‘Leigh Bowery!’ at Tate Modern: 1980s alt-glamour, club culture and rebellion

The new Leigh Bowery exhibition in London is a dazzling, sequin-drenched look back at the 1980s, through the life of one of its brightest stars

‘Leigh Bowery!’ at Tate Modern is a groundbreaking show for a number of reasons. Through the lens of the legendary performance artist, muse and designer (1961-1994), we see the emergence and impact of a small but mighty subculture that left an impression on the UK cultural landscape, still in evidence today.

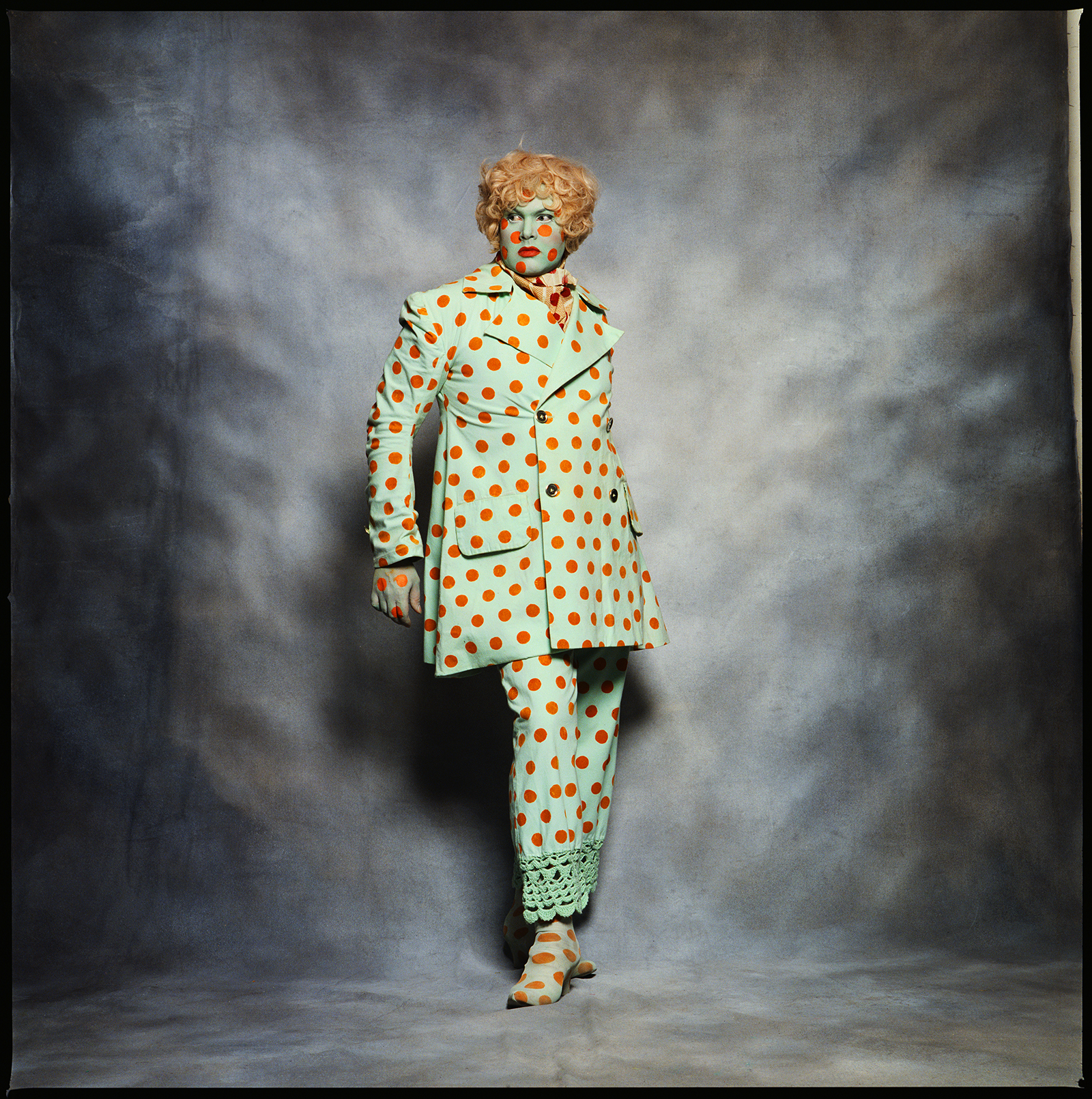

Fergus Greer, Leigh Bowery Session 7, Look 37 June 1994 ©Fergus Greer. Courtesy of the Michael Hoppen Gallery

