The creative mind at work: a century of storyboarding at Fondazione Prada

Fondazione Prada’s 'Osservatorio, A Kind of Language: Storyboards and Other Renderings' features some of the most celebrated names in cinema working from the late 1920s up to 2024

‘Somebody told me that Martin Scorsese made drawings, and of course I got curious,’ says curator Melissa Harris about the inspiration behind her new show at Fondazione Prada’s Osservatorio, A Kind of Language: Storyboards and Other Renderings. The exhibition features hundreds of storyboards and other preparatory materials–mood boards, annotated scripts, photos and the like– from some of the most celebrated names in cinema working from the late 1920s up to 2024.

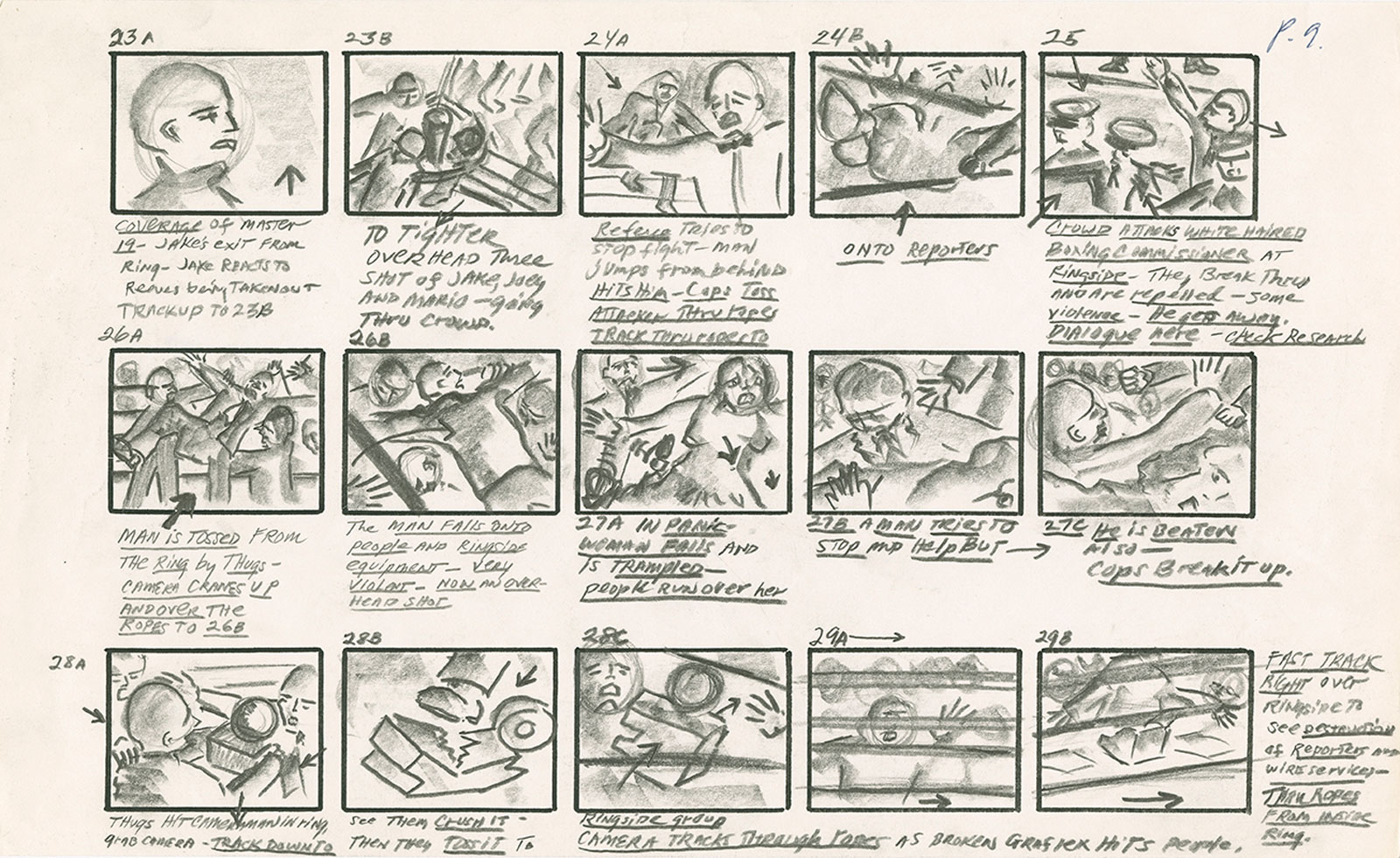

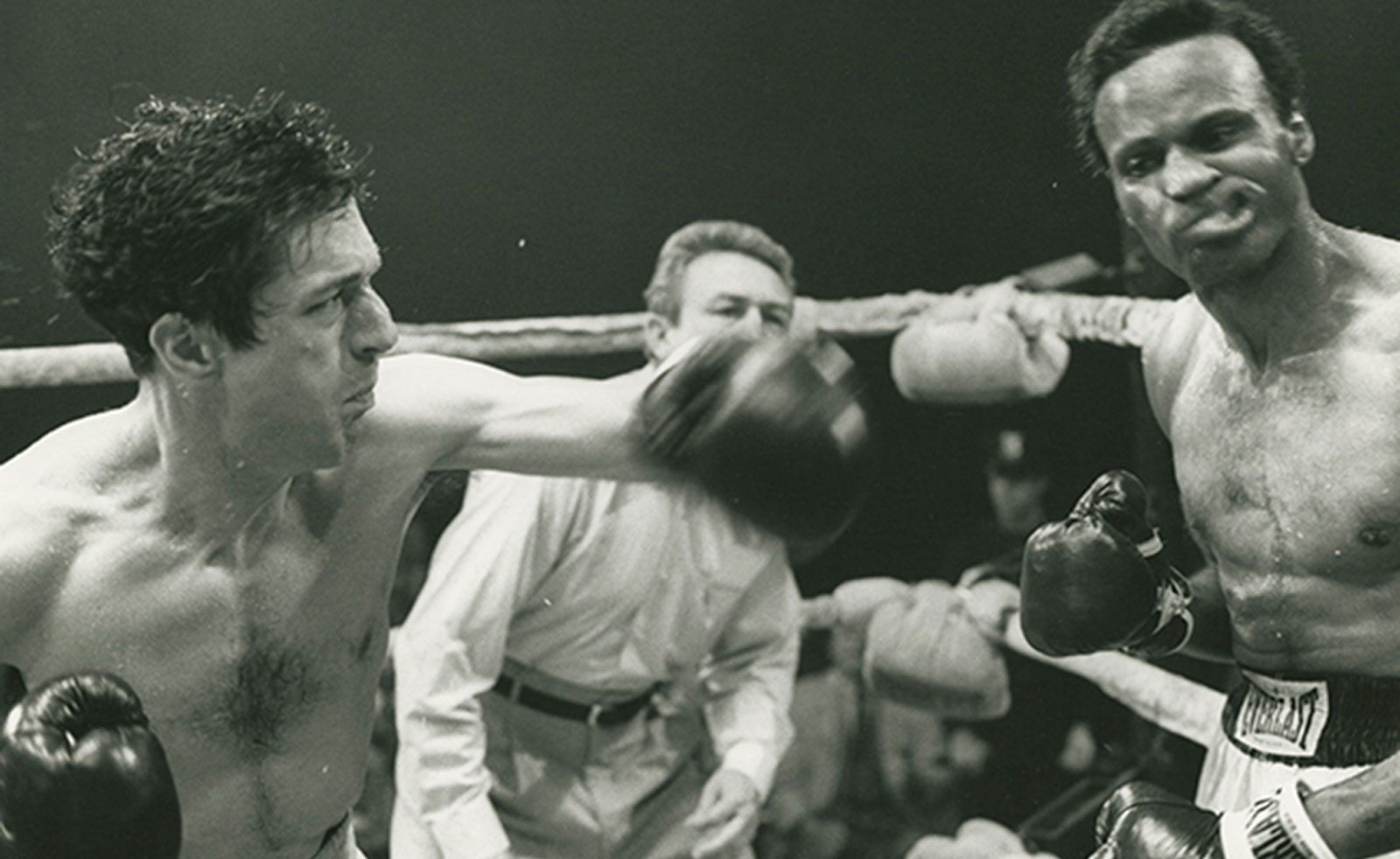

Raging Bull, directed by Martin Scorsese, 1980

Those names include Scorsese, whose drawings for Raging Bull are a highlight, as well as Ingmar Bergman, Agnès Varda, Hitchcock, Hayao Miyazaki, Sophia Coppola, Hitchcock, Spielberg and more. Harris, who has collaborated with Fondazione Prada on two previous exhibitions, wanted to make a show about storyboards because its a subject that is rarely discussed (‘it’s a curators dream to do something fresh!’) and because, as she says, ‘it’s a cool challenge — to do a show about a very human process that is meant to facilitate collaboration, communication.’

