Art futurists go in search of micro-utopias in Nairobi

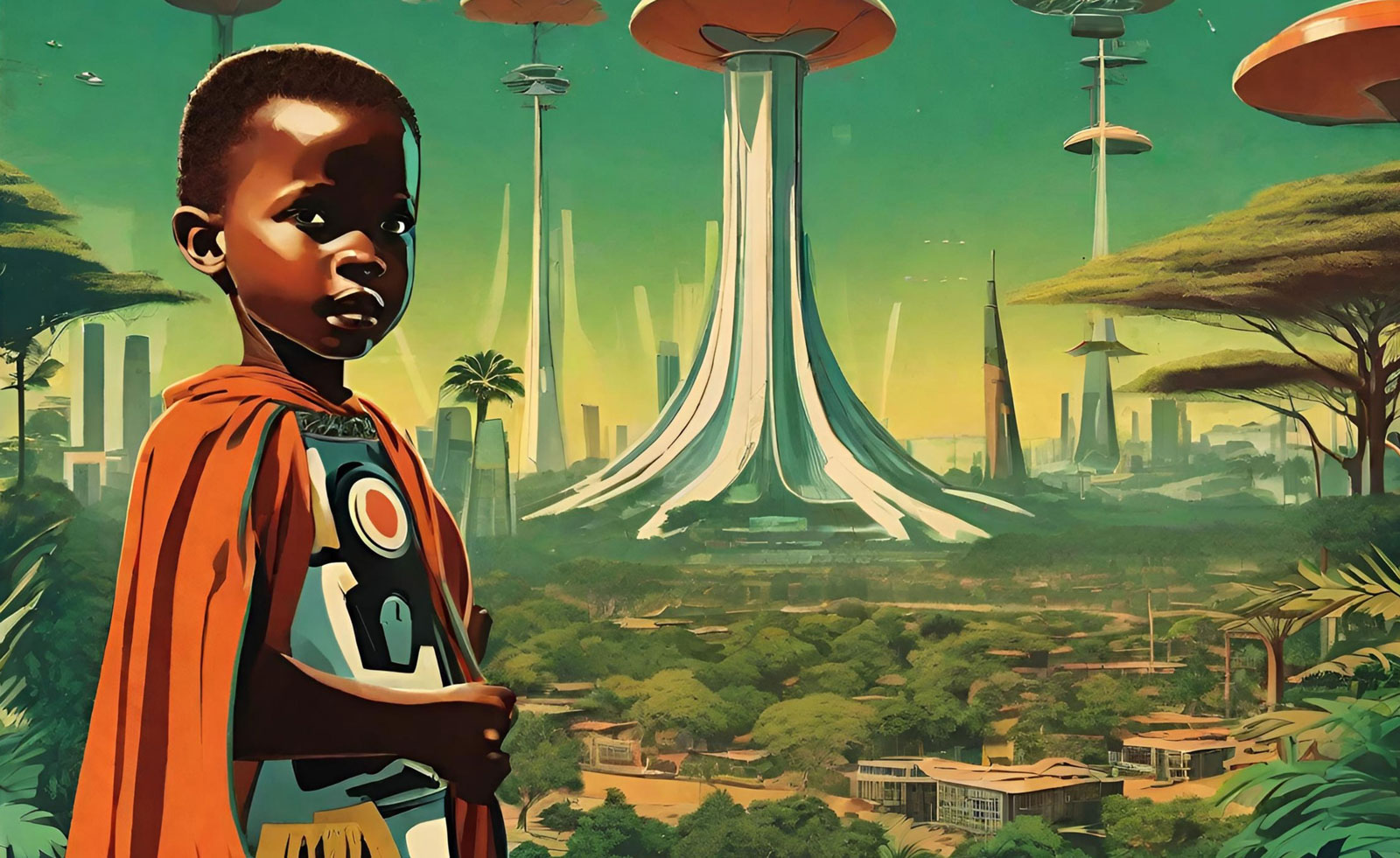

‘Hakuna Utopia? In Search of Micro-Utopias’ sees Nairobi-based art collective Kairos Futura harness visions of the future to provoke change; artist Ajax Axe tells us more

For its most extensive exhibition yet, Nairobi-based art futurist collective Kairos Futura explores issues residents of Kenya's capital face and possibilities of a better life. ‘Hakuna Utopia? In Search of Micro-Utopias’ features painting, drawing, printmaking, sculpture, and site-specific installations across satellite locations that speak to themes of utopia, apocalypse, and resilience. The show opened in July at Kairos Atelier, the collective’s warehouse studio and gallery in Nairobi's industrial area.

