Dan Flavin’s fluorescent lights light up Basel

‘Dedications in Lights’ celebrates Dan Flavin’s conceptual works, at Kunstmuseum Basel

What Dan Flavin did with a simple strip light seems almost a form of magic when we see it today. Instantly recognisable as a unique, conceptual work of art, each piece was constructed from standard lighting tubes, which are available in a very limited number of sizes and colours. By operating within the constraints of his chosen material, Flavin was able to create a lifetime’s body of work.

‘Dedications in Lights’ at Kunstmuseum Basel looks at Flavin’s ‘dedicated’ works. While most of his art was untitled, he would often name works as a dedication to a loved one, a friend, an artist he admired; he even dedicated one work to his dog.

The show opens with The diagonal of May 25, 1963 (to Constantin Brancusi), the yellow almost a buttercup shade as it faces A primary picture, 1964, a fluorescent lights frame sitting at picture height, one side flush to the doorway as is instructed with some of the works.

Flavin rejected the idea that he was a minimalist and refused to participate in minimalist group exhibitions, but the minimalist principles he employed, such as letting the material dictate the work, mean that he is absolutely considered one.

Dan Flavin’s ‘Dedications in Lights’

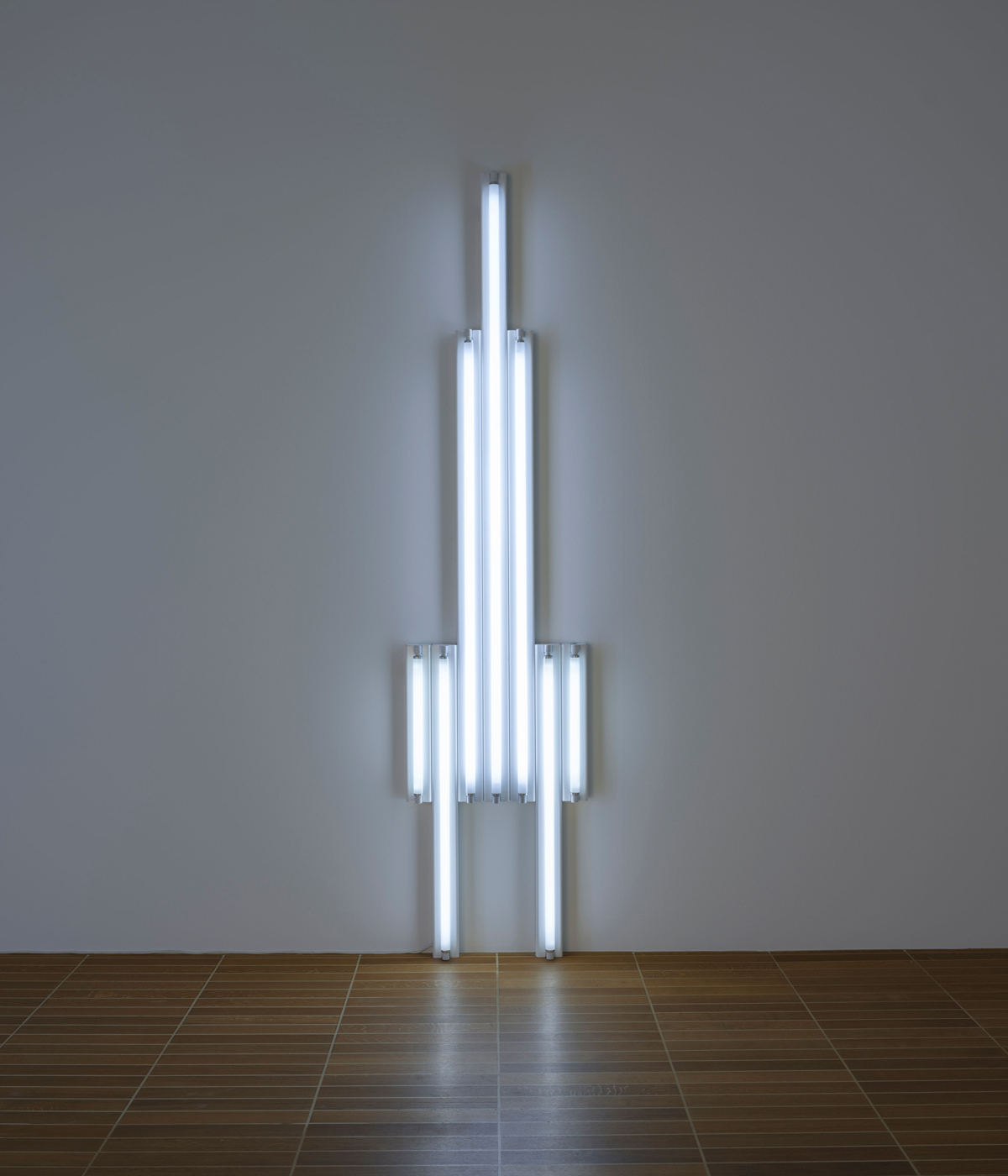

Dan Flavin, ‘Monument’ 7 for V. Tatlin, 1964

Josef Helfenstein, the outgoing director of Kunstmuseum Basel, had planned to stage a Flavin exhibition since he took on the role in 2016.

‘I think to use light as a source and a vocabulary is in a way crazy, and to use such a totally banal thing like the fluorescent tube, and to produce so much complexity…’ says Helfenstein. ‘It's unbelievably simple and shockingly reductive to work with this prefabricated stuff that comes in four different sizes and in just six colours, with four different whites, and that's all you have to develop your own work. Just looking at this show, the complexity of what he has produced is impressive.’

