Contemporary artist collective Poush takes over Château La Coste

Members of Poush have created 160 works, set in and around the grounds of Château La Coste – the art, architecture and wine estate in Provence

Florian Monfrini wordlessly takes white stones from a pile, places them into two wicker buckets attached to a wooden dowel, then hauls them up a gravel path to another spot, where he'll use them to build a ‘petite architecture’. A few days from now, he will move them again.

Visitors to Château La Coste in the south of France, might come to see monumental outdoor works by Damien Hirst and Louise Bourgeois, to eat at a Michelin-starred restaurant, to taste wines in a Jean Nouvel-designed cellar. An itinerant work by a local artist carrying stones on his back is not typically part of the programme. But now, two worlds collide, as artists from the Poush art centre in the northern suburbs of Paris temporarily occupy the Provençal wine estate and its 500 acres of pathways, grapevines, oak and olive trees, and architectural jewels.

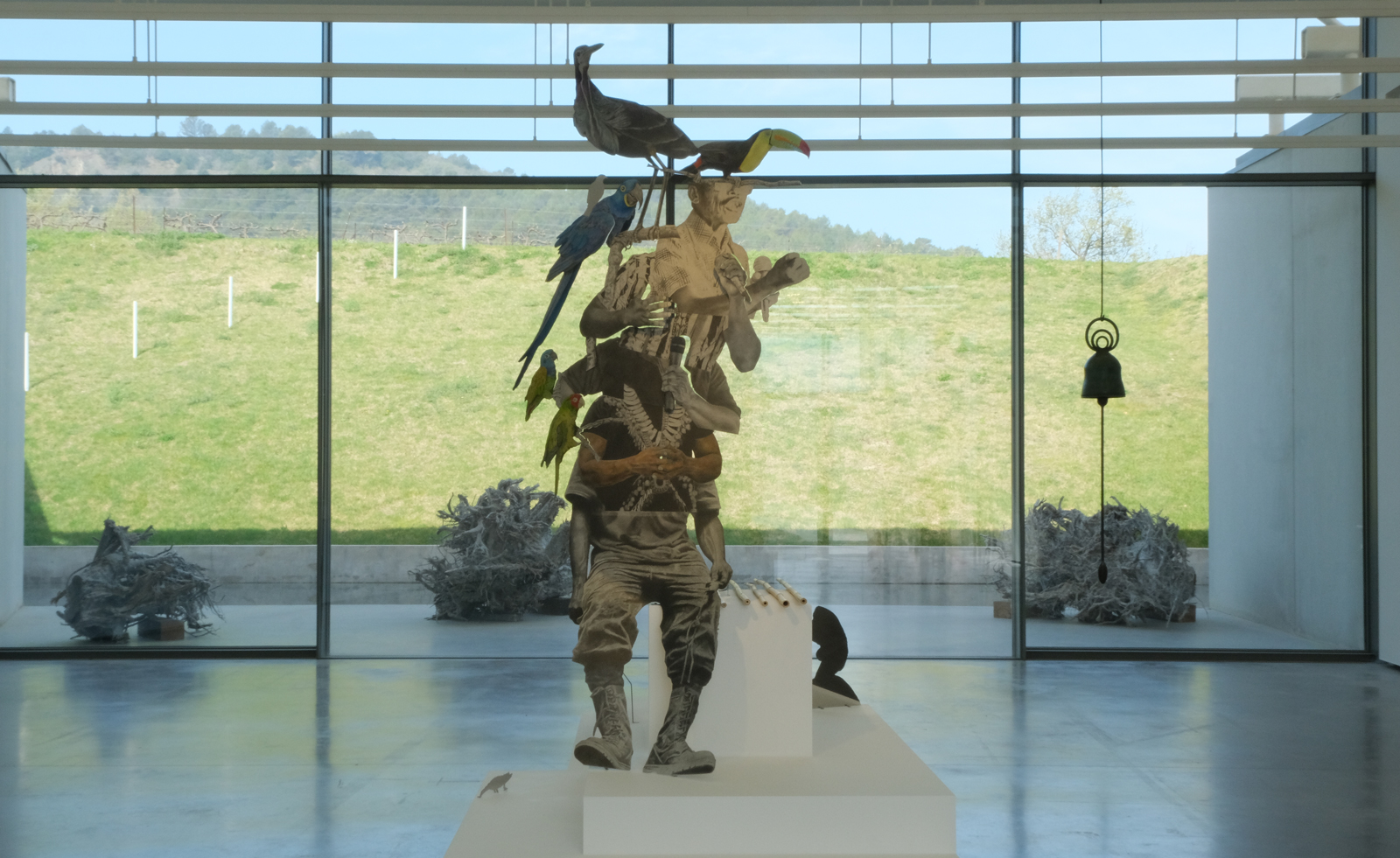

Work by Edgar Sarin, la Méditerranée collective

Poush was created in 2020 as a place to support contemporary creation. It currently comprises 270 artists from around the world, who pay a minimal rate to rent individual ateliers in a 22,000 sq m former perfume factory. The support also involves organising exhibitions in diverse places.

The current show at Château La Coste is called ‘Par Quatre Chemins’ – a nod to the name of Poush's closest metro stop in Aubervilliers, Paris, but also a French expression that means wandering rather than getting straight to the point. Poush's director, Yvannoé Kruger, says, ‘The artists were able to come and spend some time here [at Château La Coste], to get to know the locals, the quarries, the gardeners, to take the pulse of this landscape, to feel their way around and find the best way to insert themselves.’

Work by Sara Favriau

The show features 35 artists (most from Poush, though some, like Monfrini, were invited for the event), representing 14 nationalities. One hundred and sixty of their works are scattered around the property and inside the various pavilions. They play off the site's nature, geography, architecture, regional customs and history. Co-commisaire Margaux Knight says, ‘The work is very diverse, a counterweight to the big solo shows we're used to seeing here.’

Most were created or revisited for this exhibition, around a dozen of them in situ. For example, Henri Frachon's Sea of holes consists of circular cavities dug out of the ground, each one containing a natural element from the domain (for example, a portion of a tree trunk), anchored in the soil to resist any wild boar that might wander by.

