‘Artists are being asked to be vulnerable’: inside the Sharjah Biennial 2025

In the UAE, the 16th Sharjah Biennial, titled ‘To Carry’, seeks to give voices to an international range of artists

The Sharjah Biennial 2025, which recently opened in the UAE (running from February until 15 June), showcases art made in response to world events, from a range of international perspectives. This 16th edition of the biennial, ‘To Carry’, sees five curators seek to give voice and platforms to a truly international group of artists, with a focus on non-Western perspectives.

‘To Carry’ takes its title from a poem that is the curatorial statement. Taking place across 17 venues, the event showcases work by almost 200 participants, spanning artists from Indigenous cultures in Australia and New Zealand to those from Palestine, India, Turkey, Switzerland, Singapore, Afghanistan and beyond.

Sites include Buhais Geological Park, a former seabed flanked by mountains and currently home to Megan Cope’s Kinyingarra Poles, 2025; Sharjah’s 1970s brutalist architecture landmark ‘The Flying Saucer’, a retail site-turned-arts hub that is hosting an installation by Australian art star Daniel Boyd; and a cavernous ex-bank where Julianknxx’s work is displayed. Among other venues are a renovated ice factory on marshland, a disused fruit market, Sharjah Art Museum, and an ex-hospital, now part of the Sharjah Art Foundation that hosts the biennial. The works range hugely in size, theme and media.

The curators are Amal Khalaf, who proposes storytelling, divination and song as rituals for collective learning and resistance; Alia Swastika, who looks at power, poetics and politics; Megan Tamati-Quennell, who focuses on land, impermanence and speculative futures; Natasha Ginwala, who looks at littoral sites and water in Sharjah and beyond; and Zeynep Oz, who looks at societal changes in response to accelerated technological and scientific change. At the opening, each spoke of how rewarding the collaboration has been and this is felt in the theme of the artworks, many of which involve collective work.

Work by Sevil Tunaboylu

The essence of the theme ‘To Carry’ is to carry change in one's work or life, whether that be through choice or circumstance. Speaking to the region where the exhibition takes place, these changes manifest as movement, migration, unrest and the aftermath and rumblings of war. The essence of the curation is empathy but the subjects the biennial deals with are causing the fundamental shifts we are experiencing in the world today.

‘There has been so much intention and [effort] to stay present to what's been going on in the world,’ said co-curator Khalaf. ‘The artists are sharing so many stories that embody this energy of being present and processing; lots of themes, lots of emotions, lots of rage, lots of politics, lots of histories, lots of ruptures run through each of their works. Having them emerge in the biennial all together feels very powerful for me.’

Work by Richard Bell

Featured by co-curator Ginwala is the Singing Wells Project (SWP), a collaboration between Nairobi-based Ketebul Music and London’s Abubila Music, which identifies and preserves recordings of Indigenous East African Music. Shown as a film work, with seats, instruments and headphones to access the archive, SWP’s contribution highlights the fruits of collective work, offering insights into the preservation of a culture that otherwise might not be internationally shared.

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

There is a focus on collectives throughout the biennial, with work from Womanifesto, an international organisation for women artists; UK-based The Voice of Domestic Workers; the Anga collective from Assam; and Bilna’es, a collective whose contributions include a vinyl album, Only Sounds That Tremble Through Us.

Meanwhile, ‘Al Qasimiyah School’ is a moving exhibition of work made by a family fleeing Gaza to Cairo. Parents Dina Mattar and Mohammed Al-Hawarji show paintings, while their son created sculptures of their family’s heads and their daughter made a series of drawings. Accompanied by a film of their journey out of Gaza, this moving group of works gives rare insight into the lived experience of Gazans over the last year.

Reflects co-curator Khalaf, ‘In the process of making the biennial, I was working with artists who are being asked to be vulnerable, to share very difficult things, or to bring people into that process; artists that are going through a lot of things. I had lots of artists that have been displaced, have lost family members, and this was happening to my family, just a few months ago in Lebanon.’

