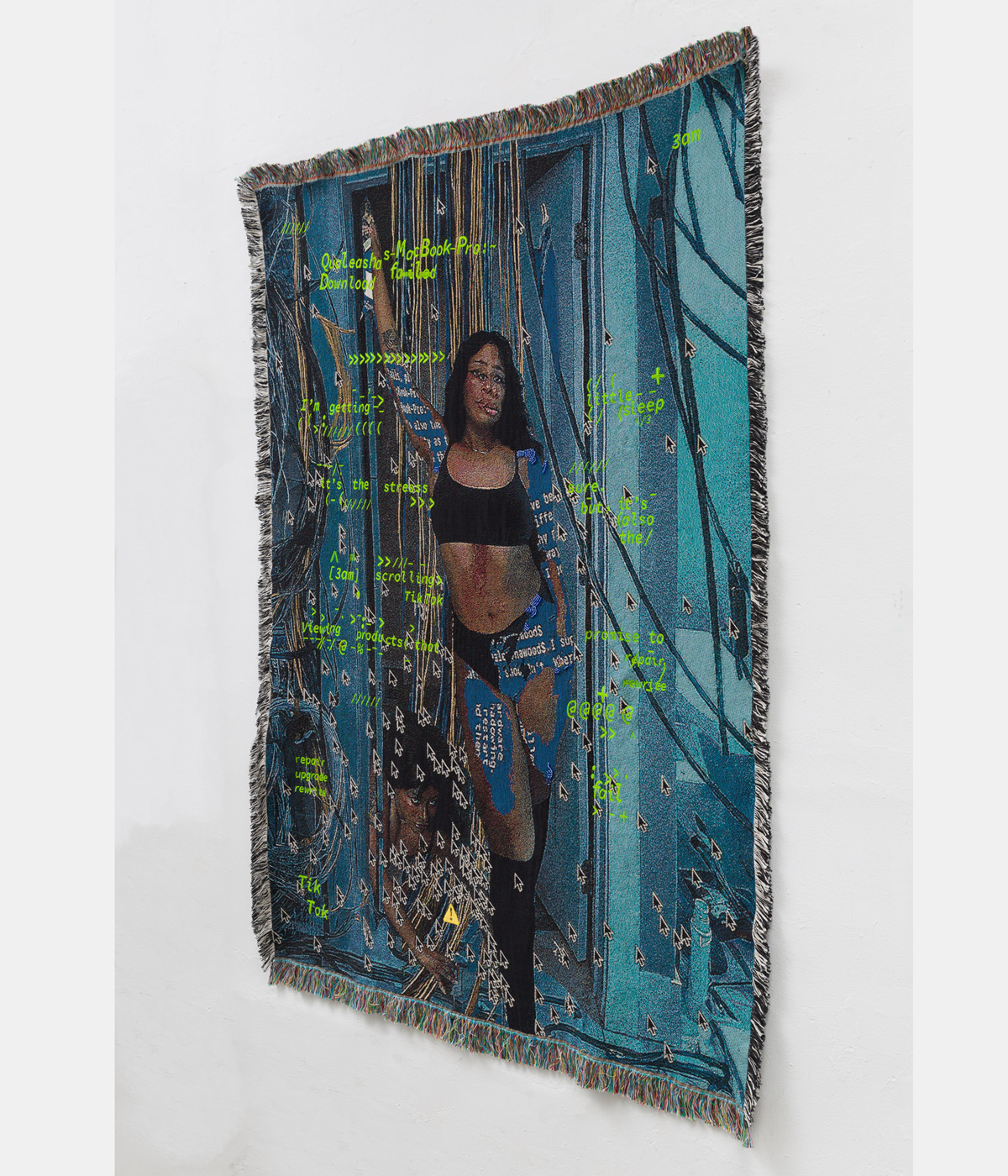

Artist Qualeasha Wood explores the digital glitch to weave stories of the Black female experience

In ‘Malware’, her new London exhibition at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, the American artist’s tapestries, tuftings and videos delve into the world of internet malfunction

What is a glitch? The consequence of an unstable system, glitches expose a vulnerability to threats, but they also open up the possibility of change. It’s a duality that fascinates the Philadelphia-based artist Qualeasha Wood, who jumps into the black hole of internet malfunctions in a new exhibition, ‘Malware’, at London’s Pippy Houldsworth Gallery.

