Edward Burtynsky surveys the devastating scale of man’s footprint on the planet

The Anthropocene photographs are huge, imposing and impossibly detailed, designed to stimulate in us a sense of awe – both of the beauty of the natural world, and the destruction our species has wrought upon it. They are images, the photographer says, ‘of a predator species run amok’. But few realise how personal these photographs are to Edward Burtynsky, nor how much they link to his early life.

Burtynsky was born Taras Buratynsky, the son of Ukrainian immigrants who had escaped the Soviet Union for a better life in Canada. He grew up in St Catherines, a small, suburban town not far from Toronto, and spent his spent much of his childhood speaking his parents’ native language.

His father was a hard taskmaster, intent on disciplining the wayward Buratynsky and his siblings. And, while he had a fervent interest in art and a talent at painting, Burtynsky’s father would leave home early and return late, working long shifts on the production line at the local General Motors plant.

Yet, when Burtynsky was barely 11, his father was diagnosed with cancer. By his 15th birthday, he had succumbed to the tumour. Years later, Burtynsky discovered his father had been exposed to contaminates at the plant. As a teenager, he was thrust into the role of breadwinner for his family, and took on work on the same production line his father had worked, and which had contributed to his untimely death.

Chino Mine #5, Silver City, New Mexico, USA, 2012, by Edward Burtynsky. Toronto

Burtynsky’s interest in photography grew through evening classes in Toronto, sat silently at the back after a long day in a factory. From there, he’s risen to his current stature – as the chief author behind one of the largest and most ambitious multimedia projects in the history of photography.

The artist’s Anthropocene project, which he made over four years, explores ‘the age of humanity’ – the almost total impact the human race has had on our planet. The work is based in science and reason, orientated around the research of the Anthropocene Working Group, an international organisation of scientists whom have postulated that the Earth has entered a new geological epoch.

The project features simultaneous exhibition openings at the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto and the National Gallery of Canada, a large-scale monograph published by Steidl, and a feature film, Anthropocene: The Human Epoch, shot in collaboration with filmmakers Jennifer Baichwal and Nicholas de Pencier, and premiered at the Toronto Film Festival. In October, the work will come to Flowers Gallery in London before moving on, next spring, to Fondazione MAST, in Bologna, Italy.

