Doug Aitken’s epic art finds a home in a transformed auto repair shop in California

As Doug Aitken features in the Wallpaper* 300, our guide to creative America, we revisit the surreal signage and sun-blasted landscapes of his portfolio of work, exclusively published in our November 2019 issue

Mark Mahaney - Photography

As Doug Aitken features in Wallpaper* USA 300 – a guide to creative America – we revisit our article from November 2019 Wallpaper*, and showcase the portfolio of work the artist shared exclusively for that issue.

Washington Boulevard in Culver City is one of the few neighbourhoods left in Los Angeles that has not yet been transformed for the worse by shiny new condos. Blocks of low-rise stucco buildings bear timeworn painted signs: ‘Jesus Saves’, ‘Guns and Ammo’, ‘Ray Blom Plumbing’. If the area hadn’t existed, Doug Aitken could have invented it. The artist has long looked to the mundane and forgotten, an archaeology of a vanishing American culture. His mirrored words or light-box wall pieces often draw from the long horizons and isolation of the West; his appreciation for it surely fated the discovery of his new studio.

Driving along Washington Boulevard four years ago, he saw a hand-lettered ‘For Sale’ sign in front of a transmission repair shop. When Aitken stopped to enquire, he was greeted gruffly by the owner, a man in oily overalls who said he would only sell to someone who worked with his hands. Aitken said he was an artist and it turned out that the owner had done work for Robert Rauschenberg and other artists over the years. After months of courtship, Aitken convinced the owner to sell him the place.

Doug Aitken at his new studio in Culver City, California, located in a former transmission repair shop. The artist was photographed for the November 2019 issue of Wallpaper*, where this article first appeared

Doug Aitken’s new home

It was covered in greasy soot and contained 12 huge hoists for cars, but it was also a rare 1940s bow-truss structure with arched wood ceilings held in place by cross beams instead of interior columns. Following the sale, the owner called him to report that if he redid the signage atop the building within three months, he wouldn’t need a permit to do so. The vertical stack of signs now glows with Aitken’s images of a sunset and the phrase ‘I Don’t Know’. Illuminated at night, it beams across the 405 Freeway.

Not knowing is a philosophical position for Aitken, who seems determined to produce one epic all-consuming project after another. While his video installations – among them Electric Earth (1999), which won him the International Prize at the Venice Biennale, and Song 1 (2012), projected across the entire façade of the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington DC – are exercises in precision, he often embraces making art as a process with unpredictable results, working in the great outdoors, and incorporating elements of performance and live music.

