Helmut Lang showcases his provocative sculptures in a modernist Los Angeles home

‘Helmut Lang: What remains behind’ sees the artist and former fashion designer open a new show of works at MAK Center for Art and Architecture at the Schindler House

Helmut Lang, artist and former fashion designer, has opened a new show of works at MAK Center for Art and Architecture at the Schindler House, the Los Angeles home designed by modernist architect Rudolph Schindler in 1921-22 and run as a satellite of the MAK – Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna.

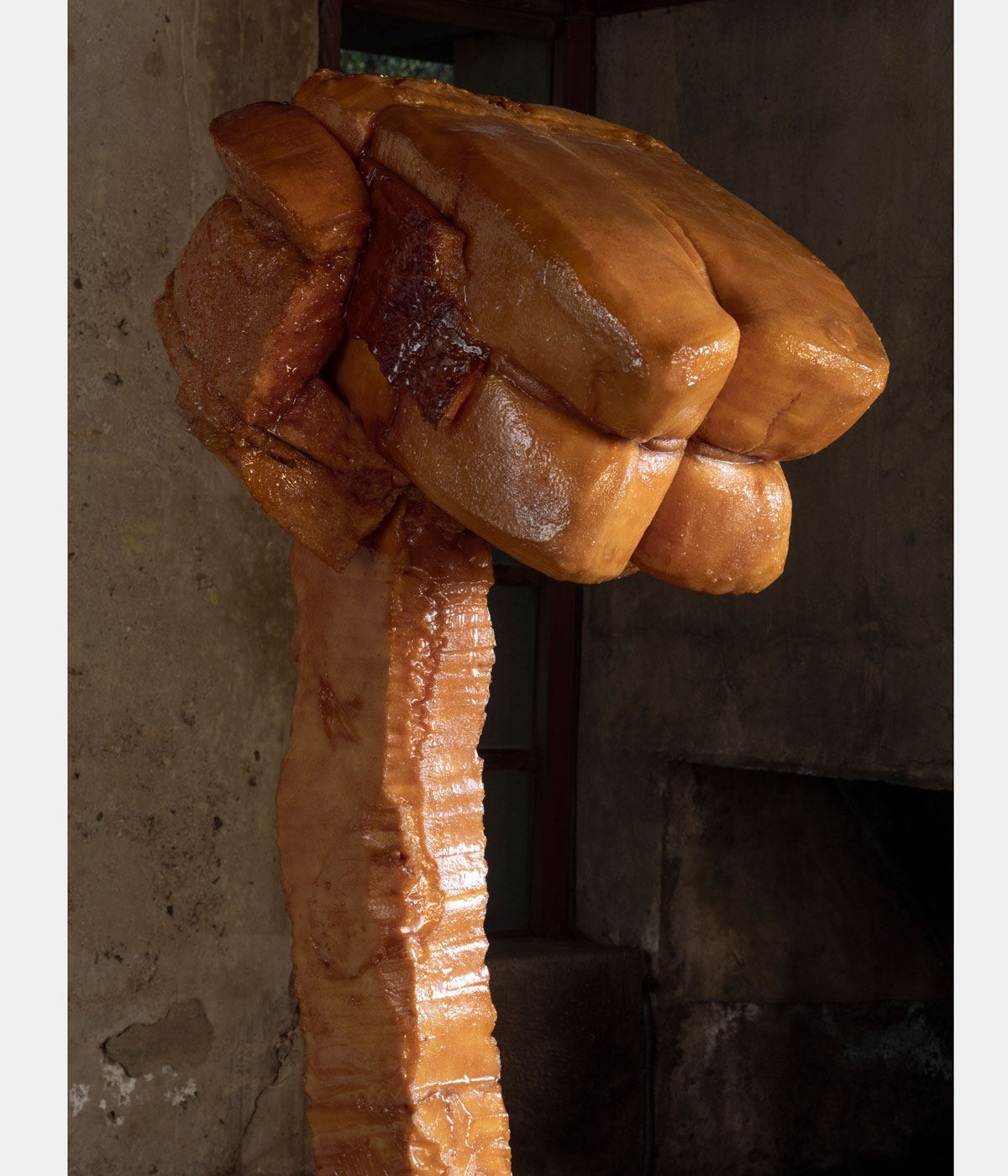

‘What remains behind’ comprises a series of sculptural works situated among the rooms of the minimalist house. The works harness unexpected materials of mattress foam, wax, resin, shellac and latex; the foam, drenched in the other materials, is contorted and bound into forms resembling closed fists as well as other bodily elements.

