Inside Noah Davis' rich, cinematic world

Nearly a decade after Noah Davis' passing, a touring retrospective sets out to bring his work to a wider audience

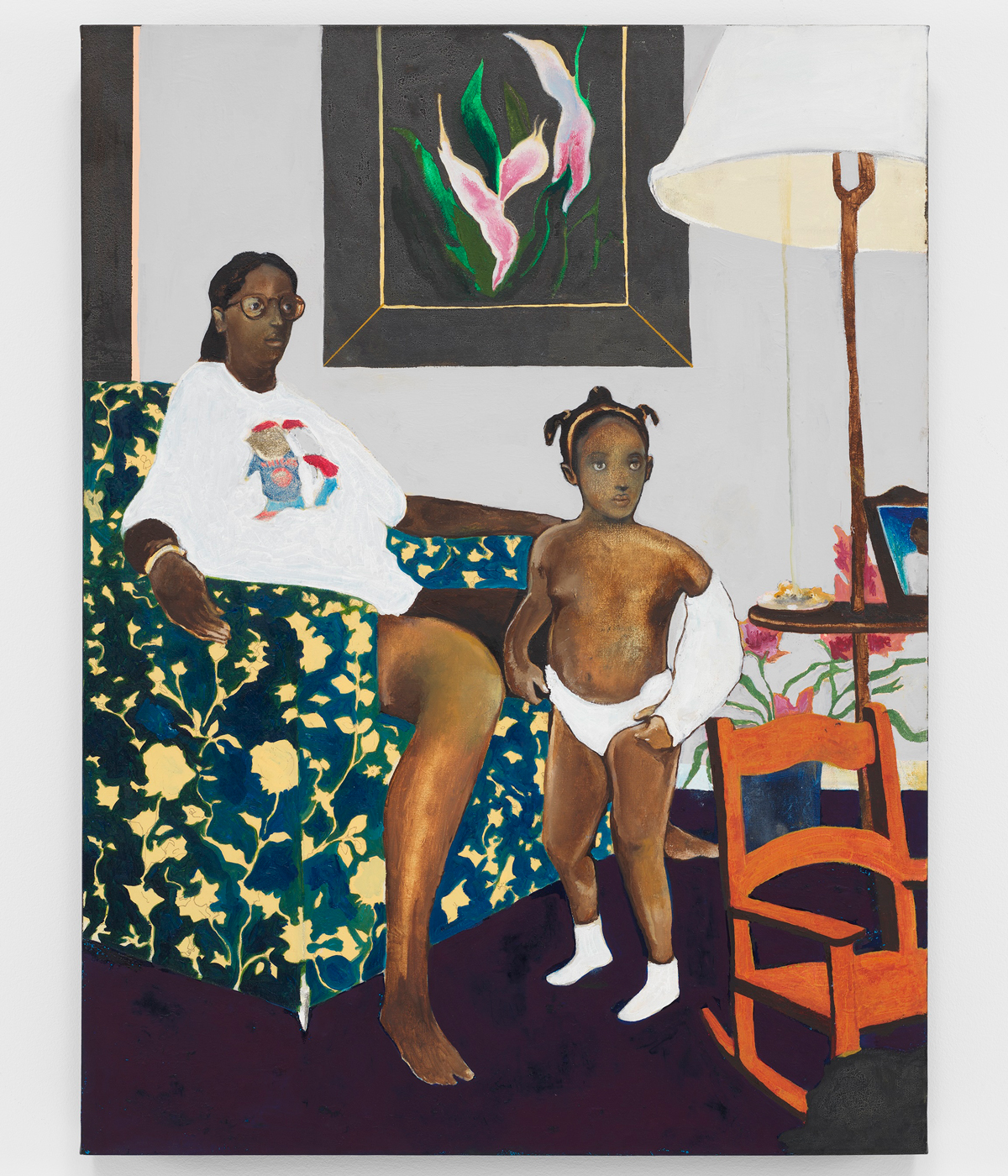

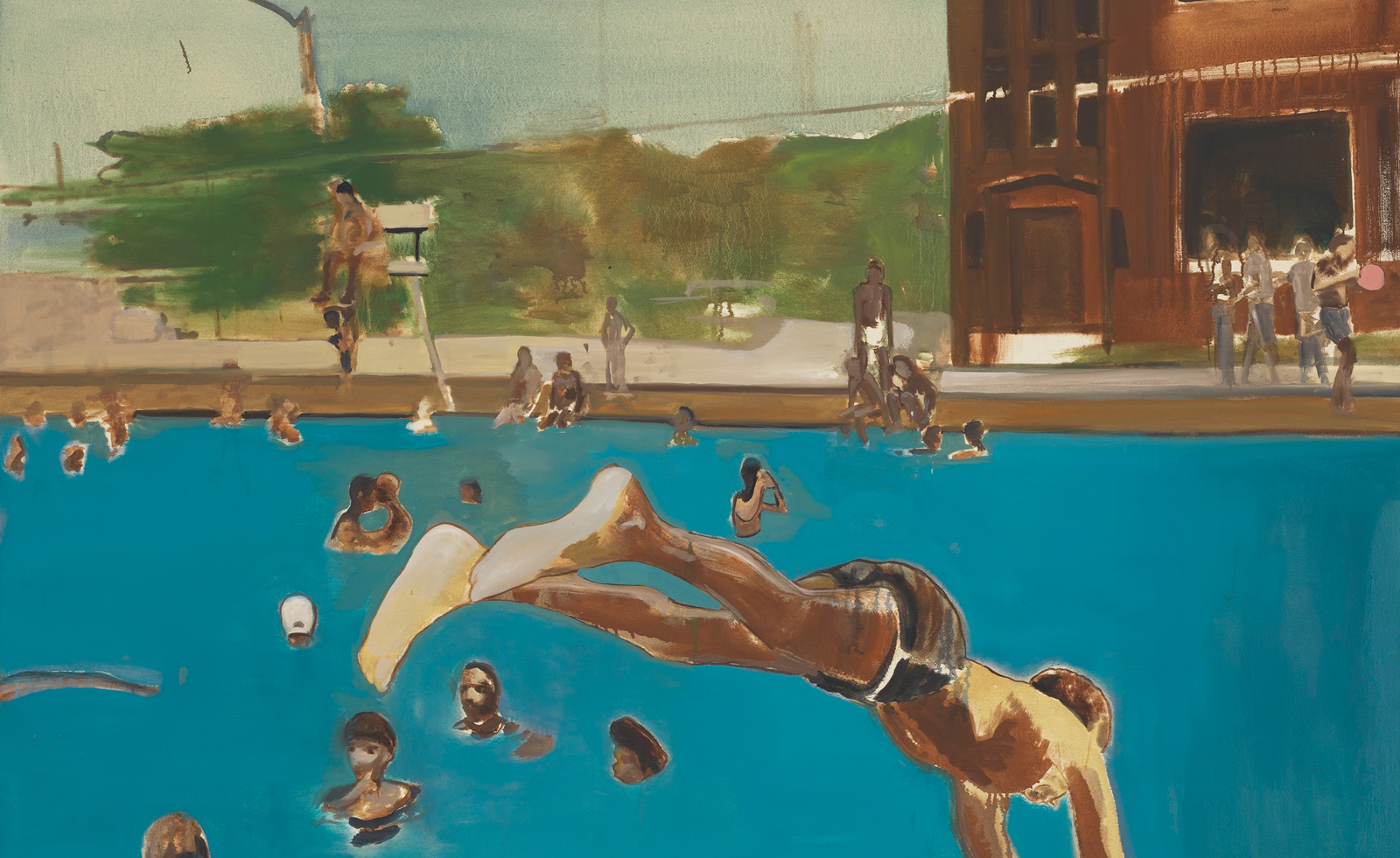

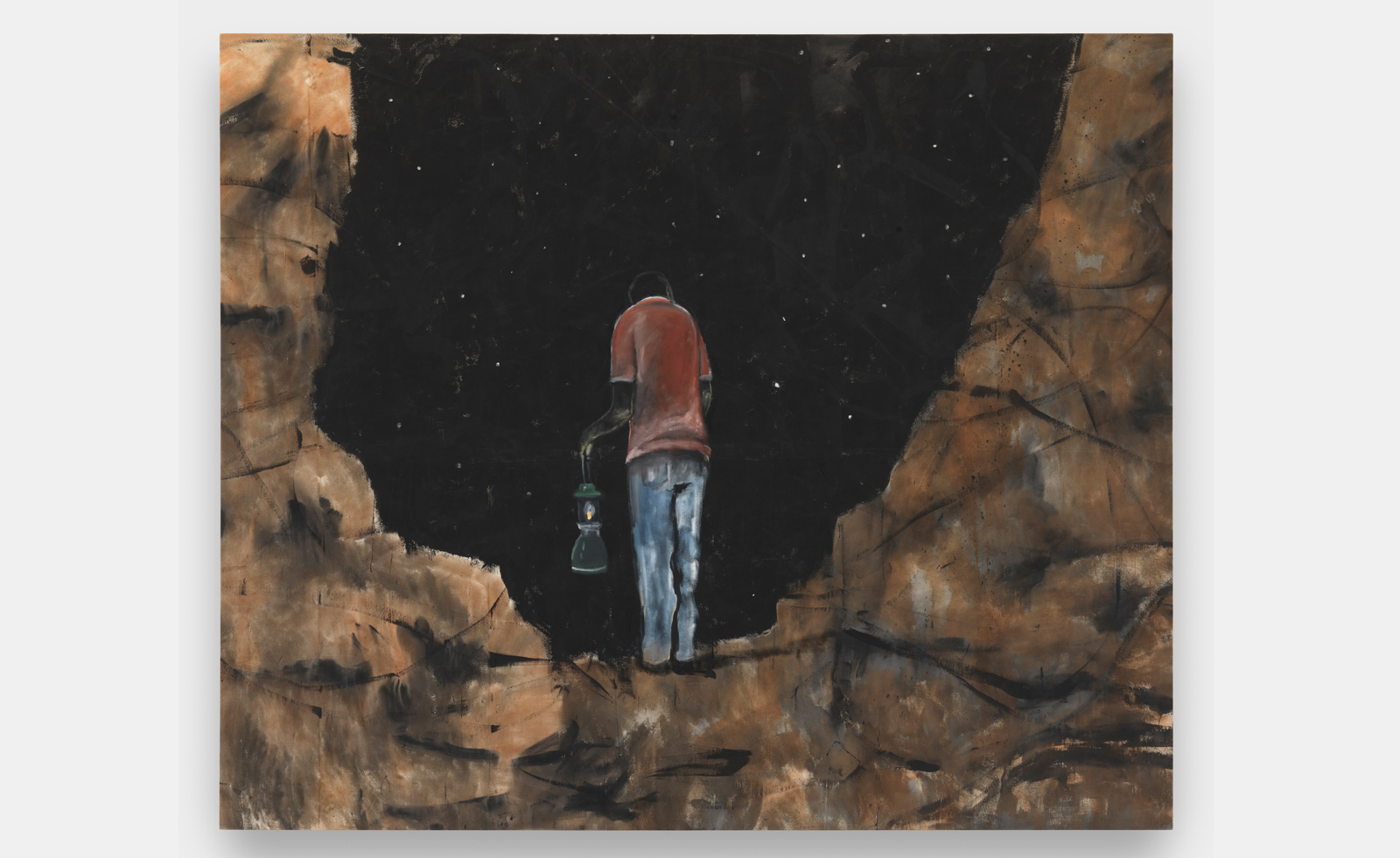

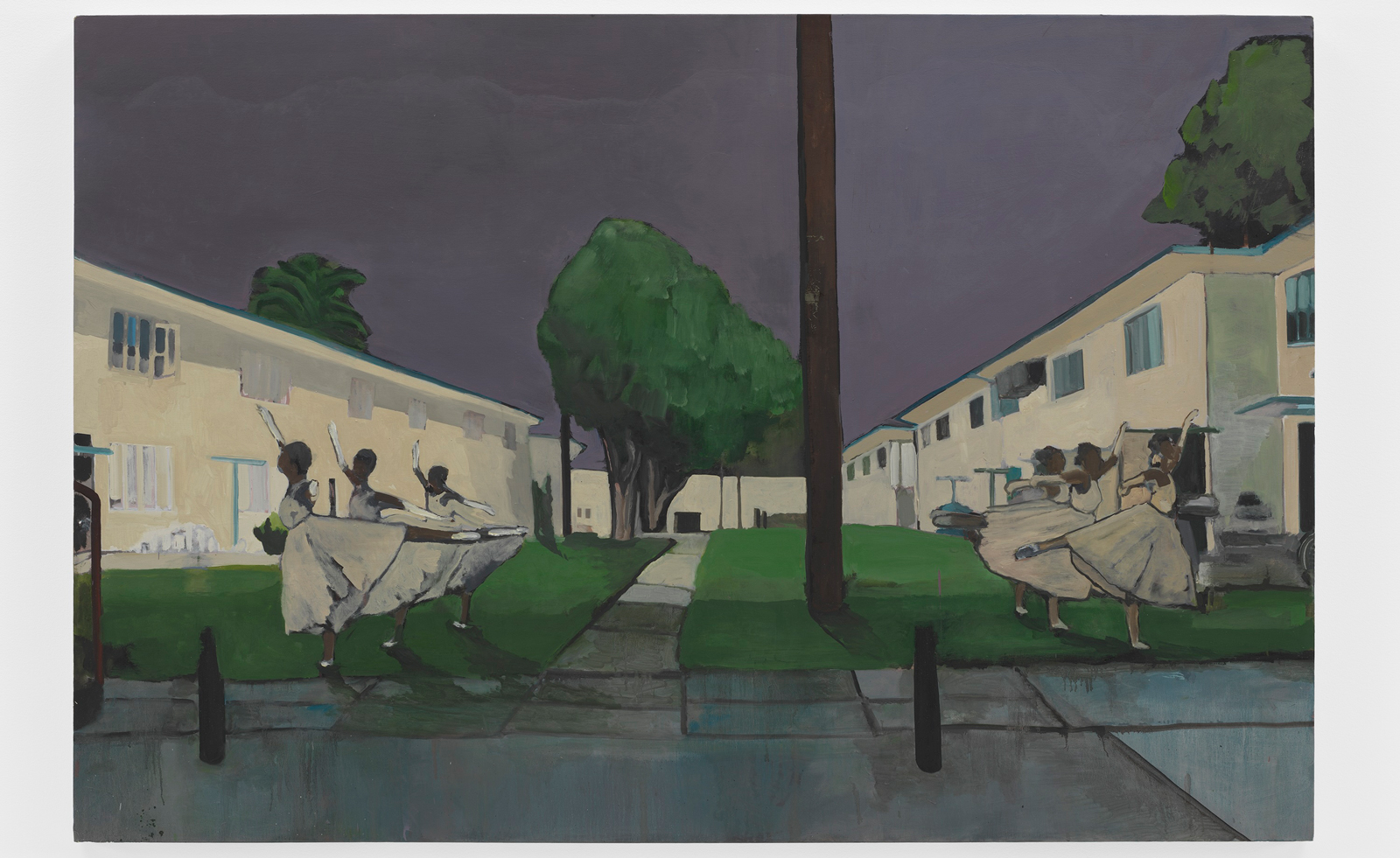

The figures in Noah Davis’s paintings, portrayed within modernist architecture, in domestic interiors, or in public places of leisure, are invariably black. They are ordinary men, women, and children intimately captured mid-repose, at play, or going about their daily lives. In some works, they’re projected into extraordinary