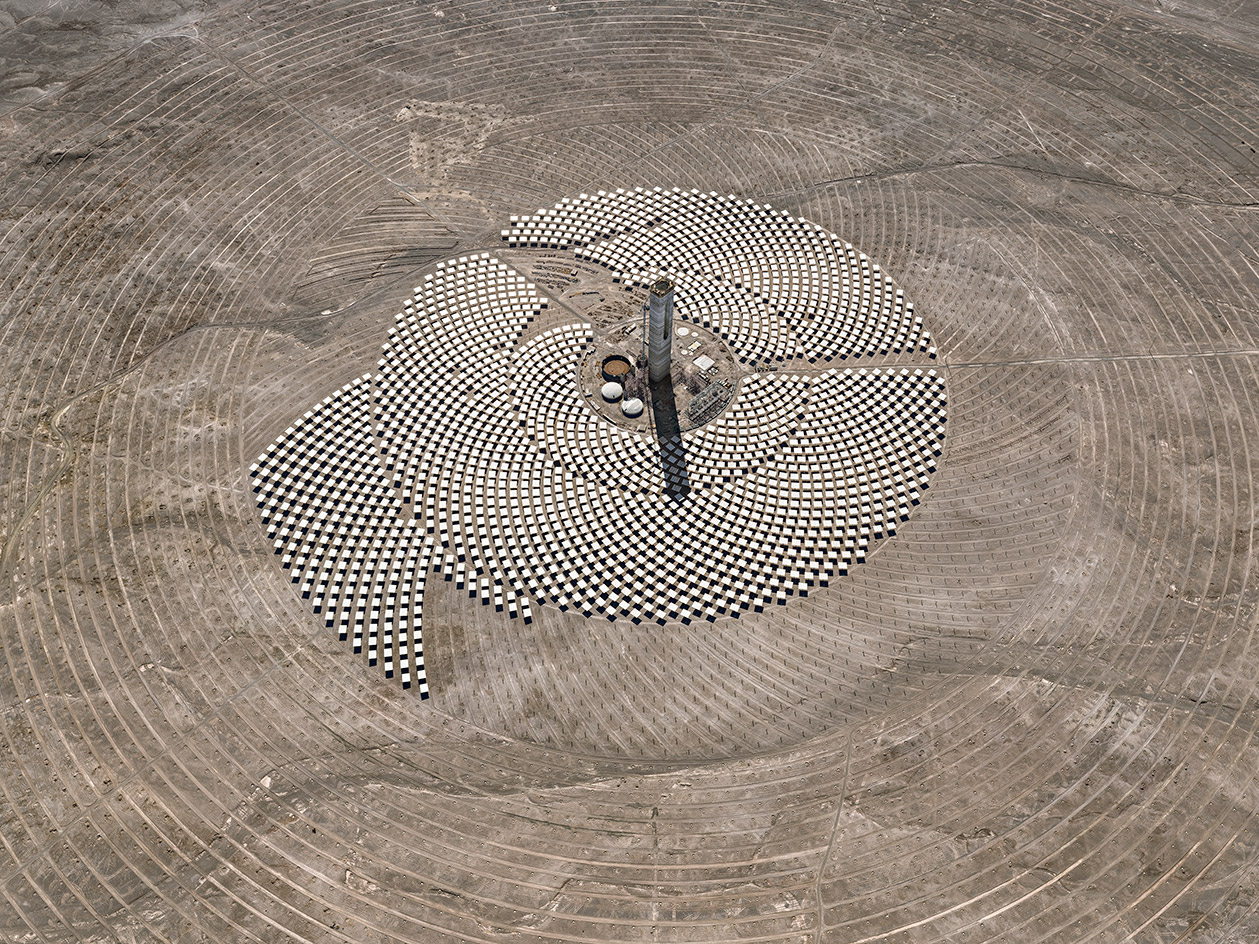

PS10 Solar Power Plant, Seville, Spain, 2013, by Edward Burtynsky. Toronto

Burtynsky’s photographs are often taken from epic aerial or subterranean perspectives, and are presented at a scale far larger and of a higher resolution than most photographers are capable of. In doing so, the artist forces us to consider just how much ancient landscapes have been fundamentally altered by humanity – be it our thirst for water, our need for building materials, or space for our livestock to feed.