Kairos Futura empowers artists, designers, and scientists to use the power of imagination to engage their communities. The group comprises Ajax Axe, Stoneface Bombaa, Coltrane McDowell, Neemo Mungai, Lincoln Mwangi, Shabu Mwangi, and Abdul Rop.

Here, Ajax Axe tells Wallpaper* more about the exhibition, and how arts can lead to social change.

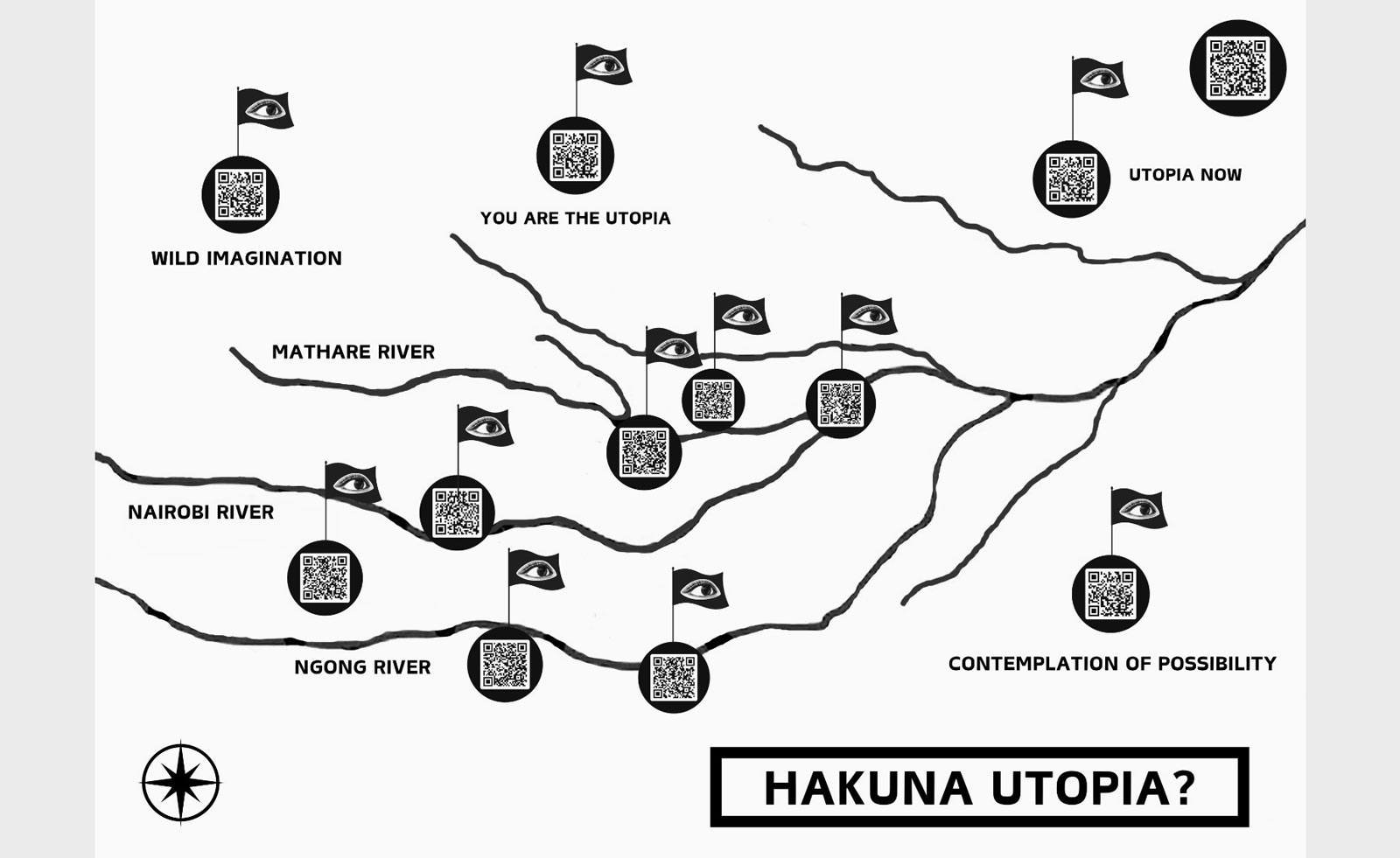

Kairos Futura, ‘Hakuna Utopia? In Search of Micro-Utopias’ in Nairobi

Map of Hakuna Utopia

Wallpaper*: What’s the story behind the title of the exhibition?

Ajax Axe: ‘Hakuna Utopia’ is a phrase Abdul Rop, Lincoln Mwangi, and I began using while working on an exhibition on Lamu Island in Northern Kenya in 2021. It translates to ‘There is no utopia’ in Swahili. Lamu is often labelled a utopia, with beautiful architecture, beaches, and no cars. Yet behind [its] beautiful façades, there were hidden ugly things – violence, greed, poverty, and ecological destruction. While there, we became interested in the visuals and language of utopia and apocalypse, and how landscapes with these labels could often exist side by side.

When we started working in Nairobi in 2022, the dichotomy between different neighbourhoods evoked similar questions about money, power, and access to beauty and nature. Is there no utopia? Is utopia something we overlook? Can we find it in unexpected places? We asked ourselves these questions when we started developing this body of work.

W*: Can you speak about the show’s themes of utopia, apocalypse, and resilience to challenges?

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

AA: Nairobi is a city of extreme contrasts. Some areas are lush and almost jungle-like, while in other parts of the city, there are virtually no trees or green spaces left. In the more expensive neighbourhoods, you can eat sushi or a tomahawk steak, while a massive percentage of people are surviving on bread and milk because they can’t afford anything else.

