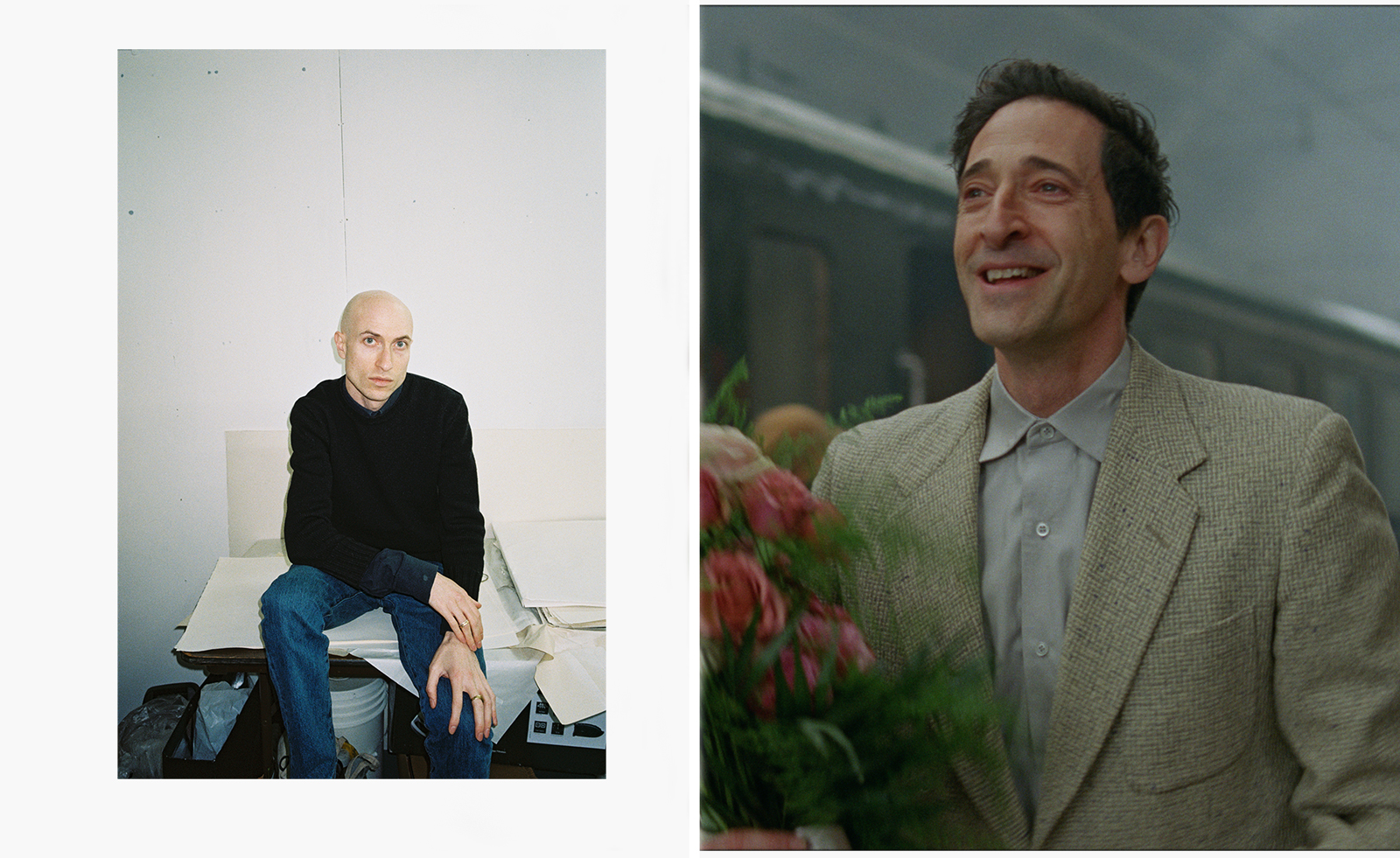

Meet Daniel Blumberg, the British indie rock veteran who created The Brutalist’s score

Oscar and BAFTA-winning Blumberg has created an epic score for Brady Corbet’s film The Brutalist.

‘Monumental’ they’re calling it. They being film critics, it being The Brutalist and the word being a, well, monumentally apposite adjective for Brady Corbet’s 215-minute epic about a Holocaust survivor Hungarian architect at the heart of the post-war American century. So much so that the descriptor appears, in giant lettering, on the official poster for this VistaVision spectacular, attributed to reviews of The Brutalist in no fewer than five UK and US publications. That doesn’t even include the headline from Architectural Record: ‘To Make The Brutalist Monumental, the Filmmakers Approached Cinema as Architecture’.