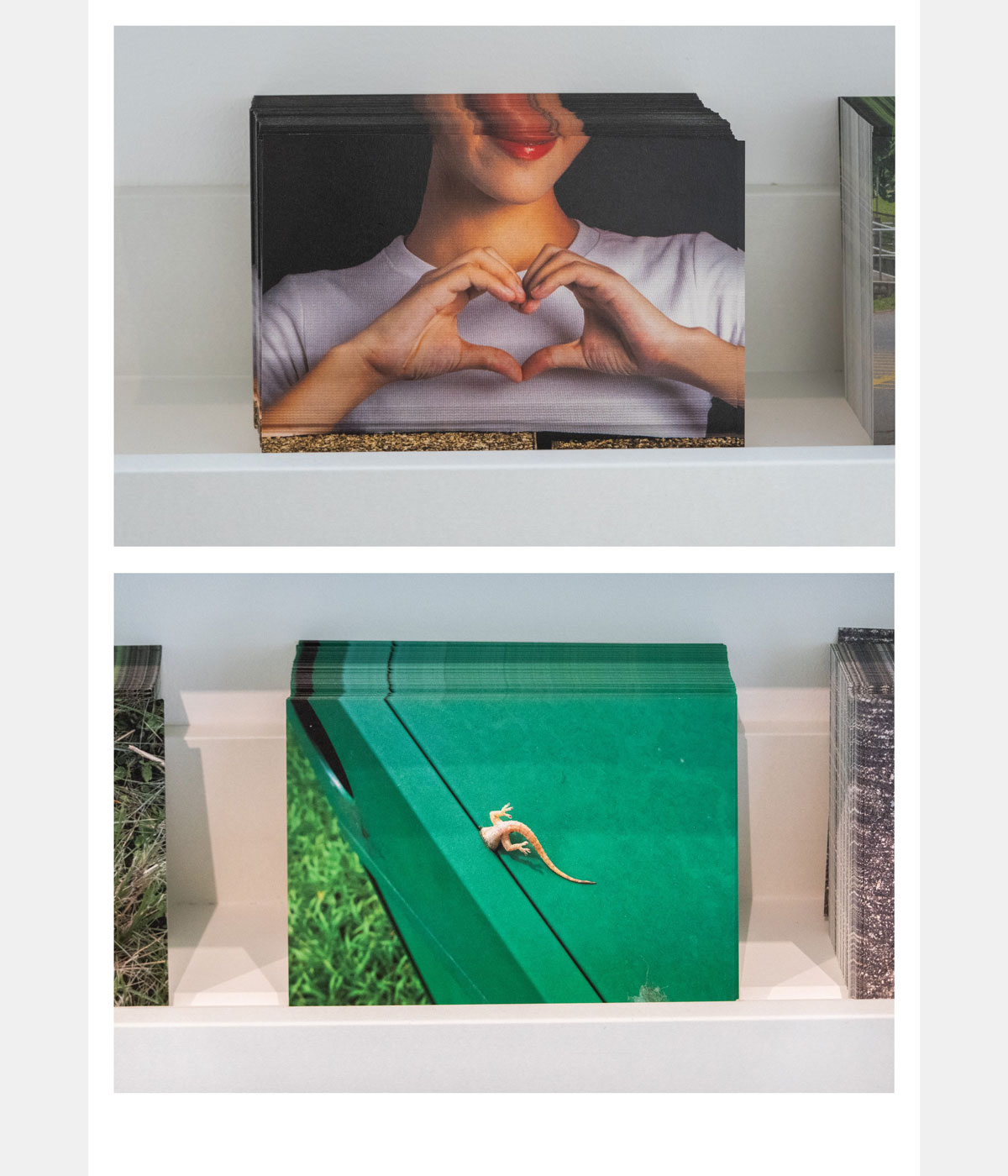

Work by Heman Chong

Themes of grief and mourning are very present in the biennial. Arthur Jafa’s LOML, 2022, a sombre abstract film dedicated to his late friend, the musician, writer and critic Greg Tate.

There is also an embrace of memory. Perimeter Walk, 2013-24, by Heman Chong, is a series of postcards through which he shares his explorations of neglected parts of the coast of Singapore. In reaction to the country’s strict laws, Chong shows us vistas, fragments and found objects, offering up a different view than that of popular imagination. Sharjah Artist Prize winner Aziz Hazara’s I Love Bagram (ILB), 2025, documents a post-war Afghanistan with a focus on the detritus left behind that may or may not be repurposed or reused.