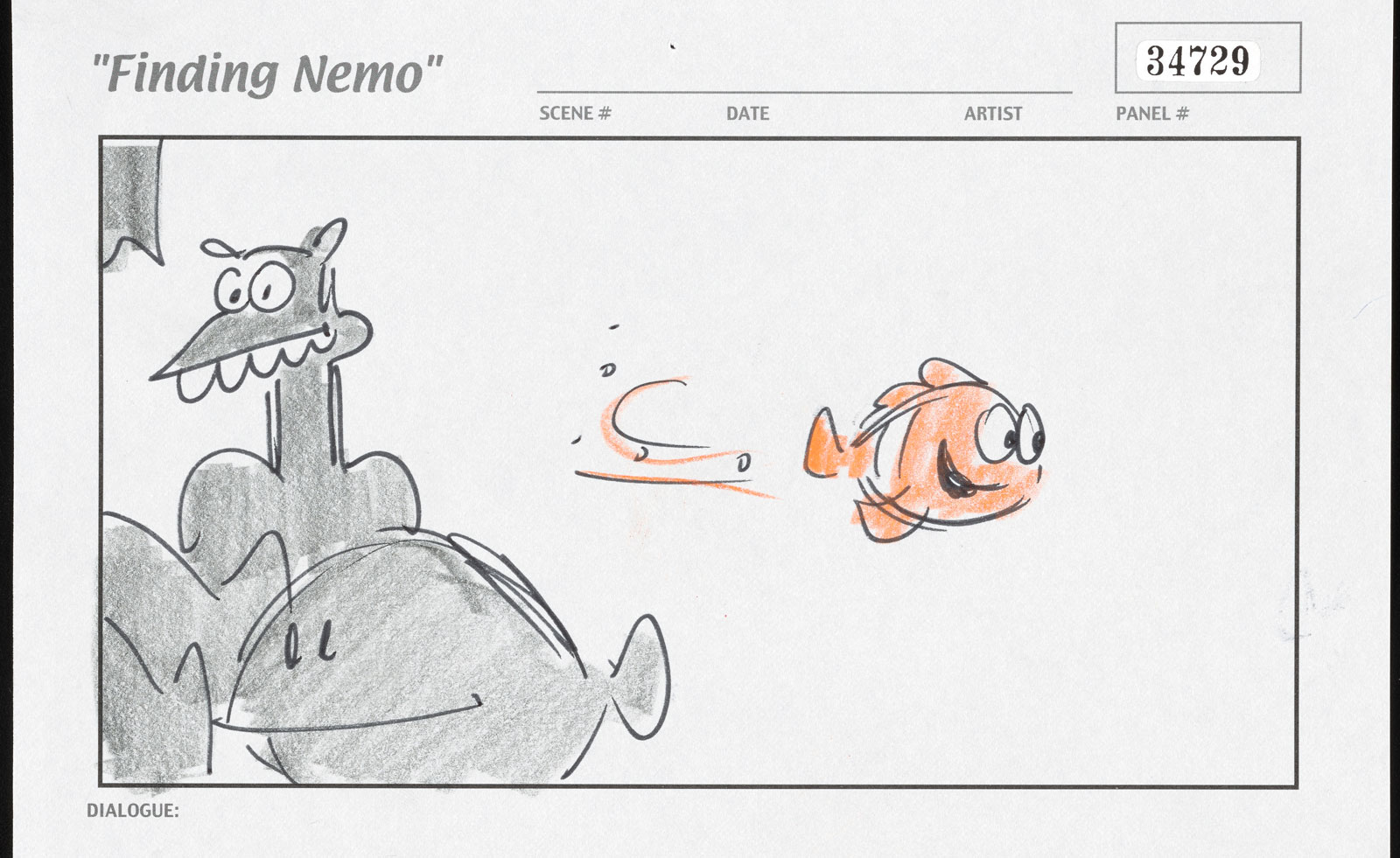

For many, storyboarding is an integral aspect of filmmaking. They are documents that help film teams manifest the narrative, troubleshoot complicated shots, determine the most effective angles for lighting and shooting and more. For Harris the process of collecting and choosing what material was included in the show was ‘about diversity of sensibilities and approaches. We wanted animation and to move through the 20th century into the present. It was like a two-year treasure hunt, without knowing what the treasure was.’