There is a visceral quality to the sculptures, recalling sticky cake or wet sponge, while their shapes oscillate between the sensual and the deformed, toying with desire and disgust. Titles such as ‘Fist I’ (2015–17) and ‘Prolapse II’ (2024) reflect this, while making clear the sexual narratives at play. The sculptures are accompanied by two small wall pieces, in which the materiality of shellac, plastic and wax is centred, exalted and framed.

The works were not created for the Schindler House, but the curation from Neville Wakefield – known for his site-specific approaches, including as artistic director of Desert X, and a longtime collaborator of Lang’s – powerfully connects the sculptures to the setting.

Arranged across five rooms, the works and their amber-brown hues reflect the home’s redwood frame, wooden panelling and striking copper fireplaces. ‘The scale, coloration and textures of the sculptures play off the physicality and histories of the house, which itself has always felt to me to be rather sculptural and bears the traces of its making, as well as its inhabitants,’ says Beth Stryker, director of the MAK Center.

The domesticity of the old mattress foam and its contortion begins to symbolise the way Rudolph Schindler radically rethought the nature of the home with this West Hollywood house. He designed the propositional, communal structure to be shared by two families – himself and his wife, and their friends Clyde and Marian Chace – with rooms flowing into one another and the outdoors, and often detached from set functions.

The house is a ‘storied repository of the many social, sexual and intellectual experiments that connected the new architectural forms to the lifestyles of those who built and inhabited them,’ Wakefield tells Wallpaper*. ‘Just as many of the physical barriers between inside and outside were broken down, so too were the psychological barriers that separate our internal and external conditions. It’s an idea that is echoed in the sculptures.’

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

The Austrian architect’s house eludes a fixed rooting in time, blending radical modernism with ancient Japanese design; traditional wood with innovative concrete. The sculptures of Lang, another Austrian creative, equally appear timeless: somehow both contemporary and prehistoric. Both artworks and architecture ’exist in a liminal space that is a threshold between past and present,’ says Wakefield.

This slippery grasp on time, where past and present coalesce, reflects Lang’s preoccupation with the notion of memory that the show’s title hints at; particularly the use of materials that feel imbued with past narratives. ‘Before it was sculpture, the mattress foam supported human bodies,’ says Wakefield. ‘Infused with this intangible memory, the reformed material speaks to the tension between the weight of the past and the promise of renewal.’

Ideas of memory, absence and presence – particularly in the domestic context – have also taken on new poignancy in the context of Los Angeles, in light of the devastating wildfires that ravaged the city this January. Materials indeed hold the stories of the past – but only if time allows them to survive.

‘Helmut Lang: What remains behind’ is on show at MAK Center for Art and Architecture at the Schindler House, Los Angeles until 4 May 2025

Francesca Perry is a London-based writer and editor covering design and culture. She has written for the Financial Times, CNN, The New York Times and Wired. She is the former editor of ICON magazine and a former editor at The Guardian.

-

RIBA Stirling Prize 2025 winner is ‘a radical reimagining of later living’

RIBA Stirling Prize 2025 winner is ‘a radical reimagining of later living’Appleby Blue Almshouse wins the RIBA Stirling Prize 2025, crowning the social housing complex for over-65s by Witherford Watson Mann Architects, the best building of the year

-

A24 just opened a restaurant in New York, and no one knows it exists

A24 just opened a restaurant in New York, and no one knows it existsHidden in the West Village, Wild Cherry pairs a moody, arthouse sensibility with a supper-style menu devised by the team behind Frenchette

-

Yinka Ilori’s new foundation is dedicated to play and joy: ‘Play gave me freedom to dream’

Yinka Ilori’s new foundation is dedicated to play and joy: ‘Play gave me freedom to dream’Today, artist and designer Yinka Ilori announced the launch of a non-profit organisation that debuts with a playscape in Nigeria

-

The Hammer Museum in Los Angeles launches the seventh iteration of its highly anticipated artist biennial

The Hammer Museum in Los Angeles launches the seventh iteration of its highly anticipated artist biennialOne of the gallery's flagship exhibitions, Made in LA showcases the breadth and depth of the city's contemporary art scene

-

Out of office: the Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: the Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekAnother week, another flurry of events, opening and excursions showcasing the best of culture and entertainment at home and abroad. Catch our editors at Scandi festivals, iconic jazz clubs, and running the length of Manhattan…

