Working the room: Daniel Buren sheds light on his new installation

Daniel Buren – possibly France’s most adored living artist – knows the walls of Lisson Gallery very well. He’s been working with them since the 1970s. In 1976, he painted rows of violet and brown stripes onto the walls, for an audacious installation called ‘On two levels with two colours’, an attempt to subvert the usual gallery-going experience, and force the visitor to consider the purpose of the commercial gallery, as a social, economic and political space, and its implied neutrality.

Since that first exhibition, London has changed a lot. ‘So many things indeed. The city is even more cosmopolitan, busier, richer, more chaotic in term of traffic, and, funny enough, much more French!’ Buren muses. ‘Of course I cannot forget to mention how the physicality of the city itself changes. It’s absolutely amazing if you look at London from a high point, like the new Tate observatory, you realize how the “landscape” is transformed, and continues to be, with cranes everywhere and old famous buildings known as the landmarks of the old city disappearing – masked by huge new structures which seem to make these referential architectural monuments appear like mere models of an old time (as if they were ashamed of those monuments).’

Installation view of ‘PILE UP: High Reliefs. Situated Works’ at Lisson Gallery, London. © Daniel Buren. Courtesy of Lisson Gallery

The 79-year-old master of colourful conceptual art has often suggested that it’s what surrounds his works – the architecture, environments, and people who inhabit them – rather than the works themselves, that give them their power and presence. In 1965, he first introduced his 8.7cm wide, iconic vertical stripe, a size he has never deviated from, and since then, he has only worked site-specifically, and very often, and deliberately, with gallery spaces. In his Lisson exhibition in the 70s, Buren’s stripes encouraged the visitor to take a certain path around the galleries.

Unveiling his latest Lisson exhibition in London last week, ‘Pile Up: High Reliefs. Situated Works’, the stripes of his high reliefs serve a similar purpose: ‘These works imply to the spectator the necessity to walk from left to right (or the contrary) in doing a sort of semi-circle in front of it, or if you prefer, an angle of 180 degrees (at least he or she doesn’t want to see really how these pieces are working?) Like for most of my works, the movement of the spectator is necessary if he or she wants to really see the work. To stay just in front of it, is not and will not be enough.’

Installation view of ‘PILE UP: High Reliefs. Situated Works’ at Lisson Gallery, London. © Daniel Buren. Courtesy of Lisson Gallery

It’s clear that Buren’s approach hasn’t changed, but his work couldn’t feel any more contemporary, five decades on: it’s easy to see why artists who, like Buren in the 70s, work outdoors, (among them Maser, Camille Walala and Maya Hayuk) have been inspired by his approach to activating the meaning of different kinds of spaces, as much as by the aesthetic of his monochromatic stripes.

The new, distinctly architectural structures – perhaps in part a reference to the physicality of London’s shape-shifting urban landscape – go up the walls, and we travel with them: triangular aluminium prisms, painted in brilliant reds, blues, yellows, poke out, while mirror-finished panels draw you in. This action itself makes you think about the place of art now and the way we engage with it. Buren’s works do not try to change Lisson’s walls, but they can make us feel differently within them – and about them.

Installation view of ‘PILE UP: High Reliefs. Situated Works’ at Lisson Gallery, London. © Daniel Buren. Courtesy of Lisson Gallery

For example, staring into one work, the green of the trees and the red brickwork are reflected back from outside the gallery – and seem to find themselves, somehow in the vibrant green and red of the protruding prisms. Elsewhere, it’s the edges of other works that come into view, or the sharp lines of the stairs and skylights, creating new patterns within themselves.

What keeps the artist motivated after so many years? ‘Take Picasso, Cézanne, Matisse or Titien, Michelangelo, Claude Monet, Joan Miró and so many more and you will see that they never stopped, and some of them even produced some of their most interesting and fresh works during their last years. I believe that any new work come from previous one and that every new work opens a new door,’ Buren says. ‘So, if you don’t stop working, your own curiosity is kept always in alert – you are anxious to see what’s happening behind the new door – and from one step to the next, you are working non-stop with any more work refreshing your appetite to see more, to know more, to do more. I guess all artists, able to work long and continuously, will have similar answers. Any new project is a hope for the future, and you are excited to see it done. Nothing, except death, can stop you to see such an exciting program!’