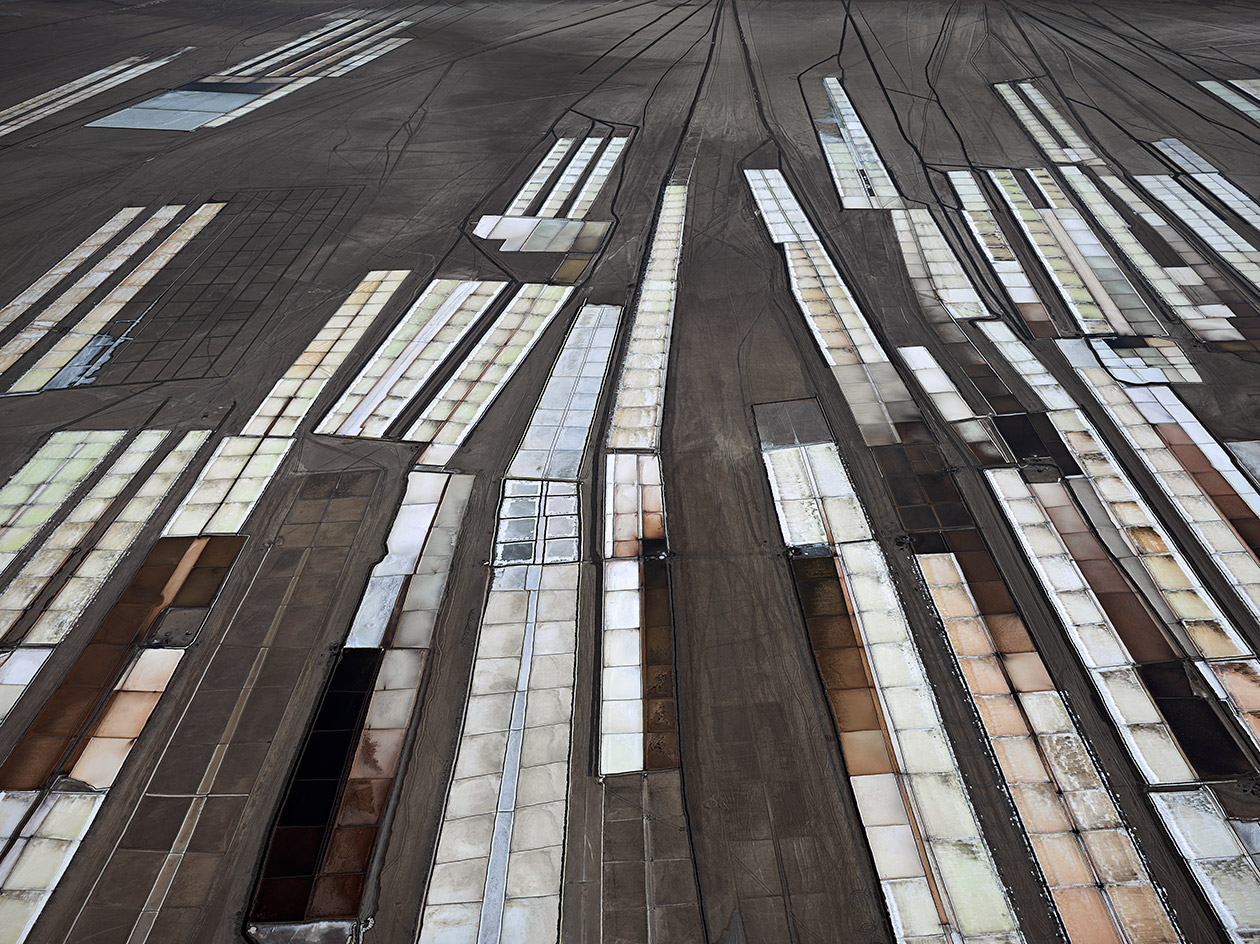

This speed of change reveals how such places can assume a strangely abstracted and surrealistic aesthetic. In his hands, lithium extraction ponds on the salt flats of Chile’s Atacama desert, or the potash mines in Russia’s Ural Mountains, can begin to resemble a Paul Klee etching or a Gerhard Richter painting.

Such photographs are almost head-spinning in their detail. As examples, the exhibitions will include a photograph of a marble quarry in Carrara, Italy, measuring more than 6m long, and comprising 122 exposures. A little further along, we find an image of a coral reef in Komodo National Park, Indonesia, which was captured by a team of ten divers operating 60ft below the surface. The reef is composited from 160 high-resolution images, and measures a total of 200 sq ft.

If that wasn’t enough, Burtynsky has spent considerable time on imbuing the more classical still photographs of the dual exhibitions with augmented reality, deciding that ‘the extension of lens-based media’ would ‘promote experiential understanding of the issues at hand’.

