Do Ho Suh creates the after-glow of time and place with fabric rooms and ritual rubbings

Last summer the Korean artist Do Ho Suh papered over much of the interior of a four-storey New York townhouse. It was thin paper, stuck down with gentle glue, a kind of second skin. Then he coated his fingers in pastel and rubbed the walls, ‘caressing them’ he says, different colours for different rooms. The rubbing got less intense the higher up the house he got and the rooms less familiar. Still, it’s a big house and it was a hot summer. Suh rubbed away his fingerprints. ‘I gave part of my body,’ he says.

Suh had moved into the basement of the house in Chelsea almost 20 years before, just after completing his MFA at Yale. It worked well as a small, 500 sq ft apartment and studio, or well enough given what Suh could afford. But it became more to him than affordable studio space. And leaving it, as he had to do, was a wrench, a sort of rupture that skinned him emotionally.

‘I was trying to hold onto something but it was also a ritual to let things go,’ he says. ‘Memories were triggered by the recovery of small textures or details that I had completely forgotten. Through the rubbing they resurfaced so I lived that time very intensively. And then I came out of it. It was like shedding skin and now I feel like I have been granted another body.’

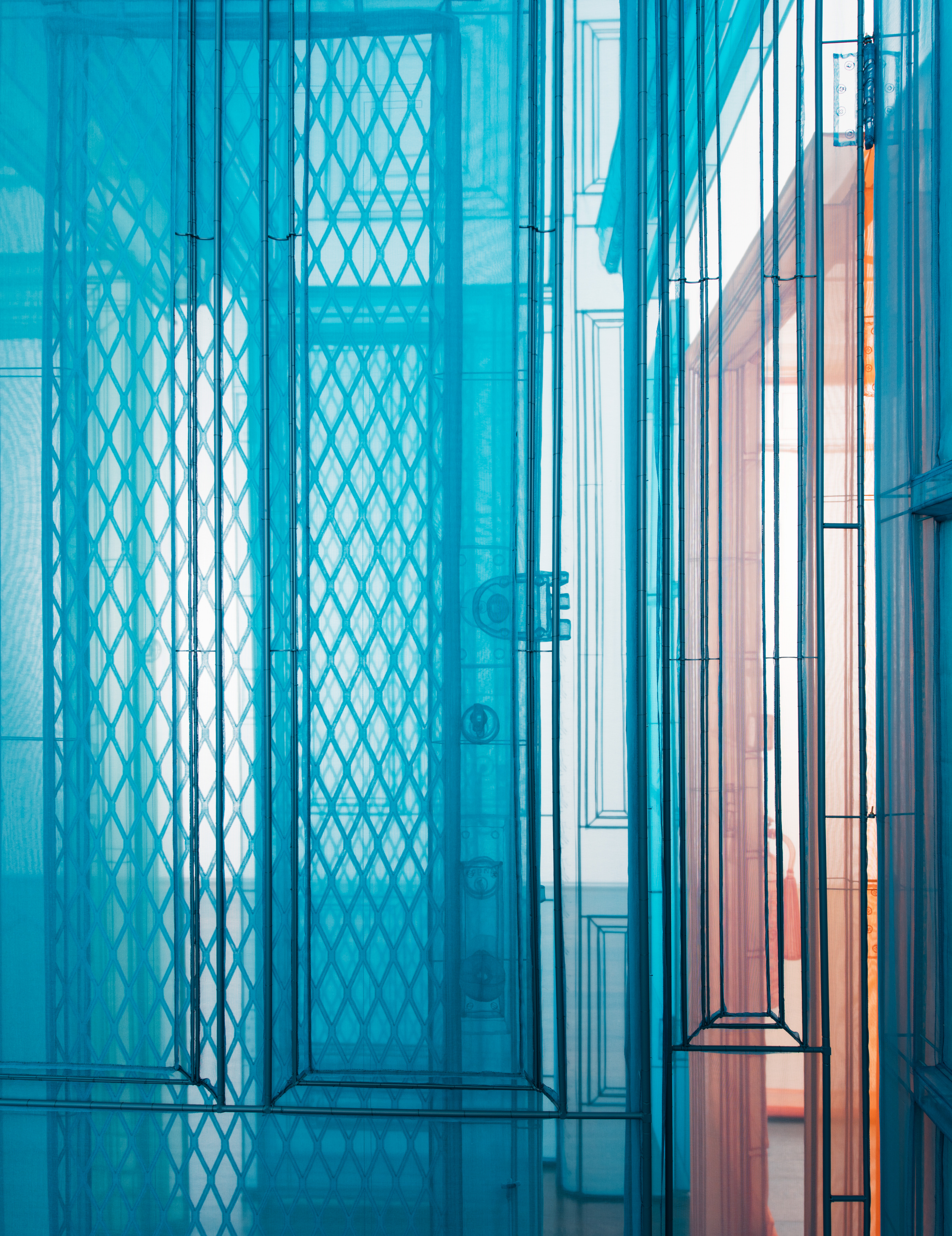

’Passage/s’ (detail), 2016.

