'I want to get into these images and perfume them': Linder's retrospective opens at the Hayward Gallery

'Linder: Danger Came Smiling' gathers fifty years of the artist's work at the Hayward Gallery. We meet the punk provocateur ahead of her first retrospective

I meet Linder at the cafe at the Hayward Gallery, on the opening day of her - surprisingly – first London retrospective. She’s dressed for battle, or for protection, in a glittering Ashish top that lends her a reassuring physical weight. (‘It’s like those weighted blankets in a way. I feel invincible! Not that I’m under attack,’ she says, as we say hello.)

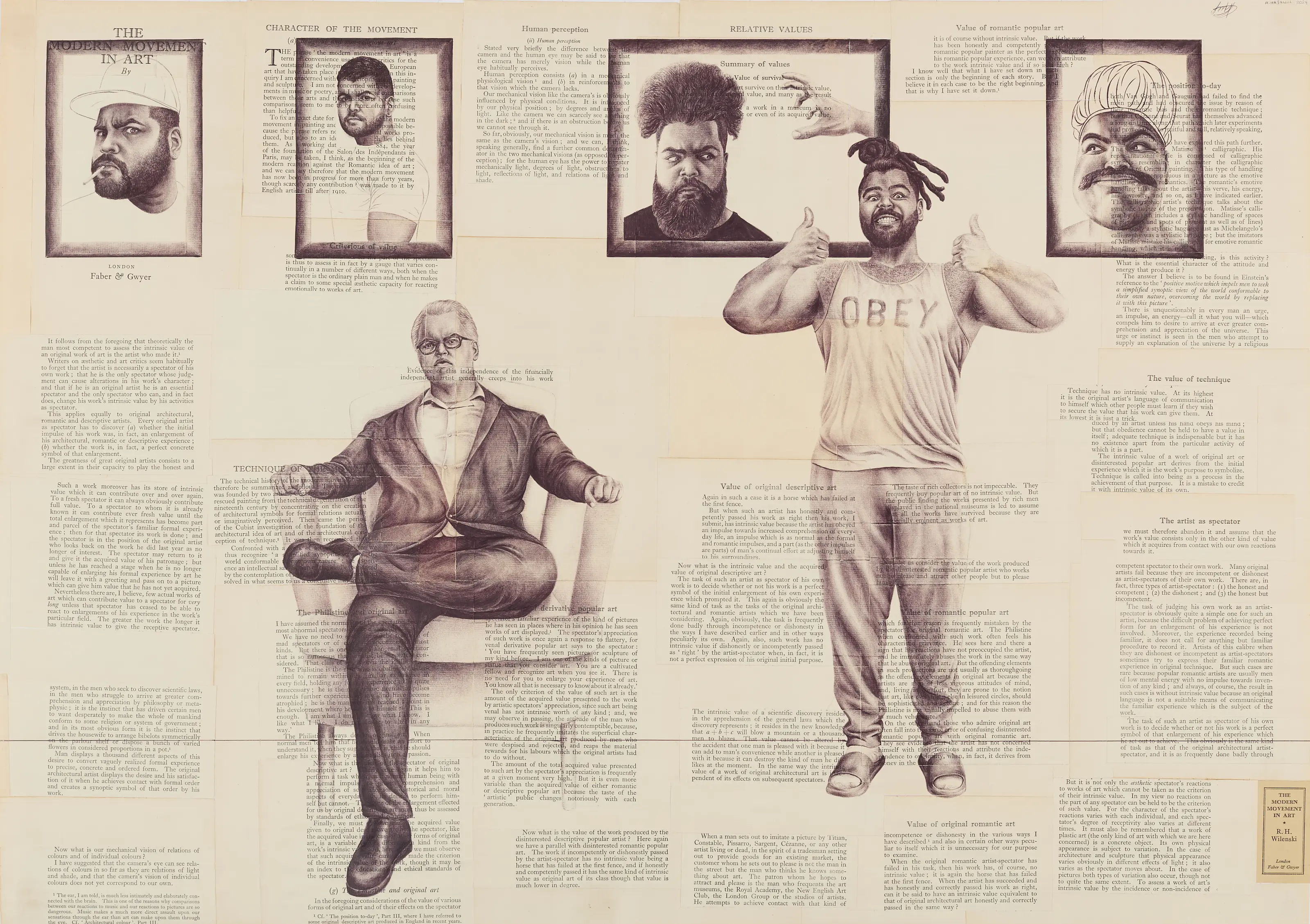

It’s a big moment for the Liverpool-born artist, who is marking her seventieth year with a fifty-year multidisciplinary retrospective. Tracing her beginnings on the punk music scene, via her photomontages and eclectic embrace of references, from pornography to fashion, ballet, fetish, weightlifting and art history, it culminates with her newest pieces, deepfake images of herself.

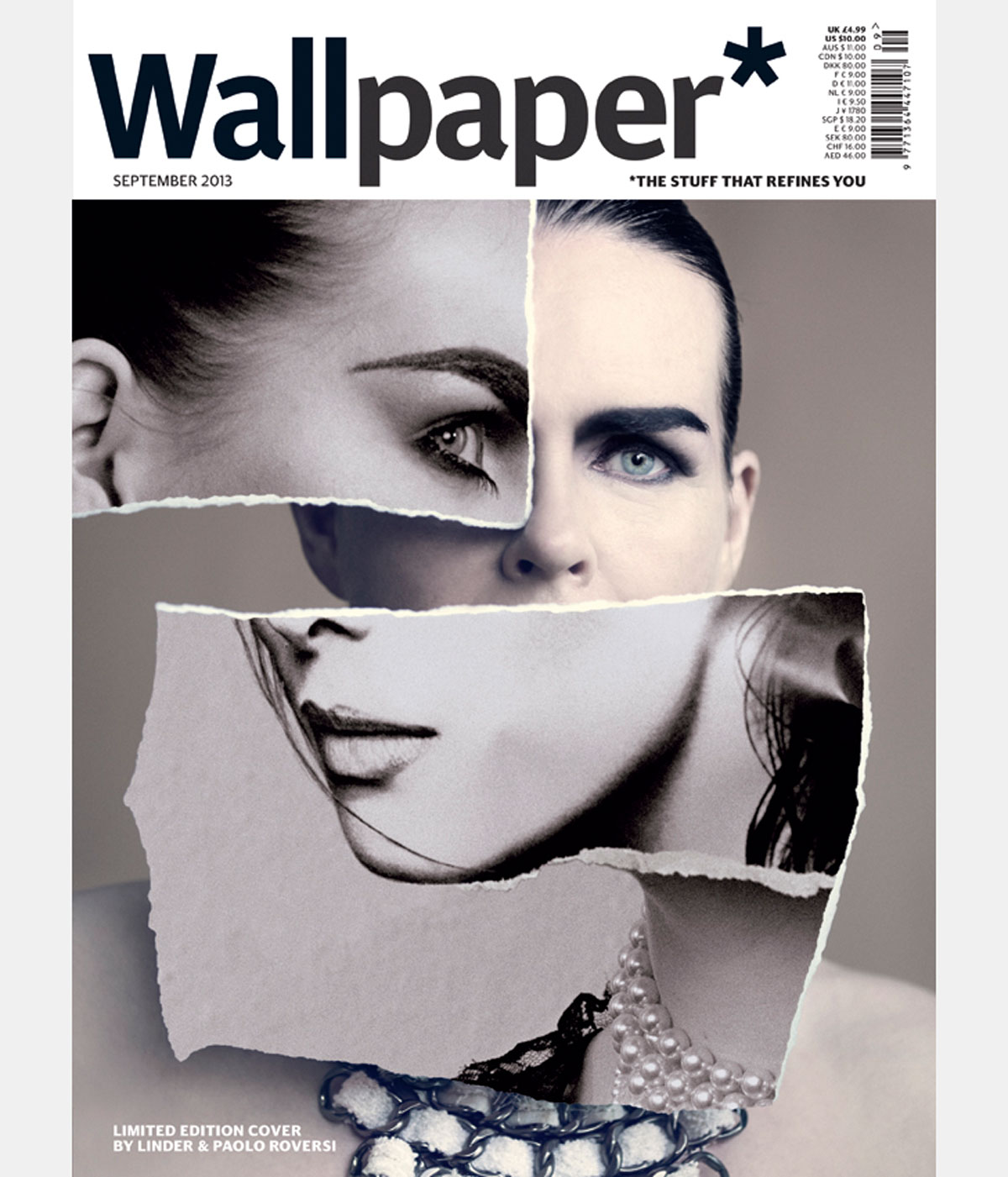

Linder's September 2013 Wallpaper* cover, created in collaboration with Paolo Roversi and Isabelle Kountoure

