Esther Mahlangu’s first retrospective features the iconic BMW 525i Art Car

Esther Mahlangu showcases ‘Then I knew I was good at painting’ at the Iziko Museums of South Africa in Cape Town

In 1991, a year following the release of Nelson Mandela from prison, Esther Mahlangu painted the BMW 525i Art Car with her distinctive Ndebele designs and bold colours. She was the first woman, and the first African artist, to contribute to the celebrated project, joining artists from the canon – Alexander Calder, David Hockney, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg, Frank Stella and Andy Warhol.

In the townships, where Mahlangu grew up and lives today, these sportier BMW models were nicknamed ‘Igusheshe’ to roughly mean ‘it grinds’ in Zulu as a note to their distinctive engine note. These fast cars were aspirational products, admired by all and certainly not attainable for most. ‘I painted the car like a wall, and for the Ndebele people, if you begin to paint a wall, it means you’re announcing either a wedding or a celebration,’ recalls Mahlangu.

‘Then I knew I was good at painting: Esther Mahlangu’

The BMW 525i Art Car takes centre stage at ‘Then I knew I was good at painting: Esther Mahlangu’, the artist’s first retrospective, held at the Iziko Museums of South Africa in Cape Town (it’s also referenced in the car maker’s Frieze LA 2024 reveal, the BMW i5 Flow NOSTOKANA). ‘Back then, to see a BMW painted in Ndebele design was a huge thing for our communities,’ explains the exhibition curator Nontobeko Ntombela. ‘For Mahlangu to have turned this car into her art suddenly highlights these aspirations in ways that co-opt it between the African and Western.’ She believes the Mahlangu BMW Art Car encapsulates the tensions that exist in South Africa – the tensions of the modern and rural, technological and the handmade.

Mahlangu is a national treasure. Almost 90, with her vibrant traditional Ndebele dress, her presence is as striking as her art. Born in 1935 in Middelburg, in the Mpumalanga province of South Africa, her mother and grandmother taught the young Mahlangu the art of Ndebele mural painting.

Practised by the Ndebele people (primarily based in South Africa and Zimbabwe), Ndebele art is typically hand-painted using natural pigments, with acrylic paints adopted by contemporary artists such as Mahlangu for their wider colour choice and longevity. The vibrant geometric motifs associated with the art are painted on various surfaces, on walls, houses, clothing, pottery and textiles. And they offer both aesthetic and cultural readings with pattern and colour carrying symbolism, often reflecting the cultural identity, social status, and spiritual beliefs within the community.

‘I would continue to paint on the house when they left for a break. When they came back, they would say: What have you done, child? Never do that again. After that, I started drawing on the back of the house, and slowly, my drawings got better and better until they finally asked me to come back to the front of the house. Then I knew I was good at painting,’ wrote Mahlangu, in a quote that has informed the exhibition title.

Mahlangu’s work is rooted in the centuries-long tradition of Ndebele art, yet hers is a unique approach to colour and shape that flows seamlessly between indigenous designs and contemporary art. She was one of the first to translate the Ndebele style of mural painting to canvas. Chicken feathers are her brushes of choice (although some of her latter wall-size artworks do involve paintbrushes), and instead of making preliminary sketches for her designs, Mahlangu works straight from the imagination. And she refrains from working in a conventional studio, preferring the more modest setting of her hometown, often laying out the canvases on the floor, and employing her family members as studio assistants.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Mahlangu’s precise geometric shapes and abstract forms are created without the aid of rulers or masking tape, and the thick black lines that are a defining feature of her work echo traditional Ndebele beadwork. There are other signals that set her work apart: motifs of the razorblade for cutting hair appears throughout her work, as do streetlamps, painted at a time when electricity was not available to her community.

‘Seeing these appear in her murals shifts the so-called traditional practice,’ says Ntombela. The curator wanted to capture Mahlangu’s sense of agency, tell her story from her lens: a fearless artist with self-belief at a time when the art world was not open to her. ‘Naming the exhibition after a childhood scenario is important as it is testimony to Mahlangu’s defying spirit and foresight,’ she explains. ‘It is radical that Mahlangu would see herself as an artist when only ten years old, and in the 1940s South Africa. It tells us about her self-belief, how she understood her significance and talent.’