The rubbings are now in a new studio Suh keeps in Greenpoint in Brooklyn, carefully numbered. They are precious to him. The house is being sold so he can’t go back and do it all again, even if he wanted to. His plan is to mount the rubbings on wooden panels and create a scale model of the house. The Rubbing/Loving Project, as he calls it, will be, you sense, the piece that defines this stage of his career (Suh is now 54). But it is more than that. ‘It became almost like a spiritual quest,’ he says. ‘It was not about my career, it was about commemorating my time there.’

The townhouse, once a dormitory for German sailors, was owned by psychotherapists Arthur and Doris ‘Dee’ Henoch. Dee had also been an actress and filmmaker and took an interest in Suh’s work. Arthur – who had served with actor Douglas Fairbanks Jr during World War II and not usually one for art – did too. After Dee died in 2005, Suh and Arthur became even closer. ‘He was very generous and supportive,’ says Suh. ‘We were very good friends for a very long time.’

Suh had arrived in the US in 1991 to study art at the Rhode Island School of Design. Though he spoke little English, he found the move liberating. Suh’s father, Suh Se-ok, is one of Korea’s best-known artists and Suh was relieved to be in a country that was unaware of his father’s reputation. But he also soon understood that the US’s relationship with its Korean immigrant population was complex to the point of hostility.