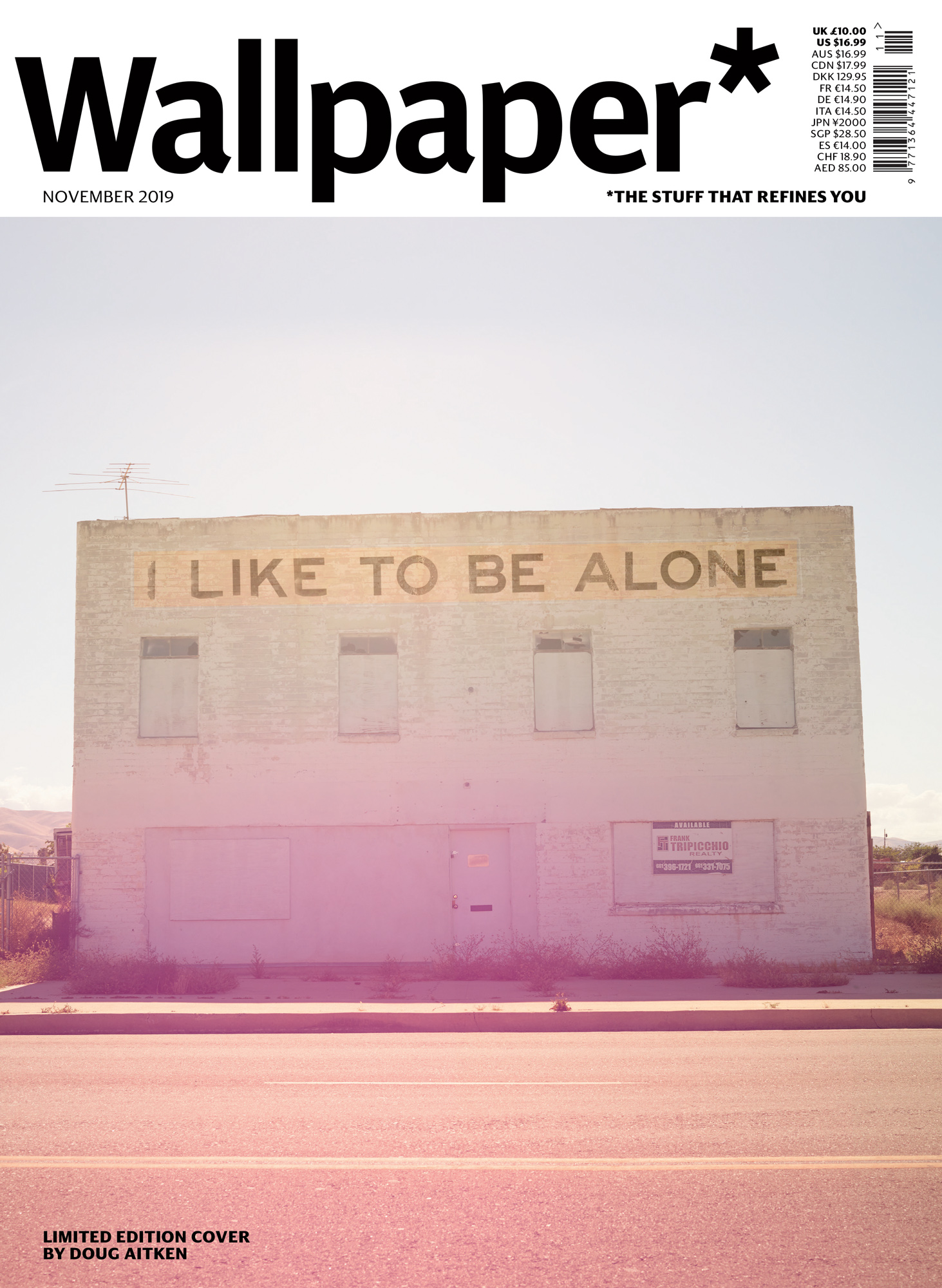

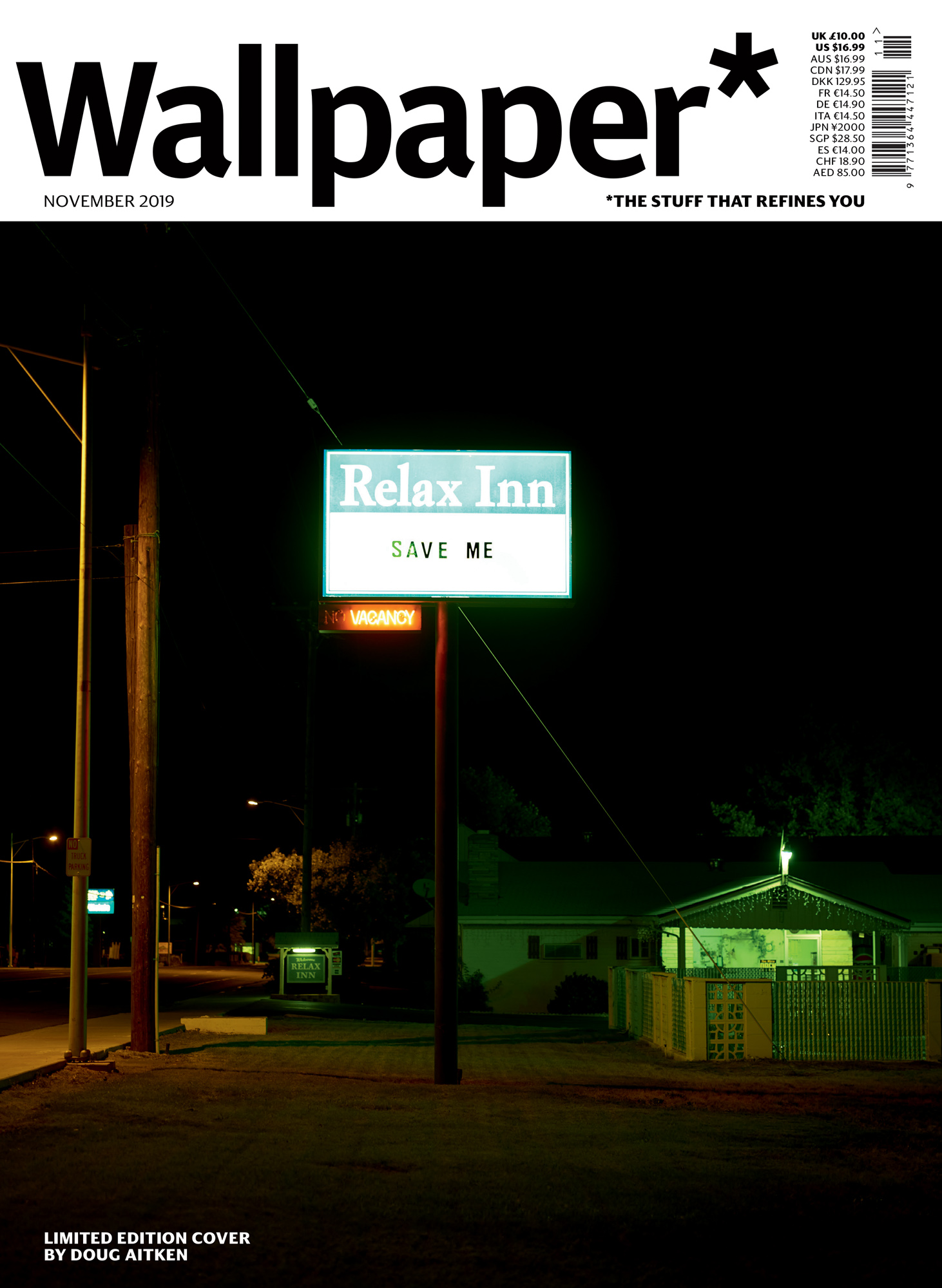

Limited edition cover of Wallpaper* November 2019 by Doug Aitken

Now 51, his hair is starting to grey and a few lines crinkle at the edges of his blue eyes. But he seems to vibrate with energy as he talks about his latest endeavours. In February, he installed a mirror-covered house, Mirage, in Gstaad, reflecting snowy peaks in winter and grassy hills in summer. (Initially shown in 2017 in the desert of Palm Springs, it was also rebuilt inside the State Savings Bank building in Detroit.)

This summer’s project was New Horizon, a 100ft-tall silvery hot-air balloon in which he flew around New England by day and landed at night, when it operated as a kinetic light sculpture that attracted ‘happenings’ – conversations on ideas of the future, as well as live music performances. He calls it ‘Fluxus with a capital F’. The project adds lift to the ideas behind his 2013 Station to Station, when he invited artists, musicians, poets and others to ride on a specially outfitted train that travelled for 23 days from New York to San Francisco. Wherever the train stopped, impromptu gatherings took place on the stations. A version was held at London’s Barbican Centre in 2015.

In the studio, from left, Desert Body, 2019; Inside Out (Chimes/Medium), 2019; Crossroads: Aperture Series, 2019; In Real Life: Aperture Series, 2019; I’ll Be Right Back: Aperture Series, 2019; Earthwork: Aperture Series, 2019; Inside Out (Chimes/Small), 2019; pieces from the Earth Chair series, 2015; and Now (Dark Wood), 2016.