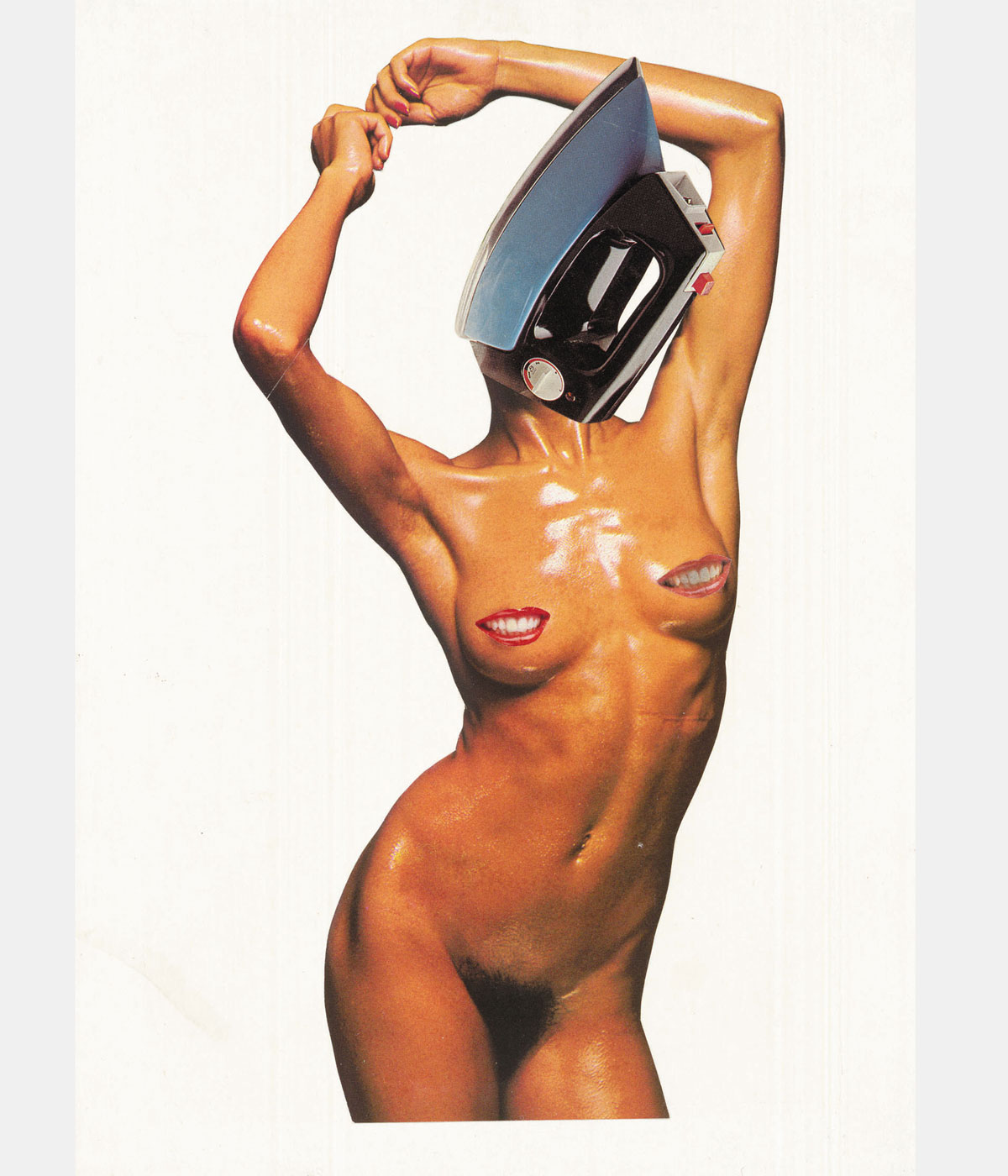

Untitled, Linder, 1976. Tate, purchased 2007. © Linder. Photo: Tate.