The exhibition covers Bowery’s life once he arrived in the UK from Australia, in 1980. He had, while working in Burger King, seen an advertisement for Andrew Logan’s Alternative Miss World contest, a legendary queer beauty pageant and art extravaganza. It was here he found his tribe in the New Romantics and pushed this scene’s boundaries both within club culture in London (as celebrated in ‘Outlaws: Fashion Renegades of 80s London’ at the capital’s Fashion and Textile Museum) and as a public figure.

Fergus Greer, Leigh Bowery Session 3 Look 14. August 1990 ©Fergus Greer. Courtesy of the Michael Hoppen Gallery.

Tate Modern’s new exhibition (27 February – 31 August 2025) covers Bowery’s impact on both mainstream and subculture, looking at his personal life and work through the spaces in which he thrived – the home, the club, the studio and the street. Uniting he film and art created about and around him and his own work, the exhibition reveals the fun and the struggle of living an alternative life in the 1980s.

Fergus Greer, Leigh Bowery Session 4, Look 19, August 1991 ©Fergus Greer. Courtesy of the Michael Hoppen Gallery.

Curator Fiontán Moran worked on the exhibition with Bowery’s widow and artistic partner Nicole Rainbird, who holds Bowery’s estate, and the collaboration was a close one.

‘Fiontán came around to my house and looked through boxes and boxes of photographs and archival material… and all the costumes,’ says Rainbird. ‘He just sat there photographing everything and formulated his ideas.’