These large-scale projects are mostly produced in the Venice, California, studio that he has owned for 14 years. It’s composed of individual spaces, he explains: ‘My idea was that every room would be a different medium, so you could literally walk from sound to architecture to film, like a parcours of media. There are no objects there. Everything is a sketch, a rendering or an image. It is like a dematerial studio.’

Though Aitken had designed and built a house in Venice, he felt the need for additional studio space with room for the material. ‘I wanted to have more intimacy, living with works before they went away from me and into the public. I had this desire to live with these physical pieces, so I could change them over time.’

The Washington Boulevard studio, 8,000 sq ft with 35 ft ceilings, is a showcase for individual works such as the portfolio of photographs that he put together for the November 2019 issue of Wallpaper* (W*248); mostly pictures of weary, sun-blasted structures with little to distinguish them apart from odd signage added by Aitken. ‘I was noticing that in our cultural, social and political language, there are many new terms. These phrases are distinct time codes to right now. I became interested in taking this new language and inserting it into the everyday.’

Limited edition cover of Wallpaper* November 2019 by Doug Aitken

These phrases disconcert when imposed on his photographs of buildings in desolate locations. ‘These are spaces that are inactive or dormant or in a kind of purgatory, whether that’s a big box chain store on the precipice of going bankrupt or a mini mall that’s lost its signage. I saw it as a way of looking at this incredible friction of 21st-century and 20th-century landscapes.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

And looking at this idea of pushing these questions or ideas into a physical tactile landscape that we’ve created in the past,’ he says. Despite being taken in various locations, they all call to mind the very Culver City area where Aitken found his studio. He says, ‘The great irony is that you find that landscape everywhere you go. It’s really the landscape of repetition, of uniformity. I find myself attracted to those in-between places — locations, sites or architecture —that are the spaces that would go under-recognised or unnoticed.’

RELATED STORY

In the new studio, he is also working on some of the sculptures for his show, ‘Return to the Real’, opening at the Victoria Miro Gallery in east London in October. Giant chrome circular wind chimes are being tuned, while billboard-scale light boxes feature contemporary still lifes. The show includes a more recent project, involving figures of human beings. ‘I had been working away from the gallery space for a while with projects and I found myself, about a year ago, thinking about the gallery space again,’ muses Aitken. ‘But coming back to it with a different perspective. I’d like to do something inside a white room but find a way to really rupture that. The figures of people, milled out of stone or frosted glass, illuminate and emit sound and voices. The works inhabit the space along with the viewers.

‘I always see art as a necessity. You make it because it has to be made’

‘We went to Italy and found slabs of stone with all these layers of strata,’ he continues. ‘When I see them, I see this stacking of deep history. The figure of the body is milled, then severed in half. The inside of the stone body is mirrored metal. The body reflects itself infinitely on the inside, and on the outside it has this weight of geological history. It is very much looking at how we see time on an extremely fast contemporary level, but how we are stuck undeniably in a time code which will continue without us.’

Yet, much of the art in the show is barely visible: just sound or the movement of light. The soundscape that he is composing for the show includes voices repeating the same words and phrases over and over until they become an abstraction. Such vocal soundscapes are a new medium for Aitken, who is also composing a piece for 100 vocalists with the respected LA Master Chorale for a future performance. ‘As we started recording this at my studio, I saw the possibilities of the human voice in a new way. It was an ear-opening discovery,’ he jokes. ‘I wanted to take language beyond representation, and into another space where it becomes architecture. At Miro, it will be a dominant feature.’

Limited edition cover of Wallpaper* November 2019 by Doug Aitken

For all of his skills with digital technology, Aitken is at core a visual artist. He enrolled at Art Center College of Design in Pasadena in 1987, where the fine art faculty included such groundbreaking artists as Mike Kelley and Stephen Prina. He learned how to operate in multiple media, creating music and video along with sculptural installations.

