Nan Goldin takes over London’s Welsh Chapel with a provocative new film

Nan Goldin’s ‘Sisters, Saints, Sibyls’ – at The Welsh Chapel, London until 23 June 2024 as part of Gagosian Open – is not an easy watch

At age 12, Barbara, the elder sister of pioneering photographer Nan Goldin, was admitted to a psychiatric centre. The given reasons for her institutionalisation were her sexually provocative behaviour and refusal to shave her legs, amongst many others. As a witness to Barbara’s physical and psychological abuse and her eventual suicide, Goldin ran away from home and found solace amongst a group of fellow rebels before succumbing to an opioid addiction. Now consecrating all this to film, her latest presentation with Gagosian, ‘Sisters, Saints, Sibyls’, opens in London’s former Welsh Chapel, in Soho, until 23 June 2024.

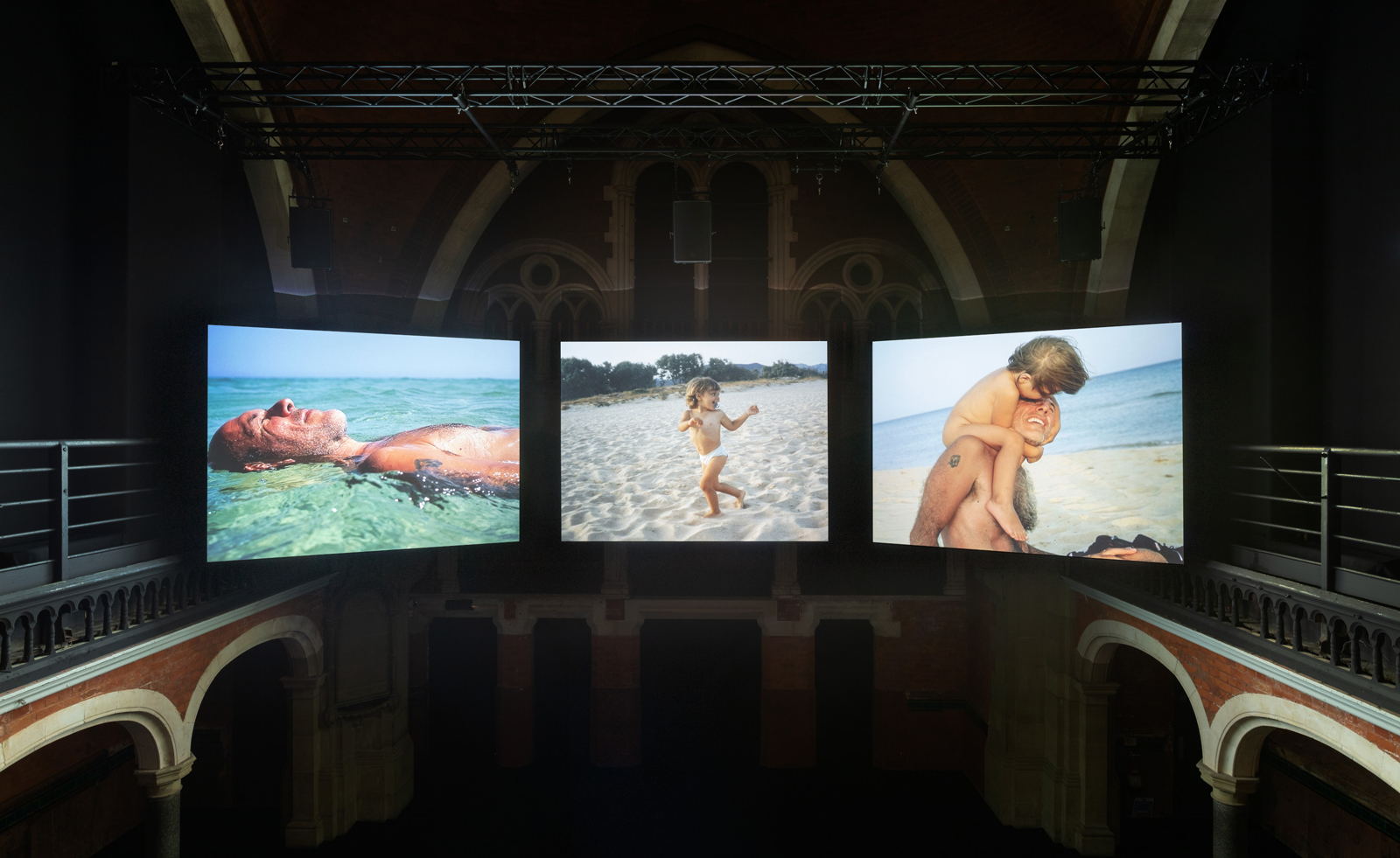

Goldin is a meticulous archivist, and ‘Sisters, Saints, Sibyls’ features a slideshow of photos from her life overlaid by stoic narration. Taking form through a three-channel projection redolent of Byzantine and Christian triptychs, the film opens with the story of early Christian martyr Saint Barbara, beheaded by her father for finding liberation through spirituality. The saint's story offers a useful rubric for interpreting the rest of the piece, particularly where Barbara Goldin’s story is concerned.

Nan Goldin’s ‘Sisters, Saints, Sibyls’ evinces a link between spiritual and psychiatric abuse

The Welsh Chapel, London

Originally conceived in 2004 for the chapel of the Hôpital de la Salpêtrière in Paris – a former asylum where Jean-Martin Charcot conducted experiments on ‘hysteric women’ – the film implicitly lays bare the tensions of religious idealism and the Church’s difficult past. Even Goldin’s rehab centre, the focus of the film’s final section, eerily resembles a church. Her deadening descent into addiction and self-harm don’t make for an easy watch, but not much of the film does.

Alongside her totemic art career, Goldin’s intransigent campaign against the billionaires fuelling the US opioid epidemic has positioned her as one of the art world’s most powerful figures. Her dedication extends to addressing social injustice through the AIDS crisis and reproductive rights, earning her the title 'portraitist of souls'. Here, ‘Sisters, Saints, Sibyls’ accords femininity a sanctified vindication.

Nan Goldin, ‘Sisters, Saints, Sibyls’, 2024, installation view

