‘Mental health, motherhood and class’: Hannah Perry’s dynamic installation at Baltic

Hannah Perry's exhibition ’Manual Labour’ is on show at Baltic in Gateshead, UK, a five-part installation drawing parallels between motherhood and factory work

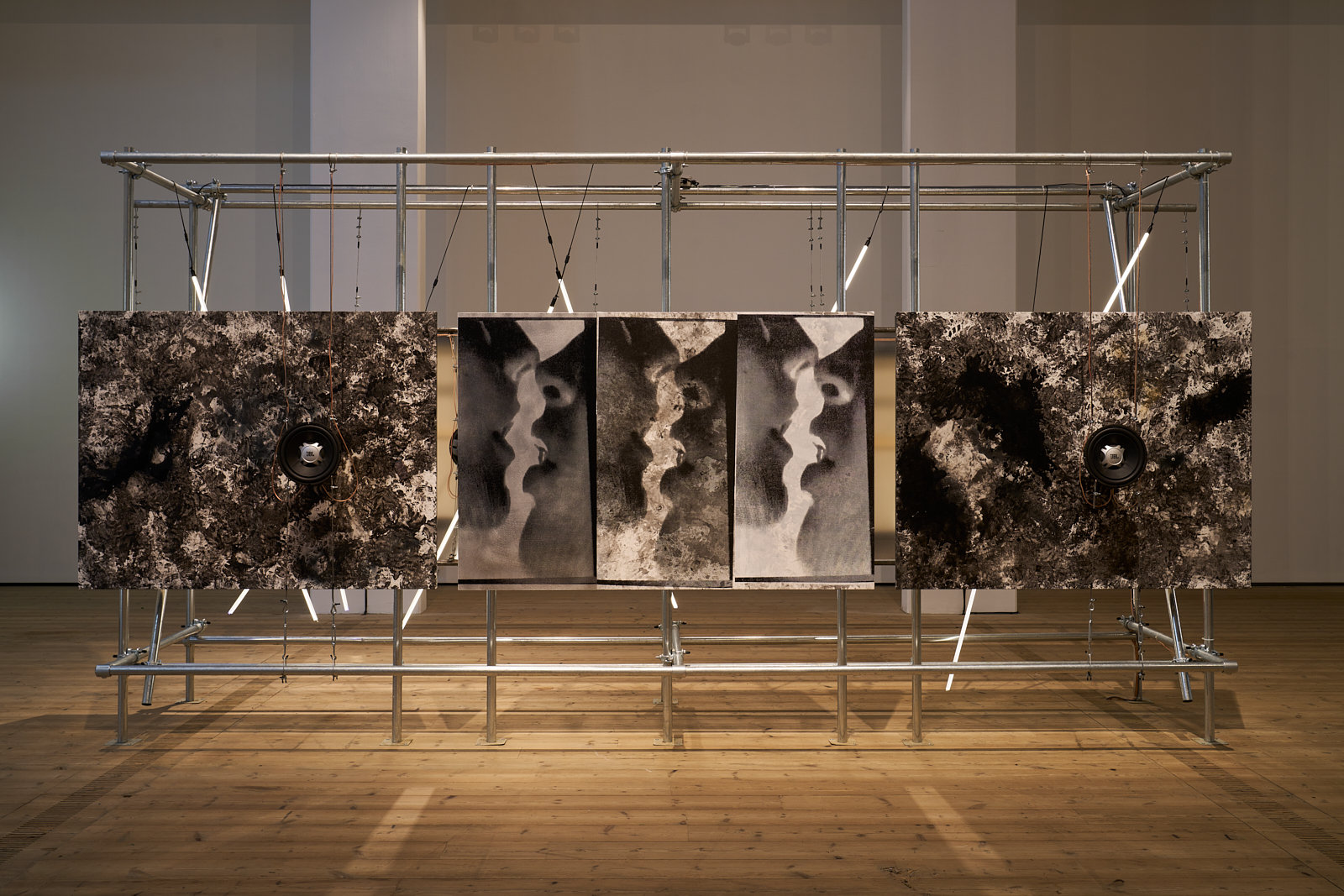

Hannah Perry’s dynamic installations explore the entangled relationship between labour, mental health, and physical endurance. The British artist is now showing ‘Manual Labour’ at Baltic in Gateshead, utilising industrial materials to draw parallels between factory work and the experience of motherhood.

The installation is made of five parts, which operate in relation to one another. It includes a 15-minute film shown on an expansive 6m screen, which is curved to mimic the shape of a diaphragm; 16 speakers emitting a surround-sound piece; and two hydraulic sculptural parts in the shape of pelvic bones that move together forcefully.

Hannah Perry presents ‘Manual Labour'

Hannah Perry, Manual Labour, 2024. Film still

'I’m really focusing on the interactions between mental health, motherhood and class,' the artist tells me, when we speak ahead of the show opening. She has long focused on the emotional toll of our fast-paced contemporary world, which often de-centres human wellbeing.