He graduated in 1991 and three years later moved to New York. For a while, he supported himself by taking photographs and doing illustrations for magazines. But he would not be derailed. ‘I have always seen art as a necessity. You make it because it has to be made. Creating is like oxygen; it’s part of what you breathe in and breathe out to stay alive. So I think there is no real separation between art and life.’

Not Yet Titled (Neon), 2019, by Doug Aitken.

It was in New York that Aitken showed his first large-scale installation of footage, Diamond Sea (1997), at 303 Gallery. He moved back to LA in the late 1990s but resisted showing there until 2006, when he joined Regen Projects. (He also shows at Galerie Eva Presenhuber in Zurich.) It was in LA that then MOCA director Philippe Vergne convinced him to do a retrospective, ‘Electric Earth’, in 2017. Aitken sees each of his works as individual and resisted the idea of presenting them as a serial exploration of his career. So Vergne suggested he conceptualise the show as a work of art unto itself. It was a popular and critical hit.

Despite the galleries and the new studio, Aitken has not let go of the idea of ambitious, experiential projects. In September, the Donum Estate unveiled his Sonic Mountain (Sonoma), a site-specific sculpture that mimics the changing effects of wind chimes set in a eucalyptus grove in the rolling hills of the northern California wine country. The sounds and colours from the sculpture are constantly shifting with the conditions of the environment. Perpetual art, you might call it, but it is also a call to pay attention.

‘One of the most profound things that any kind of act of creation can give you is to engage you in the present, to suddenly bring you into the present,’ he says. ‘Those moments are so fleeting and rare, but when you do find them, it is the rarest drug; it’s a private nirvana. It’s something that is inexplicable.’

As originally featured in the November 2019 issue of Wallpaper* (W*248)

Sonic Mountain (Sonoma), by Doug Aitken, at The Donum Estate. Video: courtesy of the artist

Doug Aitken's ‘Return to the Real’ series

Doug Aitken’s Return to the Real series featured as an exclusive portfolio in the November 2019 print issue of Wallpaper*.

‘Return to the Real’ was shown 2 October – 20 December 2019 at Victoria Miro in London

-

Men’s Fashion Week A/W 2026 is almost here. Here’s what to expect

Men’s Fashion Week A/W 2026 is almost here. Here’s what to expectFrom this season’s roster of Pitti Uomo guest designers to Jonathan Anderson’s sophomore men’s collection at Dior – as well as Véronique Nichanian’s Hermès swansong – everything to look out for at Men’s Fashion Week A/W 2026

-

The international design fairs shaping 2026

The international design fairs shaping 2026Passports at the ready as Wallpaper* maps out the year’s best design fairs, from established fixtures to new arrivals.