At the entrance, in the shade of architect Tadao Ando's façade, stands Pauline Guerrier’s The Guardians, three totems she first made in Bénin, covered in cotton fabric dyed with local pigments, inspired by the Zangbeto traditional guardians of the night. ‘Here,’ says Guerrier, ‘they become the guardians of this domain and the exhibition,’ keeping any evil spirits away.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

Work by Justine Emard

Next to a Truism Bench by Jenny Holzer (a permanent installation), Sabine Mirlesse has hung a bell within a small grove of trees, its long clapper resting on a water-filled indent in the ground. Mirlesse originally created this piece elsewhere in the south of France, where she learned that residents resented ‘helicopter artists’ who come down from Paris to create works with no link to local culture. So she asked village elders about their stories, and was taken to a spring where a church bell was hidden, a practice used to protect them from being melted into munitions.

Château La Coste also features buildings by world-renowned architects. One is Oscar Niemeyer's curved auditorium (his final design to be realised), where several Poush artists are showing works. A fellow Brazilian, Marlon de Azambuja, took a book of photographs of gas tanks by the German duo Berne and Hilla Becher and carefully covered the images with reflective black marker. ‘At the beginning of modernism in Brazil, you have this idea of “eating” European influence and transforming it into your identity,’ the artist explains. ‘For me, it's important that a Brazilian hand reconstructed this patrimony, this very precise German photography.’

La Mediterannée, a trio that describes itself as an ‘exhibition-oriented research group’, has taken over Richard Rogers' spectacular cantilevered gallery (also this architect's last building) with a collection of works that respond to the idea of empty space. At one end, an imposing oak sculpture by Edgar Sarin soaks in a prime view of the landscape from what Sarin calls Rogers' ‘corridor on the void’.

Work by Florian Monfrini

A former wine cellar redesigned by Jean-Michel Wilmotte is lit dimly, like a grotto, by a video covering one entire wall. The video is Justine Emard’s Hyperphantasia, confronting ancient and state-of-the-art approaches to image-making. An AI tool constantly produces new ‘drawings’ from a database of paleolithic cave paintings from Chauvet Pont-d'Arc as well as encephalographic signals (EEGs) from astronauts dreaming in orbit.