Mahlangu first came to the attention of an international audience in the group show ‘Magiciens de la Terre’ held at the Centre Pompidou in 1989. In Paris, Mahlangu created a reconstruction of her house to demonstrate the possibility of bringing her design onto an artificial surface, as well as transporting her culture into a global context. For the artist, it was, and is, critical to place Ndebele art into the Western art canon as a way of preserving its history. To show the significance of this moment, the Iziko Museums features a scaled-down model of the Pompidou house.

Most striking, perhaps, are her wall-size canvas works created from the early 1990s, which hang in Iziko Museums’ final gallery. Canvas allowed Mahlangu to explore colour and design in new ways. Crucially, it made it possible for her work to travel and enter private collections, where most of her artwork was sourced for this show.

Exhibitions of Ndebele art can often be about the collective, leaving out the individual voice. Curator Ntombela, a lecturer at Wits School of Arts in Johannesburg, believes this may explain why South Africa has struggled to show Mahlangu’s work and why her artworks are mainly collected outside of the country. She says there is an interesting relationship between South Africans and Esther Mahlangu. ‘This is a person who is celebrated around the world but we see as doing something that is everyday. In dealing with this I had to do a lot of un-learning and write a story from a contemporary position, and from a different kind of art historical engagement.’

Ntombela believes Mahlangu’s approach shows how indigeneity can lead to generative, expansive and creatively exciting art; how practices of culture can embody a modernist approach and intellectual processes of making. ‘She doesn’t become the sole representative of an otherwise collective or communal culture. Rather, she inhabits a complex nexus between tradition and modernity in all its constant reinterpretations. It is with this unique practice that Mahlangu begins to expand and trouble the canon and its conventions,’ she says.

‘Painting has always been a part of me,’ writes Mahlangu. ‘I cannot separate it from myself, and neither would I want to.’

‘Then I Knew I Was Good at Painting: Esther Mahlangu’, supported by the BMW Group, will be at the Iziko Museums of South Africa until 11 August 2024, after which it will begin a global tour, stopping first at the Wits Art Museum in Johannesburg before moving to the US in early 2026. BMW is working with Esther Mahlangu on a project to be revealed at Frieze LA 2024.

A writer and editor based in London, Nargess contributes to various international publications on all aspects of culture. She is editorial director on Voices, a US publication on wine, and has authored a few lifestyle books, including The Life Negroni.

-

Formafatal ventures deep into the Costa Rican jungle with Studio House, a spectacular retreat

Formafatal ventures deep into the Costa Rican jungle with Studio House, a spectacular retreatSet high on a forested hillside, the Studio House has far-reaching ocean views yet is completely integrated into its site

-

Peek inside Madrid’s best-kept art secret

Peek inside Madrid’s best-kept art secretSolo’s labyrinthine new art space in Madrid presents a surreal opportunity for exploring contemporary art and architecture

-

A lush Bengaluru villa is a home that acts as a vessel for nature

A lush Bengaluru villa is a home that acts as a vessel for natureWith this new Bengaluru villa, Purple Ink Studio wanted gardens tucked into the fabric of the home within this urban residence in India's 'Garden City'