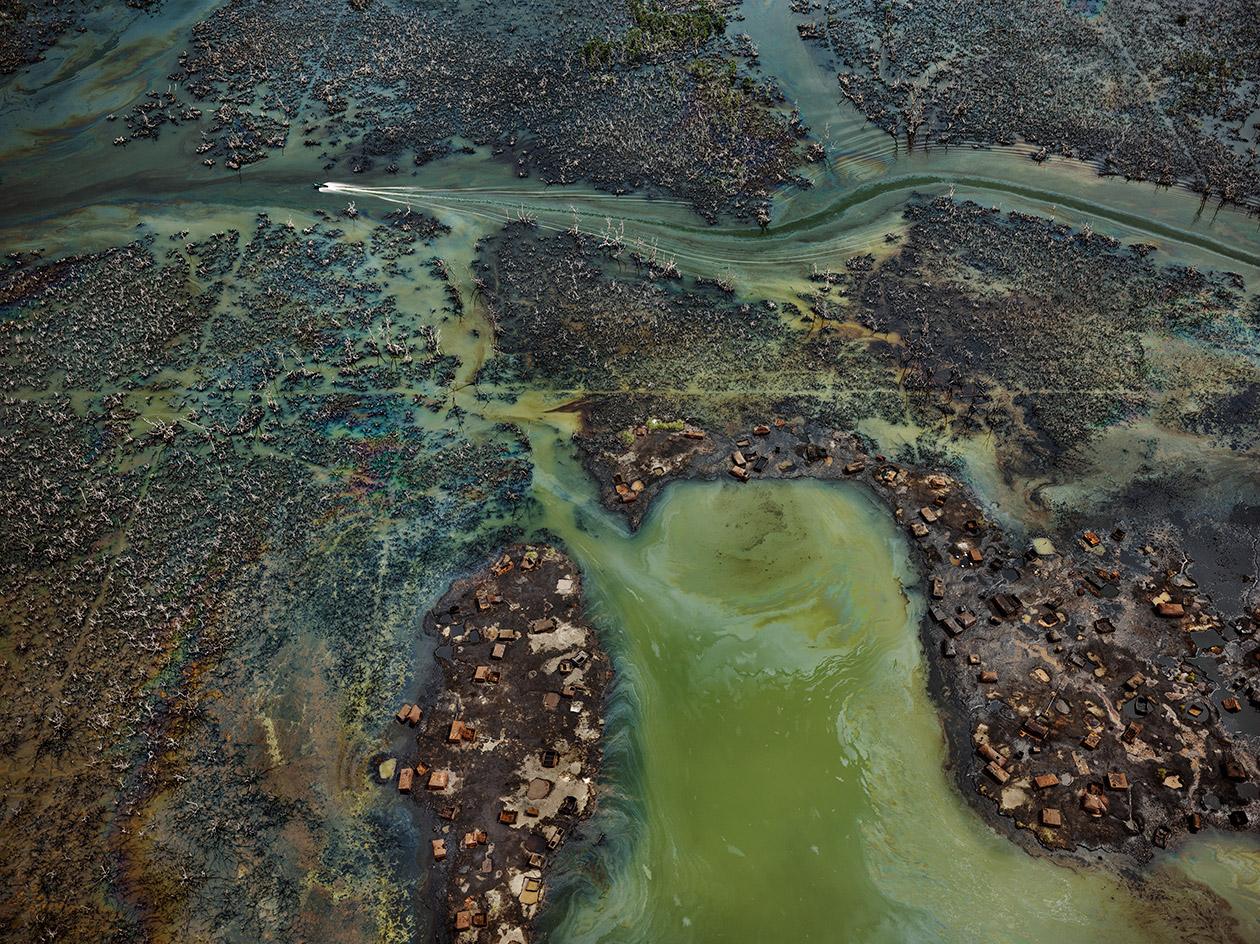

Oil Bunkering #4, Niger Delta, Nigeria, 2016, by Edward Burtynsky. Toronto

At both the National Gallery of Canada and the Art Gallery of Ontario stands a tree measuring 66m high, 12m in circumference and with a canopy spread of 18.3m. The tree is known to locals as ‘Big Lonely Doug’ – Canada’s second largest Douglas Fir tree. From its home on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Burtynsky and his team have transported a near-to-scale AR rendering of the 1,000-year-old tree, which can be seen by visitors using a mobile app designed especially for the exhibitions.

Further inside the shows, the app will then reveal a comparable to-scale rendering of Sudan, the last male northern white rhinoceros, who died in March 2018 at the Ol Pejeta Conservancy in Kenya. Close by is another near-to-scale rendering of the largest pile of elephant ivory found in history, poached from between 6,000 and 7,000 elephants across Kenya, and set on fire at Nairobi National Park in Kenya on 30 April 2016.

Burtynsky is an environmentalist and sees this work as a call to action. ‘Solutions to the problems we face as a species and as stewards of the planet will be found in collaboration and community,’ he says. Yet, behind the rhetoric, there are memories here – of a young, teenage boy who lost his father to out of control industry, and whom, in the most striking way possible, has found a way to answer back.

