Pino Pascali’s brief and brilliant life celebrated at Fondazione Prada

Milan’s Fondazione Prada honours Italian artist Pino Pascali, dedicating four of its expansive main show spaces to an exhibition of his work

‘Live fast, die young’ does tend to create a legend. Italian artist Pino Pascali exhibited for only four years before being killed in a motorbike crash, aged 32, in 1968. Yet today, Fondazione Prada in Milan has dedicated four of its extensive main show spaces to an exhibition honouring his work.

Born in Bari in 1935, Pascali graduated in stage design and sculpture at Rome’s Accademia di Belle Arti in 1959. Miuccia Prada writes in the exhibition catalogue’s introduction of his ‘inexhaustible instinct to rethink’. The Fondazione show’s curator Mark Godfrey, an art historian formerly at Tate, says that Pascali ‘wanted to get away from the idea of a signature style, reinventing his art after each major public outing. He once compared himself to a snake shedding his skin.’ He did have a style though, albeit a serpentine one, which this generous exhibition lets speak for itself. Spread throughout the sensational Rem Koolhaas-designed complex, the first part recreates his solo shows, the second is an examination of his materials, the third a conversational exercise alongside works by his peers, and the fourth a sequence of his most extroverted installations set against XL portraits of the no less performative artist himself posing by each with comedic verve.

Pino Pascali at Fondazione Prada: a pioneer remembered

Exhibition view of ‘Pino Pascali’, Fondazione Prada, Milan. In the foreground is Pascali’s Vedova blu, 1968, with a photograph by Claudio Abate of Pascali posing with the work

Walking through Pascali’s recreated solo shows side by side is superb. You encounter his exhibition-as-unified-installation technique that, while commonplace today, was Pascali’s innovation and, says Godfrey, ‘his most original contribution to contemporary art’. His first solo show was at Galleria La Tartaruga, in Rome in 1965: in this version, you meet idolised elements of Italian culture – the colosseum, columns, and the female body (maternalised and eroticised, here pregnant in puritanical white beside hyper-sexualised red lips) – mainly blanched out, wall-mounted scenographic almost-paintings of details from these theatrically focus-pulled icons. Fragments of ancient ruins and isolated female body parts become like logos. A little sad, but also light, thanks to the ironically naïve charm of Pascali’s prop-like renderings.

His second exhibition, at Galleria Gian Enzo Sperone, in Torino in 1966, showed large-scale weapons crowded into a room, as disconcerting at the time of the Vietnam war as the experience of being dwarfed by 3m guns and missiles up close is in today’s bloodthirsty geopolitical context. One visitor at Fondazione Prada whispered to his girlfriend, ‘I don’t want to get too close’, offering a spontaneous authentic commentary that Pascali would no doubt have appreciated. A father, holding the hand of his little girl, walked out of the room the instant he saw its contents.

Back to 1966, when later that same year, at Rome’s Galleria L’Attico, the artist showed something entirely opposite in aesthetic, but united by its use of forms to communicate something about human violence. If the weapons had all the subtlety of heavy metal, this L’Attico show was – and is in its replication – more ‘kid glove, iron fist’. A series of mat-white painted animal parts, some dinosaur-like, their primitivism rendered minimalist by his white-out technique and abstracting dissection, greets you as sugary. It’s so simple and pretty, it prompts delight. The creatures’ simplified representation is part plaster workshop, part nursery book in appearance, and gives these lobotomised beings an adorable and tragic character. Where are their other body parts? Wall-mounted or on plinths, these animal works bring the hunter’s trophy and colonial collector’s cabinet of curiosities to mind.

Pascali’s presentation is full of pathos and narrative while nevertheless being visually very lean to the point of looking chic. The pieces are made by stretching canvas over wood, in a technique cribbed from model airplanes. One he titled La decapitazione della scultura, nodding to his interest in reconfiguring sculpture as a medium. He called these pieces his ‘fake’ or ‘feigned’ sculptures, and they have something more of stage props to them than the lineage and formalism that sculpture historically carried, especially in Italy.