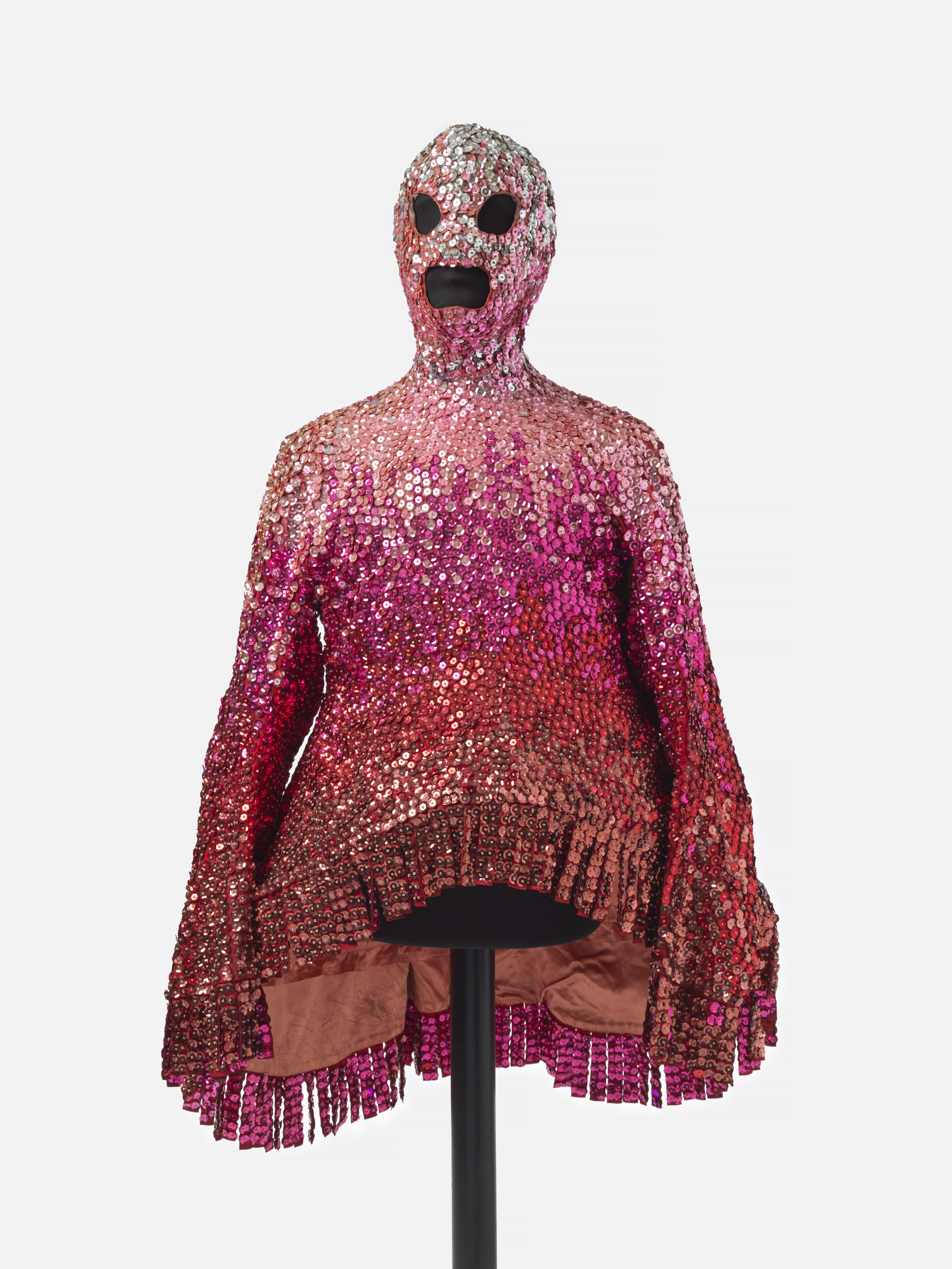

Displays are drenched in sequins and filled with glittered gimp masks, neck corsets, hilarious, sexy postcards, and personal items like a homemade stacked trainer. The exhibition is a true window into Bowery’s practice and his circle, which included choreographer Michael Clark, Boy George, Trojan, Princess Julia and Charles Atlas. Their party scene, which centred on Bowery’s own club night Taboo, and venues such as The Cha-Cha Club and the famous Blitz Club, was notorious for its alt-glamour, bitchy barbs and hedonism. It was all about the getting ready and having a striking and unique look of your own creation.

‘I thought it was important to look at someone that contributed a great deal to art and culture at the time, but also beyond, [to] make a show that I hope connects to people’s everyday experience of the city and being creative,’ said Moran.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

We see enlarged busts, contorting costumes, obscured faces and highlighted genitals – everything exaggerated and covered with patterns and spots that are thought by some to allude to the lesions associated with AIDS. There is a horror-glamour and aggressive rejection of norms in the work of Bowery and his friends that is palpably exciting.

The show starts with a focus on the home, Bowery’s flat and his early ideas. Charles Atlas’ fictional documentary on Michael Clark, Hail the New Puritan, 1986, specifically shows everyone getting ready to go out. This is seen alongside John Maybury’s film about Bowery, Read Only Memory, 1989, included to provide context of the times. This was Thatcher’s Britain, a time of inequity, government-level homophobia, and the AIDS crisis.

This helps explain the rebelliousness of this group of artists, who met when Clark saw Bowery in a club and asked him to create costumes for his performances. Clark was pushing the boundaries of acceptability in contemporary dance and Bowery’s costumes brought an edge to already controversial performances.

‘The Michael Clark ballets were really heavily criticised,’ Rainbird recalls. ‘And [people] did not like Leigh being part of the performance. It was because it wasn’t conventional. I suppose it was outside the box. And, you know, I think they just felt that ballet should be a particular way. I think they felt that what Leigh introduced was more pantomime.’

Rainbird also notes that people outside traditional dance would come to the performances in order to attend the after-parties, which were a thing of urban myth.

Today, of course, Clark is a revered presence on the cultural scene and applauded for combining disciplines and ideas. He is just one example of the famous figures who collaborated with Bowery, albeit one of the most prolific. Throughout the Tate Modern show, there is work from other artists, including Jeffery Hinton and Dick Jewel. There is also a deep exploration of the queer club scene of the 1980s, which is peppered with famous faces and nightlife legends, such as John Galliano, Jalle Bakke and Marc Vaultier. There are also photographs by an emerging Nick Knight and clips from TV classic The Clothes Show.

‘I think in terms of looking at contemporary art, the creative scene and landscape, that period continues to be an inspiration, especially when you think [Bowery] did a lot of these performances and made a lot of these garments for very meagre [gains],’ says Moran.