-

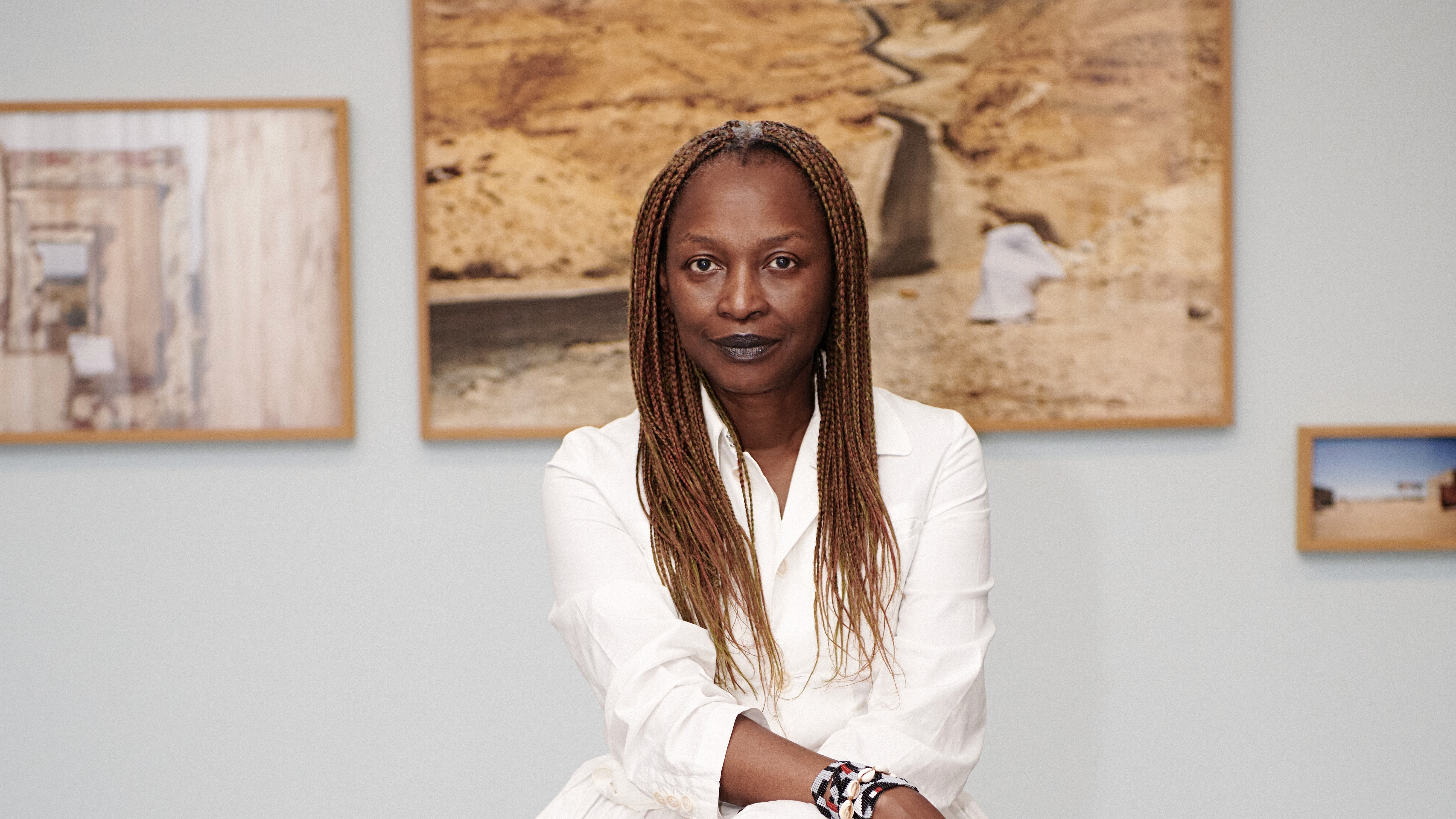

Remembering Koyo Kouoh, the Cameroonian curator due to lead the 2026 Venice Biennale

Remembering Koyo Kouoh, the Cameroonian curator due to lead the 2026 Venice BiennaleKouoh, who died this week aged 57, was passionate about the furtherance of African art and artists, and also contributed to international shows, being named the first African woman to curate the Venice Biennale