Her 2018 installation Gush, at London’s Somerset House, was a deeply emotional exploration of the impact of grief and trauma, following the suicide of her friend and collaborator Pete Morrow. Similarly, Manual Labour brings together personal experiences and universal social issues.

Hannah Perry, Manual Labour, installation view

'The hydraulic pelvis riffs on my older concepts of physical limitations and bodily violences,' she says. 'It’s about physical tensions, or being pushed to our limits, which is always connected with our mental capacities. Previous performance works, like Gush, have pushed the dancers to their limits.

‘In this show, I’m interested in where that idea intersects with the creative or destructive parts of giving birth. The other element in there is connected to social pressures. If your resources are limited, pregnancy and motherhood look very different. There is this historical demonisation of working-class women having lots of children. I find these particular intersections very interesting.'

Hannah Perry, Manual Labour, installation view

Hannah Perry, Manual Labour, 2024. Film still

The hydraulic sculpture includes steel and shock absorbers, bringing the weighty forms of factory floors together with the physical toil of birth. These parts are powerful and robust, evoking the might of the human body when pushed to its edge but also the intense pressure that it is expected to withstand.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

The video piece takes visitors inside a Serbian titanium factory, the largest of its kind in the world. It also features footage from a shoot in London, in which the artist at nine-months pregnant stood amongst a 360-degree set-up of mirrors. 'In the factory, there is this large, really aggressive machinery,' she says. 'There’s all this crashing, crushing, and traumatising the metal. Titanium is the strongest metal there is and it goes through all these processes. The working conditions are very tough, in these really hot rooms. In the work, this is offset against the pregnant body.'

Hannah Perry, Manual Labour, installation view

Hannah Perry, Manual Labour, 2024. Film still

Factory labour, like birth and early motherhood, tends to happen out of sight. We might see the final result of the factory-made item and think little of the work that went into it.

Similarly, the physical and emotional realities of motherhood have often remained a taboo subject, left largely unseen and therefore undervalued. In this work, Perry wrestles with the trap of domestic labour.

Hannah Perry, Manual Labour, 2024. Film still

'When I was on some kind of maternity leave, I felt like I didn’t value my role in the home,' she considers. 'I valued my self and economic worth in the male-dominated professional world more.

‘As women we should be able to do it all, but that brings with it a lot of pressure; physically and mentally you do need this grace period to recover after giving birth. We’ve worked hard to get out of this prescribed role of domesticity but it’s now kind of come full circle in that it can be difficult to value that labour at all.'

Hannah Perry, Manual Labour, 2024. Film still

Perry’s work does not offer simple answers, but highlights the messily entangled nature of labour with so many other social and bodily concerns. She shows the human form as both tough and traumatised, its energy often lost to a world that makes little distinction between the worth of human life and economic gain.

‘Hannah Perry, Manual Labour’ is at the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, UK, until 16 March 2025 baltic.art

Emily Steer is a London-based culture journalist and former editor of Elephant. She has written for titles including AnOther, BBC Culture, the Financial Times, and Frieze.

-

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressing

All-In is the Paris-based label making full-force fashion for main character dressingPart of our monthly Uprising series, Wallpaper* meets Benjamin Barron and Bror August Vestbø of All-In, the LVMH Prize-nominated label which bases its collections on a riotous cast of characters – real and imagined

By Orla Brennan

-

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationship

Maserati joins forces with Giorgetti for a turbo-charged relationshipAnnouncing their marriage during Milan Design Week, the brands unveiled a collection, a car and a long term commitment

By Hugo Macdonald

-

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craft

Through an innovative new training program, Poltrona Frau aims to safeguard Italian craftThe heritage furniture manufacturer is training a new generation of leather artisans