Two large oil paintings hang on either side of the video. The hyperrealist canvases, by Dhewadi Hadjab, were first shown in the Saint-Eustache church in Paris. In each, a contemporary dancer's sweatpant-clad body is slung over a prie-dieu, or prayer chair, in a pose that recalls the Descent from the Cross, or classic paintings of religious ecstasy. ‘At Saint-Eustache, these hung near a painting by Rubens,’ notes Hadjab. ‘Here they are in a different kind of chapel, in dialogue with a video, which gives them another dimension.’

And in a sunken pavilion designed by Renzo Piano, one wall displays artist Sara Favriau’s Les Petits Riens, or ‘Little Nothings’, delicate objects found on the property that are usually overlooked – a bird’s feather, a bottle cap – but here exhibited like tiny relics. Outside on the terrace, Angela Jiménez Durán has done the opposite, unearthing huge tree stumps on the property, cleaning the earth from the roots, and enveloping them in wax. ‘I wanted to create a portrait of the landscape underground, and these roots we don't see,’ says Durán. ‘By transforming, or “frosting” them with paraffin, I'm giving shape to objects that are no longer alive, that we don't consider important, but which still have an existence and a presence.’ As she reminds us, not all the sculptures on this land are man-made.

‘Par Quatre Chemins’ runs until 9 June 2025 at Château La Coste, France, chateau-la-coste.com

-

Ligne Roset teams up with Origine to create an ultra-limited-edition bike

Ligne Roset teams up with Origine to create an ultra-limited-edition bikeThe Ligne Roset x Origine bike marks the first venture from this collaboration between two major French manufacturers, each a leader in its field

By Jonathan Bell

-

The Subaru Forester is the definition of unpretentious automotive design

The Subaru Forester is the definition of unpretentious automotive designIt’s not exactly king of the crossovers, but the Subaru Forester e-Boxer is reliable, practical and great for keeping a low profile

By Jonathan Bell

-

Sotheby’s is auctioning a rare Frank Lloyd Wright lamp – and it could fetch $5 million

Sotheby’s is auctioning a rare Frank Lloyd Wright lamp – and it could fetch $5 millionThe architect's ‘Double-Pedestal’ lamp, which was designed for the Dana House in 1903, is hitting the auction block 13 May at Sotheby's.

By Anna Solomon

-

Architecture, sculpture and materials: female Lithuanian artists are celebrated in Nîmes

Architecture, sculpture and materials: female Lithuanian artists are celebrated in NîmesThe Carré d'Art in Nîmes, France, spotlights the work of Aleksandra Kasuba and Marija Olšauskaitė, as part of a nationwide celebration of Lithuanian culture

By Will Jennings

-

‘Who has not dreamed of seeing what the eye cannot grasp?’: Rencontres d’Arles comes to the south of France

‘Who has not dreamed of seeing what the eye cannot grasp?’: Rencontres d’Arles comes to the south of FranceLes Rencontres d’Arles 2024 presents over 40 exhibitions and nearly 200 artists, and includes the latest iteration of the BMW Art Makers programme

By Sophie Gladstone

-

Van Gogh Foundation celebrates ten years with a shape-shifting drone display and The Starry Night

Van Gogh Foundation celebrates ten years with a shape-shifting drone display and The Starry NightThe Van Gogh Foundation presents ‘Van Gogh and the Stars’, anchored by La Nuit Etoilée, which explores representations of the night sky, and the 19th-century fascination with the cosmos

By Amy Serafin

-

Marisa Merz’s unseen works at LaM, Lille, have a uniquely feminine spirit

Marisa Merz’s unseen works at LaM, Lille, have a uniquely feminine spiritMarisa Merz’s retrospective at LaM, Lille, is a rare showcase of her work, pursuing life’s most fragile, transient details