In a series of tapestries, tuftings and videos, Wood marries contemporary digital culture with traditional crafts. In her hands, a digital pixel becomes a single stitch. In video works, she creates glitches by compressing text file data. ‘In this quest for something real, we produce a lot of fake images,’ says Wood. ‘For me, something that feels most natural is something that is decomposing, that’s not perfect or hiding anything. It’s about bringing all those things to the forefront.’

As well as embodying the physical glitch, Wood pulls back the curtain on web platforms themselves, introducing strings of code across her images. ‘Working with coding, and with datamoshing [a video technique with a purposely glitchy effect] in particular, has allowed the works to open up a little more, and they become less about my physical body and its appearance and more about what it’s doing in a space.’

(but i live in a hologram with you), 2025, by Qualeasha Wood

By inserting herself into the image, Wood considers the disruption done to established systems through ‘glitches’, whether from a virus or by the Black female body. The body is ripe for both exploitation and resistance, considered particularly in her webcam self-portraits.

‘I believe social media is akin to a cult or religion, and a lot of my early work was heavily influenced by religion for this reason’

Qualeasha Wood

Wood traces this preoccupation back to her studies at the Rhode Island School of Design, from where she graduated in 2019 with a major in printmaking. Here she found herself falling down a social media rabbit hole. ‘I was constantly speaking about my experience as a Black woman, and there was a lot of resistance. While I was there, navigating this academic career and then the social life, I found I could go online, have a conversation, and have that conversation follow me. The more I engage in these conversations, the more they appear in my work.’

These dialogues led to her making her first image for a tapestry, Cult Following. ‘I believe social media is akin to a cult or religion, and a lot of my early work was heavily influenced by religion for this reason. This idea of having a following seemed to be like being exalted and scapegoated at the same time, feelings I was navigating at the time as I was one of a maximum of 40 Black students on campus.’

Qualeasha Wood, chopped n screwed, 2025

This duality inherent in the digital space, and the capacity it affords for both freedom of expression and hate speech, was crystalised for Wood following her experiences being doxed, something that happened to her twice. The first time, Wood hadn’t yet begun creating her tapestries, and she considered weaving her own image through them as a way of controlling the narrative. But rather than seeing the digital and traditional worlds she was weaving together as directly opposed, she says she learned they’re interconnected.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

During childhood, she was surrounded by the tangible results of her great-grandmother and great-aunt’s crocheting habits, their blankets and handmade objects hanging in doorways or on walls. ‘I was drawn to craft and textiles for that familiarity. And it’s the same with computers. I’ll never know what life was like before the internet. It’s shaped everything that my generation is experiencing, including our pervasive relationship with technology. I found that they went together in terms of systems and rules, and there are moments for exploitation and play within that.’

Wood creates her artworks on a computerised loom, which reads a file and creates a replica of an image. It was inspired by the first tapestry she received, a gift from her grandmother and aunt, which depicted her brother and cousins as babies. ‘That was the first time I realised an image could be woven and that it didn’t have to be stylistic. These were scanned images that my aunt had slapped into some collage maker and thrown onto a website. I think the immediate access of that was really important for me, and the fact that this craft object was not performing in the way that we usually see tapestries in museums was interesting.’

Qualeasha Wood, Camisado, 2025

The most time-consuming part of the creation process is looking through the screenshots on her phone, of which she estimates there are around 30,000-40,000. Choosing which to recreate is instinctive, while weaving the works themselves is the least labour-intensive component. It takes a few weeks, she says, where ‘I release it from my control, and I’m praying that I get my way. It’s literally almost always a surprise.’

‘The tapestries have always been a double-edged sword. I want to be in control of how my body is perceived. But I’m also hyper-aware of the voyeuristic gaze’

Qualeasha Wood

Wood calls herself an avid consumer, typically engaging in around 14 hours of screen time a day. ‘I need my works to be quick, especially if I’m making work about the internet. Something that happened last month is already so old, and I think the work dates itself in that way.’