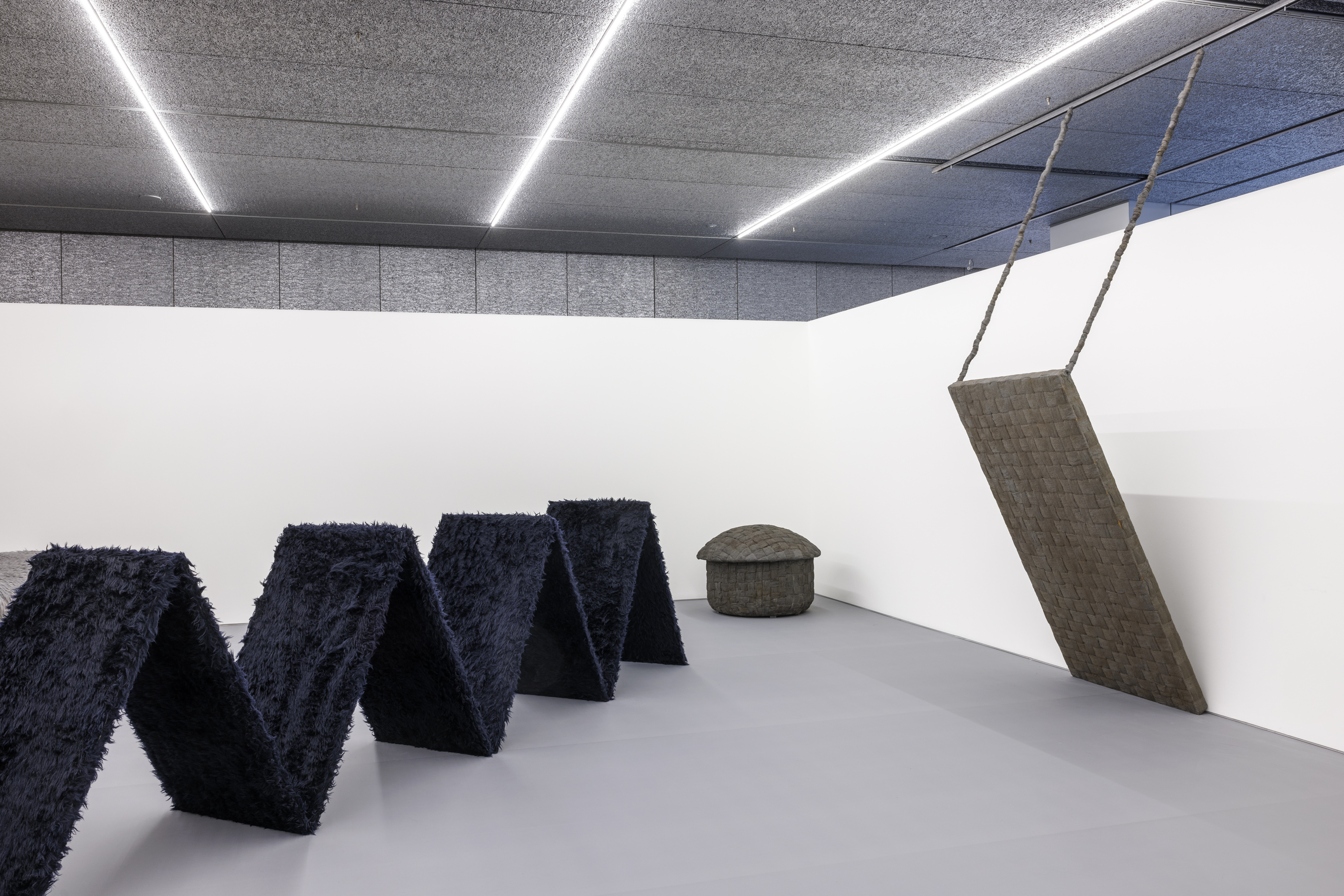

Exhibition view of ‘Pino Pascali’, Fondazione Prada, Milan. From left to right: Pino Pascali, Solitario, 1968; Il cesto, 1968; Archetipo o Ponte levatoio, 1968

Halfway through the ‘Animali’ exhibition, Pascali tried out a new trick he’d come up with – he de-installed the works and put new pieces in, creating a second half of the same show, amping up the theatricality that his objects already contained. Part two was a sculpture environment called The Sea, plus a giant black and white dolphin, which he later split in two and mounted either side of a wall so its body is disrupted, reinstalled at Fondazione Prada on a pillar. This piece is flamboyantly fun, with its violence intercepted by the visual impression that the creature is swimming through the wall – or is the wall slicing through the animal? It’s perfectly unclear.

From here, you step into a room containing a flat floor sculpture that drops the heart. Four concrete squares of pavement with removable central panels rest on a low plinth. Three of them have their central panels removed to reveal a turquoise puddle, grey gravel, and opaque black. Titled ‘trapdoors’ (botole), they remind you of the theatre of urban space and the environmental entombment that concrete enacts. Next door, Pascali suspended rope-like 3D hangings in wire wool, contrasting concrete’s rigid containment with their worming organic forms shaped into a net, bridge and creepers straight out of jungle movie set.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Exhibition view of ‘Pino Pascali’, Fondazione Prada, Milan. In foreground: Eliseo Mattiacci, Tubo, 1967

Upstairs in the materials section we meet oversized mushrooms and geometric shapes clad in more wire wool and retro fake fur in all its funky fabulosity. Giant rainbow caterpillars made of broom heads. Hay-bale geometry and ready-made impersonations of water and soil. It’s man-made meets nature. Industrial meets agricultural. Pre-digitally modern, conceptually tight, it’s Pascali’s own vision yet of its time, in intimate conversation with Arte Povera and Spatialism, as the vast room mixing his works with those of artists he exhibited alongside in group shows makes clear. Here Janis Kounellis’ blowtorch, metal and plexi Margherita di fuori rubs up alongside Alighiero Boetti’s aluminium and river rocks Panettone, set beside some Pascali. There’s also some amusing genius from Michelangelo Pistoletto and Piero Gilardi, and the relationships here enrich and contextualise the singular clarity of Pascali’s recreated solo shows.

