From Rembrandt to Warhol, a Paris exhibition asks: what do artists wear?

‘The Art of Dressing – Dressing like an Artist’ at Musée du Louvre-Lens inspects the sartorial choices of artists

Three years ago, when Annabelle Ténèze was director of Les Abattoirs in Toulouse, she was working on a show on the sculptor and painter Niki de Saint Phalle. “I was amazed by how much she was on television and that her voice in the public sphere was very much heard,” said the curator, now Director of Musée du Louvre-Lens. We were talking a few days after the opening of her first show at the museum ‘The Art of Dressing – Dressing like an Artist’. A photograph of de Saint Phalle aiming a gun in a black velvet jumpsuit with white lace, from her film ‘Daddy’ (1972), was staring at me. She was lucky to get a look at the artist’s closet back then, reminisced Ténèze, which made her realise de Saint Phalle’s eccentric dressing also carried over into her private life. Constantly wondering about artistic self-fashioning, even after Les Abattoirs to her current position, met its final form in the vaulted halls of the museum.

Constance Mayer, Autoportrait, entre 1795 et 1801, huile sur toile, Boulogne-Billancourt, Bibliothèque Paul-Marmottan_Académie des beaux-arts, Institut de France © Bibliotheque Marmottan, Paris / Bridgeman Images

Last year Charlie Porter came out with ‘What Artists Wear’ and Ténèze reads it a lot, she admits. “He says that he’s a fashion critic, even while he’s with contemporary artists all the time, he hadn’t made that connection between them and their sartorial choices earlier,” she reflected, “It can happen to us all the time.”

Tracing artistic motivations behind personal style reflected in artworks – particularly self-portraits – is to understand what the artist desired to be portrayed as, rather than what they actually wore in reality. Thus, much importance is given to Rembrandt and his continuous self-fashioning through more than a hundred self-portraits. According to the seventeenth century biographer Arnold Houbraken, Rembrandt could spend a day or two arranging a turban until he was satisfied. “In a way Rembrandt is the Cindy Sherman of the 17th century,” laughed Ténèze, “He’s always changing according to social archetypes. I always say that someone needs to recreate all the clothes Rembrandt used in his self-portraits.” In one of them, the artist – then young – painted himself wearing an out-of-fashion black beret, possibly to align himself with past masters like Raphael or Titian, whose self-portraits featured a similar coloured beret.