Working in pixels celebrates an aesthetic beyond the parameters of traditional beauty. ‘I’m not interested in looking pretty and posing. The tapestries, especially, have always been a double-edged sword. I want to be in control of how my body is perceived, so I’m cutting out the middle man and displaying myself in this way. But I’m also hyper-aware of the voyeuristic gaze that still benefits from that. The glitch becomes a marker of vulnerability, but it also has its own power, denying access to this very feminine, perfect thing. It allows me a lot of space.’

‘Malware’ will be on show until 26 April at Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, Heddon Street, London W1, houldsworth.co.uk

This article appears in the May 2025 issue of Wallpaper*, available in print on newsstands from 3 April, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today

Hannah Silver is the Art, Culture, Watches & Jewellery Editor of Wallpaper*. Since joining in 2019, she has overseen offbeat design trends and in-depth profiles, and written extensively across the worlds of culture and luxury. She enjoys meeting artists and designers, viewing exhibitions and conducting interviews on her frequent travels.

-

Fancy a matcha-beer cocktail? Visit this dashing new LA restaurant

Fancy a matcha-beer cocktail? Visit this dashing new LA restaurantCafé 2001 channels the spirit of an American diner with the flow of a European bistro and the artistry of Japanese cuisine

By Carole Dixon

-

Los Angeles businesses regroup after the 2025 fires

Los Angeles businesses regroup after the 2025 firesIn the third instalment of our Rebuilding LA series, we zoom in on Los Angeles businesses and the architecture and social fabric around them within the impacted Los Angeles neighbourhoods

By Mimi Zeiger

-

New book 'I-IN' brings together Japanese heritage and minimalist architecture at its finest

New book 'I-IN' brings together Japanese heritage and minimalist architecture at its finestJapanese architecture studio I-IN flaunts its expert command of 21st-century minimalism in a new book by Frame Publishers

By Ellie Stathaki

-

The UK AIDS Memorial Quilt will be shown at Tate Modern

The UK AIDS Memorial Quilt will be shown at Tate ModernThe 42-panel quilt, which commemorates those affected by HIV and AIDS, will be displayed in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in June 2025

By Anna Solomon

-

‘Humour is foundational’: artist Ella Kruglyanskaya on painting as a ‘highly questionable’ pursuit

‘Humour is foundational’: artist Ella Kruglyanskaya on painting as a ‘highly questionable’ pursuitElla Kruglyanskaya’s exhibition, ‘Shadows’ at Thomas Dane Gallery, is the first in a series of three this year, with openings in Basel and New York to follow