Taking centre stage here is arguably her most well-known work, the photomontage she created in 1977 for the cover of Buzzcocks’ debut single ‘Orgasm Addict’, which cemented her place in the punk and post-punk landscape. At the time, she was studying graphic design at Manchester Polytechnic, exploring the art of photomontage, drawn to magazine images depicting ‘women’s interests’ - the home, fashion, romance - which she juxtaposed against men’s (pornography, DIY, cars).

Using a surgical scalpel, Linder literally slices through these stereotypes in fluid pastiches that criss-cross conventional gender roles, turning the male gaze on its head while her subjects’ lose theirs. Depicting a naked woman with smiling mouths on her breasts and an iron where her head should be, the image is both playful and disturbing. Confronting and celebrating the glamour inherent in the representation of the female body, Linder mischievously recontextualises it again, delighting in contrasts, an impulse which runs throughout all of her work.

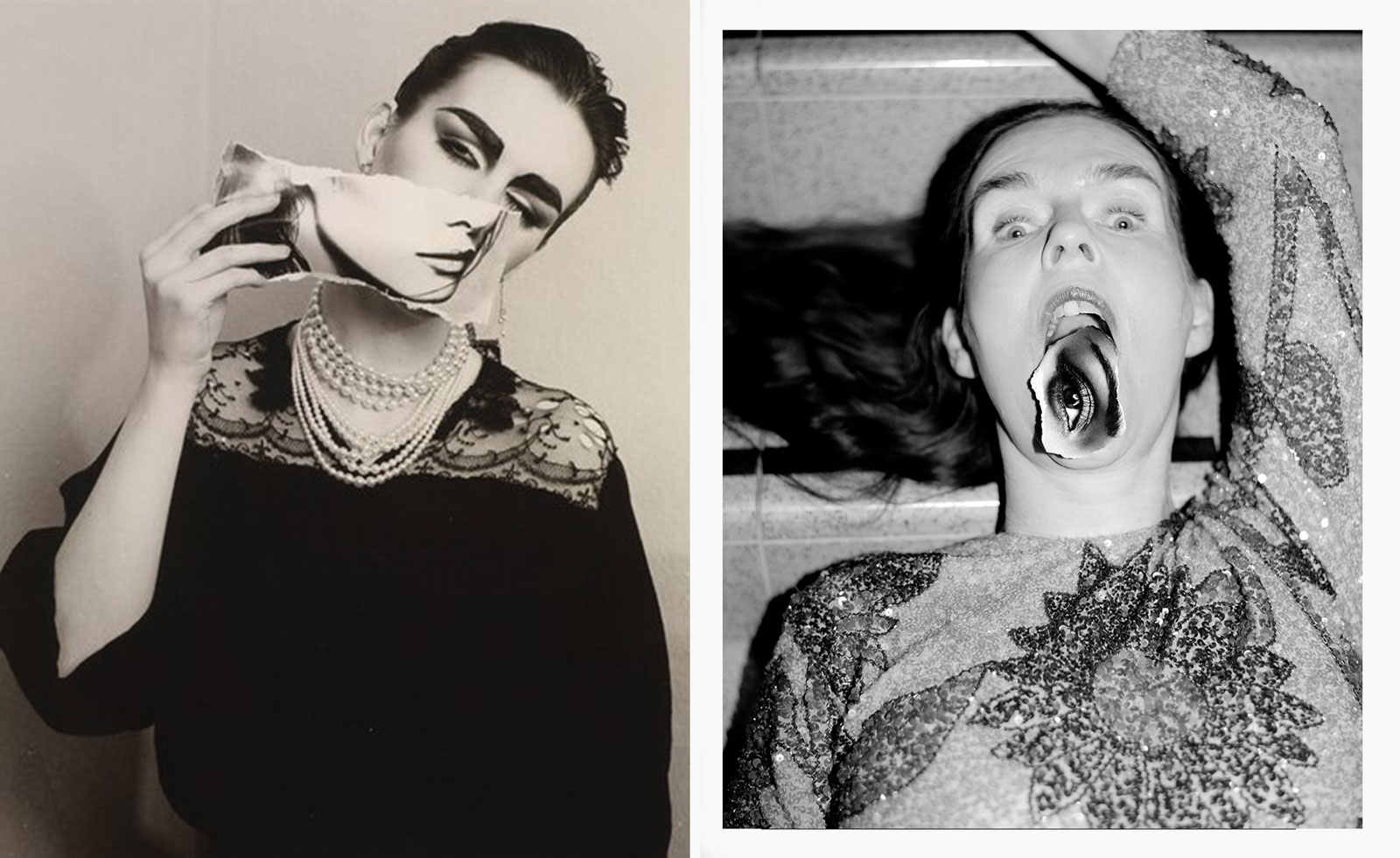

Linder's shoot for the September 2013 issue of Wallpaper*, created in collaboration with Paolo Roversi and Isabelle Kountoure

Linder at the Hayward Gallery. Photo: Hazel Gaskin. Outfit: Ashish. Make-up: Kristina Ralph Andrews. Courtesy the artist and Hayward Gallery.

‘There is a mischievousness sometimes in placing one huge caterpillar or a cucumber over the genital area,’ she says. ‘There is almost a childlike glee, but then it's also a critique - it’s a gag, a joke, but a gag is also a word with many meanings. I like the good ‘gag,’ while at the same time being aware that those models are gaps. We don't know who they are because they're never allowed to speak. They're always anonymous. It’s witty, having a light touch with often quite disturbing material that is so exploitative of other subjects. I’m from Liverpool - making jokes is in the DNA.’

There’s a warmth in Linder’s work, seen not only in the recontextualisation of occasionally alarming imagery and in her celebration of women’s bodies and queer bodies but also in her elevation of the mundane objects which make up a life. ‘It's all about this elevation, revering that photograph taken in 1976, where she [the subject] would have had to do about 20 different poses. There’s an empathy almost in trying to travel back and adding flowers, or a bouquet, like one would to a ballet dance stage, getting into those images to perfume them.’

Linder's shoot for the September 2013 issue of Wallpaper*, created in collaboration with Paolo Roversi and Isabelle Kountoure