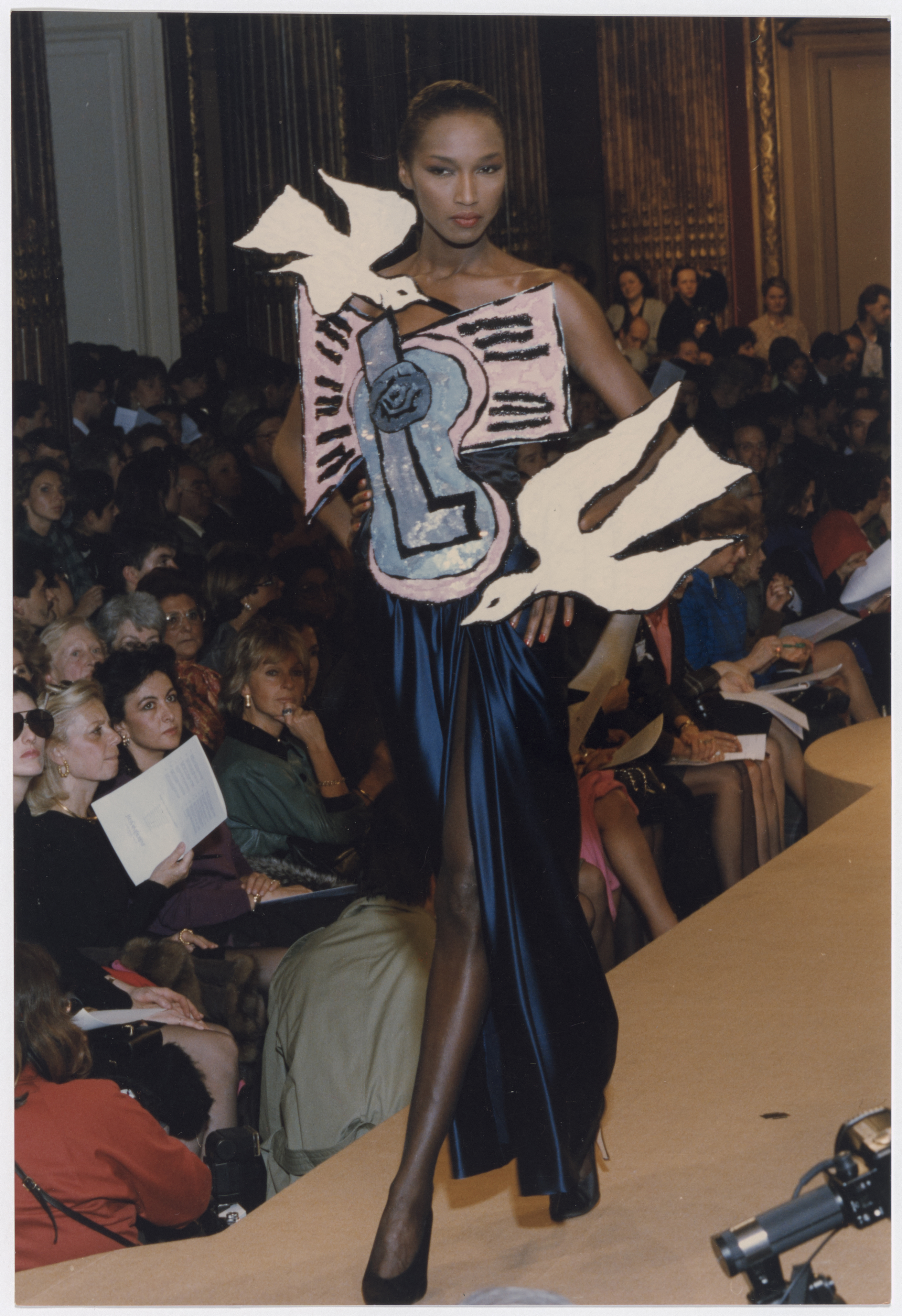

Yves Saint Laurent, Robe du soir, hommage à Georges Braque, collection printemps-été 1988, Paris, Musée Yves Saint Laurent © Yves Saint Laurent © droits réservés

Rembrandt was a precursor in what would become a tradition of ostentatiously attired artists, who in their self-portraits painted themselves as richly adorned as their clients. A portrait of his contemporary Charles Le Brun in his studio, by Nicolas de Largillière swathes the former in thick layers of what seems to be orange velvet overcoat and an embellished ochre waistcoat with silky white ruffles at the sleeves. Although he’s surrounded by his works, Le Brun looks appropriately dressed to be a patron himself. Moreover, he wears bright red pointed mules – not quite comfortable for studio work. Another of Rembrandt’s contemporaries Michael Sweerts’ ‘The Artist’s Studio with a Seamstress’ donned a young apprentice – surrounded by a pile of practice sculptures – in a long ochre yellow overcoat with brown trousers emblematic of a student, the practical colours reflective of dirt and working with his hands. In contrast, a self-portrait of Sweerts shows himself working beyond the confines of a studio, under the open sky, in a black doublet and white shirt, revealing his collar and sleeves – a black ribbon tied into a bow under his right hand.

George Achille-Fould, Rosa Bonheur dans son atelier, 1893, huile sur toile, Bordeaux, Musée des Beaux-Arts © Mairie de Bordeaux / F. Deval

Another of the many – now humorous – ways through while male artists were pushing forth their elevated social status was through painting Saint Luke, one of the four evangelists of the New Testament, whom artists claimed as their patron saint from as early as the 6th century. A 1603 work by Nicolas de Hoey in the gallery shows Luke painting the Virgin Mary – his contemporary, but intriguingly, she was sitting for him in his studio. Moreover, the artist’s own facial features had been painted on the patron saint, uplifting himself while giving legitimacy to the profession of the artist.