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

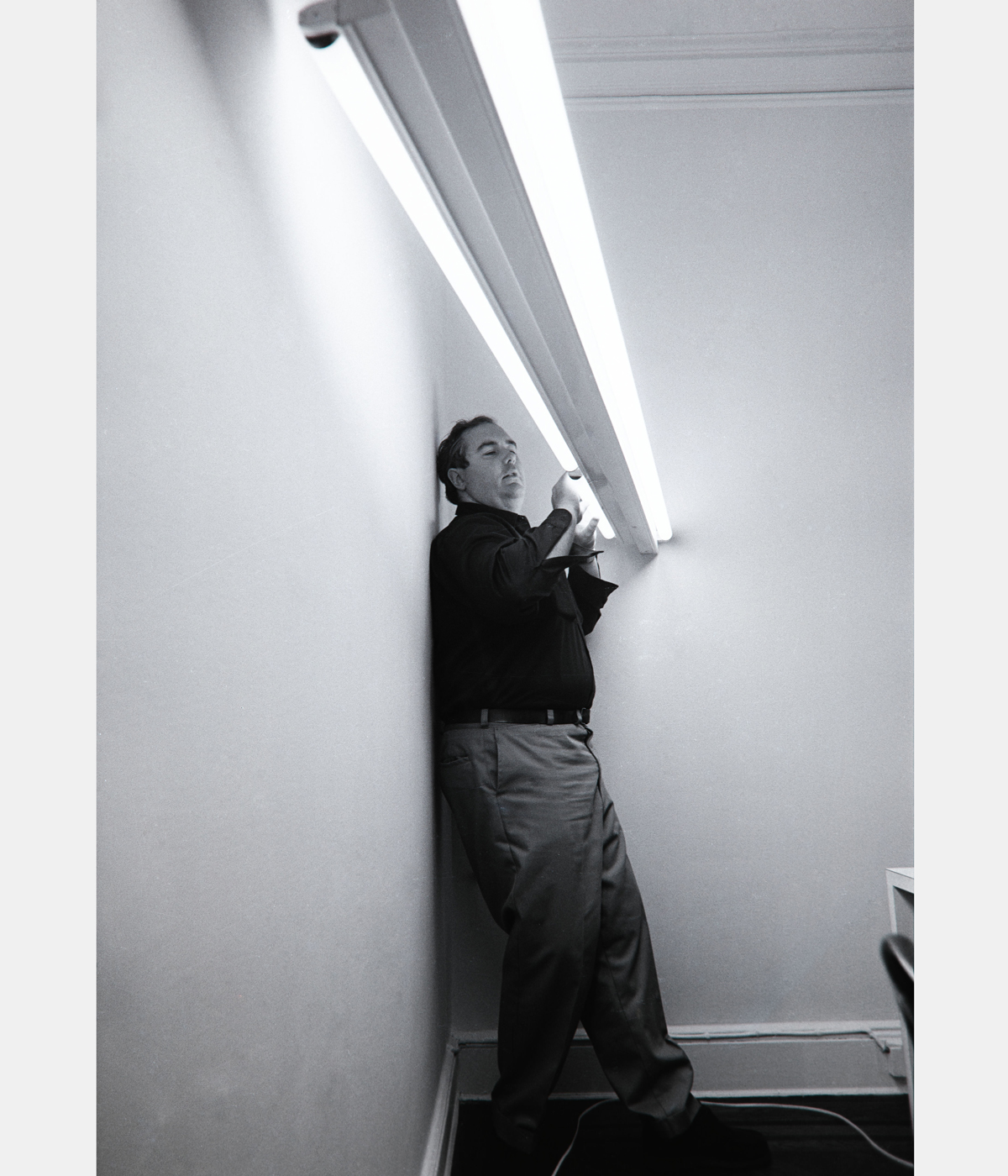

While Flavin’s sculpture undoubtedly leans towards genius, he was famous for his idiosyncrasies, and while he would design and instruct all of his work, he didn’t believe in working with his hands. This means that all the wiring and construction was done by his first wife Sonja Severdija, up to 1979 when they divorced.

Dan Flavin, Untitled (to my dear bitch, Airily) 2, 1984

‘She did everything that's done by hand,’ explains curator Olga Osadtschy. ‘At the beginning, Flavin would construct these icons; you can see them in the Judd Foundation, for example. They are square objects made of wood or linoleum with lamps protruding out of them and she would build those. So everything where you would need a hammer or a screwdriver, that's her.’

The warmth or sentimentality of Flavin’s dedications to friends and colleagues contradict his prickly reputation. He dedicated many works to Russian constructivist Vladimir Tatlin, and the exhibition has a room given over to these works that were made in the early 1980s, in shades of white with occasional accents of red. A series of six complex works made in 1991 are dedicated to German artist John Heartfield, and feature in the final room of the show.

Flavin was also very politically active and anti-war, designing posters and organising rallies for an opponent of President Nixon, ‘artists’ politician’ George McGovern, to whom he dedicated work. He also created a red work shaped like a plane or a crossbow during the war with Vietnam, Monument 4 for those who have been killed in ambush (to P. K. who reminded me about death), 1966, for a group show at the Jewish Museum in New York, curated by Kynaston McShine. The work was later installed to light a dancefloor, and mentioned as drenching dancers in blood by singer-songwriter and poet Patti Smith in her memoir Just Kids.