-

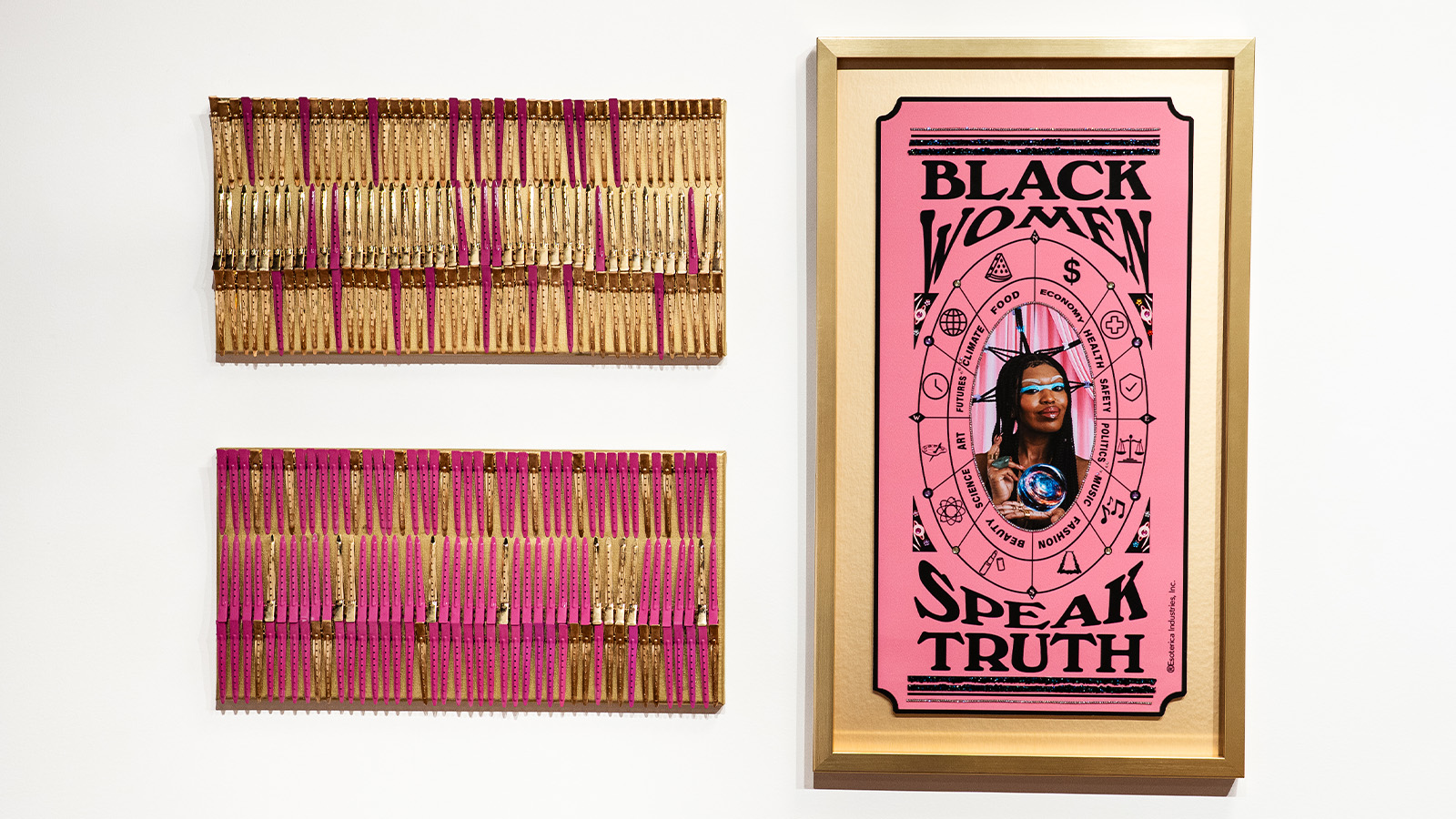

The spread of Butter: the Black-owned art fair where artists see all the profits

The spread of Butter: the Black-owned art fair where artists see all the profitsThe Indianapolis-based art fair is known for bringing Black art to the forefront. As it ventures out of state to make its Los Angeles debut, we speak with founders Mali and Alan Bacon to find out more