Buren is probably not as radical as he was in the 70s – but he certainly still knows how to work a room.

INFORMATION

‘Pile Up: High reliefs. Situated Works’ is on view until 11 November. For more information visit the Lisson Gallery website

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

ADDRESS

Lisson Gallery

67 Lisson Street

London NW1 5DA

Charlotte Jansen is a journalist and the author of two books on photography, Girl on Girl (2017) and Photography Now (2021). She is commissioning editor at Elephant magazine and has written on contemporary art and culture for The Guardian, the Financial Times, ELLE, the British Journal of Photography, Frieze and Artsy. Jansen is also presenter of Dior Talks podcast series, The Female Gaze.

-

Marylebone restaurant Nina turns up the volume on Italian dining

Marylebone restaurant Nina turns up the volume on Italian diningAt Nina, don’t expect a view of the Amalfi Coast. Do expect pasta, leopard print and industrial chic

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Tour the wonderful homes of ‘Casa Mexicana’, an ode to residential architecture in Mexico

Tour the wonderful homes of ‘Casa Mexicana’, an ode to residential architecture in Mexico‘Casa Mexicana’ is a new book celebrating the country’s residential architecture, highlighting its influence across the world

By Ellie Stathaki

-

Jonathan Anderson is heading to Dior Men

Jonathan Anderson is heading to Dior MenAfter months of speculation, it has been confirmed this morning that Jonathan Anderson, who left Loewe earlier this year, is the successor to Kim Jones at Dior Men