How, then, to create a score to match that scale, those heights, Corbet’s ambitions and the awards-bait performances of stars Adrien Brody, Felicity Jones and Guy Pearce? For musician and composer Daniel Blumberg – a young veteran of British indie rock bands (Cajun Dance Party, Yuck) and of the avant-garde music scene centred on Cafe Oto in Dalston, east London – it’s very much job done. As The Brutalist’s pre-titles opening scene looms into view, with Brody’s László Tóth, a disorientated, damaged refugee from the war in Europe, arriving in New York harbour, Blumberg’s alt-classical music swells up with a mighty, sonorous blast of brass. This is ‘Overture (Ship)’, and it’s as breathtaking and unbalancing as Corbet’s shot of an upside-down Statue of Liberty.

Still from The Brutalist

Thereafter, Blumberg, in simpatico concert with Corbet, takes us on a creative journey as far-reaching and bracing as László’s. It’s an aural odyssey that spans the decades, from the 1940s to the 1980s; the Atlantic, from industrial Pennsylvania to the marble quarries of Carrera in Italy; and the genres, from bepop to jazz to synthpop via Blumberg’s personal, DIY, self-taught, very east London take on musique concrète.

A giant undertaking, for sure – one for which Blumberg has been BAFTA-nominated, alongside multiple eight other nominations for the film, news that broke midway through our interview (‘Why are my family texting me?’ he wondered, nonplussed, as his phone started buzzing; since then, his Oscar nomination has also rolled in). But for the Londoner, it was simply a case of following his filmmaker peer’s lead.

‘From when I first read the script, it was the most important project I've ever done – for many reasons. The script was so special, and Brady's a very close friend of mine,’ says the 34-year-old of the 36-year-old from Arizona. He first met the American during the making of his first feature, 2015’s The Childhood of a Leader, and then scored The World to Come, the 2020 film by Corbet’s filmmaker wife, Mona Fastvold. So Blumberg knew better than most the seven-year saga of The Brutalist’s stop-start journey from brain to page to screen. ‘The idea of helping him make his work was important. And making something and not f*cking it up was the main ambition.’

Blumberg wrote his first piece of The Brutalist score, a four-minute section, in 2020. Corbet wanted to film a budget-raising ‘teaser’ segment in the Covid-emptied streets of Venice that would ultimately form the epilogue of his film.

Daniel Blumberg on set

‘That piece ended up being the cue called ‘Construction’ on the film,’ says Blumberg over coffee near his north London flat. ‘It was my first instinct what the sonic world of the film could be. I started thinking about architecture, how it could translate to music, and reading about Bauhaus.

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox.

‘The piano was an obvious choice, in terms of it being this vast acoustic [instrument],’ he continues. ‘But I wedged things into the strings. Then, when the hammers hit it, you make it into a percussive instrument.’ It’s a technique favoured by John Cage, ‘who would put screws and stuff in… then you can make these “ding dong” sounds’.

And he was off… kind of. Covid and financial challenges meant it would be another three years before production finally began in budget-friendly Hungary. Locations around Budapest stood in for the Pennsylvanian countryside in which Pearce’s rapacious industrialist Harrison Lee Van Buren commissions Tóth to build a hilltop community centre, a – yes – monument to his late mother. Blumberg embedded himself onset, and bedded down in Corbet’s apartment in Budapest, ‘in a tiny room where I had a keyboard and my bed’.

The first day of production was a pivotal scene in a jazz club. Corbet, as exacting in his vision as the uncompromising Tóth, wanted to shoot the scene to a live jazz band – playing a jazz piece freshly composed by Blumberg.

‘They do the filming schedule quite suddenly, so there was a challenge to get the right musicians, and I had a list of who I thought would work for that,’ he says of jazz players he flew in from Paris, Marseille and Berlin. ‘But the scariest thing was that we wanted László to have this defining moment in his life. Where he hears this music and never forgets it. Then you hear it in its totality towards the end of the film, when the construction [of Tóth’s building] starts. It's like he retains it in his brain. ‘So [writing] that theme was scary, because you're imprinting an idea for a three-and-a-half hour film – and I was hoping that it would be good enough to maintain that from such an early stage of the film.’

To score the scenes shot at the Carrera marble quarries, Blumberg had to think more tangentially. He knew he wanted a site-specific recording of saxophonist Evan Parker, the 80-year-old, Kent-based maestro of free improvisation. But Parker, who was on tour, couldn’t make it to Italy. So Blumberg and his girlfriend, a conceptual artist based in Barcelona, visited the location armed with mics and a gun.

A gun? ‘Yeah! You fire a gun and put the recording at the highest sample rate, so you're getting as much information as possible. You record the gunshot, and then the response of the valley on that gunshot. I took it back to London and made an algorithm of it. Then you tell the program that that's the source, it removes the gunshot and makes this kind of reverb based on the echo of the gunshot. Then I applied that to Evan’s saxophone.’

Still from The Brutalist

Blumberg spent 18 solid months composing a score that would end up comprising 32 pieces of music running to 81 minutes. I ask him: given his friend’s messianic mission to make his movie – and bring it in on a frankly astonishing sub-$10 million budget, without curtailing his vision – was it incumbent on the composer to match the director’s rigour and vigour?