Finding Nemo, directed by Andrew Stanton, 2003. Storyboards by Rob Gibbs, Jason Katz, Bruce Morris and Peter Sohn. Courtesy of Pixar Animation Studios

On the surface, many of the pieces displayed in the exhibit might not seem like treasure at all. While some works are technically impressive, like Disney Studios’ animations for Fantasia or Almodóvar’s comic book-like boards for his 2016 film Julieta, others look exactly like what they are– messy, hastily rendered notes; documents that are made for a specific, practical function. Rather than detract from the exhibit, though, it is exactly what makes it compelling. A Kind of Language is the rare kind of exhibition that celebrates the initial idea of a project, rather than its finished product.

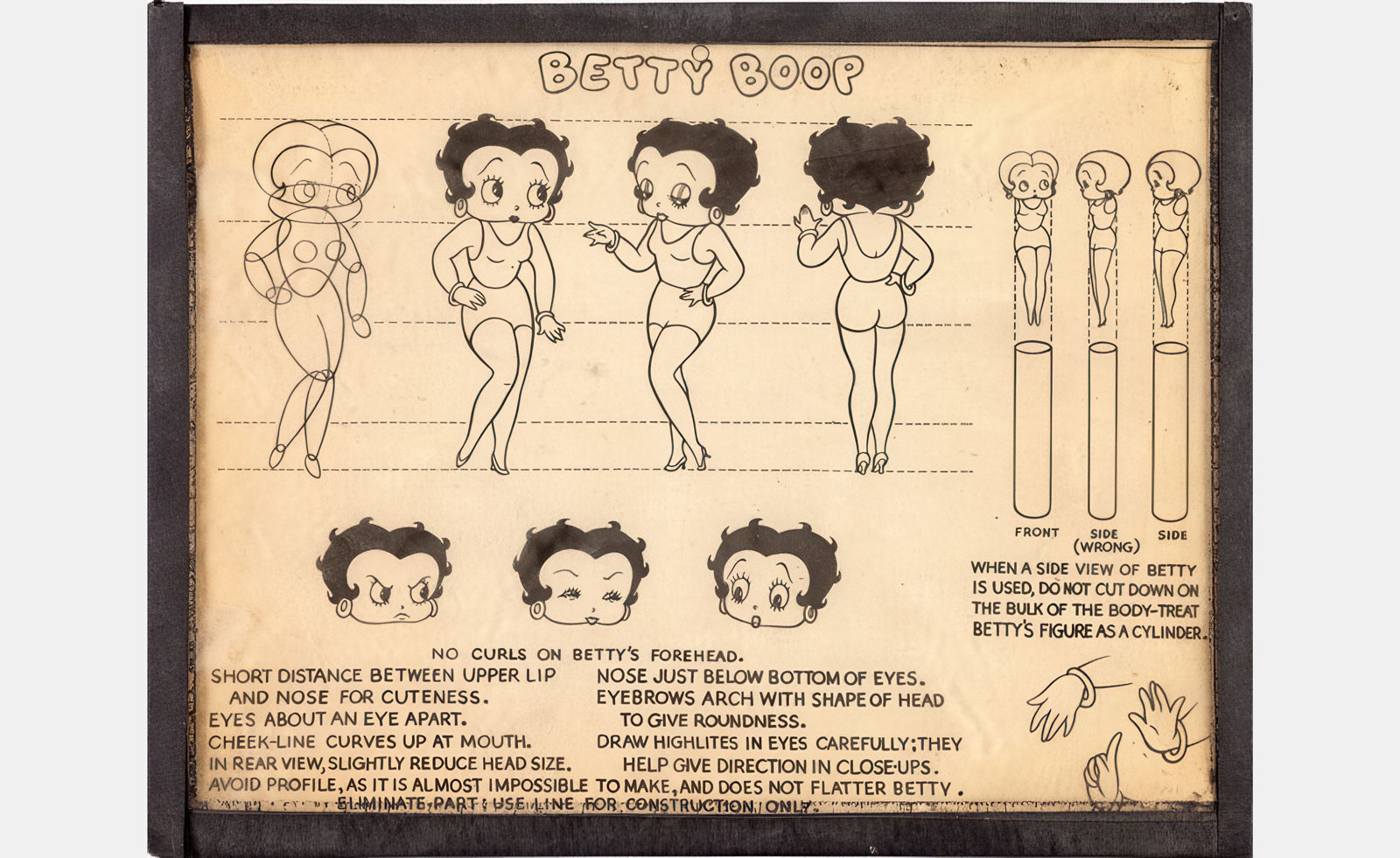

Printed Betty Boop Model Sheet by Fleischer Studios’ staff animators, c. 1930s. Mahoney Family Collection. Ph. Jeni Mahoney, courtesy of the Mahoney Family Collection

For many directors, the storyboard is where they realise their vision of what the film will be before the other forces of filmmaking– the costume, set, DOP and other behind-the-scenes creatives; the location; the actors; the budget– shape that vision into something else, the final product we go to the theater to see. As Scorsese himself once said, ‘drawing the storyboards is my way of visualising the entire film before I shoot it. In a sense, drawing the film as I wish to see it.’ At A Kind of Language we see Fellini’s drawings for Amarcord, an example of how the director, who was a tireless draftsman, used his sketches to realise the details that characterised his eccentric characters. There’s the storyboards for Hitchcock’s Psycho that illustrate how forty-five seconds of the scene are shot from seventy-two different camera positions; as well as Sophia’s Coppola’s rough sketches of The Virgin Suicides sequences and a page of annotated script.

Julieta, directed by Pedro Almodóvar, 2016. Produced by El Deseo. Storyboards by Pablo Buratti Courtesy Pablo Buratti

Stills from Julieta, directed by Pedro Almodóvar, 2016. Produced by El Deseo. Courtesy El Deseo D.A. S.L.U., photos by Manolo Pavón

The presentation of these works is heightened by the unique set design by Andrea Faraguna of the Berlin-based architecture office Sub. Each storyboard is presented on a drafting desk-like table echoing how it might look to stumble upon the workstation of a storyboard artist or director and adding to the sense that you are looking at a work in progress.

Seen all together, the documents that make up A Kind of Language present a diverse and compelling showcase of the creative mind at work. As Harris says, ‘working on this show has given me a greater appreciation for the intense and often nuanced complexities of communicating and collaborating while making a film. I love that it is ultimately a very human and visual process, and it’s this sense of joining forces to realize a vision that I hope is part of the take-away for visitors to the show (and of course I hope they enjoy and appreciate what they experience as well!).'

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Fondazione Prada’s 'Osservatorio, A Kind of Language: Storyboards and Other Renderings' is on until 8 September 2025