-

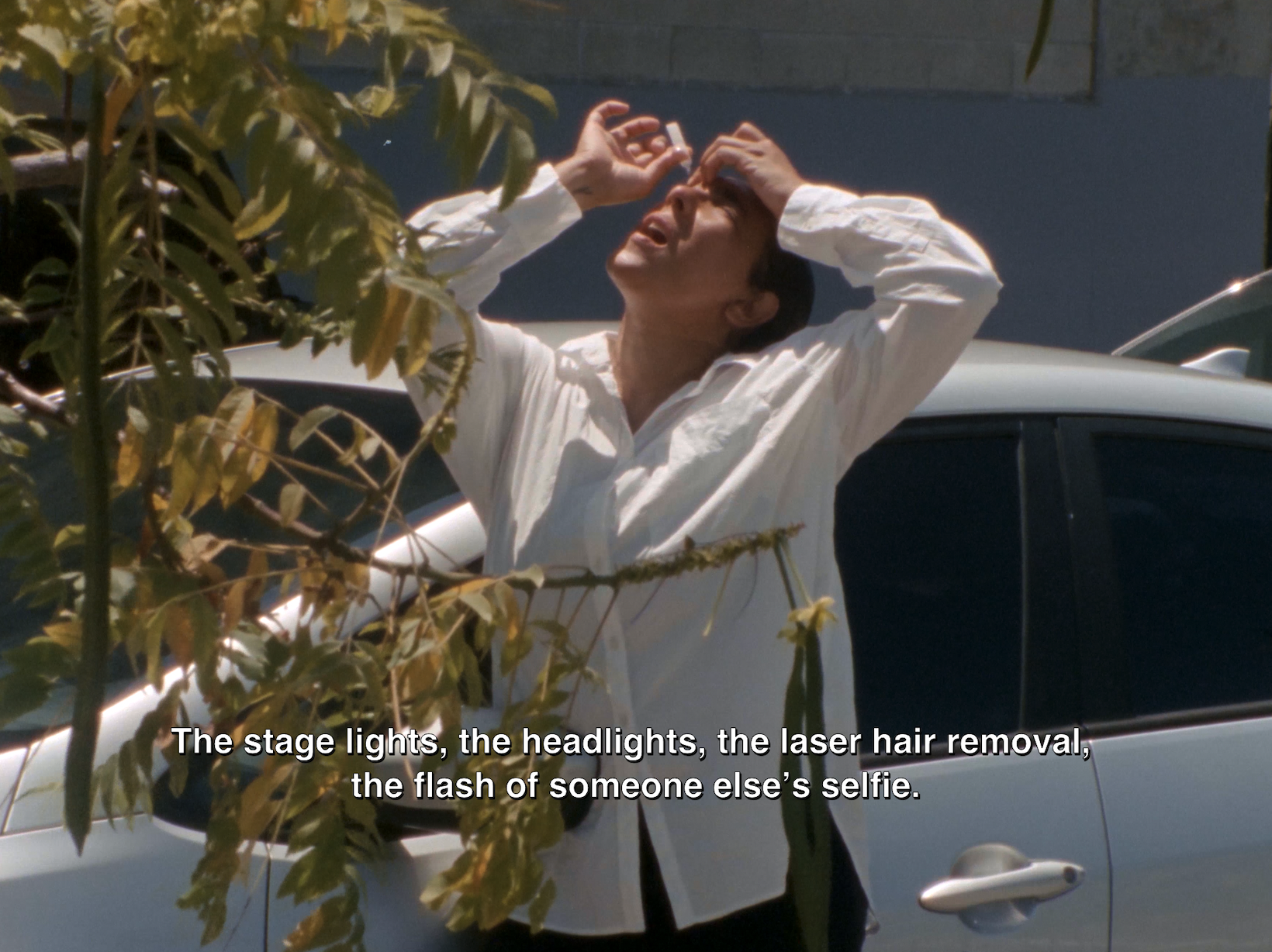

Unlike the gloriously grotesque imagery in his films, Yorgos Lanthimos’ photographs are quietly beautiful

Unlike the gloriously grotesque imagery in his films, Yorgos Lanthimos’ photographs are quietly beautifulAn exhibition at Webber Gallery in Los Angeles presents Yorgos Lanthimos’ photography

-

Cowboys and Queens: Jane Hilton's celebration of culture on the fringes

Cowboys and Queens: Jane Hilton's celebration of culture on the fringesPhotographer Jane Hilton captures cowboy and drag queen culture for a new exhibition and book

-

New gallery Rajiv Menon Contemporary brings contemporary South Asian and diasporic art to Los Angeles

New gallery Rajiv Menon Contemporary brings contemporary South Asian and diasporic art to Los Angeles'Exhibitionism', the inaugural showcase at Rajiv Menon Contemporary gallery in Hollywood, examines the boundaries of intimacy