By Finn Blythe

-

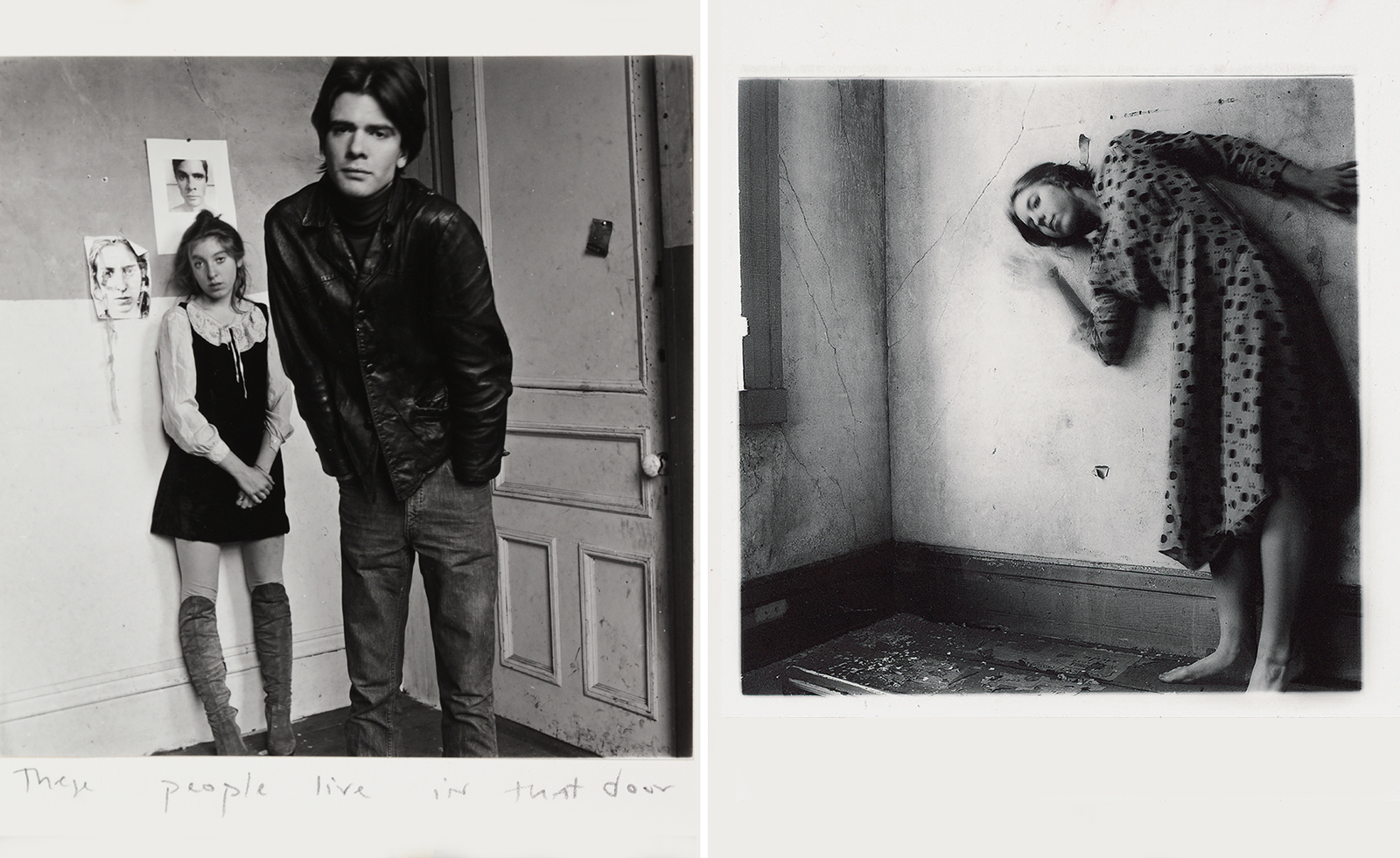

Step into Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron's dreamy photographs in London

Step into Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron's dreamy photographs in London'Portraits to Dream In' is currently on show at London's National Portrait Gallery

By Katie Tobin

-

Damien Hirst takes over Château La Coste

Damien Hirst takes over Château La CosteDamien Hirst’s ‘The Light That Shines’ at Château La Coste includes new and existing work, and takes over the entire 500-acre estate in Provence

By Hannah Silver

-

Tia-Thuy Nguyen encases Chateau La Coste oak tree in tonne of stainless steel strips

Tia-Thuy Nguyen encases Chateau La Coste oak tree in tonne of stainless steel stripsTia-Thuy Nguyen’s ‘Flower of Life’ lives in the grounds of sculpture park and organic winery Château La Coste in France

By Harriet Quick

-

Paris art exhibitions: a guide to exhibitions this weekend

Paris art exhibitions: a guide to exhibitions this weekendAs Emily in Paris fever puts the city of love at the centre of the cultural map, stay-up-to-date with our guide to the best Paris art exhibitions

By Harriet Lloyd-Smith