-

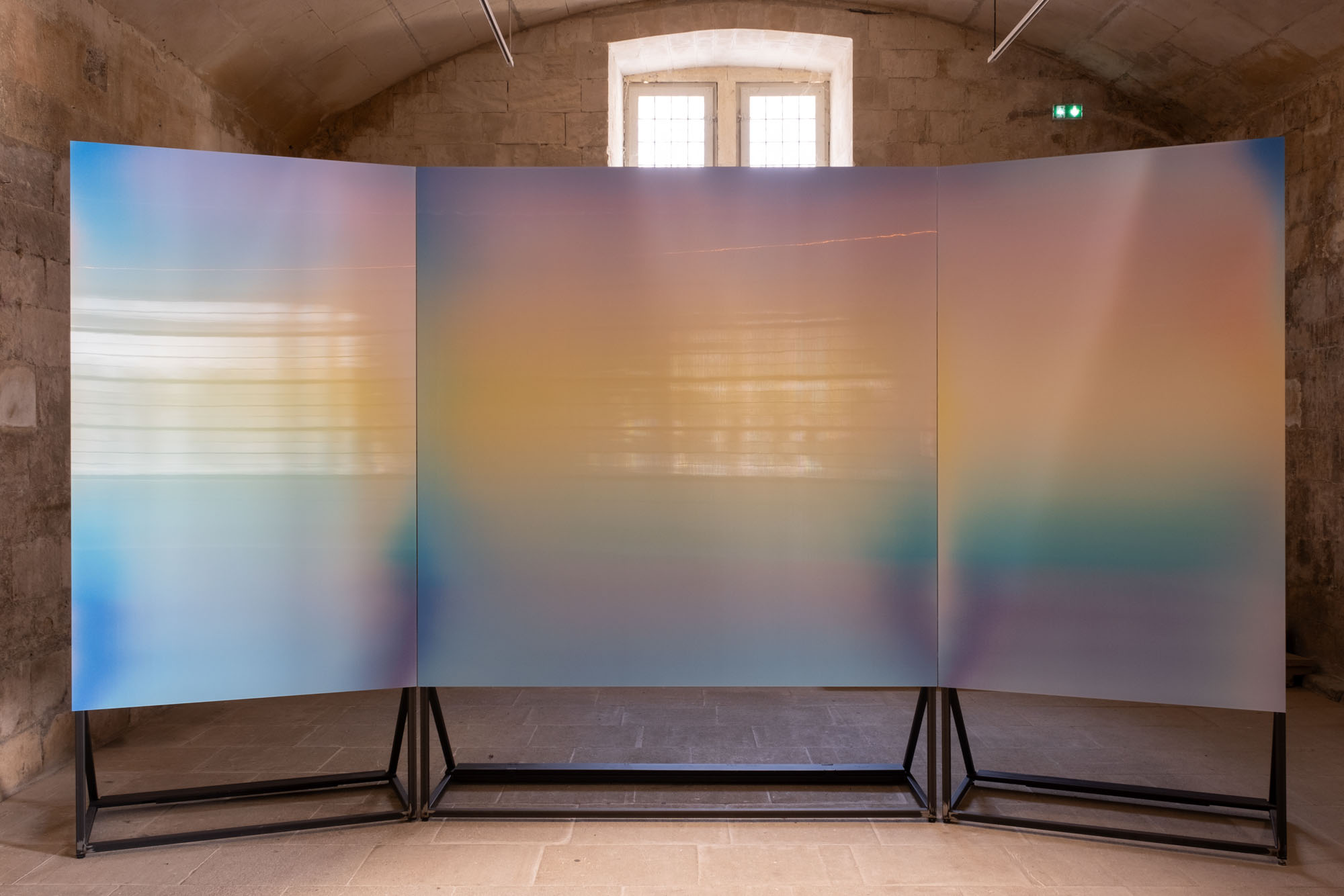

‘Who has not dreamed of seeing what the eye cannot grasp?’: Rencontres d’Arles comes to the south of France

‘Who has not dreamed of seeing what the eye cannot grasp?’: Rencontres d’Arles comes to the south of FranceLes Rencontres d’Arles 2024 presents over 40 exhibitions and nearly 200 artists, and includes the latest iteration of the BMW Art Makers programme

-

Es Devlin and BMW reveal hydrogen-fuelled collaboration at Art Basel 2024

Es Devlin and BMW reveal hydrogen-fuelled collaboration at Art Basel 2024Es Devlin and BMW celebrate the potential of hydrogen power in installations unveiled at Art Basel 2024, including a take on the BMW iX5 Hydrogen

-

Zanele Muholi celebrates South Africa’s Black LGBTI communities in LA and London

Zanele Muholi celebrates South Africa’s Black LGBTI communities in LA and LondonZanele Muholi's portraits and sculptures are currently on show at Southern Guild Los Angeles and the Tate Modern, London

-

Julie Mehretu is the latest artist to transform a BMW racing car into a dynamic artwork

Julie Mehretu is the latest artist to transform a BMW racing car into a dynamic artworkThis is the 20th BMW Art Car, a BMW M Hybrid V8 racecar that’ll take to the track at Le Mans with a livery created by artist Julie Mehretu