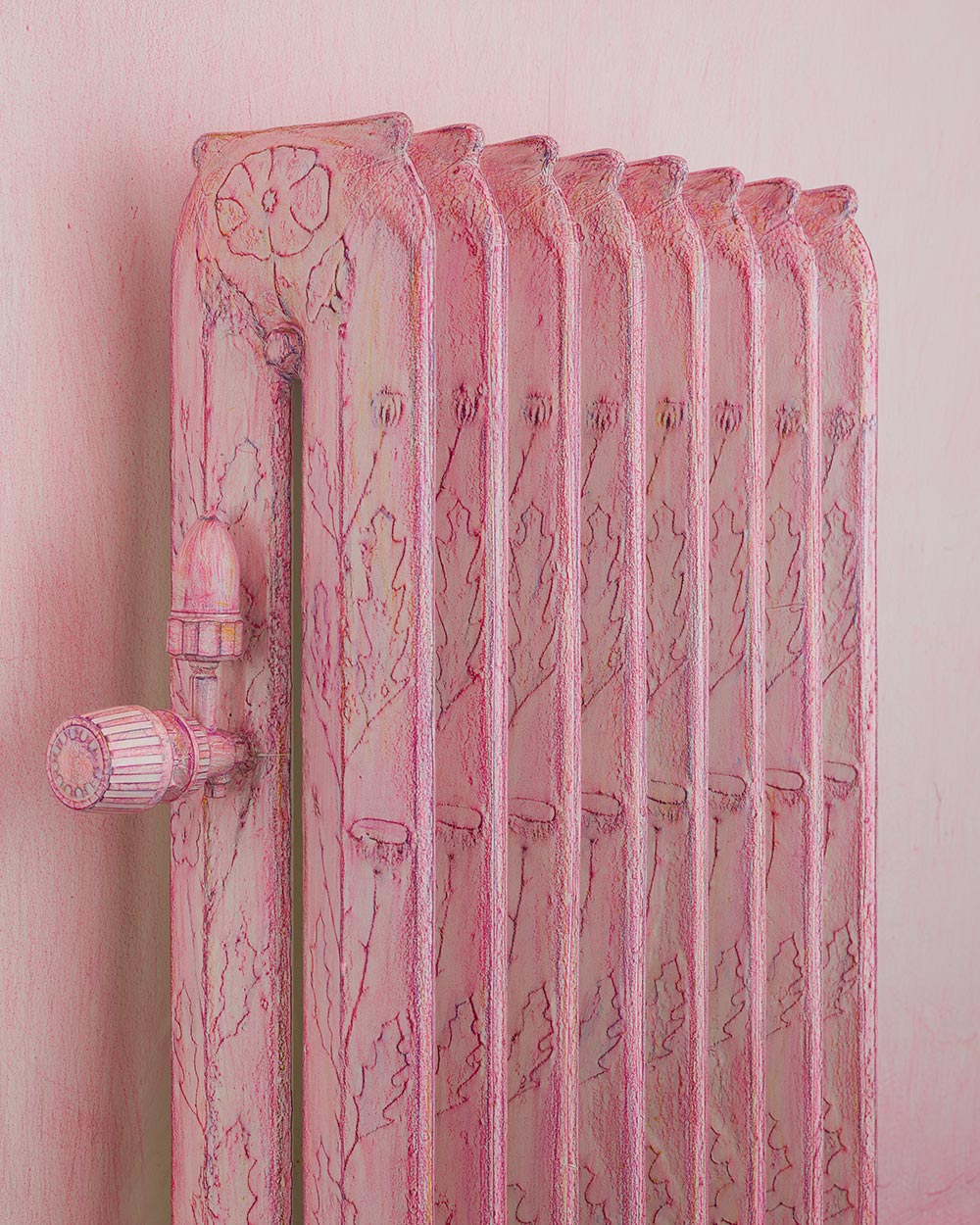

Suh’s apartment rubbed in yellow. The pink-rubbed door leads to the staircase and up to the townhouse.

While still at RISD, Suh created a jacket out of military dog-tags. He called it Metal Jacket and it identified Suh as an art star in the making. He refined the idea with 2001’s Some/One, creating a swooping, armoured robe, also out of dog-tags. He has made other pieces about the individual and the collective. In 2010’s Net-Work, he constructed what looked like a fishing net but was in fact a mesh of tiny human figures, arms and legs outstretched. He is not averse to high-impact showmanship. In 2012’s Fallen Star he perched a 30-ton house precariously on the roof of the Engineering School at the University of California in San Diego.

But perhaps his most haunting work is a series of stitched-together, fabric interior spaces, pop-coloured polyester apparitions, residues, perhaps, but of something essential. The first in the series were alien to most US viewers but only because they were the internal workings of a traditional Korean house, a hanok built by his father in the 1970s. But then, as Suh offered up fragile traces of his New York apartment – of radiators, sinks and toilets and the familiar fixtures of cheap rentals and first homes – they connected. People moved within them and understood how domestic spaces can have a sort of psychic stickiness, that repeated movements within spaces might leave something behind. Place and placelessness are what people talk about when they talk about Suh’s work. Suh admits that these pieces began simply as an attempt to make his place portable, even wearable, so he could take it with him wherever he went.

Suh had imagined that New York was his forever place, but in 2010 he moved to London to be with his new wife Rebecca Boyle Suh, who works in arts education. They had a daughter. And then another. But Suh kept the studio in New York, tied somehow to that place. Uprooting and re-rooting unsettled him because he realised that it might happen again. That it was possible, inevitable even, but painful.

Suh’s apartment rubbed in blue.

At a new show now on at the Victoria Miro gallery in London, Suh is presenting a series of ‘in-between’ spaces, nine fabric spectres of hallways and odd connecting places. ‘Hubs’ he calls them, from homes and studios in New York, Berlin, London and Seoul. At the end is a video screen running an animation Suh has made using hundreds of still images of corridors; an ‘infinite corridor’ he calls it, never really getting or going anywhere.

Suh’s home and studio is just around the corner from the Miro gallery, near the Regent’s Canal in Islington. It is an area of grand townhouses and the culturally curious, not unlike Chelsea. But Suh clearly struggles to feel comfortable here. It is not his forever place. ‘I always thought there should be some sort of end,’ he says. ‘A final destination. I thought that was New York but it turns out not. And I don’t feel that London is my final destination.’ The Miro show is about his time in London, he says, his place and placelessness, that sense of being in-between.

It is the ‘Hub’ pieces that feature on this month’s subscriber cover and in our fashion story, shot by Sofie Middernacht and Maarten Alexander. It is the first time Suh’s fabric architecture has been shot with live visitors, carefully styled as a colourful counterpoint in this case. Suh was an on-set collaborator during the shoot, again a new, and slightly unnerving, experience. ‘I knew I had to let go once I had agreed to do this but Sofie and Maarten were very respectful,’ he says. ‘I didn’t really say anything while they were shooting the fashion, and then we worked together on the cover. I’m used to a straightforward documentation of my work. But they had a very specific view. They played with the light and there is a human presence. It was interesting to see my work read in a different way.’

The Miro show also includes a three-screen film shot using GoPro cameras stuck to Suh’s daughter’s buggy. ‘My arrival in London coincided with the arrival of my daughter, so we explored this new environment together,’ he says. ‘Some of the films are in Korea and the interesting thing is that you don’t really notice the switch from city to city. Seoul blends with London.’

Do Ho Suh’s ’Rubbing/Loved Project’, 2015-16, coloured pencil on paper, photographed in situ at 348 West 2nd Street, New York

Suh also worked with the Singapore Tyler Print Institute on Specimen Series, large-scale cyanotypes of fabric objects that look like strange X-rays or spirit presences. A lightbulb from his New York apartment, among other things, appears in three forms: 3D fabric, 2D gelatin and cyanotype. ‘I think ultimately I am seeking something intangible, to see something that I cannot see, a sort of residue.’

In 2011, Arthur Henoch’s children warned Suh that their father was ill with Alzheimer’s. ‘He casually complained about loss of memory, just little things at the beginning,’ Suh says. ‘He started to forget where he had put the rent cheque I gave him so I had to reissue those several times. Finally he asked me to arrange an automatic payment.’

Suh knew he might have to give up the space and he looked for new ways to memorialise it, to mark his time there and what it had meant. He understood that the fabric pieces he had made of the apartment had their limits. ‘I always felt that there was a quality or elements missing.’ So he started to rub.

Arthur died in January last year, aged 90. His son Gary suggested that Suh keep rubbing, moving up the stairs and into the house; something Suh had wanted to do but was too polite to ask. It would be a memorial to his father and, Gary understood, a memorial to Suh’s relationship with him. But things got complicated. Arthur’s three children bounced between supporting the project and calling things off. They were keen to sell the house; a Chelsea townhouse is a considerable asset, and to have an artist rubbing and wrapping the place might get in the way of a quick deal. ‘I think my art tortured the children,’ Suh says. ‘They knew I was doing something they couldn’t do. And they completely understood the meaning of it. But the practicalities of selling the house meant they were torn.’ It was almost six months before Suh actually started work in the house.

Do Ho Suh’s ’Rubbing/Loved Project’, 2015-16, coloured pencil on paper, photographed in situ at 348 West 2nd Street, New York

In the meantime he started another rubbing of his apartment, his third time around. ‘It was different doing the rubbing after Arthur died,’ Suh says. ‘I knew now that I really had to move out. And I was more attentive. There have been so many lives in that house. You see a light switch that has probably been there since the 1930s. Time has accumulated on those objects. I think about how many times I flipped that switch. ‘I think when you first move in somewhere, you are more aware of the volume than the space itself. And then you forget about all that and it is about your routine inside that space. You wake up, you go to the bathroom, take a shower, flip the switches. And the movement is actually the memory of the space. The rubbings remind me of that movement.’

After that he moved on to a staircase from the apartment to the house, behind a door that was always locked. And then he moved up the house; but the higher he went, the less he rubbed. ‘The trace of loving gets weaker, and then you go into these blank spaces.’ The couple’s bedroom was off-limits, the children had said; it would be a void. And the office where Arthur and Dee saw their patients was wrapped but not rubbed. That room was for other people’s memories.