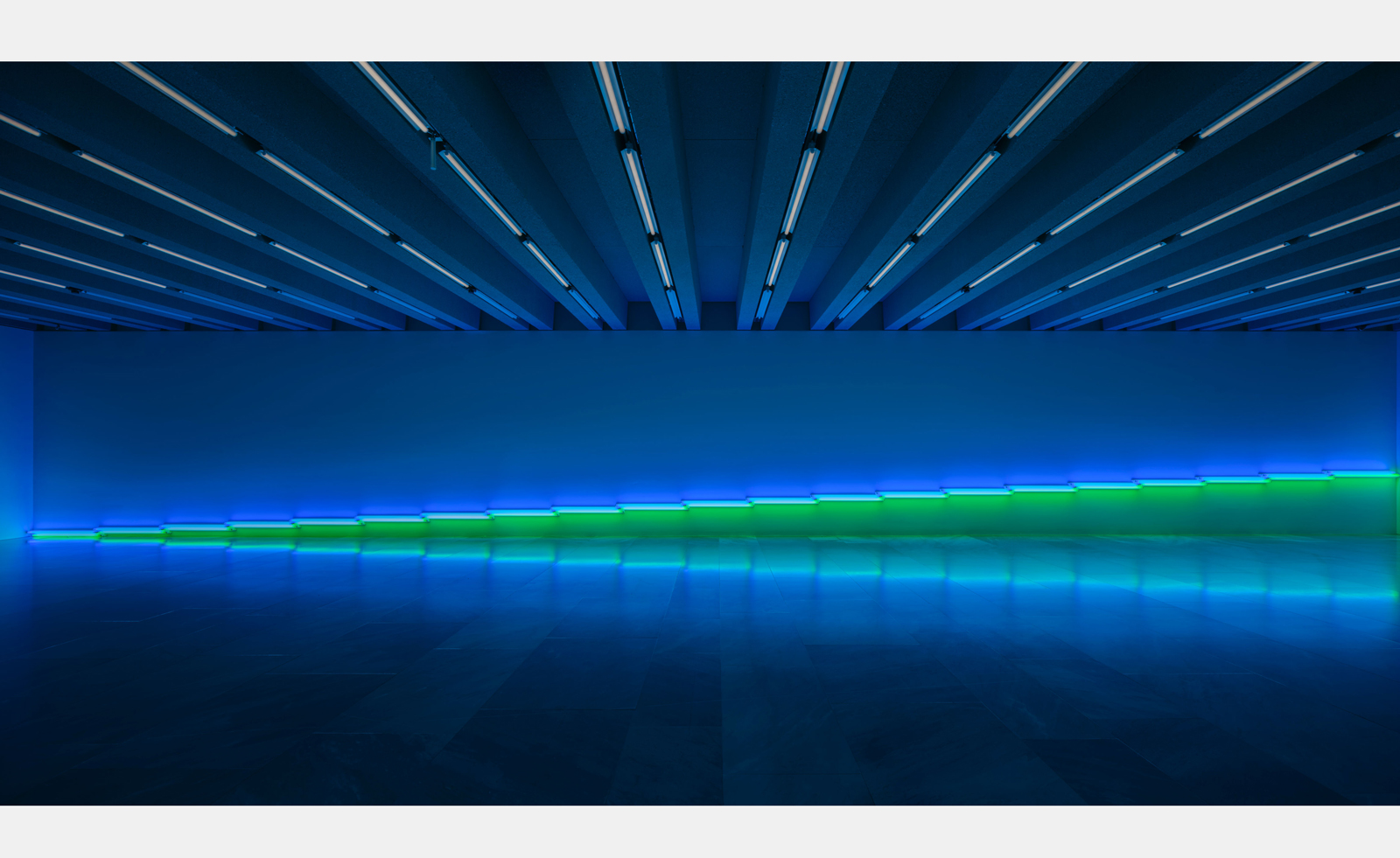

Dan Flavin, Untitled (to Barnett Newman) one, 1971

A work dedicated to McGovern is displayed in a room with Flavin’s preparatory drawings, instructions for assembling editions of the work and a collection of drawings by Swiss Renaissance mercenary, goldsmith and artist Urs Graf, by whom Flavin was fascinated and inspired.

We also see Flavin stretch his concept to the limit with his large-scale ‘barrier’ work Untitled (to you, Heiner, with admiration and affection), 1973, for the German dealer Heiner Friedrich. It spans an entire room, with fluorescent lights cubes so vivid the colours in the next room are altered. This effect of the light, with the colours depending on what else is in the room, and the colour of the light shifting according to the time of day and the location, is another aspect of the work. Some of the lights produce colour fields, some colours combine and others cast a light that appears to repel those thrown around it.

Dan Flavin, New York, 1970

Perhaps the most famous work in the show is Untitled (to Donald Judd the colorist) 1-5, 1987, five T-shaped lights in combinations of yellow, pink, green, red and blue that turn the room into a hum of anticipation evoking a disco. Flavin and Judd were good friends, and the latter’s son is named Flavin.

Dan Flavin’s work forms a selfie-takers’ paradise, but it also is part of the history of art, a key part of minimalism and highly influential in the history of light art and the use of neons that is now ubiquitous. This show is bathed in American history and allows for the man as well as the work, exploring his affection and attachment to those who surrounded and influenced him, also highlighting the work of his first wife. A fascinating artist who started out in seminary, Flavin’s self-obstructive obsessions have left an oeuvre for us to enjoy.