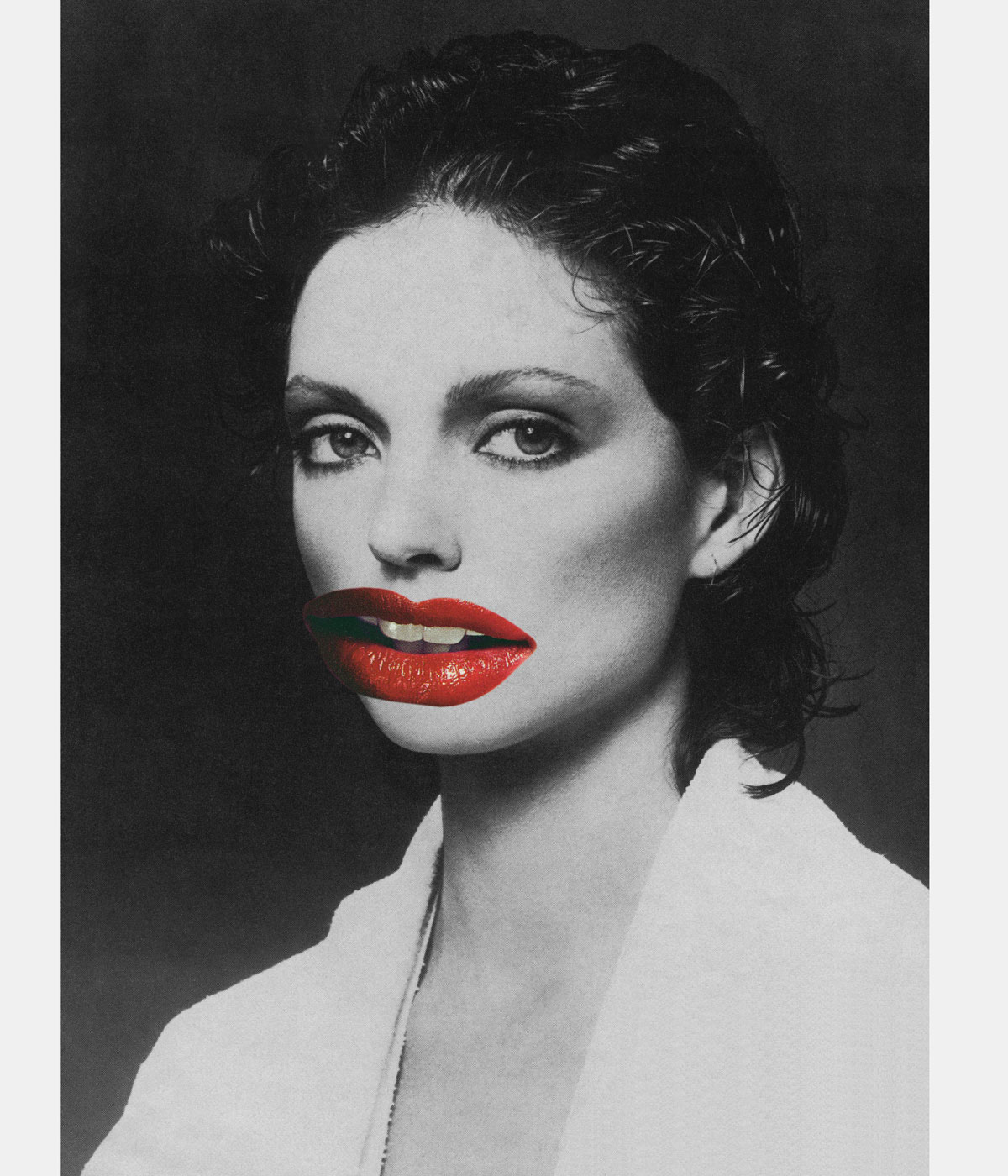

Linder, Untitled, 1979. © Linder Sterling. Courtesy of the artist; Modern Art, London; BLUM, Los Angeles, Tokyo, New York; Andréhn-Schiptjenko, Stockholm, Paris and dépendance, Brussels

Linder has spoken before about being exposed to pornography from the age of three by her grandfather, who also subjected her to sexual assault. ‘With this pornography, and maybe for me, I think because I was little, I'd always be looking at their faces. I didn't really want to be looking at the bodies. And I think maybe - this is the first time I’ve thought this - maybe that's circling back, and now I can lay them to rest. I can make them really tender.’ In cutting out the heads in her own work, Linder is protecting these women, with domestic utensils often thought to encumber women here making them mighty, cyborg-like, ready for battle.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Many moments in the exhibition are tender, often surprisingly so, particularly in the tribute she pays to her late father with a series of photographs of herself and a friend ‘sploshing’ - the fetishistic practice of using food in a playful, messy and sexual way. In the intertwining of fetish and desire, tenderness and deep love, it is yet another uniting of two states which perhaps aren’t as antithetical as they may at first appear to be.

Installation view of Linder: Danger Came Smiling. L-R: Danse Sacrale (L'Élue) (2011); Action Rituelle des Ancêtres (2011); Glorification de l'Élue (2011). Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy the artist and the Hayward Gallery.

‘I was very close to my father, he was so active at 84, and then he had a stroke. It was cruel. To keep his dignity in hospital, I used to feed him sweet, institutional food, like custard and yoghurt. After he died, I was aware of sploshing, which seems very British English in a way, it couldn’t ever have come from any other country, this fetish where women are covered in fake beans, head to toe. So to do that, in a session with a close friend, was so cathartic. Tin upon tin of custard, rice pudding, food colouring, honey, yogurt, cream, head to toe. It was incredible, really, and moving. We don't really have rights of passage anymore. So I was really happy with showing it here, really blown up so you can see every grain of rice. At that time I was bloated with tears, I couldn't cry. So that felt good too.’