scenarios that are futuristic, cinematic, unsettling and enigmatic. Davis’s representation of black life is at the core of his painterly interrogation of the fiction of difference. Or, in the artist’s own words, “Race plays a role in as far as my figures are black. The paintings aren’t political at all though. If I’m making any statement, it’s to just show black people in normal scenarios, where drugs and guns are nothing to do with it.”

First capturing the art world’s attention in 2007, Davis, up until his untimely death, in 2015, from a rare cancer at the age of 32, has authored a rich and magnetising vernacular whose idiosyncrasy is yet to be fully acknowledged. Davis’s ability to switch between canonized painting styles and make them his own while referencing wide-ranging influences from Rothko to Bacon, Kerry James Marshal, Marlene Dumas, Peter Doig and Luc Tuymans, or from Leipziger Schule to Magical Realism, enhances the psychologically demanding aura of his work. Now, nearly a decade after his passing, a touring retrospective sets out to bring Davis’s work to a wider audience.

Noah Davis, Single Mother with Father Out of the Picture, 2007–2008. Private Collection

Making its first stop at Das Minsk — a private museum in Potsdam, near Berlin — the retrospective will travel to the Barbican in February of 2025, and to the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles, where Davis was an influential member of the local art community. He and his wife, Karon Davis, founded The Underground Museum in the historically Black and Latinx neighbourhood of Arlington Heights. It was a singular venue, active from 2012 until 2022, that brought art by the likes of William Kentridge and Deana Lawson to new audiences. Spanning the short eight years of his career, the retrospective features works on paper, sculptures, and dozens of paintings, several of which might be familiar to viewers from the 2022 Venice Biennale.

