Don’t miss: Hayv Kahraman intertwines colonialism and botany in London

Artist Hayv Kahraman draws parallels between colonial botany and her experiences as an Iraqi refugee transplanted into Europe, at Pilar Corrias in London

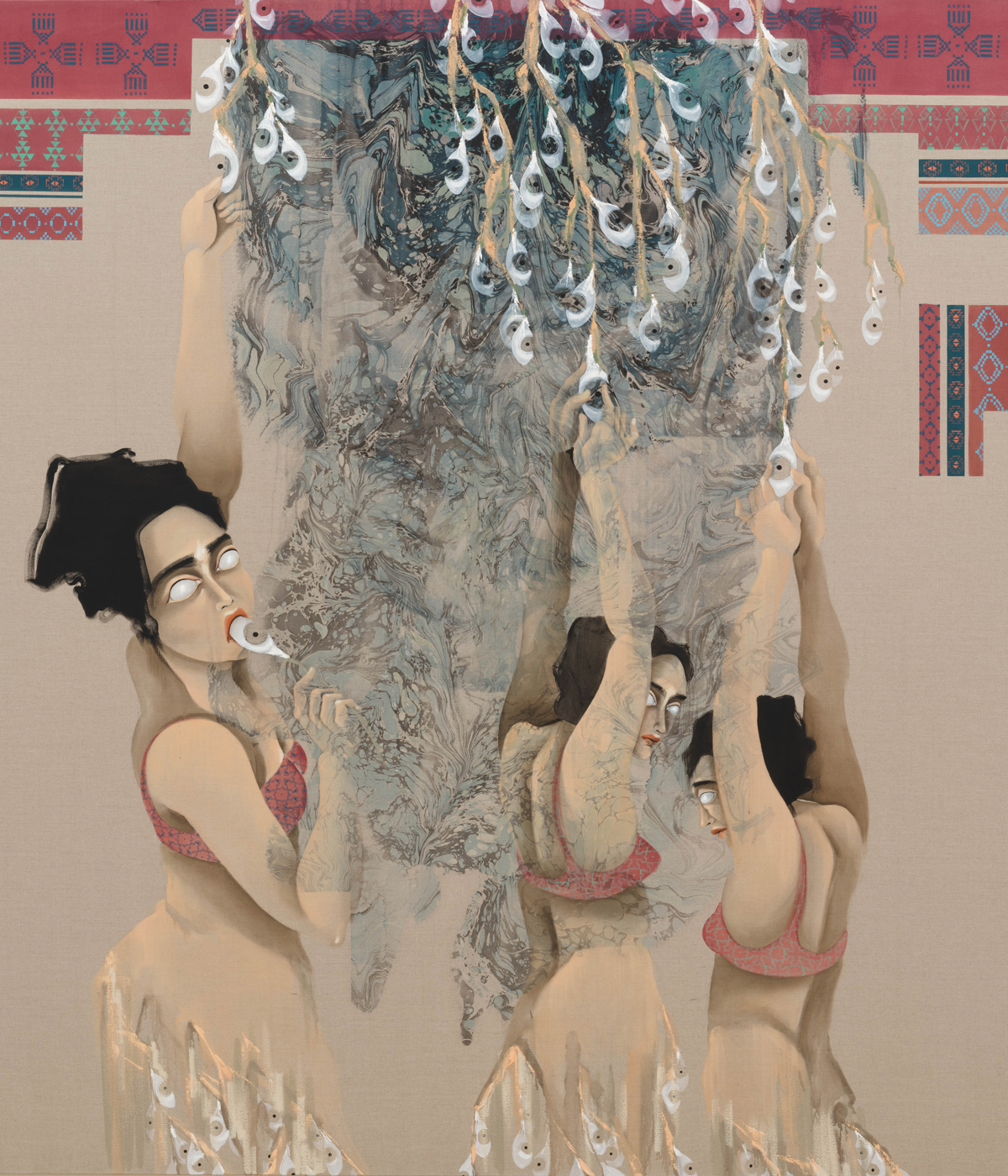

As an Iraqi refugee growing up in Sweden, artist Hayv Kahraman absorbed the teachings of 18th-century Swedish biologist Carl Linnaeus. Famed for his habit of transporting plants from around the world into Europe and for his system of reclassifying them with genus and species names, in Latin, he and his colonialist experiments became an inextricable part of Swedish identity for Kahraman, who saw parallels with her struggles to assimilate in a new country. In artworks by Hayv, who is now based in Los Angeles, these botanical references become synonymous with the idea of the Other. The painted forms of figures become dreamlike symbols, juxtaposed against diaphanous, dreamlike clouds of marbling.

We talked to the artist about the story behind her works.

Hayv Kahraman on reframing the narrative at Pilar Corrias in London

Hayv Kahraman, Eye-dates, 2024

Wallpaper*: By considering the colonial implications in a single piece of work, you embrace a juxtaposition of artistic forms and cultural references. Can you tell us why Linnaeus' work was so clearly meriting attention for you?

Hayv Kahraman: When I started my schooling in Sweden, I was taught that Carl Linnaeus was a genius and a heroic figure. He was on the 100 Krona bill, and I remember visiting his herbarium in Uppsala during a school field trip. Linnaeus was a Swedish botanist who lived in the 18th century. His taxonomic contributions to the natural sciences by means of collecting plants from elsewhere, bringing them back to Europe and renaming them into his latinised binomial nomenclature, contributed to erasing the indigenous histories surrounding that plant. These colonial practices of renaming flowers and plants, a vocabulary that centered the white European heteronormative man (most famously Linnaeus) and propelled nationalistic, eugenic and nativist pulses into botany were crucial in the expansion of empire.