Throughout fifty years of work is Linder’s love for print. ‘There's more than a century of print media in the show. We do get some idea that print media itself is never static, the technology is always evolving. I love playing with the materiality of print, and its smell and texture. Pixels have no perfume.’

'Linder: Danger Came Smiling' is at the Hayward Gallery, London, until 5 May 2025

Hannah Silver is the Art, Culture, Watches & Jewellery Editor of Wallpaper*. Since joining in 2019, she has overseen offbeat art trends and conducted in-depth profiles, as well as writing and commissioning extensively across the worlds of culture and luxury. She enjoys travelling, visiting artists' studios and viewing exhibitions around the world, and has interviewed artists and designers including Maggi Hambling, William Kentridge, Jonathan Anderson, Chantal Joffe, Lubaina Himid, Tilda Swinton and Mickalene Thomas.

-

Like a modernist iceberg, this Krakow house has a perfectly chiselled façade

Like a modernist iceberg, this Krakow house has a perfectly chiselled façadeA Krakow house by Polish architecture studio UCEES unites brutalist materialities with modernist form

-

Leo Costelloe turns the kitchen into a site of fantasy and unease

Leo Costelloe turns the kitchen into a site of fantasy and uneaseFor Frieze week, Costelloe transforms everyday domesticity into something intimate, surreal and faintly haunted at The Shop at Sadie Coles

-

Can surrealism be erotic? Yes if women can reclaim their power, says a London exhibition

Can surrealism be erotic? Yes if women can reclaim their power, says a London exhibition‘Unveiled Desires: Fetish & The Erotic in Surrealism, 1924–Today’ at London’s Richard Saltoun gallery examines the role of desire in the avant-garde movement

-

Leo Costelloe turns the kitchen into a site of fantasy and unease

Leo Costelloe turns the kitchen into a site of fantasy and uneaseFor Frieze week, Costelloe transforms everyday domesticity into something intimate, surreal and faintly haunted at The Shop at Sadie Coles

-

Can surrealism be erotic? Yes if women can reclaim their power, says a London exhibition

Can surrealism be erotic? Yes if women can reclaim their power, says a London exhibition‘Unveiled Desires: Fetish & The Erotic in Surrealism, 1924–Today’ at London’s Richard Saltoun gallery examines the role of desire in the avant-garde movement

-

Tiffany & Co’s artist mentorship at Frieze London puts creative exchange centre stage

Tiffany & Co’s artist mentorship at Frieze London puts creative exchange centre stageAt Frieze London 2025, Tiffany & Co partners with the fair’s Artist-to-Artist initiative, expanding its reach and reaffirming the value of mentorship within the global art community

-

Em-Dash is a small press redefining the indie zine beyond nostalgia

Em-Dash is a small press redefining the indie zine beyond nostalgiaThe South London publishing studio's new imprint 'Practice Meets Paper' translates a chosen artist’s practice into print. Wallpaper*s senior designer Gabriel Annouka speaks with the founders, Saundra Liemantoro and Aarushi Matiyani, to find out more

-

‘It is about ensuring Africa is no longer on the periphery’: 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair in London

‘It is about ensuring Africa is no longer on the periphery’: 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair in LondonThe 13th edition of 1-54 London will be held at London’s Somerset House from 16-19 October; we meet founder Touria El Glaoui to chart the fair's rising influence