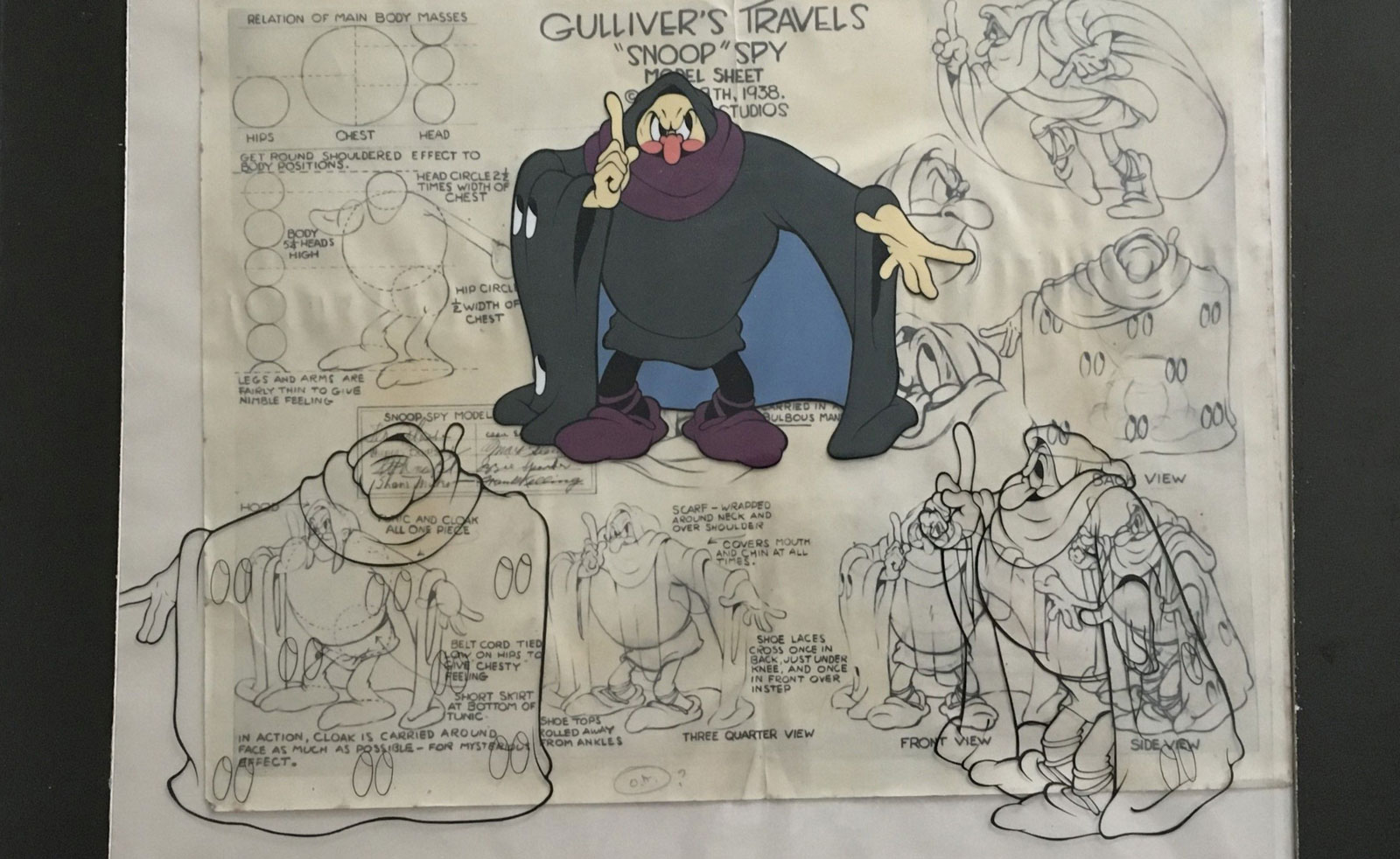

Printed Snoop Model Sheet with Color Cel Overlay by Fleischer Studios’ staff animators, c. 1939. Mahoney Family Collection. Ph. Jeni Mahoney, courtesy of the Mahoney Family Collection

Mary Cleary is a writer based in London and New York. Previously beauty & grooming editor at Wallpaper*, she is now a contributing editor, alongside writing for various publications on all aspects of culture.

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss

-

Pino Pascali’s brief and brilliant life celebrated at Fondazione Prada

Pino Pascali’s brief and brilliant life celebrated at Fondazione PradaMilan’s Fondazione Prada honours Italian artist Pino Pascali, dedicating four of its expansive main show spaces to an exhibition of his work