By Hannah Silver

-

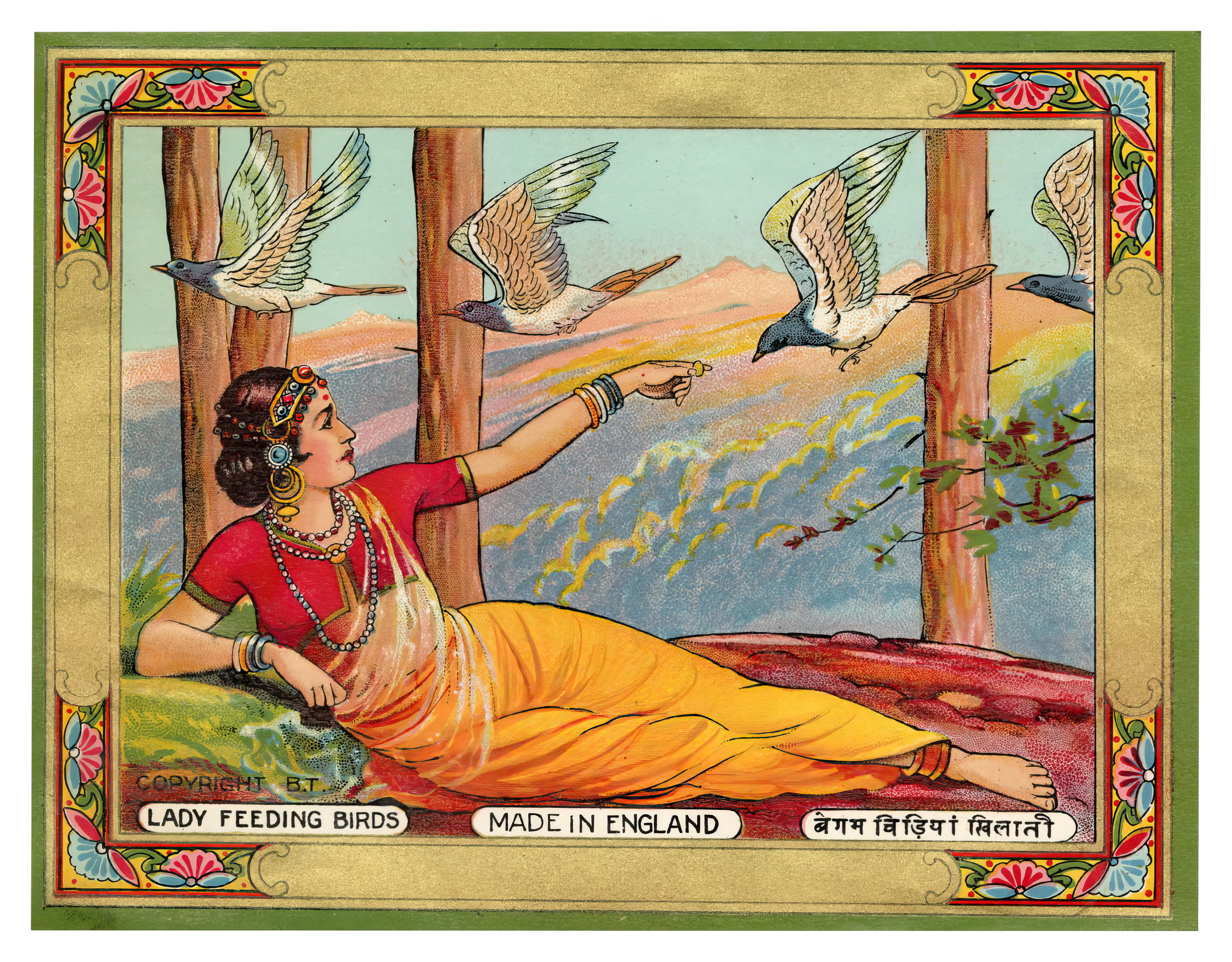

The art of the textile label: how British mill-made cloth sold itself to Indian buyers

The art of the textile label: how British mill-made cloth sold itself to Indian buyersAn exhibition of Indo-British textile labels at the Museum of Art & Photography (MAP) in Bengaluru is a journey through colonial desire and the design of mass persuasion

By Aastha D

-

Ed Atkins confronts death at Tate Britain

Ed Atkins confronts death at Tate BritainIn his new London exhibition, the artist prods at the limits of existence through digital and physical works, including a film starring Toby Jones

By Emily Steer

-

Tom Wesselmann’s 'Up Close' and the anatomy of desire

Tom Wesselmann’s 'Up Close' and the anatomy of desireIn a new exhibition currently on show at Almine Rech in London, Tom Wesselmann challenges the limits of figurative painting

By Sam Moore

-

A major Frida Kahlo exhibition is coming to the Tate Modern next year

A major Frida Kahlo exhibition is coming to the Tate Modern next yearTate’s 2026 programme includes 'Frida: The Making of an Icon', which will trace the professional and personal life of countercultural figurehead Frida Kahlo

By Anna Solomon

-

A portrait of the artist: Sotheby’s puts Grayson Perry in the spotlight

A portrait of the artist: Sotheby’s puts Grayson Perry in the spotlightFor more than a decade, photographer Richard Ansett has made Grayson Perry his muse. Now Sotheby’s is staging a selling exhibition of their work

By Hannah Silver

-

Celia Paul's colony of ghostly apparitions haunts Victoria Miro

Celia Paul's colony of ghostly apparitions haunts Victoria MiroEerie and elegiac new London exhibition ‘Celia Paul: Colony of Ghosts’ is on show at Victoria Miro until 17 April

By Hannah Hutchings-Georgiou