By Cristina Kiran Piotti

-

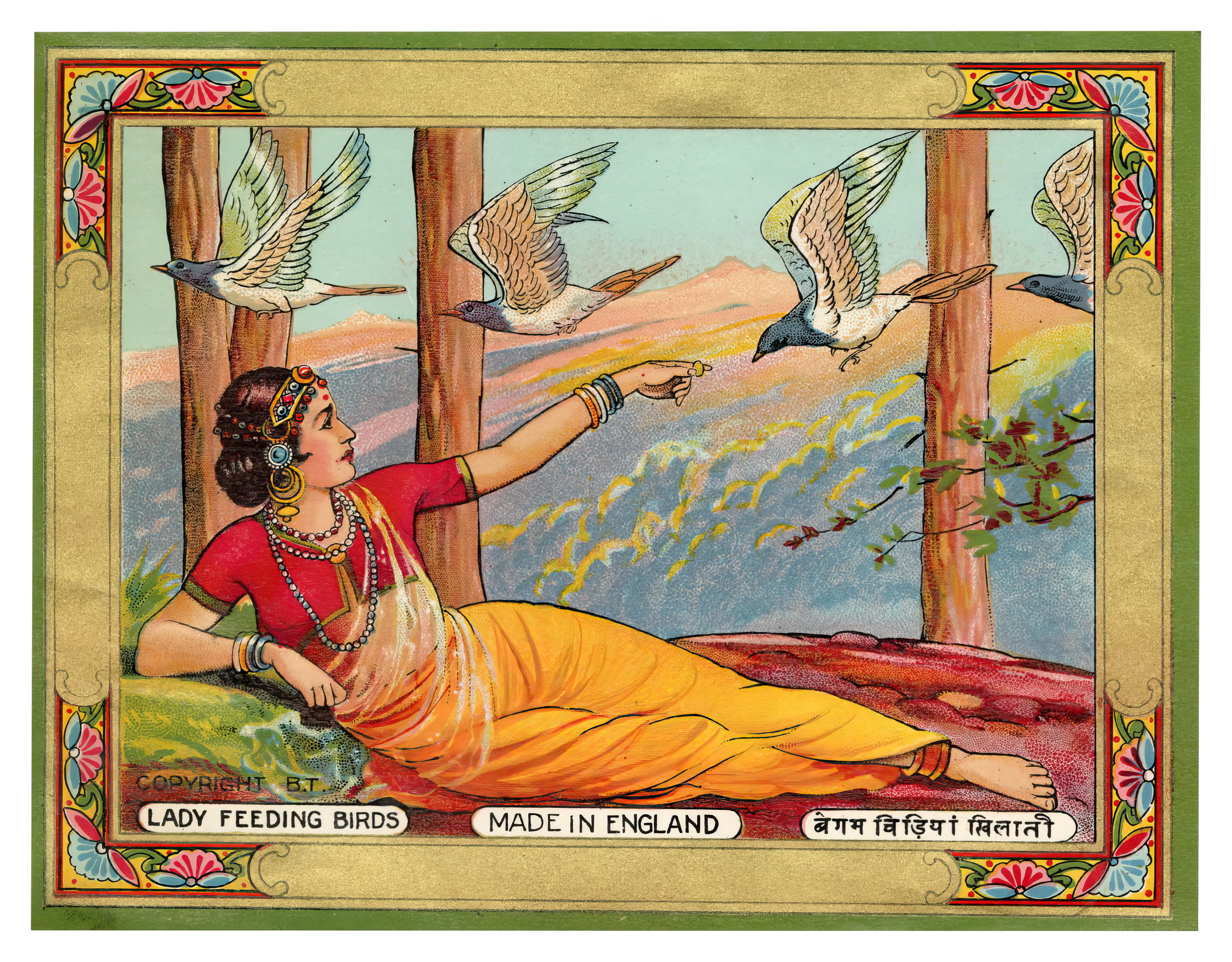

The art of the textile label: how British mill-made cloth sold itself to Indian buyers

The art of the textile label: how British mill-made cloth sold itself to Indian buyersAn exhibition of Indo-British textile labels at the Museum of Art & Photography (MAP) in Bengaluru is a journey through colonial desire and the design of mass persuasion

By Aastha D

-

From counter-culture to Northern Soul, these photos chart an intimate history of working-class Britain

From counter-culture to Northern Soul, these photos chart an intimate history of working-class Britain‘After the End of History: British Working Class Photography 1989 – 2024’ is at Edinburgh gallery Stills

By Tianna Williams

-

Surrealism as feminist resistance: artists against fascism in Leeds

Surrealism as feminist resistance: artists against fascism in Leeds‘The Traumatic Surreal’ at the Henry Moore Institute, unpacks the generational trauma left by Nazism for postwar women

By Katie Tobin

-

From activism and capitalism to club culture and subculture, a new exhibition offers a snapshot of 1980s Britain

From activism and capitalism to club culture and subculture, a new exhibition offers a snapshot of 1980s BritainThe turbulence of a colourful decade, as seen through the lens of a diverse community of photographers, collectives and publications, is on show at Tate Britain until May 2025

By Anne Soward

-

Jasleen Kaur wins the Turner Prize 2024

Jasleen Kaur wins the Turner Prize 2024Jasleen Kaur has won the Turner Prize 2024, recognised for her work which reflects upon everyday objects

By Hannah Silver

-

Peggy Guggenheim: ‘My motto was “Buy a picture a day” and I lived up to it’

Peggy Guggenheim: ‘My motto was “Buy a picture a day” and I lived up to it’Five years spent at her Sussex country retreat inspired Peggy Guggenheim to reframe her future, kickstarting one of the most thrilling modern-art collections in history

By Caragh McKay

-

Please do touch the art: enter R.I.P. Germain’s underground world in Liverpool

Please do touch the art: enter R.I.P. Germain’s underground world in LiverpoolR.I.P. Germain’s ‘After GOD, Dudus Comes Next!’ is an immersive installation at FACT Liverpool

By Will Jennings

-

‘Regeneration and repair is a really important part of how I work’: Bharti Kher at Yorkshire Sculpture Park

‘Regeneration and repair is a really important part of how I work’: Bharti Kher at Yorkshire Sculpture ParkBharti Kher unveils the largest UK museum exhibition of her career at Yorkshire Sculpture Park

By Will Jennings