The biennial also brings certain practices to our attention, such as that of Kenyan sculptor Morris Folt, whose modern hand-carved African sculpture captures scenes from everyday life. Folt’s work is shown with that by Indigenous Australian artist Brian Martin, and Alia Farid’s beautiful film Chibayish, 2023, which documents residents of the southern marshlands of Iraq. Farid shows large-scale resin photographic works, printed with images of her Kuwaiti and Puerto-Rican grandmothers that seek to invoke protection

Work by Aluaiy Kaumakan

Concepts of care and preservation bring in works that deal with climate and extraction. Stephanie Comilang’s stunning film installation sees the artist project her work, Search for Life II, 2025, about the history of the pearl trade and the impact of mass production today, onto a screen made from strings of pearl. Separated by a scaffolding platform is another screen playing pearl-related social media posts, fake pearl scams, and content highlighting the warped nature of what is essentially a farming industry.

Adelita Husni-Bey’s Like a Flood, 2025, is a standout work, a film in three parts dealing with failing water infrastructures, colonialism and climate change, effectively making its point in the setting of a life-sized dystopian building site.

The open nature of the message of the Sharjah Biennial 2025 is intended to sit in opposition to negative forces in a strong but gentle way, offering alternative ideas of paths forward. At times, the five threads that run through the exhibition seem disparate and then they reconvene, the message of catharsis and solidarity remaining inspiring.

The 16th Sharjah Biennial runs until 15 June 2025

Amah-Rose Abrams is a British writer, editor and broadcaster covering arts and culture based in London. In her decade plus career she has covered and broken arts stories all over the world and has interviewed artists including Marina Abramovic, Nan Goldin, Ai Weiwei, Lubaina Himid and Herzog & de Meuron. She has also worked in content strategy and production.

-

Glastonbury’s Terminal 1 is back: ‘Be prepared to be deeply moved and then completely uplifted’

Glastonbury’s Terminal 1 is back: ‘Be prepared to be deeply moved and then completely uplifted’Terminal 1 is an immersive, experiential space designed to deliver a vital message on immigration rights at Glastonbury 2025

-

At Glastonbury’s reinvented Shangri-La, everything must grow

At Glastonbury’s reinvented Shangri-La, everything must growWith a new theme for 2025, Glastonbury’s Shangri-La is embracing nature, community and possibility; Lisa Wright is our field agent

-

Paul Smith brings the Swinging Sixties to Sadler’s Wells in ‘Quadrophenia, A Mod Ballet’

Paul Smith brings the Swinging Sixties to Sadler’s Wells in ‘Quadrophenia, A Mod Ballet’In any imagining of Pete Townshend’s ‘rock opera’ – a chronicle steeped in the mythology of the 1960s – the suits need to be razor-sharp. ‘Quadrophenia, A Mod Ballet’ enlisted Paul Smith for the task

-

How the Sharjah Biennial 15 is subverting art world legacies

How the Sharjah Biennial 15 is subverting art world legaciesBuilt on the vision of late curator Okwui Enwezor, the Sharjah Biennial 15: ‘Thinking Historically in the Present’ offers a critical reframing of postcolonial narratives through major new commissions

-

Gallery Collectional launches during Dubai Design Week

Gallery Collectional launches during Dubai Design WeekThe new gallery in Dubai’s Eden House opens with inaugural exhibition ‘The Shape of Things to Come’ and unveils new mirrors by Sabine Marcelis

-

Sharjah Biennial 14 is raising the emirate’s cultural cachet

Sharjah Biennial 14 is raising the emirate’s cultural cachetThemed ‘Leaving the Echo Chamber’, the 14th edition of the Sharjah Art Foundation-driven initiative presents over 60 major new commissions

-

Unearthing the cultural stories and emotional forces behind Emirati design

Unearthing the cultural stories and emotional forces behind Emirati design -

Middle East revealed: W* explores Dubai's growing design scene

Middle East revealed: W* explores Dubai's growing design scene -

Photo finish: Dubai hosts inaugural photography exhibition

Photo finish: Dubai hosts inaugural photography exhibition -

The future was: Wallpaper* explores Art Dubai 2016

The future was: Wallpaper* explores Art Dubai 2016 -

A new conversation: Stéphane Custot on Dubai's emerging art markets

A new conversation: Stéphane Custot on Dubai's emerging art markets