As the film evinces a link between spiritual and psychiatric abuse, the Welsh Chapel offers up an opulent setting for meaningful dialogue about religion’s historically oppressive treatment of women and their sexuality. It’s wise, then, to remember that Magdalene laundries, exorcisms, and conversion therapy are some of the other ways that the Church has inflicted profound psychological harm under the guise of moral and spiritual guidance. Can true faith ever be divorced from this legacy, Goldin, the child of middle-class Jewish parents, seems to ask. While there's no easy answer to this, ‘Sisters, Saints, Sibyls’ certainly makes the case for searching for one.

Nan Goldin, 'Sisters, Saints, Sibyls’, is at The Welsh Chapel, Gagosian Open, until 23 June 2024

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Nan Goldin, ‘Sisters, Saints, Sibyls’, 2024, installation view

Katie Tobin is a culture writer and a PhD candidate in English at the University in Durham. She is also a former lecturer in English and Philosophy.

-

Alexander Wessely turns the Nobel Prize ceremony into a live artwork

Alexander Wessely turns the Nobel Prize ceremony into a live artworkFor the first time, the Nobel Prize banquet has been reimagined as a live artwork. Swedish-Greek artist and scenographer Alexander Wessely speaks to Wallpaper* about creating a three-act meditation on light inside Stockholm City Hall

-

At $31.4 million, this Lalanne hippo just smashed another world auction record at Sotheby’s

At $31.4 million, this Lalanne hippo just smashed another world auction record at Sotheby’sThe jaw-dropping price marked the highest-ever for a work by François-Xavier Lalanne – and for a work of design generally

-

NYC’s first alcohol-free members’ club is full of spirit

NYC’s first alcohol-free members’ club is full of spiritThe Maze NYC is a design-led social hub in Flatiron, redefining how the city gathers with an alcohol-free, community-driven ethos

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the weekThis week, the Wallpaper* editors curated a diverse mix of experiences, from meeting diamond entrepreneurs and exploring perfume exhibitions to indulging in the the spectacle of a Middle Eastern Christmas

-

A London exhibition celebrates the next generation of Ukrainian photographers

A London exhibition celebrates the next generation of Ukrainian photographersFUTURESPECTIVE at Saatchi Gallery presents an intimate portrait of a country in the midst of conflict

