Eamonn Doyle on family, loss and facing his grief on the Irish coast

Eamonn Doyle’s mother Kathryn died in March 2017, after a five-year-long battle with cancer. ‘But she never managed to escape the grief of the death of her son,’ the Irish photographer says. Sorting through her possessions, Doyle found piles of notebooks Kathryn had kept hidden from the family.

His mother, he realised, had written countless letters to Doyle’s brother, Ciarán, who, in 1999, had died at the age of 33. ‘There were thousands of them,’ he says. ‘She’d written a letter to him every day. They were like private prayers.’

Reading the letters from his mother to his brother, Doyle became aware that he himself had never dealt with his sibling’s loss, that he had never allowed himself to grieve. Even as he cared for his mother as she mourned, he had not been able to mourn himself.

‘It dawned on me that her death wasn’t just the end of her illness, but the end of her grieving,’ he says. ‘It left a space.’ Her death was traumatic for Doyle, but it also leavened him. He enunciates on the anxiety he had felt during her illness, a malicious foreboding he had never before experienced in his life. After she passed, he felt that weight lifting.

© Eammon Doyle. Courtesy of Michael Hoppen Gallery

He remembers a trip to Ireland’s West Coast after her death. The Dublin-based photographer wanted to try and press on with an separate project that, by his own admission, wasn’t coming together. But he found his mother’s loss would wash over him, like waves, ‘leaving me functioning on autopilot, there in body but not there at all’.

Yet as he tried to make sense of his mourning, visual events coalesced around him. In a car park of a rural hotel, he saw a solitary woman walk past in a long, strikingly traditional mourning veil, her face hidden from him. He didn’t see her again in his stay, as if she were an apparition.

That night, in the same hotel, he happened upon a play performed by a couple. He decided to sit down and watch; the audience comprised himself and ageing woman similar to the age of his mother. The play centred on an artist and his seven muses – each muse played by his partner, and delineated by her donning a veil.

‘It triggered something in me,’ he said. The next morning, he set out on an eight-hour drive down the west coast of Ireland. He had heard of an old slate mine in the southwest coast. It would be there that he found his mother’s headstone. He climbed to the lip of the mine and peered down, and in the depths of the mine saw a grotto, within which stood a Virgin Mary, her hair and shoulders covered in a long flowing veil.

Doyle’s series, which he has titled K, is shot on the Atlantic coast of Ireland, in pools of water, and in the shallows of the shore. The images mostly feature a figure hid beneath – and almost overwhelmed by – a flowing veil as it whips and catches in the Irish wind. He calls her a ‘shapeshifter... a spectral figure changing in colour and materiality as it is pushed and pulled by gravity, wind, water and light.’ He interweaves these portraits with illegible layers of the letters Doyle’s mother wrote to his departed brother. Then there’s slate-grey images of marbled water.

© Eammon Doyle. Courtesy of Michael Hoppen Gallery

‘In the letters, we can make out a word here or there, but the cumulative effect is their appearance as musical notation, of sound,’ he says. There is a distinctly Gaelic, and specifically Irish, form of mourning: what’s known as keening (from the Irish caoinim), a word that translates literally as ‘to wail’. It’s traditionally seen as a female act, a cry over the body of a deceased man. But Doyle seems to have reversed the gender roles – a visual keening from a boy to the woman that bore him.

Doyle shot the series over the course of four days. As we talk, he leafs through the images, pausing to consider each one as if he is encountering them for the first time. ‘I shot the whole series in this incredibly high state of anxiety,’ he says. ‘I can honestly barely remember taking the images.’

He pauses at an image of water, and another, shot at dawn, of the veiled figure K by an idyllic pool. ‘I wanted to find a place to shoot at sunrise,’ he says, ‘And I happened upon this patch of coastline by chance. I can’t really remember doing the shoot. But I realised afterwards that my mother had taught my brother and I – Ciarán was an Olympic swimmer – to swim here when we were children. I’d never come back here, but something led me back to it, without me really realising it, or acknowledge the place in my conscious. It felt like a blind leap of faith, but I was being led by a guiding hand.’

INFORMATION

K, edition of 1000, available at D1 Recordings

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Tom Seymour is an award-winning journalist, lecturer, strategist and curator. Before pursuing his freelance career, he was Senior Editor for CHANEL Arts & Culture. He has also worked at The Art Newspaper, University of the Arts London and the British Journal of Photography and i-D. He has published in print for The Guardian, The Observer, The New York Times, The Financial Times and Telegraph among others. He won Writer of the Year in 2020 and Specialist Writer of the Year in 2019 and 2021 at the PPA Awards for his work with The Royal Photographic Society. In 2017, Tom worked with Sian Davey to co-create Together, an amalgam of photography and writing which exhibited at London’s National Portrait Gallery.