Watch an exclusive excerpt of Anthropocene: The Human Epoch, by Edward Burtynsky in collaboration with filmmakers Jennifer Baichwal and Nicholas de Pencier, surveying phosphate mines in Florida

Salt Pan #21, Little Rann of Kutch, Gujarat, India, 2016, by Edward Burtynsky. Toronto

Salt Pan #18, Little Rann of Kutch, Gujarat, India, 2016, by Edward Burtynsky. Toronto

Clearcut #5, Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada, 2017, by Edward Burtynsky. Toronto

Highway #8, Santa Ana Freeway, Los Angeles, California, USA, 2017, by Edward Burtynsky. Toronto

Cerro Dominador Solar Project #1, Atacama Desert, Chile, 2017, by Edward Burtynsky. Toronto

INFORMATION

‘Anthropocene’ is on view at the Art Gallery of Ontario until 6 January 2019, and at the National Gallery of Canada until 24 February 2019. For more information, visit Edward Burtynsky’s website

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Tom Seymour is an award-winning journalist, lecturer, strategist and curator. Before pursuing his freelance career, he was Senior Editor for CHANEL Arts & Culture. He has also worked at The Art Newspaper, University of the Arts London and the British Journal of Photography and i-D. He has published in print for The Guardian, The Observer, The New York Times, The Financial Times and Telegraph among others. He won Writer of the Year in 2020 and Specialist Writer of the Year in 2019 and 2021 at the PPA Awards for his work with The Royal Photographic Society. In 2017, Tom worked with Sian Davey to co-create Together, an amalgam of photography and writing which exhibited at London’s National Portrait Gallery.

-

Nikos Koulis brings a cool wearability to high jewellery

Nikos Koulis brings a cool wearability to high jewelleryNikos Koulis experiments with unusual diamond cuts and modern materials in a new collection, ‘Wish’

By Hannah Silver

-

A Xingfa cement factory’s reimagining breathes new life into an abandoned industrial site

A Xingfa cement factory’s reimagining breathes new life into an abandoned industrial siteWe tour the Xingfa cement factory in China, where a redesign by landscape specialist SWA Group completely transforms an old industrial site into a lush park

By Daven Wu

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Beyond tourism: Caribbean artists reflect on its legacy

Beyond tourism: Caribbean artists reflect on its legacy'Fragments of Epic Memory' at the Columbus Museum of Art looks beyond the Caribbean's stereotypes

By Gameli Hamelo

-

Kapwani Kiwanga considers value and commerce for the Canada Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2024

Kapwani Kiwanga considers value and commerce for the Canada Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2024Kapwani Kiwanga draws on her experiences in materiality for the Canada Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale

By Hannah Silver

-

AA Bronson on the radical, enduring legacy of General Idea

AA Bronson on the radical, enduring legacy of General IdeaGeneral Idea, an art group that pioneered a queer aesthetic, is celebrated in a retrospective at the National Gallery of Canada (opened during Pride Month and running until 20 November 2022). Surviving member AA Bronson speaks about their origins, and impact on art and social justice

By Benoit Loiseau

-

Stan Douglas in Venice: a hypnotic chronicle of youth, revolt and liberation

Stan Douglas in Venice: a hypnotic chronicle of youth, revolt and liberationStan Douglas’ captivating two-part exhibition for the Canada Pavilion in Venice is a haunting and meticulous reconstruction of historical events

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith

-

Adam Pendleton’s Canada solo show explores fragmentation of language and representation

Adam Pendleton’s Canada solo show explores fragmentation of language and representation‘These Things We’ve Done Together’, at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA), marks Adam Pendleton’s first solo show in Canada

By Hannah Silver

-

Photographing Montreal's urban spaces at night during lockdown

Photographing Montreal's urban spaces at night during lockdownFollow photographer James Brittain's lens as he explores night time and urban spaces during the recent pandemic lockdown in Montreal, Canada, with his latest series, ‘Night Walks'