-

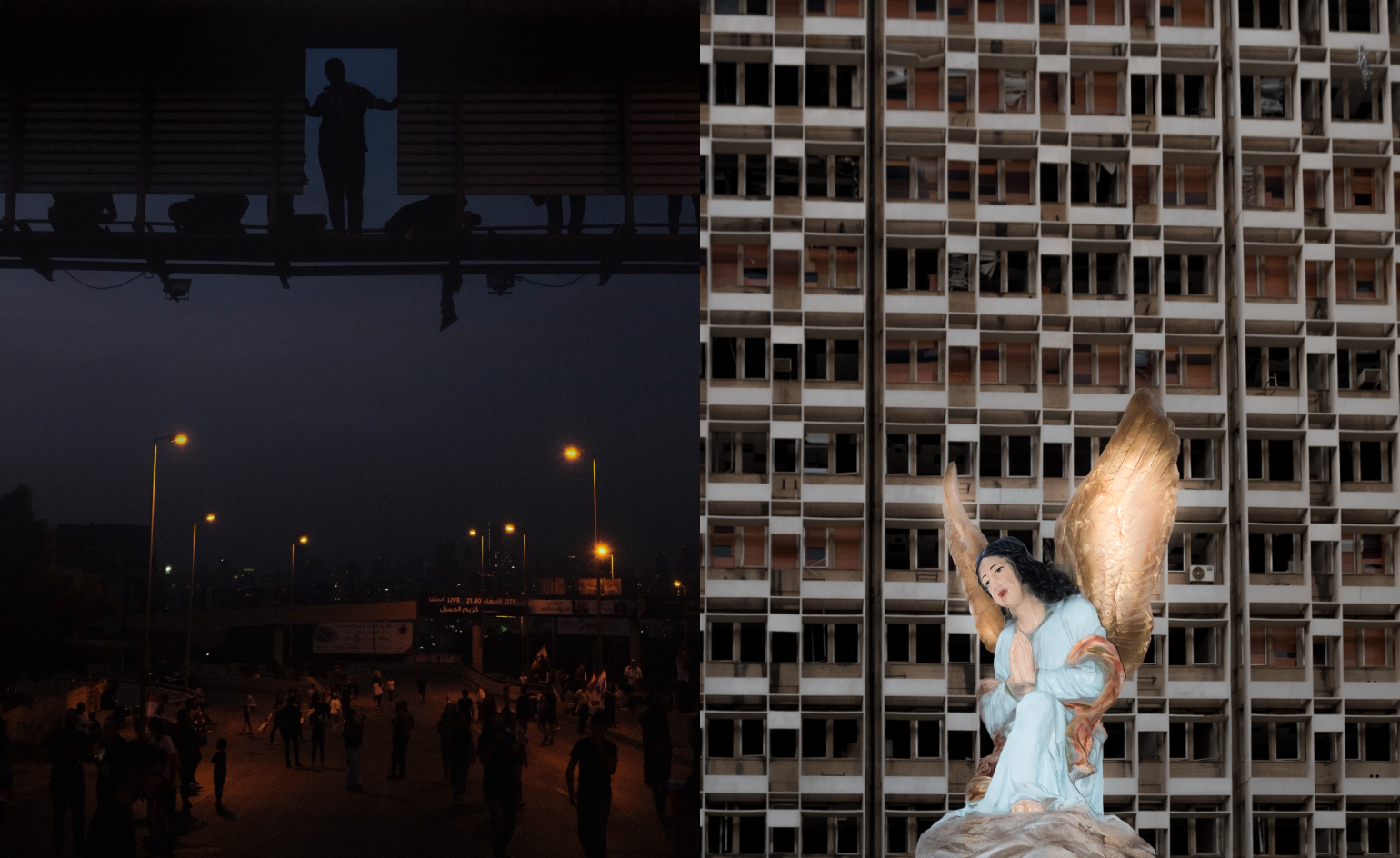

A poignant Lebanese photo book reflects on the memory of home

A poignant Lebanese photo book reflects on the memory of homeCharbel Alkhoury conveys the ache of seeking asylum in a photography book that documents not just a place, but its lingering afterimage

-

Rolf Sachs’ largest exhibition to date, ‘Be-rühren’, is a playful study of touch

Rolf Sachs’ largest exhibition to date, ‘Be-rühren’, is a playful study of touchA collection of over 150 of Rolf Sachs’ works speaks to his preoccupation with transforming everyday objects to create art that is sensory – both emotionally and physically

-

From activism and capitalism to club culture and subculture, a new exhibition offers a snapshot of 1980s Britain

From activism and capitalism to club culture and subculture, a new exhibition offers a snapshot of 1980s BritainThe turbulence of a colourful decade, as seen through the lens of a diverse community of photographers, collectives and publications, is on show at Tate Britain until May 2025

-

Dark, glamorous and hedonistic: a photography book captures New York in the 1990s

Dark, glamorous and hedonistic: a photography book captures New York in the 1990sNew York: High Life, Low Life, by Dafydd Jones, goes behind the scenes of New York society

