-Dewar’s I Am Intact and I Don’t Care (Pierre Huyghe, Centre Pompidou), 2013.

Opening with Fischer and González-Torres (a smaller piece by the latter, tracing the decline of T-cells in the blood of an AIDS’ patient, appears near the curtain), ‘Dancing with Myself’ suggests a sense of intimacy that at a glance, seems at odds with the monumental Tadao Ando-designed venue. But it succeeds in prompting a pensive silence as viewers then ascend the stairs into rooms filled with an impressive roster of modern and contemporary works – the photography of Lee Friedlander, Cindy Sherman and Roni Horn; the videos of Adel Abdessemend and Lili Reynaud-Dewar; and sculptures by Robert Gober, Alina Szapocznikow and Maurizio Cattelan, to name a few.

Being a collaboration between the Pinault Collection and Essen’s Museum Folkwang (where Ebner was chief curator of photography until 2017), ‘Dancing with Myself’ deftly combines works from both institutions. This allows panoramic perspectives on some artist’s careers – Sherman, for example, is represented by film stills from the Folkwang alongside four decades’ worth of photos from the Pinault Collection. But it’s the new dialogues among artists of different generations that leave the strongest impression.

The Folkwang lent a haunting Nan Goldin image, which shows the artist emerging from a toxic relationship with a bloodied eye and bruised face, yet a brave expression. Within the show, this shares a room with photographs from LaToya Ruby Frazier’s The Notion of Family series, from the Pinault Collection. Three decades younger than Goldin, Frazier approaches the camera with the same bracing honesty, but also brings together three generations of immediate and extended family in her hometown of Braddock, Pennsylvania, telling a story of defiance, grace and even optimism amid industrial decline and encroaching poverty.

Untitled #578, 2016, by Cindy Sherman.

Elsewhere, a trio of Lee Friedlander’s self portraits, documenting a journey through the East Coast in the 1960s joins contemporary photographs by the peripatetic Brazilian Paulo Nazareth. Titled Noticas de America, the series was shot as he made his way through South, and then North America on foot, visiting indigenous peoples and occasionally bearing handwritten signs that speak to their experiences of marginalisation and alienation. ‘Vendo mi imagen de hombre exótico’ (I sell the image of an exotic man), reads one. ‘I am an American also,’ says another, hoisted in front of a line of armoured police in what is ostensibly the United States.

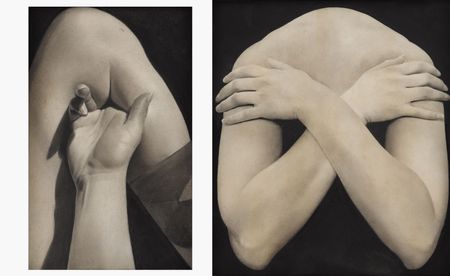

Another room juxtaposes disembodied body parts from a range of authors. Among others, There’s a single leg by Robert Gober, jutting out of a wall with a square patch removed from its black trouser to accommodate an unlit candle; an upside-down video by Bruce Nauman, zoomed in to the artist’s lips as he repeats the title, Lip Sync; close-ups of John Coplans’ palm, buttocks and heel, taken as he approached his eighth decade to challenge the convention of hiding aging bodies; a lamp sculpture by Szapocznikow, with a curious resemblance to puckered lips and an outstretched tongue. Of the latter, Bethenod says, ‘it has a feminine presence that looks sweet and delicate and erotic. But in fact it might be the most violent work, because her body was suffering as she battled with cancer.’

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

The show is not without its confrontational moments – the works of Gilbert & George occupy a central hall, including a large-scale picture, Blood Tears Spunk Piss, which alternates between microscopic imagery of bodily fluids and the two artists in the nude. In the final gallery is Steve McQueen’s video work, Cold Breath, a cinematic projection of the artist fondling his own nipple for ten minutes straight; an expression of racial and political themes for sure, but fundamentally an erotic statement. And while the exhibition excels in its more cerebral aspects, its raw physicality is also not to be overlooked.

Blood Tears Spunk Piss, 1996, by Gilbert & George.

Lampe IX, 1970, by Alina Zsapocznikow. Photo Paris, F Gousset

Haverstraw, New York, 1966, by Lee Friedlander

Self Portrait (Lupus Attack), 2005, by LaToya Ruby Frazier, from the series The Notion of Family.