By Ellie Stathaki

-

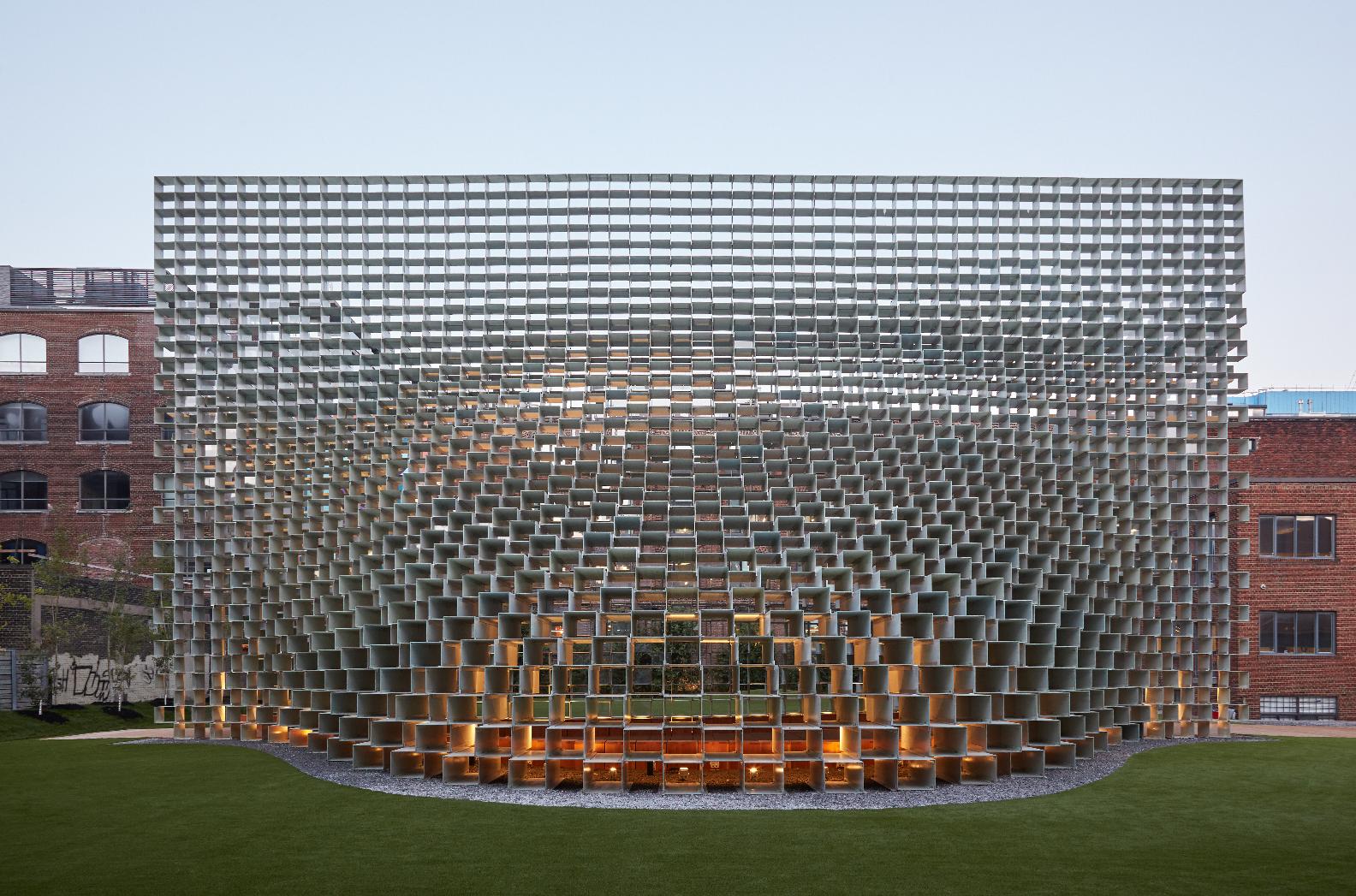

Westbank goes BIG in Toronto

Westbank goes BIG in TorontoBy Alex Bozikovic

-

Night visions: Façade Festival 2016 lights up the streets of Vancouver

Night visions: Façade Festival 2016 lights up the streets of VancouverBy Hadani Ditmars