But what irked me the most as I was researching, was his incessant urge to ‘acclimatize’ certain plants to the Swedish climate, which of course utterly failed. I am here reminded of the potent assimilation process I underwent in Sweden as a newly arrived Iraqi refugee back in the 1990s. How I was taught to think like a ‘Swede’, to act like a ‘Swede’ in order to be worthy of staying in that country. And it is this feeling of indignation that fuelled the work. I needed to unpack his volatile legacy, and then find alternative ways of sensing the world in which hope can be found.

Hayv Kahraman, Generational Eyebrows, 2024

W*: By taking control of techniques with roots in other societies, such as marbling, how did you celebrate a new perspective, separate from the historical implications?

HK: My interest in marbling started when I went to the Huntington Library in California to actually see/open/touch/feel one of Linnaeus’ books, and as I flipped open the cover I saw a marbled front piece and knew that I needed to look into this art form. Marbling has a long history, starting in Japan, travelling to central and west Asia and then Europe. It was used in the Ottoman region on legal documents to prevent forgery. Historical implications aside, I found it fascinating that an art medium was used to prevent appropriation, that it's a mono print that cannot be duplicated/appropriated/forged because of its incredible unpredictability.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

What turned things for me personally, though, was when I actually started marbling and experimenting in my studio. I found the process incredibly therapeutic.

[Not] being concerned about how things will ‘look’/ how things will be ‘perceived’/how legible/ knowable the work will be – it allows me to not categorise, to not order things, to break away from that kind of thinking that I’ve been plagued by since I became a refugee in Europe. I found that there’s an acceptance that happens in this process. An acceptance of the flow and movement of life somehow. And as a survivor of domestic violence, relinquishing control can be incredibly difficult, but marbling feels freeing. As if paving a way to heal.

Installation view, ‘Hayv Kahraman: She has no name’, Pilar Corrias, London

W*: The works themselves marry these techniques with powerful proportions that make strong female figures central. How did your process inform this otherworldly narrative?

HK: The figure, the body, has always been a means for me to negotiate things around me. I studied ballet in Baghdad at a very young age and since then I’ve always composed choreographies of bodies in my mind. I think of the figures as snapshots in my paintings. They are caught in an act of performing something. A doing and an undoing of something. They’ve become my methodology to think through difficult topics, such as colonial botany in this instance.

'She Has No Name' is at Pilar Corrias, London, until 25 May 2024

Hannah Silver is the Art, Culture, Watches & Jewellery Editor of Wallpaper*. Since joining in 2019, she has overseen offbeat design trends and in-depth profiles, and written extensively across the worlds of culture and luxury. She enjoys meeting artists and designers, viewing exhibitions and conducting interviews on her frequent travels.

-

Put these emerging artists on your radar

Put these emerging artists on your radarThis crop of six new talents is poised to shake up the art world. Get to know them now

By Tianna Williams

-

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeks

Dining at Pyrá feels like a Mediterranean kiss on both cheeksDesigned by House of Dré, this Lonsdale Road addition dishes up an enticing fusion of Greek and Spanish cooking

By Sofia de la Cruz

-

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’

Creased, crumpled: S/S 2025 menswear is about clothes that have ‘lived a life’The S/S 2025 menswear collections see designers embrace the creased and the crumpled, conjuring a mood of laidback languor that ran through the season – captured here by photographer Steve Harnacke and stylist Nicola Neri for Wallpaper*

By Jack Moss

-

Artist Qualeasha Wood explores the digital glitch to weave stories of the Black female experience

Artist Qualeasha Wood explores the digital glitch to weave stories of the Black female experienceIn ‘Malware’, her new London exhibition at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, the American artist’s tapestries, tuftings and videos delve into the world of internet malfunction

By Hannah Silver

-

Ed Atkins confronts death at Tate Britain

Ed Atkins confronts death at Tate BritainIn his new London exhibition, the artist prods at the limits of existence through digital and physical works, including a film starring Toby Jones

By Emily Steer

-

Tom Wesselmann’s 'Up Close' and the anatomy of desire

Tom Wesselmann’s 'Up Close' and the anatomy of desireIn a new exhibition currently on show at Almine Rech in London, Tom Wesselmann challenges the limits of figurative painting

By Sam Moore

-

A major Frida Kahlo exhibition is coming to the Tate Modern next year

A major Frida Kahlo exhibition is coming to the Tate Modern next yearTate’s 2026 programme includes 'Frida: The Making of an Icon', which will trace the professional and personal life of countercultural figurehead Frida Kahlo

By Anna Solomon

-

A portrait of the artist: Sotheby’s puts Grayson Perry in the spotlight

A portrait of the artist: Sotheby’s puts Grayson Perry in the spotlightFor more than a decade, photographer Richard Ansett has made Grayson Perry his muse. Now Sotheby’s is staging a selling exhibition of their work

By Hannah Silver

-

Celia Paul's colony of ghostly apparitions haunts Victoria Miro

Celia Paul's colony of ghostly apparitions haunts Victoria MiroEerie and elegiac new London exhibition ‘Celia Paul: Colony of Ghosts’ is on show at Victoria Miro until 17 April

By Hannah Hutchings-Georgiou

-

Teresa Pągowska's dreamy interpretations of the female form are in London for the first time

Teresa Pągowska's dreamy interpretations of the female form are in London for the first time‘Shadow Self’ in Thaddaeus Ropac’s 18th-century townhouse gallery in London, presents the first UK solo exhibition of Pągowska’s work

By Sofia Hallström

-

Sylvie Fleury's work in dialogue with Matisse makes for a provocative exploration of the female form

Sylvie Fleury's work in dialogue with Matisse makes for a provocative exploration of the female form'Drawing on Matisse, An Exhibition by Sylvie Fleury’ is on show until 2 May at Luxembourg + Co

By Hannah Silver