In a way, utopia and apocalypse exist simultaneously for many people, even though it can be uncomfortable to acknowledge them; we felt these themes demanded critical integration into the economics of pleasure and suffering. As we explored the topic, we began to think of utopia and apocalypse as a social and personal construct. Who can prove me wrong if I declare a place to be a utopia? Who can define the truth besides myself if I decide an apocalypse is happening? Our stories about reality become true because we believe in them. So, for this exhibition, we wanted to explore these abstract fantasies on both the personal level and the collective experience of utopia and apocalypse.

Lincoln Mwangi’s tryptic, An Introspection and Retrospection of Facilities, is about how utopia or dystopia is constructed in the mind from visual stimuli we experience daily. In Kenya, one symbol of personal hell for many people is school chairs, because of the punitive, colonial education system that still exists here. I wanted to transform these chairs into something that equated to joy, hope, utopia, or whatever you want to call it, so I made several school chairs into ‘micro-utopias’. All of the work for this exhibition and its satellite locations is intended to provoke deeper dialogue about what kind of story we’re creating together and whether we can change that story if we deconstruct it consciously.

Utopia Chair #1, Ajax Axe, 2024. Mixed media sculpture. Axe transformed school chairs, a symbol of systemic suffering for young people in Kenya, into playful installations meant to inspire pleasure and curiosity

W*: What’s the importance of speaking about the issues addressed in this exhibition?

AA: As an arts futurist collective, we believe that new visions for the future are our generation's most significant opportunity and challenge and, thus, the most important topic we can address in our art. When we think about a better future, ignoring the injustices we witness in our communities now is impossible. Social and ecological injustices are how people experience personal and community apocalypse daily. And yet, there is still so much hope, resilience, and power amid such intergenerational trauma.