One moment of peak 1960s Italianicity is portrayed by a black and white photo of a handsome, stocky, tousled Pascali leaning over a young woman (Michelle Coudray, long-term partner of Jannis Kounellis) wearing a Pucci mini dress as he looks into her eyes. Literally on the back foot, her bobbed-hair grazes the poultry feathers of his wall-mounted work Le penne d’Esopo at Venice Biennale, beside which his hand is resting territorially. He wears hippy leather sandals, a beatnik-y neckerchief, and a mod-ish silver chainmail belt, holding a cigarette that dates him further. Their body language tells you the picture is staged. Pascali, a consummate communicator, approached presenting his work with as much commitment as he did making it. He was clearly brilliant in the studio, but he was also gifted at framing the results in ways that captivated the public through his spirited style.

Pino Pascali, Colomba della Pace, 1965, artist’s studio, Rome. PhotoClaudio Abate © Archivio Claudio Abate

The Prada exhibition’s final section shows this to great effect as it places some of his strongest sculptures alongside black and white photographs of him posing in and around them, blown up to fill the walls, taken by his collaborators and friends. He did this so magazine editors would promote his shows as it made the images they received of his work stand out.

The most famous was taken by Claudio Abate, who shot Pascali upside down beneath his giant blue fake fur spider named Vedova blu, which he audaciously showed in a group show of mainly paintings. Like everything Pascali did, it was charismatic yet conceptual, ironic but sincere, evocative, accessible, low-tech, and quite brilliant. As Mark Godfrey and the Prada team’s poised and reverent tribute proves, Pascali’s all-in attitude sealed him a punchy place in art history’s memory.

‘Pino Pascali’ at the Fondazione Prada is on show until 23 September 2024

Kasia Maciejowska is a writer and editor covering arts and culture. Her first book The House of Beauty and Culture (ICA, 2016) was about a radical London crafts collective, and she’s currently working on a monograph about Moroccan-French photographer Leila Alaoui (Skira, 2026). Consultancy clients include museums, galleries, design studios, and futures agencies. She also runs a creative career mentoring network for young refugee women

-

Year in review: the shape of mobility to come in our list of the top 10 concept cars of 2025

Year in review: the shape of mobility to come in our list of the top 10 concept cars of 2025Concept cars remain hugely popular ways to stoke interest in innovation and future forms. Here are our ten best conceptual visions from 2025

-

These Guadalajara architects mix modernism with traditional local materials and craft

These Guadalajara architects mix modernism with traditional local materials and craftGuadalajara architects Laura Barba and Luis Aurelio of Barbapiña Arquitectos design drawing on the past to imagine the future

-

Robert Therrien's largest-ever museum show in Los Angeles is enduringly appealing

Robert Therrien's largest-ever museum show in Los Angeles is enduringly appealing'This is a Story' at The Broad unites 120 of Robert Therrien's sculptures, paintings and works on paper

-

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week

Out of office: The Wallpaper* editors’ picks of the week'Tis the season for eating and drinking, and the Wallpaper* team embraced it wholeheartedly this week. Elsewhere: the best spot in Milan for clothing repairs and outdoor swimming in December

-

The most comprehensive showing of Nan Goldin’s photographs and films is intense and emotional

The most comprehensive showing of Nan Goldin’s photographs and films is intense and emotionalNan Goldin's moving-image work makes a heavy impact in ‘This Will Not End Well’ at Milan’s Pirelli HangarBicocca

-

Yuko Mohri’s living installations play on Marcel Duchamp’s surrealism

Yuko Mohri’s living installations play on Marcel Duchamp’s surrealismThe artist’s seven new works on show at Milan’s Pirelli HangarBicocca explore the real and imaginary connections that run through society

-

What to expect from Thaddaeus Ropac’s new Milan gallery

What to expect from Thaddaeus Ropac’s new Milan galleryA stalwart among European galleries, Thaddaeus Ropac has chosen an 18th-century palazzo for its first venture into Milan

-

Rolf Sachs’ largest exhibition to date, ‘Be-rühren’, is a playful study of touch

Rolf Sachs’ largest exhibition to date, ‘Be-rühren’, is a playful study of touchA collection of over 150 of Rolf Sachs’ works speaks to his preoccupation with transforming everyday objects to create art that is sensory – both emotionally and physically

-

Architect Erin Besler is reframing the American tradition of barn raising

Architect Erin Besler is reframing the American tradition of barn raisingAt Art Omi sculpture and architecture park, NY, Besler turns barn raising into an inclusive project that challenges conventional notions of architecture

-

What is recycling good for, asks Mika Rottenberg at Hauser & Wirth Menorca

What is recycling good for, asks Mika Rottenberg at Hauser & Wirth MenorcaUS-based artist Mika Rottenberg rethinks the possibilities of rubbish in a colourful exhibition, spanning films, drawings and eerily anthropomorphic lamps

-

San Francisco’s controversial monument, the Vaillancourt Fountain, could be facing demolition

San Francisco’s controversial monument, the Vaillancourt Fountain, could be facing demolitionThe brutalist fountain is conspicuously absent from renders showing a redeveloped Embarcadero Plaza and people are unhappy about it, including the structure’s 95-year-old designer