‘Dedications’ in Lights at Kunstmuseum Basel is on until 18 August 2024

Amah-Rose Abrams is a British writer, editor and broadcaster covering arts and culture based in London. In her decade plus career she has covered and broken arts stories all over the world and has interviewed artists including Marina Abramovic, Nan Goldin, Ai Weiwei, Lubaina Himid and Herzog & de Meuron. She has also worked in content strategy and production.

-

Extreme Cashmere reimagines retail with its new Amsterdam store: ‘You want to take your shoes off and stay’

Extreme Cashmere reimagines retail with its new Amsterdam store: ‘You want to take your shoes off and stay’Wallpaper* takes a tour of Extreme Cashmere’s new Amsterdam store, a space which reflects the label’s famed hospitality and unconventional approach to knitwear

By Jack Moss

-

Titanium watches are strong, light and enduring: here are some of the best

Titanium watches are strong, light and enduring: here are some of the bestBrands including Bremont, Christopher Ward and Grand Seiko are exploring the possibilities of titanium watches

By Chris Hall

-

Warp Records announces its first event in over a decade at the Barbican

Warp Records announces its first event in over a decade at the Barbican‘A Warp Happening,' landing 14 June, is guaranteed to be an epic day out

By Tianna Williams

-

Switzerland’s best art exhibitions to see in 2025

Switzerland’s best art exhibitions to see in 2025Art fans, here’s your bucket list of the standout exhibitions to see in Switzerland in 2025, exploring compelling themes and diverse media

By Simon Mills

-

Out of office: what the Wallpaper* editors have been doing this week

Out of office: what the Wallpaper* editors have been doing this weekA snowy Swiss Alpine sleepover, a design book fest in Milan, and a night with Steve Coogan in London – our editors' out-of-hours adventures this week

By Bill Prince

-

‘Happy birthday Louise Parker II’: enter the world of Roe Ethridge

‘Happy birthday Louise Parker II’: enter the world of Roe EthridgeRoe Ethridge speaks of his concurrent Gagosian exhibitions, in Gstaad and London, touching on his fugue approach to photography, fridge doors, and his longstanding collaborator Louise Parker

By Zoe Whitfield

-

What to see at Art Basel 2024, as the fair arrives at its hometown

What to see at Art Basel 2024, as the fair arrives at its hometownArt Basel 2024, the fair of all fairs, runs 13-16 June, with 285 international exhibitors and a long list of side shows and projects

By Osman Can Yerebakan

-

Space for My Body: Anu Põder’s retrospective opens in Switzerland

Space for My Body: Anu Põder’s retrospective opens in SwitzerlandEstonian artist Anu Põder is celebrated by Switzerland’s Muzeum Susch in an exhibition curated by Cecilia Alemani

By Hannah Silver

-

Bally Foundation’s new Lake Lugano headquarters is an art-filled paradise

Bally Foundation’s new Lake Lugano headquarters is an art-filled paradiseThe Bally Foundation inaugurates its new headquarters in a 1930s villa overlooking the majestic Lake Lugano, Switzerland with the group show ‘Un Lac Inconnu’ (An Unknown Lake)

By Hili Perlson

-

Supergraphics pioneer Barbara Stauffacher Solomon: ‘Sure, make things big – anything is possible'

Supergraphics pioneer Barbara Stauffacher Solomon: ‘Sure, make things big – anything is possible'94-year-old graphic designer Barbara Stauffacher Solomon talks radical typography, motherhood, and her cool welcome for St Moritz

By Jessica Klingelfuss

-

Fluffy bunnies meet office politics in Nicolas Haeni’s photo series

Fluffy bunnies meet office politics in Nicolas Haeni’s photo seriesTo mark the Year of the Rabbit, we return down the rabbit hole of Swiss photographer Nicolas Haeni’s photography series, where mischievous bunnies infiltrate the humdrum of corporate life

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith