Step into Andrew Cranston’s magical take on mundanity at The Hepworth Wakefield

As ‘Andrew Cranston: What made you stop here?’ opens at The Hepworth Wakefield, the artist tells us about seeing the extraordinary in the everyday

‘In the daily experiences of my life I do find a lot of subject matter,’ says Scottish artist Andrew Cranston, currently showing at The Hepworth Wakefield. ‘Or it finds me perhaps? A sense of dawning recognition and opportunity. A feeling it was under my nose all the time, hiding in plain sight. Time itself works some sort of magic upon ordinary things and they become interesting to me. My life is pretty routined, as I think a painter’s life needs to be. I do the same or similar things most days. Looking and seeing things all around me (seeing being quite a different thing from looking).’

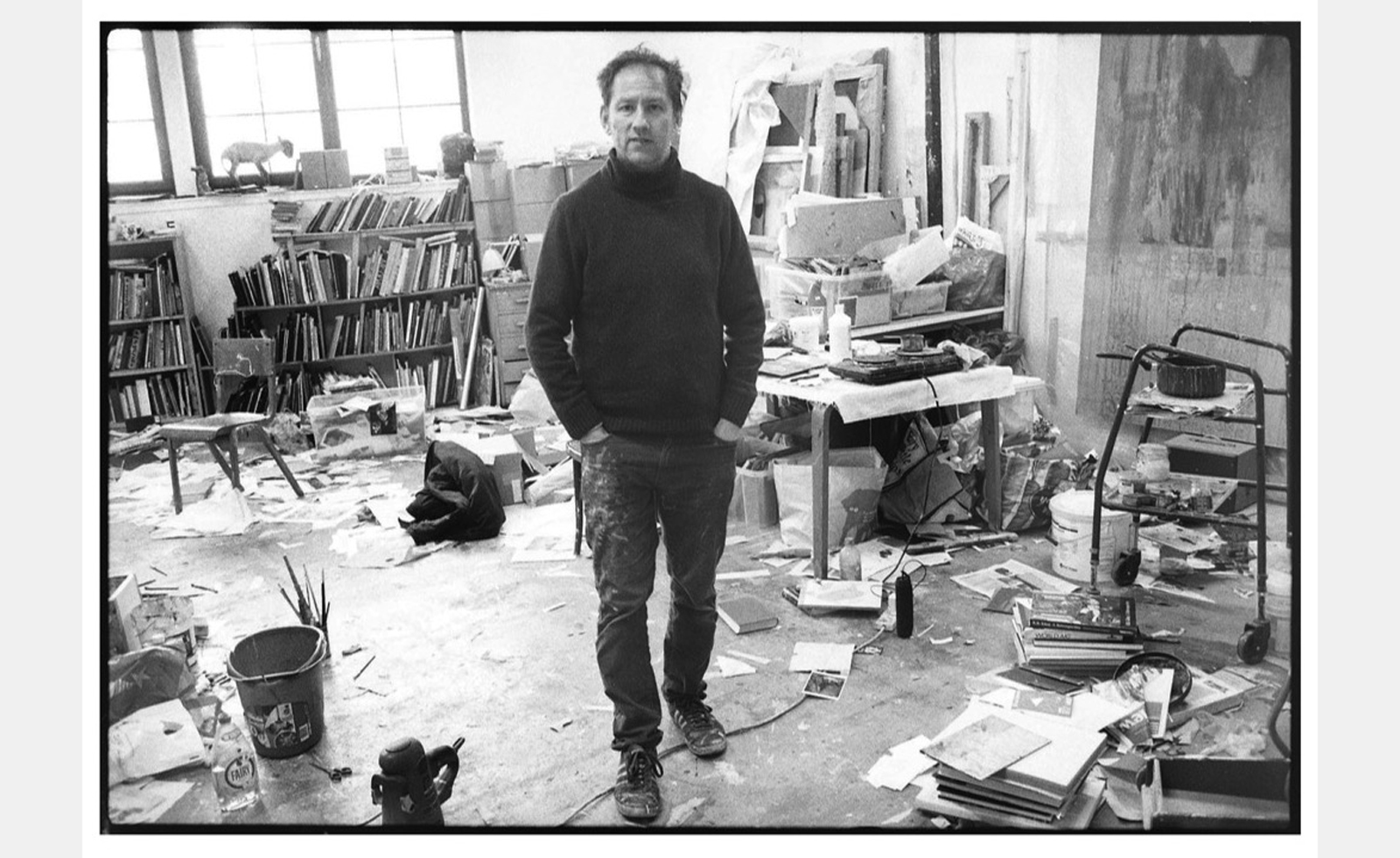

Andrew Cranston in his studio, Glasgow, 2020

Cranston’s translation of this minutiae of everyday life is the focus of ‘Andrew Cranston: What made you stop here?’ at The Hepworth Wakefield, his first solo show at a UK public institution, which unites 38 new and recent paintings, from the large to the small scale. His paintings encompass landscapes and portraits as well as the everyday details that fascinate him, beautifully recorded in rich and evocative scenes.

‘I find something extraordinary and often strange and hidden in them,’ says the artist. ‘James Joyce found something heroic in the everyday and in Ulysses presented a single day in the life of various Dubliners, in all its minutiae, as epically as a Greek myth. I find everyday life anything but mundane: the pleasures of eating and drinking, the changeable weather of thought, our bodies as barometers. I am not at all religious and never have been but I always keep returning to a daily cosmic shock that all of this appears to be real, an amazement that there is consciousness, existence, life. That there is something rather than nothing.’

Andrew Cranston, Cat and cheeseboard, 2018

Alongside a series of large-scale canvases are more intimate works painted on linen-bound book covers, in a nod to the autobiographical and cultural references Cranston weaves throughout his work. ‘Some artists develop a persona alongside their work,’ he adds. ‘I haven’t, and I’m not interested in playing a “character”. But I always have self-mythologised, at least internally, and have long practised connecting my thoughts and feelings to ones I see mirrored in literature, cinema, and painting or to situations in politics or sport.

‘It’s a habit of the imagination, a knack for dramatising. It’s also a fictionalising tendency, to make versions of reality. Painting is a language and you can use it to say all sorts of things, to speak the “truth”, record objectively or make some sort of rhetorical proposition, from a certain vantage point. Are the paintings of Brueghel autobiographical? On some level, probably yes, by choosing what he painted and how he painted, inevitably yes.’

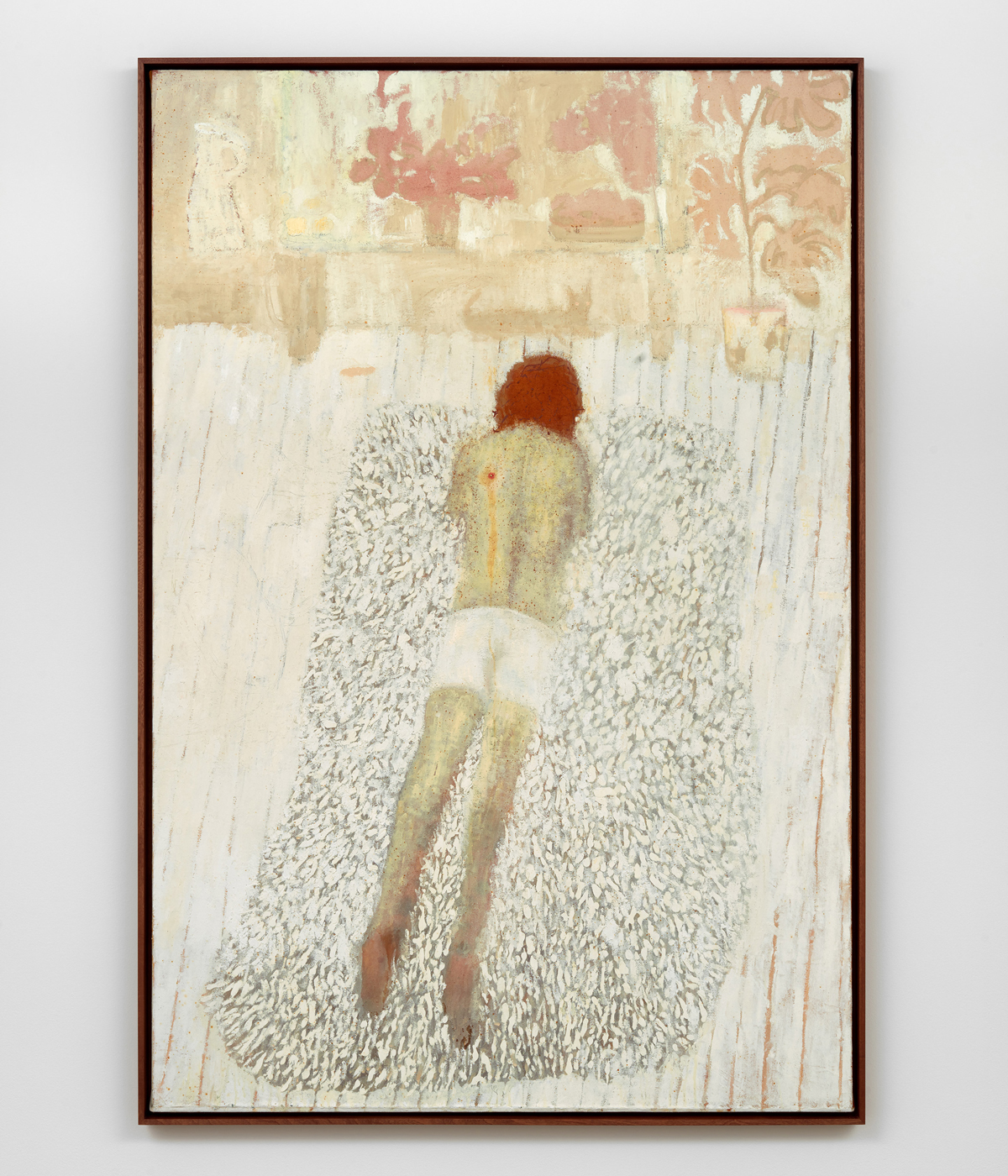

Andrew Cranston, Why can't I be you?, 2022

Appropriately for paintings that cast doubt on the accuracy of memory, instead creating a very strong time and place of their own, Cranston gives no thought to what happens when his dreamlike works leave his studio and enter the world. ‘I paint with no sense of audience really, or if I do it is an audience of other painters. Like a lot of artists, I spend a lot of my time alone, locked into my own game of puzzle-making and problem-solving that is as absurd as it is addictive. It can feel quite selfish. At the end of this – though there is no end to this Sisyphus stuff – the work goes out into the world and has its own life, somehow independent from me. Then I feel less selfish and I am happy to let them go and tend to the new life forms that I have hatching.

‘With small paintings and large paintings, there can be a contrast of how we react through our bodies, whether, in a small work, we have to peer into it, put on glasses, adjust to its inner scale, or on the other hand, with a large work, be more in the painting enveloped by its scale. I hope viewers get drawn in and held for some length of time, experience some sort of pleasure or pathos, are transported somewhere else, perhaps into the painting itself.’

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

'Andrew Cranston: What made you stop here?' is at The Hepworth Wakefield 25 November 2023 – 2 June 2024

Andrew Cranston, Stay with me, my nerves are bad tonight, the midges too, 2022

Hannah Silver is the Art, Culture, Watches & Jewellery Editor of Wallpaper*. Since joining in 2019, she has overseen offbeat design trends and in-depth profiles, and written extensively across the worlds of culture and luxury. She enjoys meeting artists and designers, viewing exhibitions and conducting interviews on her frequent travels.

-

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressing

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressingPart of our monthly Uprising series, Wallpaper* meets Benjamin Barron and Bror August Vestbø of All-In, the LVMH Prize-nominated label which bases its collections on a riotous cast of characters – real and imagined

By Orla Brennan

-

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationship

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationshipAnnouncing their marriage during Milan Design Week, the brands unveiled a collection, a car and a long term commitment

By Hugo Macdonald

-

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craft

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craftThe heritage furniture manufacturer is training a new generation of leather artisans

By Cristina Kiran Piotti