INFORMATION

‘Dancing with Myself’ is on view until 16 December. For more information, visit the Pinault Collection website

ADDRESS

Punta della Dogana

Campo San Samuele 3231

30124 Venice

TF Chan is a former editor of Wallpaper* (2020-23), where he was responsible for the monthly print magazine, planning, commissioning, editing and writing long-lead content across all pillars. He also played a leading role in multi-channel editorial franchises, such as Wallpaper’s annual Design Awards, Guest Editor takeovers and Next Generation series. He aims to create world-class, visually-driven content while championing diversity, international representation and social impact. TF joined Wallpaper* as an intern in January 2013, and served as its commissioning editor from 2017-20, winning a 30 under 30 New Talent Award from the Professional Publishers’ Association. Born and raised in Hong Kong, he holds an undergraduate degree in history from Princeton University.

-

Come as you are to see Kurt Cobain’s acoustic guitar on show in the UK for the first time

Come as you are to see Kurt Cobain’s acoustic guitar on show in the UK for the first timeKurt Cobain’s acoustic guitar goes on display at the Royal College of Music Museum in London as part of an exhibition exploring Nirvana’s MTV Unplugged performance

By Tianna Williams Published

-

Promemoria’s new furniture takes you from London to Lake Como, with love

Promemoria’s new furniture takes you from London to Lake Como, with loveAhead of its Milan Design Week 2025 debut, we try out Promemoria’s new furniture collection by David Collins Studio, at founder Romeo Sozzi’s Lake Como villa

By Laura May Todd Published

-

Fluid workspaces: is the era of prescriptive office design over?

Fluid workspaces: is the era of prescriptive office design over?We discuss evolving workspaces and track the shape-shifting interiors of the 21st century. If options are what we’re after in office design, it looks like we’ve got them

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

Unlike the gloriously grotesque imagery in his films, Yorgos Lanthimos’ photographs are quietly beautiful

Unlike the gloriously grotesque imagery in his films, Yorgos Lanthimos’ photographs are quietly beautifulAn exhibition at Webber Gallery in Los Angeles presents Yorgos Lanthimos’ photography

By Katie Tobin Published

-

Saskia Colwell’s playful drawings resemble marble sculptures

Saskia Colwell’s playful drawings resemble marble sculpturesSaskia Colwell draws on classical and modern references for ‘Skin on Skin’, her solo exhibition at Victoria Miro, Venice

By Millie Walton Published

-

‘Life is strange and life is funny’: a new film goes inside the world of Martin Parr

‘Life is strange and life is funny’: a new film goes inside the world of Martin Parr‘I Am Martin Parr’, directed by Lee Shulman, makes the much-loved photographer the subject

By Hannah Silver Published

-

The Chemical Brothers’ Tom Rowlands on creating an electronic score for historical drama, Mussolini

The Chemical Brothers’ Tom Rowlands on creating an electronic score for historical drama, MussoliniTom Rowlands has composed ‘The Way Violence Should Be’ for Sky’s eight-part, Italian-language Mussolini: Son of the Century

By Craig McLean Published

-

Meet Daniel Blumberg, the British indie rock veteran who created The Brutalist’s score

Meet Daniel Blumberg, the British indie rock veteran who created The Brutalist’s scoreOscar and BAFTA-winning Blumberg has created an epic score for Brady Corbet’s film The Brutalist.

By Craig McLean Published

-

Remembering David Lynch (1946-2025), filmmaking master and creative dark horse

Remembering David Lynch (1946-2025), filmmaking master and creative dark horseDavid Lynch has died aged 78. Craig McLean pays tribute, recalling the cult filmmaker, his works, musings and myriad interests, from music-making to coffee entrepreneurship

By Craig McLean Published

-

Remembering Oliviero Toscani, fashion photographer and author of provocative Benetton campaigns

Remembering Oliviero Toscani, fashion photographer and author of provocative Benetton campaignsBest known for the controversial adverts he shot for the Italian fashion brand, former art director Oliviero Toscani has died, aged 82

By Anna Solomon Published

-

Distracting decadence: how Silvio Berlusconi’s legacy shaped Italian TV

Distracting decadence: how Silvio Berlusconi’s legacy shaped Italian TVStefano De Luigi's monograph Televisiva examines how Berlusconi’s empire reshaped Italian TV, and subsequently infiltrated the premiership

By Zoe Whitfield Published