‘Definitely,’ says Blumberg, a man with a gentle nature and a spirit of steel. ‘I wanted to get to the end of the process and know I did everything possible to make this score the best it could be. Even if that algorithm, that reverb – the impulse response, it's called – hadn't worked, at least I’d tried it.’

Equally, he and Corbet have something akin to a pact. ‘I started young with music and he started very young with acting,’ Blumberg, who formed Cajun Dance Party as a schoolboy, says of the adolescent star of teen drama Thirteen (2003). ‘And we're people who said no to compromise. That’s something we have an affinity on. So it felt like an amalgamation of this relationship and all this [creative] stuff. And weirdly as well, kind of embarrassingly, this is what the film's about. It was,’ he concludes with a smile, ‘like method scoring.’

Next up: Daniel Blumberg is working on Mona Fastvold's new film. It's about the Shakers, the millenarian Christian sect, and their 18th-century immigration to America from Manchester – and it's a musical. And we thought The Brutalist was a bold undertaking for the composer...

The Brutalist is in UK cinemas from 24 January

Read: Architecture and the new world: The Brutalist reframes the American dream

London-based Scot, the writer Craig McLean is consultant editor at The Face and contributes to The Daily Telegraph, Esquire, The Observer Magazine and the London Evening Standard, among other titles. He was ghostwriter for Phil Collins' bestselling memoir Not Dead Yet.

-

Warp Records announces its first event in over a decade at the Barbican

Warp Records announces its first event in over a decade at the Barbican‘A Warp Happening,' landing 14 June, is guaranteed to be an epic day out

By Tianna Williams

-

Cure your ‘beauty burnout’ with Kindred Black’s artisanal glassware

Cure your ‘beauty burnout’ with Kindred Black’s artisanal glasswareDoes a cure for ‘beauty burnout’ lie in bespoke design? The founders of Kindred Black think so. Here, they talk Wallpaper* through the brand’s latest made-to-order venture

By India Birgitta Jarvis

-

The UK AIDS Memorial Quilt will be shown at Tate Modern

The UK AIDS Memorial Quilt will be shown at Tate ModernThe 42-panel quilt, which commemorates those affected by HIV and AIDS, will be displayed in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in June 2025

By Anna Solomon

-

Unlike the gloriously grotesque imagery in his films, Yorgos Lanthimos’ photographs are quietly beautiful

Unlike the gloriously grotesque imagery in his films, Yorgos Lanthimos’ photographs are quietly beautifulAn exhibition at Webber Gallery in Los Angeles presents Yorgos Lanthimos’ photography

By Katie Tobin

-

‘Life is strange and life is funny’: a new film goes inside the world of Martin Parr

‘Life is strange and life is funny’: a new film goes inside the world of Martin Parr‘I Am Martin Parr’, directed by Lee Shulman, makes the much-loved photographer the subject

By Hannah Silver

-

The Chemical Brothers’ Tom Rowlands on creating an electronic score for historical drama, Mussolini

The Chemical Brothers’ Tom Rowlands on creating an electronic score for historical drama, MussoliniTom Rowlands has composed ‘The Way Violence Should Be’ for Sky’s eight-part, Italian-language Mussolini: Son of the Century

By Craig McLean

-

Remembering David Lynch (1946-2025), filmmaking master and creative dark horse

Remembering David Lynch (1946-2025), filmmaking master and creative dark horseDavid Lynch has died aged 78. Craig McLean pays tribute, recalling the cult filmmaker, his works, musings and myriad interests, from music-making to coffee entrepreneurship

By Craig McLean

-

Architecture and the new world: The Brutalist reframes the American dream

Architecture and the new world: The Brutalist reframes the American dreamBrady Corbet’s third feature film, The Brutalist, demonstrates how violence is a building block for ideology

By Billie Walker

-

‘It creates mental horrors’ – why The Thing game remains so chilling

‘It creates mental horrors’ – why The Thing game remains so chillingWallpaper* speaks to two of the developers behind 2002’s cult classic The Thing video game, who hope the release of a remastered version can terrify a new generation of gamers

By Thomas Hobbs

-

Wu Tsang reinterprets Carmen's story in Barcelona

Wu Tsang reinterprets Carmen's story in BarcelonaWu Tsang rethinks Carmen with an opera-theatre hybrid show and a film installation, recently premiered at MACBA in Barcelona (until 3 November)

By Emily Steer

-

Miu Miu’s Women’s Tales film series comes to life for Art Basel Paris

Miu Miu’s Women’s Tales film series comes to life for Art Basel ParisIn ‘Tales & Tellers’, interdisciplinary artist Goshka Macuga brings Miu Miu’s Women’s Tales film series for Art Basel Paris to life for the public programme

By Amah-Rose Abrams