-

Men’s Fashion Week A/W 2026 is almost here. Here’s what to expect

Men’s Fashion Week A/W 2026 is almost here. Here’s what to expectFrom this season’s roster of Pitti Uomo guest designers to Jonathan Anderson’s sophomore men’s collection at Dior – as well as Véronique Nichanian’s Hermès swansong – everything to look out for at Men’s Fashion Week A/W 2026

-

The international design fairs shaping 2026

The international design fairs shaping 2026Passports at the ready as Wallpaper* maps out the year’s best design fairs, from established fixtures to new arrivals.

-

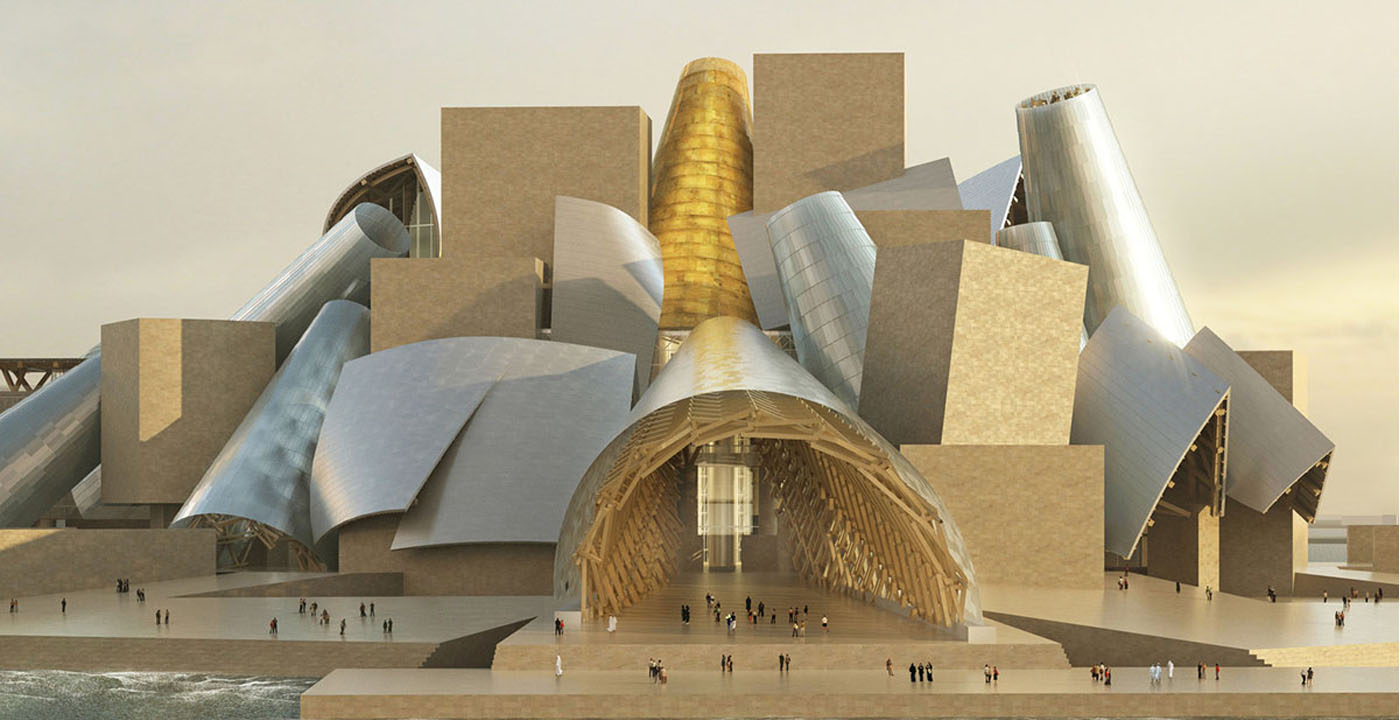

The eight hotly awaited art-venue openings we are most looking forward to in 2026

The eight hotly awaited art-venue openings we are most looking forward to in 2026With major new institutions gearing up to open their doors, it is set to be a big year in the art world. Here is what to look out for