There are several works on show by Lucian Freud, who painted Bowery and his friend the writer Sue Tilley. Freud continued to paint Bowery up until his death, and this friendship helped push the latter towards the contemporary art world, creating acceptability outside club land and pop culture. Freud’s paintings are juxtaposed with the outré performances Bowery was making at the time, but also with the creeping of the commercial world into subculture.

Bowery’s first performance in a gallery setting – at the D’Offay Gallery, in 1988 – put him on a trajectory into the contemporary art world that we will never see completed, but Rainbird thinks he would have liked to make some proper money and would never have settled on a genre.

‘Leigh Bowery!’ tells the story of a time through the life of one of its brightest stars and his circle, but it also hints at the essence of a man who lived his life performing, whether this was on stage at Saddler’s Wells or just popping to the shops.

‘Leigh Bowery!’ is at Tate Modern, London, 27 February – 31 August 2025, tate.org.uk

Also catch ‘Outlaws: Fashion Renegades of 80s London’ at the Fashion and Textile Museum, London, until 9 March 2025

Amah-Rose Abrams is a British writer, editor and broadcaster covering arts and culture based in London. In her decade plus career she has covered and broken arts stories all over the world and has interviewed artists including Marina Abramovic, Nan Goldin, Ai Weiwei, Lubaina Himid and Herzog & de Meuron. She has also worked in content strategy and production.

-

‘I’m surprised that I got this far’: Rick Owens on his bombastic Paris retrospective, ‘Temple of Love’

‘I’m surprised that I got this far’: Rick Owens on his bombastic Paris retrospective, ‘Temple of Love’The Dark Prince of Fashion sits down with Wallpaper* to discuss legacy, love, and growing old in Paris as a display at the Palais Galliera tells the story of his subversive career

-

2025 is Leica 1’s centenary year. The camera manufacturer is celebrating in style

2025 is Leica 1’s centenary year. The camera manufacturer is celebrating in styleA cavalcade of limited-edition Leica cameras is released to celebrate 100 years of the groundbreaking Leica 1

-

‘Her pictures looked like pictures everybody knew were the truth’: Diane Arbus at the Armory

‘Her pictures looked like pictures everybody knew were the truth’: Diane Arbus at the ArmoryMatthieu Humery curates more than 400 of Arbus’ photographs at New York’s Park Avenue Armory – every picture she was known to have printed

-

Vincent Van Gogh and Anselm Kiefer are in rich and intimate dialogue at the Royal Academy of Arts

Vincent Van Gogh and Anselm Kiefer are in rich and intimate dialogue at the Royal Academy of ArtsGerman artist Anselm Kiefer has paid tribute to Van Gogh throughout his career. When their work is viewed together, a rich relationship is revealed

-

Alice Adams, Louise Bourgeois, and Eva Hesse delve into art’s ‘uckiness’ at The Courtauld

Alice Adams, Louise Bourgeois, and Eva Hesse delve into art’s ‘uckiness’ at The CourtauldNew exhibition ‘Abstract Erotic’ (until 14 September 2025) sees artists experiment with the grotesque

-

Get lost in Megan Rooney’s abstract, emotional paintings

Get lost in Megan Rooney’s abstract, emotional paintingsThe artist finds worlds in yellow and blue at Thaddaeus Ropac London

-

Out of office: the Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: the Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekIt was a jam-packed week for the Wallpaper* staff, entailing furniture, tech and music launches and lots of good food – from afternoon tea to omakase

-

London calling! Artists celebrate the city at Saatchi Yates

London calling! Artists celebrate the city at Saatchi YatesLondon has long been an inspiration for both superstar artists and newer talent. Saatchi Yates gathers some of the best

-

Alexandra Metcalf creates an unsettling Victorian world in London

Alexandra Metcalf creates an unsettling Victorian world in LondonAlexandra Metcalf turns The Perimeter into a alternate world in exhibition, 'Gaaaaaaasp'