-

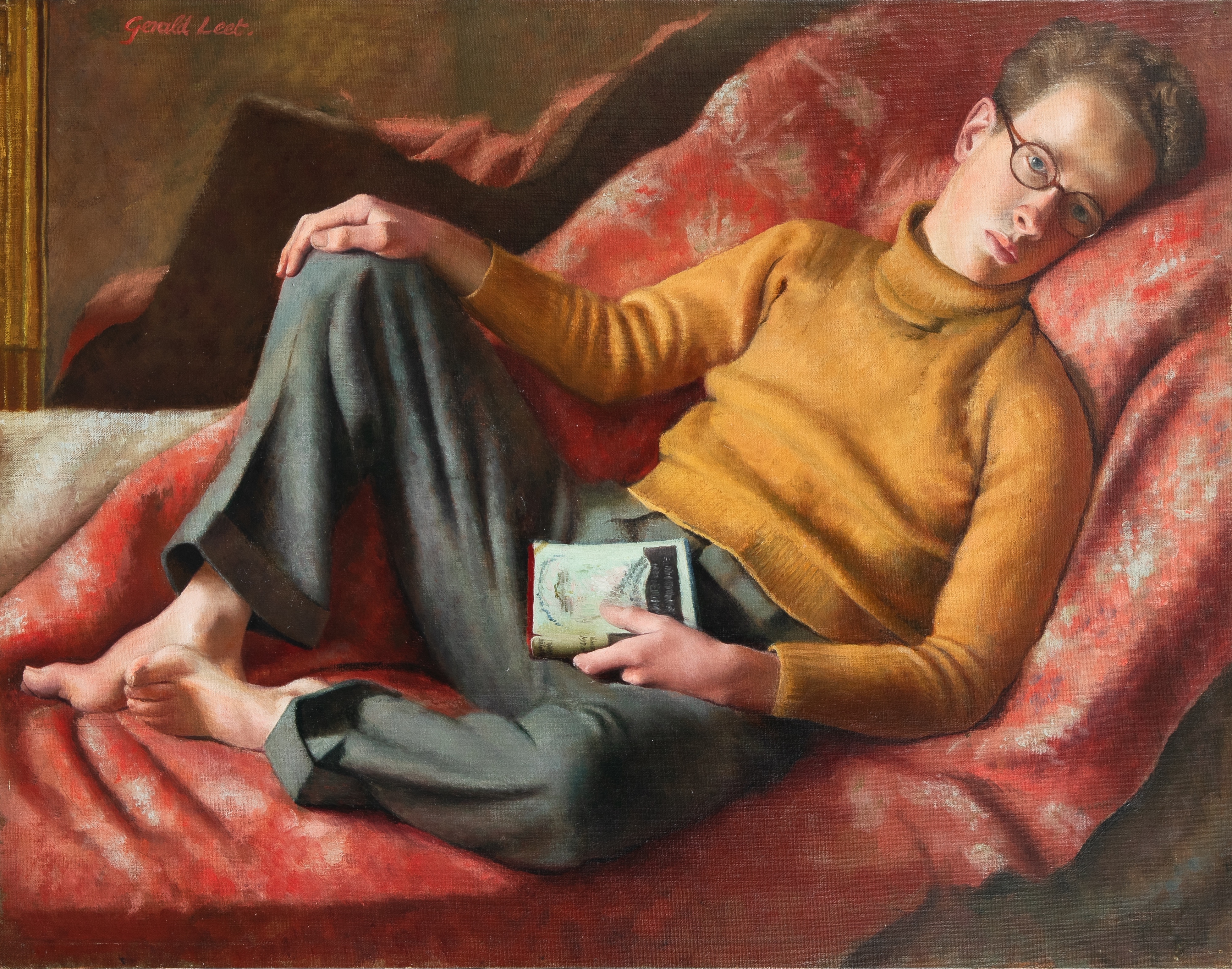

‘Sit, linger, take a nap’: Peter Doig welcomes visitors to his Serpentine exhibition

‘Sit, linger, take a nap’: Peter Doig welcomes visitors to his Serpentine exhibitionThe artist’s ‘House of Music’ exhibition, at Serpentine Galleries, rethinks the traditional gallery space, bringing in furniture and a vintage sound system

-

Who was Denton Welch, the cult writer and painter who inspired everyone from Alan Bennett to William S. Burroughs?

Who was Denton Welch, the cult writer and painter who inspired everyone from Alan Bennett to William S. Burroughs?Cult queer figure Denton Welch was a talented, yet overlooked, artist. Now an exhibition of his work at John Swarbrooke Fine Art aims to change that

-

Frieze Sculpture is back – here's what to see in Regent's Park

Frieze Sculpture is back – here's what to see in Regent's ParkFrieze Sculpture has returned to Regent's Park. As London gears up for Art Week, here's what to see on the fringes