-

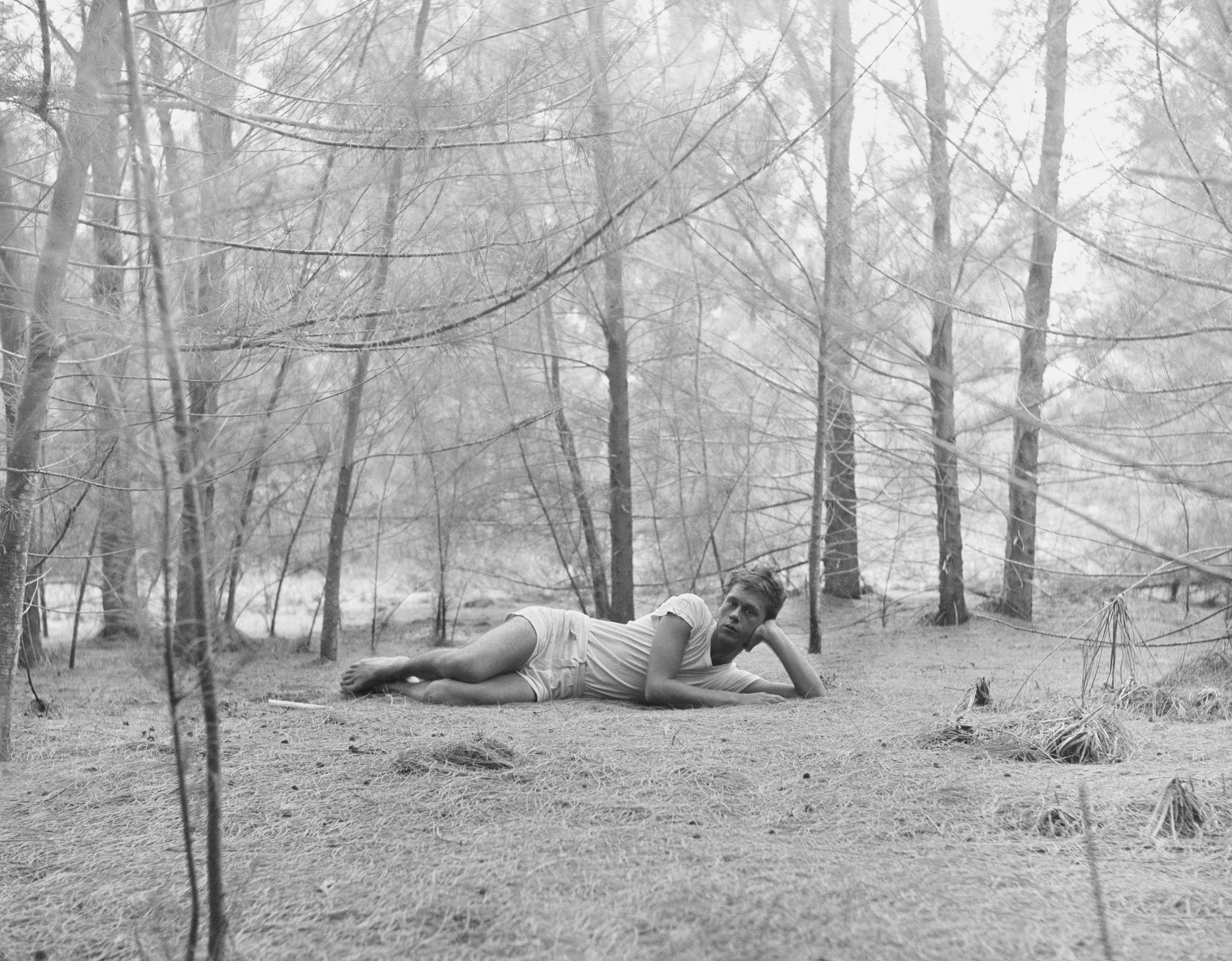

Inside the seductive and mischievous relationship between Paul Thek and Peter Hujar

Inside the seductive and mischievous relationship between Paul Thek and Peter HujarUntil now, little has been known about the deep friendship between artist Thek and photographer Hujar, something set to change with the release of their previously unpublished letters and photographs

-

Nadia Lee Cohen distils a distant American memory into an unflinching new photo book

Nadia Lee Cohen distils a distant American memory into an unflinching new photo book‘Holy Ohio’ documents the British photographer and filmmaker’s personal journey as she reconnects with distant family and her earliest American memories

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekThe rain is falling, the nights are closing in, and it’s still a bit too early to get excited for Christmas, but this week, the Wallpaper* team brought warmth to the gloom with cosy interiors, good books, and a Hebridean dram

-

Inside Davé, Polaroids from a little-known Paris hotspot where the A-list played

Inside Davé, Polaroids from a little-known Paris hotspot where the A-list playedChinese restaurant Davé drew in A-list celebrities for three decades. What happened behind closed doors? A new book of Polaroids looks back