-

Don't miss these seven artists at Frieze Los Angeles

Don't miss these seven artists at Frieze Los AngelesFrieze LA returns for its sixth edition, running 20-23 February, showcasing over 100 galleries from more than 20 countries, as well as local staples featuring the city’s leading creatives

-

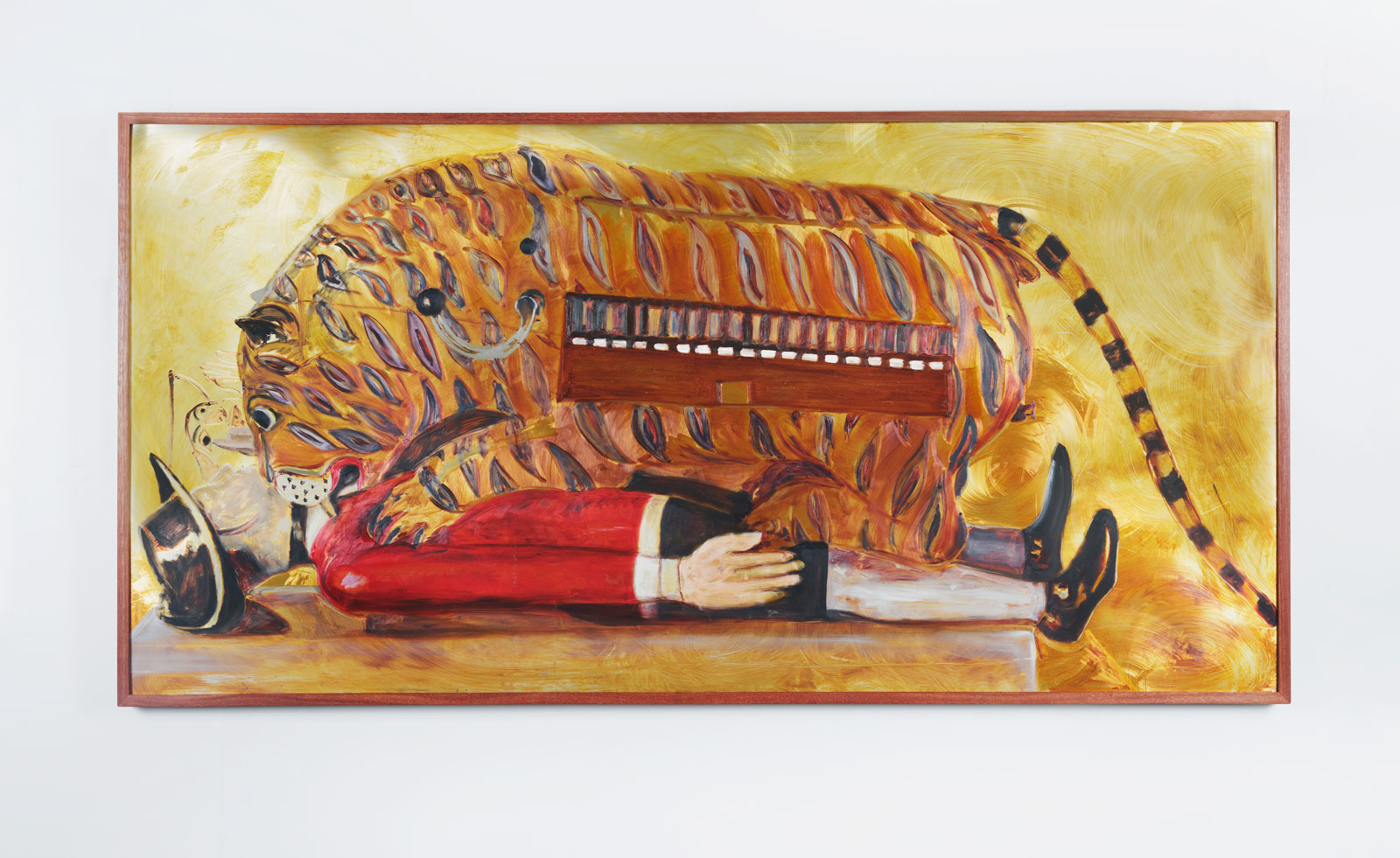

Pop culture, nostalgia and familiarity: Sam McKinniss in LA

Pop culture, nostalgia and familiarity: Sam McKinniss in LAArtist Sam McKinniss’ solo exhibition of paintings at David Kordansky Gallery in Los Angeles taps into familiarity, loss, and nostalgia