Nicolas de Hoey, Saint Luc peignant la Vierge, 1603, huile sur bois, dépôt de la commune de Moloy - Côte d'Or au Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon © Direction des Musées de Dijon / François Jay

But what of women? Both Porter and Ténèze are extremely aware of male domination over female fashion, particularly now with a majority of male creative directors in womenswear and the owners of the two biggest luxury conglomerates being both men, profiting from what women spend. A self-portrait of Constance Mayer shows her sitting at a table, in a white dress fitted under the bust, the thin fabric clinging to her skin. Painted in between 1795 to 1801, this near-boudoir style arose due to the identification of the archaeological site of Pompeii in 1748, propelling a Roman revival. The French revolution broke down restrictive dress codes, and dresses became simpler and followed the natural contours of the body, their whiteness referring to ancient statues. As the imported Bengal cotton hid nothing, women were directed to wear cotton underwear, but many women like the writer Fortunée Hamelin did not abide by such rules – one of her most outrageous garments in Parisian society being a transparent chiffon gauze gown with a slit up the thigh, over flesh-coloured underclothes – of course, that didn’t well with her husband. This style would stop once Napoleon arrived, even forcing his wife who followed this style, to abandon it. This style persists even today, in the ateliers of houses like Dior during Maria Grazia Chiuri’s era, a FW19 toga style dress with the cheeky graphic ‘Are Clothes Modern?’