Arranged chronologically, and starting on the upper-level, the show at Das Minsk opens with the work 40 Acres and a Unicorn (2007), showing a black figure on a white unicorn emerging from a dark, void background. The title references the “forty acres and a mule” that were promised to freed enslaved families at the end of the American Civil War. But quickly, the phrase became shorthand for the failure of the post-war Reconstruction era. The painting’s mythical animal replaces the simple mule to evoke “a future perpetually deferred”, curator Helen Molesworth, a friend and key supporter of Davis’s work, writes in the show’s catalogue. On the theme of perpetual promise, it also implies the biblical concept of a Messiah who is believed to appear at the End of Days on a white donkey — or perhaps it recalls the one that Jesus rode to Jerusalem according to the New Testament.

Noah Davis, 1975

Isis (2009) portrays Davis’s wife Karon as the Egyptian goddess of magic in a golden, fan-winged costume. It holds, frozen in time, a memory of creative play in the couple’s back yard; at the same time, the motif harks back to the iconic works of trailblazing women artists, such as the recently deceased Rebecca Horn, who constructed and performed extensions to her body with fans, sails, and feathers; or the pioneering American dancer Loie Fuller, who experimented with movement, lighting and the stage through similar add-ons. In the ground-floor gallery, the striking nine-part series 1975 (2013) lovingly depicts urban life in a black neighbourhood. It is based on photos that the artist’s mother had taken as a high-schooler but never developed. Years later, Davis reinterpreted the every-day scenes caught on film in a faded palette that appears unnatural, unnerving, and places the scenes already timestamped by markers such as fashion, automobiles, and hairstyles in the mid-seventies of the mind.

That the touring retrospective opens at Das Minsk, a small institution owned by German tech billionaire and collector Hasso Plattner, speaks to its outgoing director Paola Malavassi’s ability to enmesh the locality on the outskirts of Berlin within a larger international conversation. It is also thanks to her uncompromising curatorial clarity that this leg of the exhibition includes several important works that will not be exhibited in London or L.A.

One of these is tilted Leni Riefenstahl (2010). Based on a photo from Riefenstahl’s 1976 Africa photobook, Davis’s painting appropriates a charged image, claiming its loaded if iconic iniquity through the gaze of a black American painter.

Noah Davis, Painting for My Dad, 2011. Rubell Museum

In her shot, the Nazi propagandist walks alongside a member of a traditional community living in the Nuba mountains of Sudan. Her colonial style of dress is meant to cast Riefenstahl as an ethnographer, an aging photographer-researcher, while the African man’s towering, gleaming body is fully exposed. His is a lean and powerful stature; the photographer’s fixation on perfect bodies is entirely Olympia. They’re holding hands, and the man is carrying the photographer’s bag as they descend down a mountain path. In Davis’s painting, the background melts into abstracted, round-edged boulders, and Riefenstahl’s shadow is but a black, formless mass. What Davis couldn’t have known when he titled his painting is that the photographer’s companion will not remain nameless for much longer. The Ethnological Museum Berlin and the Art Library, Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation have begun a joint project of researching and cataloguing Riefenstahl’s Nuba photographs and films together with representatives of Nuba societies. They have recently managed to identify and contact the man in the photograph. The story of the image, and it reinterpretation by Davis, is entangled in the genocidal violence and tumult of Germany’s dark history — and is still unfolding.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

The exhibition Noah Davis is initiated by Barbican, London and DAS MINSK, Potsdam. This project is organized in close collaboration with the Estate of Noah Davis and David Zwirner Gallery.

DAS MINSK, Potsdam 7 September 2024 – 5 January 2025.

Barbican, London 6 February – 11 May 2025.

Hammer Museum, Los Angeles: 8 June – 31 August 2025

Noah Davis, Pueblo del Rio: Arabesque, 2014. Miguel Pimentel

-

Extreme Cashmere reimagines retail with its new Amsterdam store: ‘You want to take your shoes off and stay’

Extreme Cashmere reimagines retail with its new Amsterdam store: ‘You want to take your shoes off and stay’Wallpaper* takes a tour of Extreme Cashmere’s new Amsterdam store, a space which reflects the label’s famed hospitality and unconventional approach to knitwear

By Jack Moss

-

Titanium watches are strong, light and enduring: here are some of the best

Titanium watches are strong, light and enduring: here are some of the bestBrands including Bremont, Christopher Ward and Grand Seiko are exploring the possibilities of titanium watches

By Chris Hall

-

Warp Records announces its first event in over a decade at the Barbican

Warp Records announces its first event in over a decade at the Barbican‘A Warp Happening,' landing 14 June, is guaranteed to be an epic day out

By Tianna Williams