-

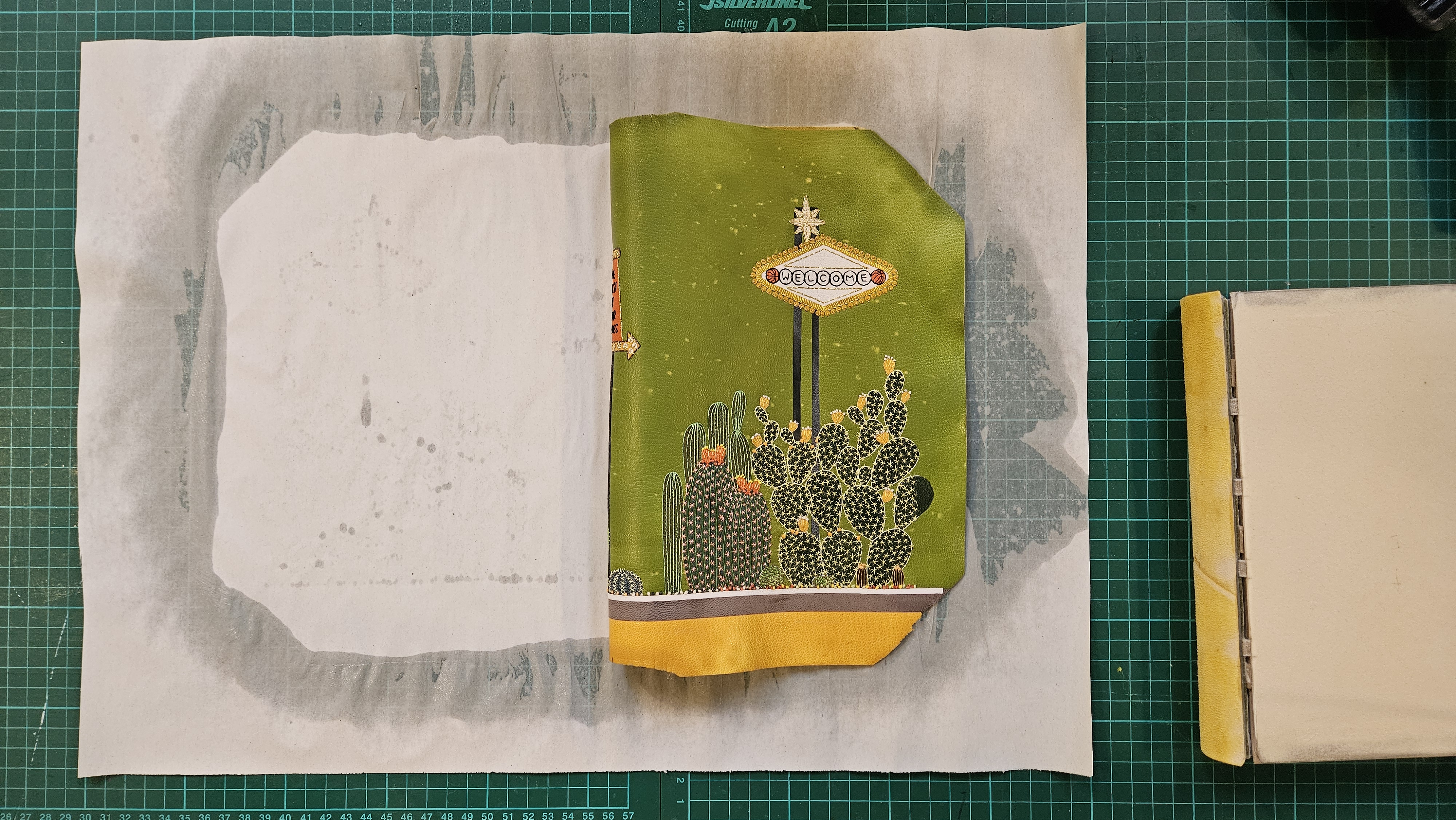

Inside the process of creating the one-of-a-kind book edition gifted to the Booker Prize shortlisted authors

Inside the process of creating the one-of-a-kind book edition gifted to the Booker Prize shortlisted authorsFor over 30 years each work on the Booker Prize shortlist are assigned an artisan bookbinder to produce a one-off edition for the author. We meet one of the artists behind this year’s creations

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekThis week, the Wallpaper* editors curated a diverse mix of experiences, from meeting diamond entrepreneurs and exploring perfume exhibitions to indulging in the the spectacle of a Middle Eastern Christmas

-

14 of the best new books for music buffs

14 of the best new books for music buffsFrom music-making tech to NME cover stars, portable turntables and the story behind industry legends – new books about the culture and craft of recorded sound

-

Jamel Shabazz’s photographs are a love letter to Prospect Park

Jamel Shabazz’s photographs are a love letter to Prospect ParkIn a new book, ‘Prospect Park: Photographs of a Brooklyn Oasis, 1980 to 2025’, Jamel Shabazz discovers a warmer side of human nature