-

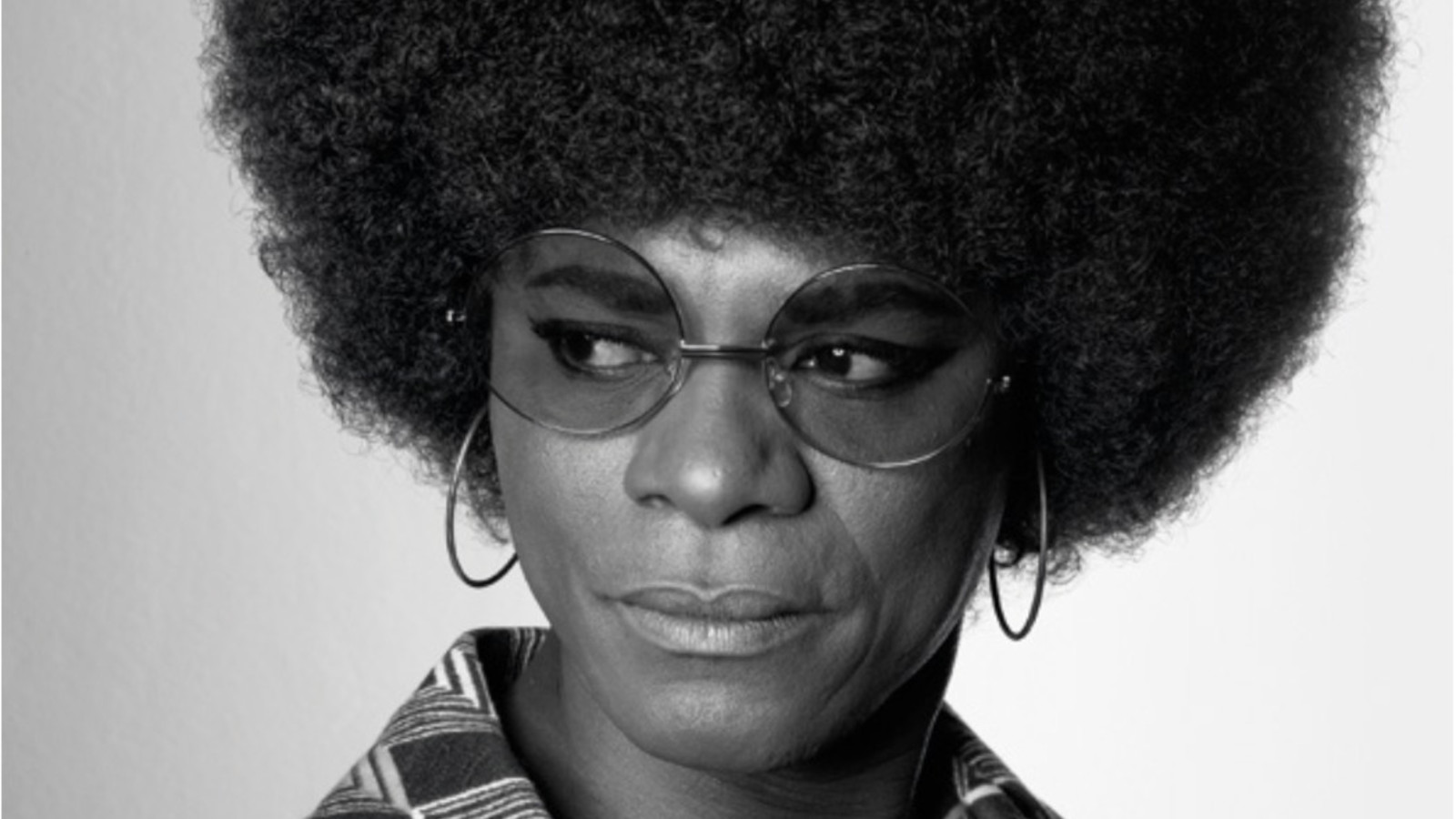

Samuel Fosso wins Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2023

Samuel Fosso wins Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2023Samuel Fosso is announced winner of the Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2023; see his work, and that of all the nominees at The Photographers' Gallery, London

-

Elder Sex: Marilyn Minter’s steamy new photo book spotlights intimacy in older age

Elder Sex: Marilyn Minter’s steamy new photo book spotlights intimacy in older ageArtist Marilyn Minter’s bold, body-positive new photo book, Elder Sex, is an unbridled exploration of sex after the age of 70