-

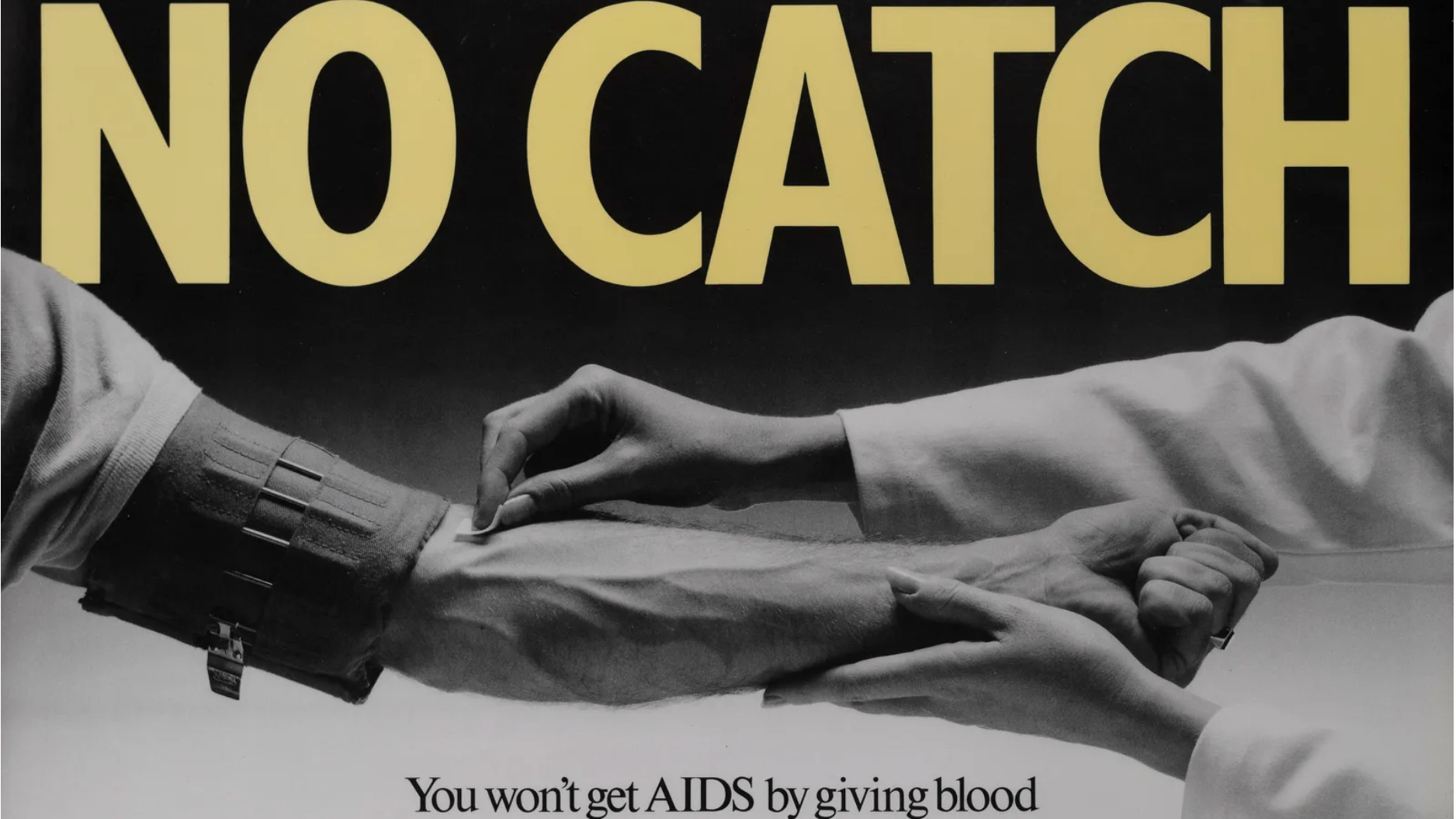

Sexual health since 1987: archival LGBTQIA+ posters on show at Studio Voltaire

Sexual health since 1987: archival LGBTQIA+ posters on show at Studio VoltaireA look back at how grassroots movements emphasised the need for effective sexual health for the LGBTQIA+ community with a host of playful and informative posters, now part of a London exhibition

-

Ten things to see at London Gallery Weekend

Ten things to see at London Gallery WeekendAs 125 galleries across London take part from 6-8 June 2025, here are ten things not to miss, from David Hockney’s ‘Love’ series to Kayode Ojo’s look at the superficiality of taste