By Jack Moss

-

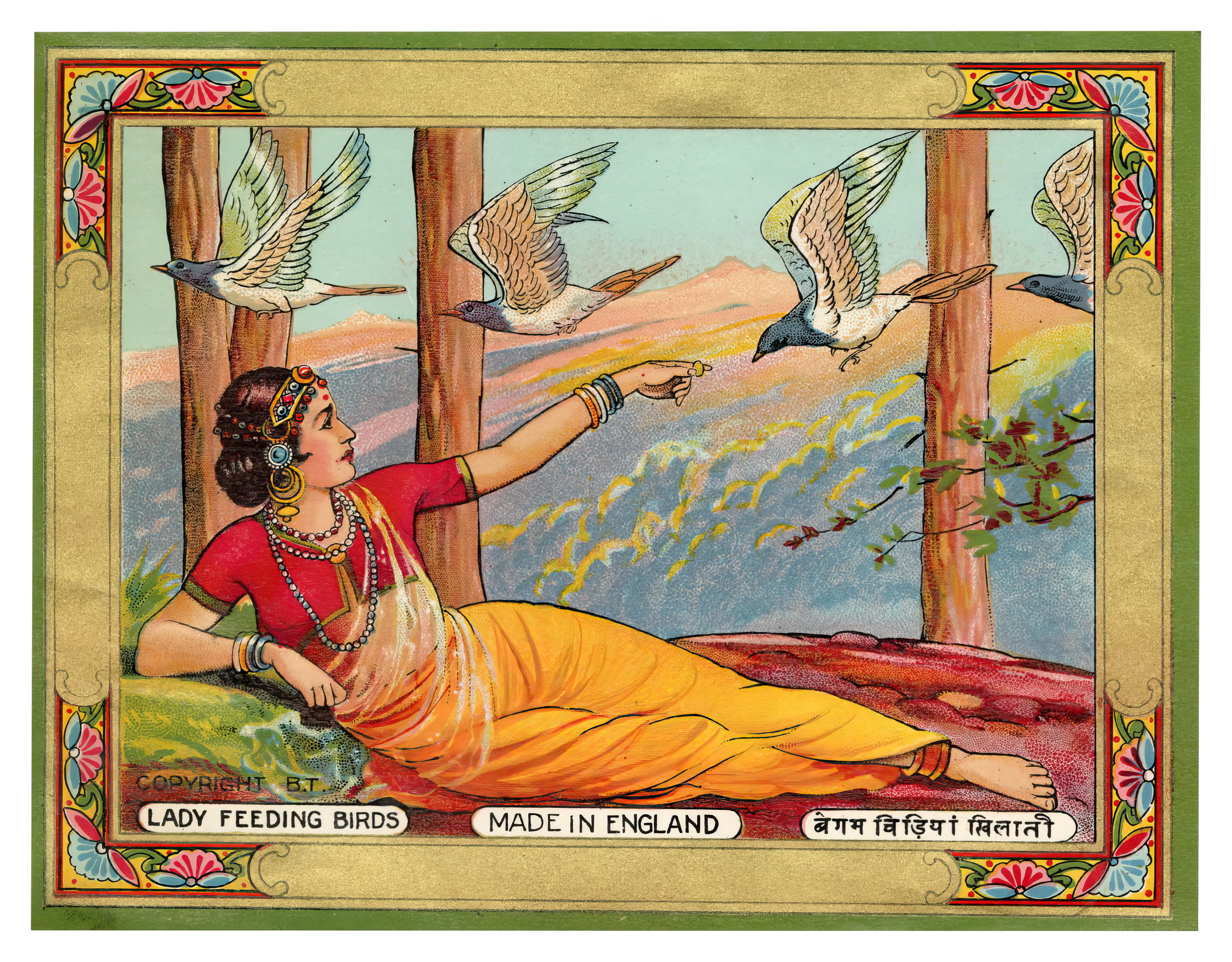

The art of the textile label: how British mill-made cloth sold itself to Indian buyers

The art of the textile label: how British mill-made cloth sold itself to Indian buyersAn exhibition of Indo-British textile labels at the Museum of Art & Photography (MAP) in Bengaluru is a journey through colonial desire and the design of mass persuasion

By Aastha D

-

Artist Qualeasha Wood explores the digital glitch to weave stories of the Black female experience

Artist Qualeasha Wood explores the digital glitch to weave stories of the Black female experienceIn ‘Malware’, her new London exhibition at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, the American artist’s tapestries, tuftings and videos delve into the world of internet malfunction

By Hannah Silver

-

Ed Atkins confronts death at Tate Britain

Ed Atkins confronts death at Tate BritainIn his new London exhibition, the artist prods at the limits of existence through digital and physical works, including a film starring Toby Jones

By Emily Steer

-

Tom Wesselmann’s 'Up Close' and the anatomy of desire

Tom Wesselmann’s 'Up Close' and the anatomy of desireIn a new exhibition currently on show at Almine Rech in London, Tom Wesselmann challenges the limits of figurative painting

By Sam Moore

-

A major Frida Kahlo exhibition is coming to the Tate Modern next year

A major Frida Kahlo exhibition is coming to the Tate Modern next yearTate’s 2026 programme includes 'Frida: The Making of an Icon', which will trace the professional and personal life of countercultural figurehead Frida Kahlo

By Anna Solomon

-

A portrait of the artist: Sotheby’s puts Grayson Perry in the spotlight

A portrait of the artist: Sotheby’s puts Grayson Perry in the spotlightFor more than a decade, photographer Richard Ansett has made Grayson Perry his muse. Now Sotheby’s is staging a selling exhibition of their work

By Hannah Silver

-

From counter-culture to Northern Soul, these photos chart an intimate history of working-class Britain

From counter-culture to Northern Soul, these photos chart an intimate history of working-class Britain‘After the End of History: British Working Class Photography 1989 – 2024’ is at Edinburgh gallery Stills

By Tianna Williams

-

Celia Paul's colony of ghostly apparitions haunts Victoria Miro

Celia Paul's colony of ghostly apparitions haunts Victoria MiroEerie and elegiac new London exhibition ‘Celia Paul: Colony of Ghosts’ is on show at Victoria Miro until 17 April

By Hannah Hutchings-Georgiou