By Kasia Maciejowska

-

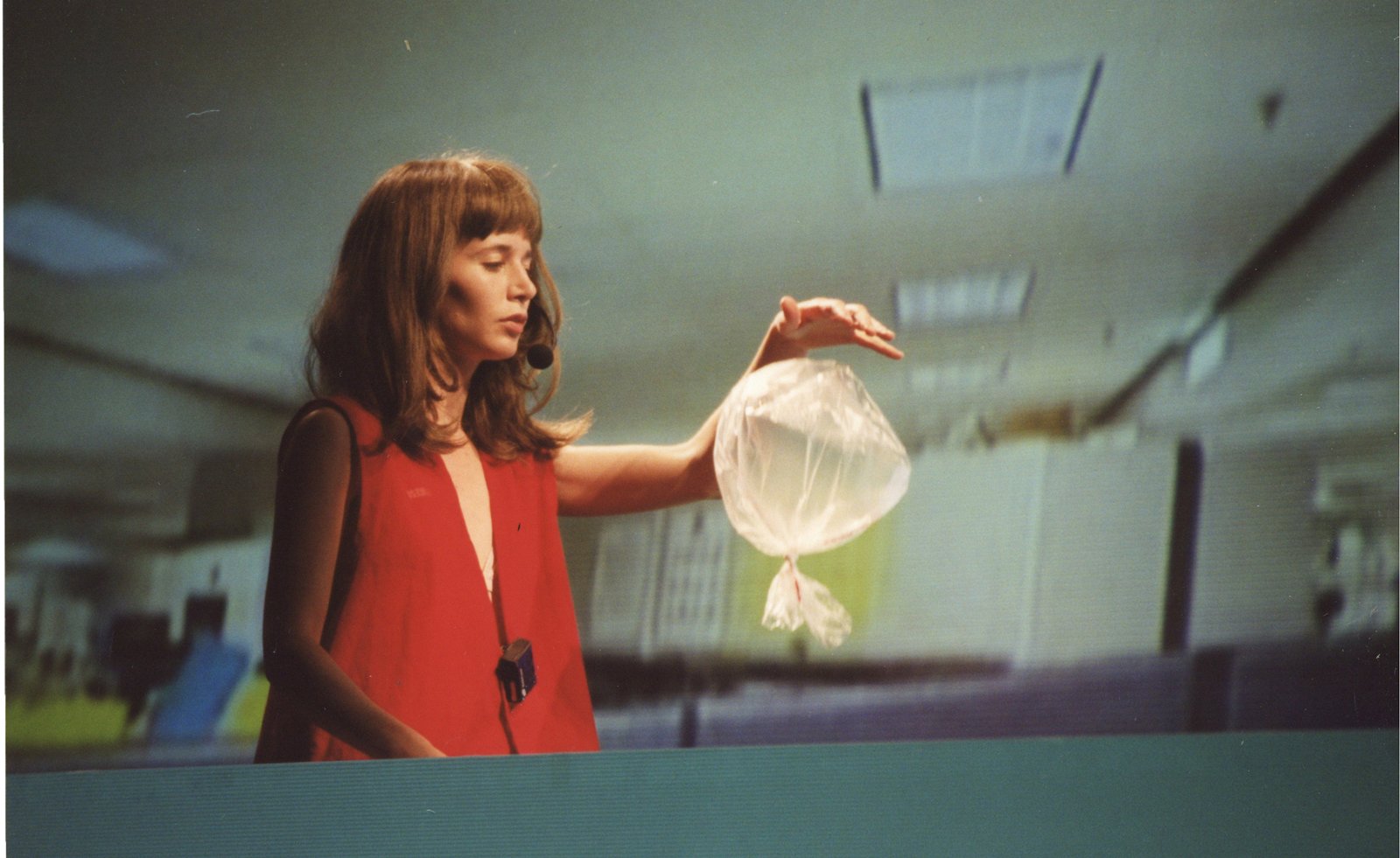

Miranda July considers fantasy and performance at Fondazione Prada

Miranda July considers fantasy and performance at Fondazione Prada‘Miranda July: New Society’ at Fondazione Prada, Milan, charts 30 years of the artist's career

By Mary Cleary

-

Fondazione Prada exhibition is an ode to a vanishing Venice

Fondazione Prada exhibition is an ode to a vanishing VeniceAt Fondazione Prada’s 18th-century Venice palazzo, group exhibition ‘Everybody Talks About the Weather’ straddles beauty and fear and probes Venice’s precarious environmental future

By Will Jennings

-

Elmgreen & Dragset in Milan: bodies, minimalism and home discomforts

Elmgreen & Dragset in Milan: bodies, minimalism and home discomfortsElmgreen & Dragset’s new show at Milan’s Fondazione Prada is an uncanny exploration of our dematerialising bodies and increasingly discomforting homes

By TF Chan

-

Fashion's finest moments at Frieze Los Angeles 2022

Fashion's finest moments at Frieze Los Angeles 2022By Laura Hawkins

-

Picture this! Jason Lloyd Evans' fashion show archive

Picture this! Jason Lloyd Evans' fashion show archiveThe British photographer shares his favourite backstage images, from the runway shows of Prada, Louis Vuitton, Balenciaga and more

By Laura Hawkins

-

In memoriam: Germano Celant (1940-2020)

In memoriam: Germano Celant (1940-2020)The Italian art historian, curator and father of Arte Povera has died aged 80. Here, Nicholas Cullinan, director of London's National Portrait Gallery, pays tribute

By Nicholas Cullinan

-

Prada Mode pop-up club opens in Miami with intervention by artist Theaster Gates

Prada Mode pop-up club opens in Miami with intervention by artist Theaster GatesBy Sujata Burman