-

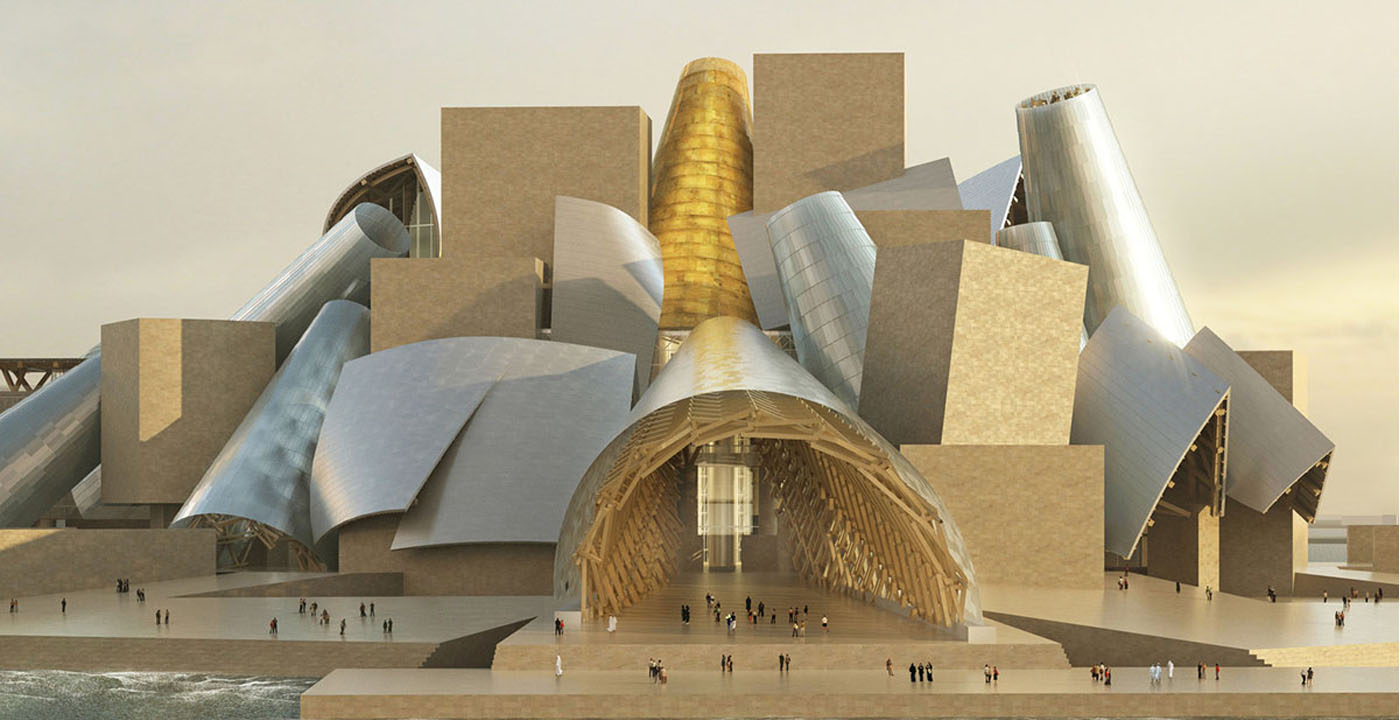

The eight hotly awaited art-venue openings we are most looking forward to in 2026

The eight hotly awaited art-venue openings we are most looking forward to in 2026With major new institutions gearing up to open their doors, it is set to be a big year in the art world. Here is what to look out for

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week'Tis the season for eating and drinking, and the Wallpaper* team embraced it wholeheartedly this week. Elsewhere: the best spot in Milan for clothing repairs and outdoor swimming in December

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekFar from slowing down for the festive season, the Wallpaper* team is in full swing, hopping from events to openings this week. Sometimes work can feel like play – and we also had time for some festive cocktails and cinematic releases

-

The Barbican is undergoing a huge revamp. Here’s what we know

The Barbican is undergoing a huge revamp. Here’s what we knowThe Barbican Centre is set to close in June 2028 for a year as part of a huge restoration plan to future-proof the brutalist Grade II-listed site

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekIt’s wet, windy and wintry and, this week, the Wallpaper* team craved moments of escape. We found it in memories of the Mediterranean, flavours of Mexico, and immersions in the worlds of music and art

-

Each mundane object tells a story at Pace’s tribute to the everyday

Each mundane object tells a story at Pace’s tribute to the everydayIn a group exhibition, ‘Monument to the Unimportant’, artists give the seemingly insignificant – from discarded clothes to weeds in cracks – a longer look

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekThis week, the Wallpaper* team had its finger on the pulse of architecture, interiors and fashion – while also scooping the latest on the Radiohead reunion and London’s buzziest pizza

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekIt’s been a week of escapism: daydreams of Ghana sparked by lively local projects, glimpses of Tokyo on nostalgic film rolls, and a charming foray into the heart of Christmas as the festive season kicks off in earnest

-

Wes Anderson at the Design Museum celebrates an obsessive attention to detail

Wes Anderson at the Design Museum celebrates an obsessive attention to detail‘Wes Anderson: The Archives’ pays tribute to the American film director’s career – expect props and puppets aplenty in this comprehensive London retrospective