The central theme of this show is that looking for moments of utopia can be an act of resistance and a way to reframe existing narratives about communities. One site-specific piece that Stoneface Bombaa and I created is The Jungle Room, an indoor installation in an informal settlement called Mathare. It’s a space we’ve transformed into a sanctuary for the community to experience peace and nature. Finding quiet, safe spaces in Mathare, a neighbourhood of nearly half a million people, is often challenging. We rented a corrugated metal church and have built a vertical garden from repurposed charcoal stoves. Stoneface, from Mathare, wrote, ‘utopia is when we make something terrible beautiful’.

Another artist, Abdul Rop, wanted to explore social justice in his Utopia Kangas. Kanga is a traditional textile design that combines patterns, symbols, and text to create visual metaphors for social issues. Rop wanted to reimagine the Kanga with messaging around ‘the relationship between the fulfillment of our three basic needs – food, shelter, and water – and the vision of a utopian society’. In these works, he invites viewers to ‘imagine a world where everyone has the opportunity to thrive, free from suffering and inequality’.

W*: What can you share about the ‘Micro-Utopias’ highlighted in the exhibition?

AA: With micro-utopias, we wanted to draw attention to places and organisations doing exceptional work in difficult circumstances and with very limited funds.

For example, Shabu Mwangi, one of the artists exhibiting in ‘Hakuna Utopia’, has created an art space called Wajukuu Arts Centre in Mukuru, the informal settlement he’s from. He and his friends teach hundreds of young people, have a garden, and, most importantly, a place to feel safe and explore their creative abilities. Because of its location, Wajukuu doesn’t get many visitors, but it’s such an inspiring place, and we want to encourage people to visit it.

The Jungle Room is another place on the Utopia Map. It’s in the middle of Mathare, and most people from the more affluent parts of the city don’t go there. We hope the Jungle Room will be where art lovers and activists can connect and create new opportunities for young creative minds.

The Utopia Within, Lincoln Mwangi, 2024. Mixed Media on canvas. Mwangi explores the idea of the mind as an ocean of infinite utopias

W*: What role does art play in fostering social change?

AA: Art can transform topics that are painful and frightening. When we reframe or reimagine problems and inequalities through the lens of art, we create a space where people can see something from a fresh perspective or become willing to engage with an idea that feels threatening or untenable.

Another way art can bring about social change is by bridging the socio-economic barrier between communities. Art is often seen as a consumable for the wealthy yet creativity is our birthright and greatest strength. Art can be available to all of us and spiritually, we can connect and build horizontal communities through the transcendental power of art. That’s what we hope to do through our ‘Hakuna Utopia? In Search of Micro-Utopias’ exhibition and all of our projects.

W*: Is there anything else you'd like to add?

AA: It would be impossible to imagine Kenya’s future without mentioning the ongoing protests and mobilisation of Gen Z people here. Kenya is experiencing a moment of incredible uncertainty but also incredible possibility. We feel that the conversations we’re trying to evoke with [the exhibition] are critical in the current political environment and the situation here is emblematic of a wave of change burgeoning all over the world.

Our interconnectivity has sparked a great political awakening juxtaposed against the hideous end game of 70-plus years of the military industrial complex selling arms to anyone willing to pay. That duality will be the utopia and apocalypse that the coming generation faces, and how they shape the narrative for the future will likely decide the next 500 years of civilisation.

‘Hakuna Utopia? In Search of Micro-Utopias’ is on view at Kairos Atelier in Nairobi, Kenya, until 1 November 2024

-

Extreme Cashmere reimagines retail with its new Amsterdam store: ‘You want to take your shoes off and stay’

Extreme Cashmere reimagines retail with its new Amsterdam store: ‘You want to take your shoes off and stay’Wallpaper* takes a tour of Extreme Cashmere’s new Amsterdam store, a space which reflects the label’s famed hospitality and unconventional approach to knitwear

By Jack Moss

-

Titanium watches are strong, light and enduring: here are some of the best

Titanium watches are strong, light and enduring: here are some of the bestBrands including Bremont, Christopher Ward and Grand Seiko are exploring the possibilities of titanium watches

By Chris Hall

-

Warp Records announces its first event in over a decade at the Barbican

Warp Records announces its first event in over a decade at the Barbican‘A Warp Happening,' landing 14 June, is guaranteed to be an epic day out

By Tianna Williams