Suh finally completed the project last November. ‘When the rubbings were on the walls, it felt like a kind of illusion, but when they are removed, they become more opaque, more solid in a way. I think that when it is reconstructed, it will have a different life.’ Now he has to find somewhere to show the final piece, the complete house. He would like it to be in New York. It is, as he says, such a New York story. And the story is part of the project.

Even though the project is finished, he keeps working on his trace of Arthur’s house. ‘I love those cardboard houses that children have, that fold up. So it will be a grown-up version of that, really. It will have a metal frame and everything will be collapsible. The idea is quite simple. I want to move my house, to carry my house. It just takes a lot of effort to realise it.’

As originally featured in the March 2017 issue of Wallpaper* (W*216)

Passage/s (detail), 2016.

Passage/s (detail), 2016

Left, Staircase, Ground Floor, 348 West 22nd Street, New York, NY 10011, USA, 2016. Right, Main Entrance, 348 West 22nd Street, New York, NY 10011, USA, 2016

From left, Entrance, Ground Floor, 348 22nd Street, New York, 10011, USA, 2015; Entrance, Unit 2, 348 West 22nd Street, New York, NY 10011, USA, 2016; and Entrance, Unit G5, Union Wharf, 23 Wenlock road, London, N1 7SB, UK, 2016

INFORMATION

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

‘Passage/s’ is on view until 18 March. For more information, visit the Victoria Miro website

ADDRESS

Victoria Miro

16 Wharf Road

London N1 7RW

-

The Testament of Ann Lee brings the Shaker aesthetic to the big screen

The Testament of Ann Lee brings the Shaker aesthetic to the big screenDirected by Mona Fastvold and featuring Amanda Seyfried, The Testament of Ann Lee is a visual deep dive into Shaker culture

-

Dive into Buccellati's rich artistic heritage in Shanghai

Dive into Buccellati's rich artistic heritage in Shanghai'The Prince of Goldsmiths: Buccellati Rediscovering the Classics' exhibition takes visitors on an immersive journey through a fascinating history

-

Love jewellery? Now you can book a holiday to source rare gemstones

Love jewellery? Now you can book a holiday to source rare gemstonesHardy & Diamond, Gemstone Journeys debuts in Sri Lanka in April 2026, granting travellers access to the island’s artisanal gemstone mines, as well as the opportunity to source their perfect stone

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week'Tis the season for eating and drinking, and the Wallpaper* team embraced it wholeheartedly this week. Elsewhere: the best spot in Milan for clothing repairs and outdoor swimming in December

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekFar from slowing down for the festive season, the Wallpaper* team is in full swing, hopping from events to openings this week. Sometimes work can feel like play – and we also had time for some festive cocktails and cinematic releases

-

The Barbican is undergoing a huge revamp. Here’s what we know

The Barbican is undergoing a huge revamp. Here’s what we knowThe Barbican Centre is set to close in June 2028 for a year as part of a huge restoration plan to future-proof the brutalist Grade II-listed site

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekIt’s wet, windy and wintry and, this week, the Wallpaper* team craved moments of escape. We found it in memories of the Mediterranean, flavours of Mexico, and immersions in the worlds of music and art

-

Each mundane object tells a story at Pace’s tribute to the everyday

Each mundane object tells a story at Pace’s tribute to the everydayIn a group exhibition, ‘Monument to the Unimportant’, artists give the seemingly insignificant – from discarded clothes to weeds in cracks – a longer look

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekThis week, the Wallpaper* team had its finger on the pulse of architecture, interiors and fashion – while also scooping the latest on the Radiohead reunion and London’s buzziest pizza

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekIt’s been a week of escapism: daydreams of Ghana sparked by lively local projects, glimpses of Tokyo on nostalgic film rolls, and a charming foray into the heart of Christmas as the festive season kicks off in earnest

-

Wes Anderson at the Design Museum celebrates an obsessive attention to detail

Wes Anderson at the Design Museum celebrates an obsessive attention to detail‘Wes Anderson: The Archives’ pays tribute to the American film director’s career – expect props and puppets aplenty in this comprehensive London retrospective