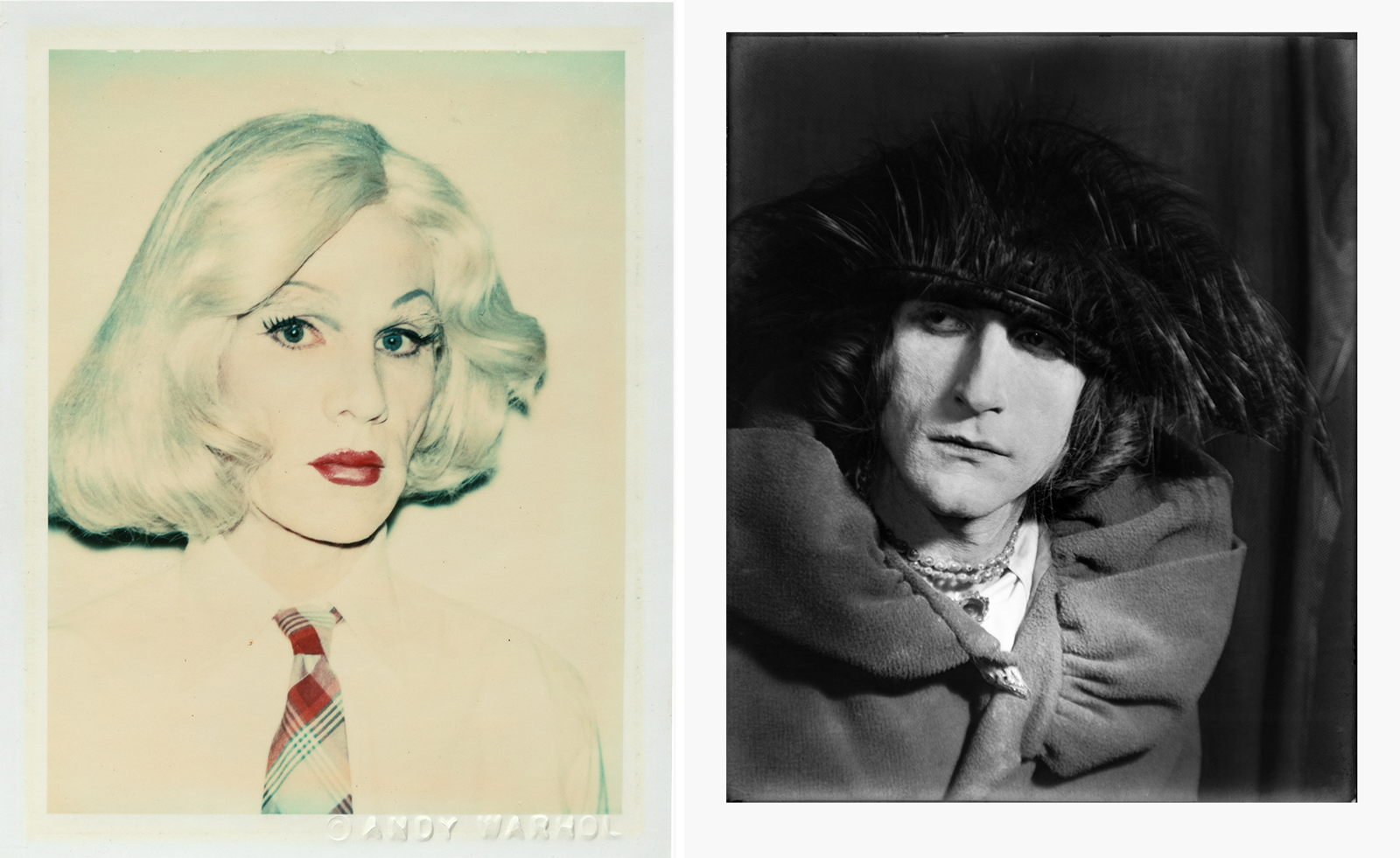

Andy Warhol leans on the fire escape at the Factory as Stephen Shore takes a photograph. He’s in the stereotypical French striped shirt – popularised as artistic-wear through photographs of Picasso in it in popular magazines earlier that century (“I’m sure he was not wearing it all the time,” said Ténèze wryly) – that hangs loosely around his nape, and what might possibly be his signature jeans. “Bohemians are a cliché,” said Ténèze, “If you look at the emoticon of the painter in your iPhone, it’s a bohemian in a white shirt and bow around their neck.” Before the 18th century, artist portraits simply wearing the shirt without any outerwear, was considered indecent – which is what artists gradually moved towards, almost reflecting the very basis of an artist’s work of transferring their internal thoughts into the external universe. It’s a certain kind of intimacy, this insight into the internal workings of their world.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

However, artists would move on from the shirt once it became associated with bourgeoise respectability in the twentieth century, to the working-class blouse. In the nineteenth century, artist Rosa Bonheur had already adopted that, after having to seek permission from the Paris police for “cross-dressing”. One of my favourite works in the exhibition is painted by Georges Achille-Fould – a female painter working under a pseudonym – where she depicted Bonheur in her atelier, painted lions. “She said to Rosa, ‘I want to paint the real you in the studio,’” said Ténèze, “The position of her legs are also very masculine – not one of a lady from the 19th century.” She seems to have paused in between that to look at us with fiery eyes, smiling defiantly in a blue work blouse and brown trousers. Bonheur has been depicted in other works by male artists – like her brother Auguste, who painted her in a dark green dress and a white collar, or Édouard Dubufe who donned her a black satin and velvet dress – quite impractical for painting – throwing an arm on a tame bull, holding a paintbrush. It’s an interesting dichotomy that Bonheur had to tread, as she’s seen wearing traditionally feminine clothing in family photographs, whereas the ones taken by her partner and heir Anna Klumpke, Bonheur has a hat in her hand, sometimes even a cane or cigarette – typically male accessories.

During World War I, Sonia Delaunay opened a boutique and after the war, she started creating her own fabrics, as some of her early illustrations of sculptural skirts and multiple patterned jackets, in the exhibition, reveal. It's interesting how artists were working through their own practice through clothes, like Basquiat only wearing Comme des Garcons suits, even while painting and staining them or Niki de Saint Phalle launching her own fragrance in New York – a midnight blue bottle topped off with a gold cap and two colourful intertwined snakes – the kind she often made in her sculptures – which apparently allowed her some financial freedom. She was great friends with then artistic director of Dior, Marc Bolan, who collected her work and created pieces for her, taking patterns from her work. Early in her New York practice, Yayoi Kusama launched her own fashion company working with the idea of nudity – she was terrified of sex – and wanted to work through that, by remaking what she, and many others, feared. It ultimately didn’t succeed commercially, but clearly her fascination with provoking unease through repetition has continued.

‘The Art of Dressing – Dressing like an Artist’ at Musée du Louvre-Lens until July 21 2025

Upasana Das is a freelance writer working on fashion, art and culture. She has written for NYT, Dazed, Interview Mag, Vogue India and Harper's among others.

-

Meet Lisbeth Sachs, the lesser known Swiss modernist architect

Meet Lisbeth Sachs, the lesser known Swiss modernist architectPioneering Lisbeth Sachs is the Swiss architect behind the inspiration for creative collective Annexe’s reimagining of the Swiss pavilion for the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025

By Adam Štěch

-

A stripped-back elegance defines these timeless watch designs

A stripped-back elegance defines these timeless watch designsWatches from Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels, Rolex and more speak to universal design codes

By Hannah Silver

-

Postcard from Brussels: a maverick design scene has taken root in the Belgian capital

Postcard from Brussels: a maverick design scene has taken root in the Belgian capitalBrussels has emerged as one of the best places for creatives to live, operate and even sell. Wallpaper* paid a visit during the annual Collectible fair to see how it's coming into its own

By Adrian Madlener