-

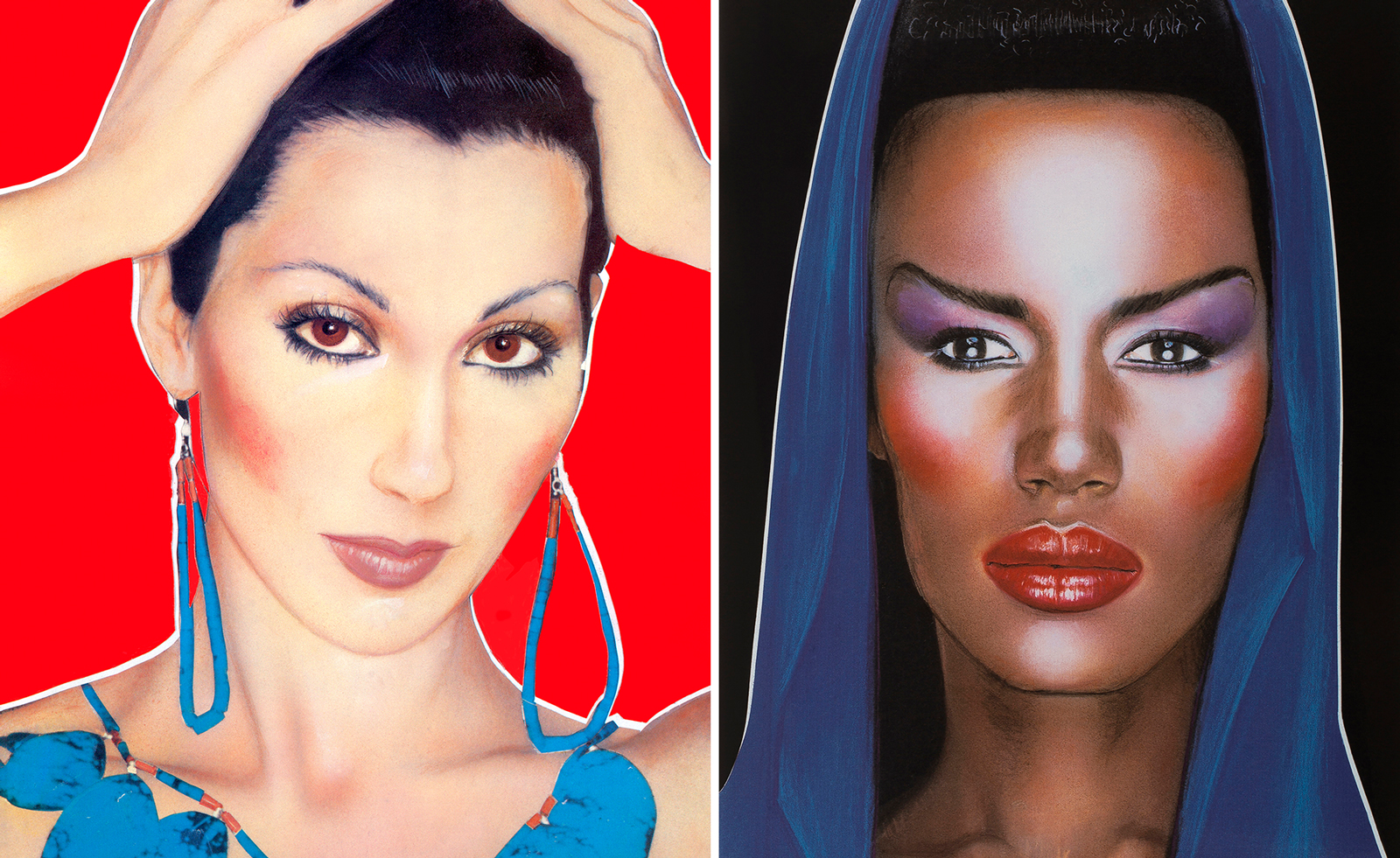

Richard Bernstein's bold covers for Andy Warhol's 'Interview' magazine go on show in New York

Richard Bernstein's bold covers for Andy Warhol's 'Interview' magazine go on show in New YorkBernstein's portraits of stars, including Cher, Stevie Wonder, Fran Lebowitz, Mick Jagger and Grace Jones can be seen at Neuehouse, Manhattan.

-

Alex Israel uses BMW technology for AI-powered video installation at Art Basel Miami Beach 2023

Alex Israel uses BMW technology for AI-powered video installation at Art Basel Miami Beach 2023Alex Israel’s 'REMEMBR' at Art Basel Miami Beach 2023 uses AI technology to curate and choreograph a visitor’s phone camera content into a video installation across seven screens

-

Now Gallery presents the vibrant culture of ‘A Young South Africa’ captured through the lens

Now Gallery presents the vibrant culture of ‘A Young South Africa’ captured through the lensNow Gallery’s ‘A Young South Africa, Human Stories’ showcases six inspiring photographers for the 2023